OXRAPX Cover Final.Eps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Historic Oxford Castle Perimeter Walk

Historic Oxford Castle 10 Plan (1878 Ordnance N Survey) and view of Perimeter Walk 9 11 12 the coal wharf from Bulwarks Lane, 7 under what is now Beat the bounds of Oxford Castle Nuffield College 8 1 7 2 4 3 6 5 Our new book Excavations at Oxford Castle 1999-2009 A number of the features described on our tour can be is available Oxford Castle & Prison recognised on Loggan’s 1675 map of Oxford. Note that gift shop and Oxbow: Loggan, like many early cartographers, drew his map https://www.oxbowbooks.com/ from the north, meaning it is upside-down compared to To find out more about Oxford modern maps. Archaeology and our current projects, visit our website or find us on Facebook, Twitter and Sketchfab: J.B. Malchair’s view of the motte in 1784 http://oxfordarchaeology.com @oatweet “There is much more to Oxford Castle than the mound and shops you see today. Take my tour to facebook.com/oxfordarchaeology ‘beats the bounds’ of this historic site sketchfab.com/oxford_archaeology and explore the outer limits of the castle, and see where excavations To see inside the medieval castle and later prison visit have given insights into the Oxford Castle & Prison: complex history of this site, that https://www.oxfordcastleandprison.co.uk/ has fascinated me for longer than I care to mention!” Julian Munby View towards the castle from the junction of New Road, 1911 2 Head of Buildings Archaeology Oxford Archaeology Castle Mill Stream Start at Oxford Castle & Prison. 1 8 The old Court House that looks like a N 1 Oxford Castle & Prison The castle mound (motte) and the ditch and Castle West Gate castle is near the site of the Shire Hall in the defences are the remains of the ‘motte and 2 New Road (west) king’s hall of the castle, where the justices bailey’ castle built in 1071 by Robert d’Oilly, 3 West Barbican met. -

Glaven Historian

the GLAVEN HISTORIAN No 16 2018 Editorial 2 Diana Cooke, John Darby: Land Surveyor in East Anglia in the late Sixteenth 3 Jonathan Hooton Century Nichola Harrison Adrian Marsden Seventeenth Century Tokens at Cley 11 John Wright North Norfolk from the Sea: Marine Charts before 1700 23 Jonathan Hooton William Allen: Weybourne ship owner 45 Serica East The Billyboy Ketch Bluejacket 54 Eric Hotblack The Charities of Christopher Ringer 57 Contributors 60 2 The Glaven Historian No.16 Editorial his issue of the Glaven Historian contains eight haven; Jonathan Hooton looks at the career of William papers and again demonstrates the wide range of Allen, a shipowner from Weybourne in the 19th cen- Tresearch undertaken by members of the Society tury, while Serica East has pulled together some his- and others. toric photographs of the Billyboy ketch Bluejacket, one In three linked articles, Diana Cooke, Jonathan of the last vessels to trade out of Blakeney harbour. Hooton and Nichola Harrison look at the work of John Lastly, Eric Hotblack looks at the charities established Darby, the pioneering Elizabethan land surveyor who by Christopher Ringer, who died in 1678, in several drew the 1586 map of Blakeney harbour, including parishes in the area. a discussion of how accurate his map was and an The next issue of Glaven Historian is planned for examination of the other maps produced by Darby. 2020. If anyone is considering contributing an article, Adrian Marsden discusses the Cley tradesmen who is- please contact the joint editor, Roger Bland sued tokens in the 1650s and 1660s, part of a larger ([email protected]). -

Agenda Item 2

Agenda Item 2 To: Licensing & Gambling Acts Casework Sub-Committee Date: 26 May 2015 Item No: 2 Report of: Head of Environmental Development Title of Report: Holly Bush Property Ltd – Application for a New Premises Licence: The Holly Bush Inn, 106 Bridge Street, Oxford, OX2 0BD Application Ref: 15/01192/PREM Summary and Recommendations Purpose of report: To inform the determination of Holly Bush Property Ltd’s application for a New Premises Licence for The Holly Bush Inn, 106 Bridge Street, Oxford, OX2 0BD Report Approved by: Legal: Daniel Smith Policy Framework: Statement of Licensing Policy Recommendation(s): Committee is requested to determine Holly Bush Property Ltd’s application taking into account the details in this report and any representations made at this Sub- Committee meeting. Additional Papers: Appendix One: Application for a New Premises Licence Appendix Two: Representations from Responsible Authorities Appendix Three: Agreement of Applicant to Licensing Authority & Thames Valley Police proposed hours Appendix Four: Agreement of Applicant to Licensing Authority & Thames Valley Police proposed conditions Appendix Five: Representations from Interested Parties Appendix Six: Location Map 31 1 Introduction 1. This report is made to the Licensing & Gambling Acts Casework Sub- Committee so it may determine in accordance with its powers and the Licensing Act 2003 whether to grant a New Premises Licence to Holly Bush Property Ltd. Application Summary 2. An application for a New Premises Licence has been submitted by Holly Bush Property -

9780521650601 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 0521650607 - Pragmatic Utopias: Ideals and Communities, 1200-1630 Edited by Rosemary Horrox and Sarah Rees Jones Index More information Index Aberdeen, Baxter,Richard, Abingdon,Edmund of,archbp of Canterbury, Bayly,Thomas, , Beauchamp,Richard,earl of Warwick, – Acthorp,Margaret of, Beaufort,Henry,bp of Winchester, adultery, –, Beaufort,Margaret,countess of Richmond, Aelred, , , , , , Aix en Provence, Beauvale Priory, Alexander III,pope, , Beckwith,William, Alexander IV,pope, Bedford,duke of, see John,duke of Bedford Alexander V,pope, beggars, –, , Allen,Robert, , Bell,John,bp of Worcester, All Souls College,Oxford, Belsham,John, , almshouses, , , , –, , –, Benedictines, , , , , –, , , , , , –, , – Americas, , Bereford,William, , anchoresses, , – Bergersh,Maud, Ancrene Riwle, Bernard,Richard, –, Ancrene Wisse, –, Bernwood Forest, Anglesey Priory, Besan¸con, Antwerp, , Beverley,Yorks, , , , apostasy, , , – Bicardike,John, appropriations, –, , , , Bildeston,Suff, , –, , Arthington,Henry, Bingham,William, – Asceles,Simon de, Black Death, , attorneys, – Blackwoode,Robert, – Augustinians, , , , , , Bohemia, Aumale,William of,earl of Yorkshire, Bonde,Thomas, , , –, Austria, , , , Boniface VIII,pope, Avignon, Botreaux,Margaret, –, , Aylmer,John,bp of London, Bradwardine,Thomas, Aymon,P`eire, , , , –, Brandesby,John, Bray,Reynold, Bainbridge,Christopher,archbp of York, Brinton,Thomas,bp of Rochester, Bristol, Balliol College,Oxford, , , , , , Brokley,John, Broomhall -

Houses of the Oxford Region

Houses of the Oxford R egion Each article in this new series will consist if a brief description, a plan or plans and at least one plate. While tM series is not restricttd to ' vernacular architecture ' jaTTll)us houses such as Blenheim will be excluded. It is hoped to publish two articles one on a town house and one on a country houst-in each number if Oxoniensia. -Editor. I. FISHER ROW, OXFORD By W. A. PAN"IlN FISHER Row consisted of a row of cottages which stood on a long narrow bank or strip of land running from Hythe Bridge on the north to QUaking Bridge and Castle Millon the south; this bank was bounded on the east by the main stream or mill stream and on the west by a back stream, and its purpose was no doubt to divert the stream to feed the Castle Mill at the southern end; it was at first known by the medieval Latin name of wara (meaning a weir or defence), hence the later name '\Tarham Bank. About half-way down the bank is divided into two halves, north and south, by a sluice which is a short distance south of the modern bridge joining the ew Road to Park End Street.' The tenements south of this sluice were acquired by Oseney Abbey at various dates between about 1240 and 1469; after the Dissolution these passed to Christ Church who also acquired the tenements north of the sluice. The Oseney rentals from c. 1277 show that the tenants included such people as fishermen, carpenters and tanners; similarly the Christ Church leases from c. -

Witold Rybczynski HOME 1 7

Intimacy and Privacy C hap t e r Two 1' And yet it is precisely in these Nordic, apparently gloomy surroundings that Stimrnung, the sense of intimacy, was first born. - MARIO PRAZ AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF INTERIOR DECORATION Consid", the room which Albrecht Durer illustrated in his famous engraving St. Jerome in His Study. The great Ren aissance artist followed the convention of his time and showed the early Christian scholar not in a fifth-century setting-nor in Bethlehem, where he really lived- but in a study whose furnishings were typical of Durer's Nuremberg at the begin ning of the sixteenth century. We see an old man bent over his writing in the corner of a room. Light enters through a large leaded-glass window in an arched opening. A low bench stands against the wall under the window. Some tasseled cushions have been placed on it; upholstered seating, in which the cushion was an integral part of the seat, did not appear until a hundred years later. The wooden table is a medieval design-the top is separate from the underframe, and by removing a couple of pegs the whole thing can be easily disassembled when not in use. A back-stool, the precursor of the side chair, is next to the table. The tabletop is bare except for a crucifix, an inkpot, and a writing stand, but personal possessions are in evidence else Albrecht DUrer, St. Jerome in His where. A pair of slippers has been pushed under the bench. 15 Study (1514) ,... Witold Rybczynski HOME 1 7 folios on the workplace, whether it is a writer's room or the cockpit of a The haphazard is not a sign of sloppiness-bookcases have not yet jumbo jet. -

Reading Abbey Revealed Conservation Plan August 2015

Reading Abbey Revealed Conservation Plan August 2015 Rev A First Draft Issue P1 03/08/2015 Rev B Stage D 10/08/2015 Prepared by: Historic Buildings Team, HCC Property Services, Three Minsters House, 76 High Street, Winchester, SO23 8UL On behalf of: Reading Borough Council Civic Offices, Bridge Street, Reading RG1 2LU Conservation Plan – Reading Abbey Revealed Contents Page Historical Timeline ………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.0 Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………… 2 2.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 3.0 Understanding the Heritage 3.1 – Heritage Description ……………………………………………………………………… 5 3.2 – History ……………………………………………………………………………………… 5 3.3 – Local Context ……………………………………………………………………………… 19 3.4 – Wider Heritage Context ………………………………………………………………….. 20 3.5 – Current Management of Heritage ………………………………………………………. 20 4.0 Statement of Significance 4.1 – Evidential Value ………………………………………………………………………….. 21 4.2 – Historical Value …………………………………………………………………………... 21 4.3 – Aesthetic Value …………………………………………………………………………… 21 4.4 – Communal Value …………………………………………………………………………. 22 4.5 - Summary of Significance ………………………………………………………………... 24 5.0 Risks to Heritage and Opportunities 5.1 – Risks ………………………………………………………………………………………. 26 5.2 – Opportunities ……………………………………………………………………………… 36 6.0 Policies 6.1 – Conservation, maintenance and climate change …………………………………….. 38 6.2 – Access and Interpretation ……………………………………………………………….. 39 6.3 – Income Generation ………………………………………………………………………. 40 7.0 Adoption and Review 7.1 – General Approach -

Oxford Walk & Talk

Oxford Walk & Talk Duration: 60-75 “River & Stream” mins Updated by Ros Weatherall & Liz Storrar, February 2013 Oxford was defined by its water courses long before the arrival of its University. This leisurely walk will take you along the Mill Stream Walk, following the stream which powered the city’s mill, returning alongside the modern navigable River Thames. The walk 1. From Bonn Square walk to your right, 50 metres towards New Road. Cross the road at the zebra crossing and walk downhill along Castle Street, with County Hall to your right. 2. Turn right at the Castle Tavern into Paradise Street, and follow it past Paradise Square to your left. Cross the bridge over the stream (the Castle Mill Stream) – see the Norman tower of the Castle to your right - turn immediately left (marked Woodin’s Way) and double back on yourself to walk along the Millstream Path with the stream on your left (passing the Europe Business Assembly building to your right). 3. Walk beside the stream and after crossing it turn right to continue on the path – the stream is now to your right, and housing to your left. Where the housing ends turn left and immediately right to pass through a passage beside the housing signed as 1-14 Abbey Place. This leads you to a car park adjoining what is now a building site, where construction of the extended Westgate Centre will begin at some point in the future. 4. Walk ahead across the car park (with a hoarding to your right) to the main road (Thames Street/Oxpens Road). -

1257738 Ocford Traffic Table X85.Indd

OXFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 – SECTION 14(1) & (5) Notice of Temporary Traffic Order Oxford – Frideswide Square Area Temporary Traffic Restrictions Date of Order: 5 February 2018 Coming into force: 11 February 2018 This Order is being introduced because of kerb-line improvement works which are anticipated to take until 3 March to complete. The effect of the Order is to temporarily impose the following restrictions: One-Way Restriction Road Section of RoadDuration Diversion westbound Park End Street/ Hollybush Row 11/02/18 - Becket Street Frideswide to Becket Street 23/02/18 – Osney Lane Square & Hollybush southboundBecket Street Park End Street 11/02/18 - Row to Osney Lane 23/02/18 eastboundOsney LaneBecket Street to 11/02/18 - Hollybush/Oxpens 23/02/18 Road southboundWorcester Street George Street to 25/02/18 - Hythe Bridge New Road 16/03/18 Street westbound Park End Street New Road to 25/02/18 - – Worcester Frideswide Square 16/03/18 Street & Park End Street eastbound Hythe Bridge Frideswide Square 25/02/18 - Street to Worcester Street 16/03/18 No Left Turn Railway Station Exit onto Frideswide 11/02/18 - Uses of the Square Oxpens Road onto Osney Lane 23/02/18 one-way No Right Turn Rewley Road onto Hythe Bridge Street 25/02/18 - diversion route Upper Fisher Row onto Hythe Bridge Street 16/03/18 Worcester Street onto Hythe Bridge Street George Street Mews onto Worcester Street New Road onto Worcester Street Park End Place onto Park End Street Hollybush Row onto Park End Street Park End Street (Frideswide Square) onto Park End Street/Hollybush Row Appropriate traffic signs will be displayed to indicate when the measures are in force. -

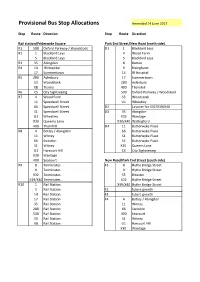

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017 Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Rail station/Frideswide Square Park End Street/New Road (north side) R1 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock D1 1 Blackbird Leys R2 1 Blackbird Leys 4 Wood Farm 5 Blackbird Leys 5 Blackbird Leys R3 35 Abingdon 8 Barton R4 14 JR Hospital 9 Risinghurst 17 Summertown 14 JR Hospital R5 280 Aylesbury 17 Summertown S3 Woodstock 280 Aylesbury X8 Thame 400 Thornhill R6 CS City Sightseeing 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock R7 4 Wood Farm S3 Woodstock 11 Speedwell Street U1 Wheatley 66 Speedwell Street D2 Layover for X32/X39/X40 S1 Speedwell Street D3 35 Abingdon U1 Wheatley X32 Wantage X30 Queems Lane X39/X40 Wallingford 400 Thornhill D4 11 Butterwyke Place R8 4 Botley / Abingdon 66 Butterwyke Place 11 Witney S1 Butterwyke Place 66 Swindon S5 Butterwyke Place S1 Witney X30 Queens Lane U1 Harcourt Hill CS City Sightseeing X30 Wantage 400 Seacourt New Road/Park End Street (south side) R9 8 Terminates F1 8 Hythe Bridge Street 9 Terminates 9 Hythe Bridge Street X32 Terminates S5 Bicester X39/X40 Terminates X32 Hythe Bridge Street R10 1 Rail Station X39/X40 Hythe Bridge Street 5 Rail Station F2 future growth 14 Rail Station F3 future growth 17 Rail Station F4 4 Botley / Abingdon 35 Rail Station 11 Witney 280 Rail Station 66 Swindon 500 Rail Station 400 Seacourt S3 Rail Station S1 Witney X8 Rail Station U1 Harcourt Hill X30 Wantage Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Castle Street/Norfolk Street (west side) Castle Street/Norfolk Street (east side) E1 4 Botley -

Index of Manuscripts

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-44420-0 - The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature Edited by David Wallace Index More information Index of manuscripts Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales Durham Cathedral Library 6680: 195 b.111.32, f. 2: 72n26 c.iv.27: 42, 163n25 Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 32: 477 Edinburgh, National Library of Scotland 140: 461n28 Advocates 1.1.6 (Bannatyne MS): 252 145: 619 Advocates 18.7.21: 361 171: 234 Advocates 19.2.1 (Auchinleck MS): 91, 201: 853 167, 170–1, 308n42, 478, 624, 693, 402: 111 697 Cambridge, Gonville and Caius College Advocates 72.1.37 (Book of the Dean of 669/646: 513n2 Lismore): 254 Cambridge, Magdalene College Pepys 2006: 303n32, 308n42 Geneva, Fondation Martin Bodmer Pepys 2498: 479 Cod. Bodmer 168: 163n25 Cambridge, Trinity College b.14.52: 81n37 Harvard, Houghton Library b.15.18: 337n104 Eng 938: 51 o.3.11: 308n42 Hatfield House o.9.1: 308n42 cp 290: 528 o.9.38 (Glastonbury Miscellany): 326–7, 532 Lincoln Cathedral Library r.3.19: 308n42, 618 91: 509, 697 r.3.20: 59 London, British Library r.3.21: 303n32, 308n42 Additional 16165: 513n2, 526 Cambridge, University Library Additional 17492 (Devonshire MS): 807, Add. 2830: 387, 402–6 808 Add. 3035: 593n16 Additional 22283 (Simeon MS): 91, dd.1.17: 513n2, 515n6, 530 479n61 dd.5.64: 498 Additional 24062: 651 ff.4.42: 186 Additional 24202: 684 ff.6.17: 163n25 Additional 27879 (Percy Folio MS): 692, gg.1.34.2: 303n32 693–4, 702, 704, 708, 710–12, 718 gg.4.31: 513n2, 515n6 Additional 31042: 697 hh.1.5: 403n111 Additional 35287: