Glaven Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Share Report

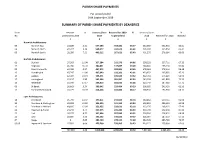

PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS For period ended 30th September 2019 SUMMARY OF PARISH SHARE PAYMENTS BY DEANERIES Dean Amount % Deanery Share Received for 2019 % Deanery Share % No Outstanding 2018 2019 to period end 2018 Received for 2018 received £ £ £ £ £ Norwich Archdeaconry 06 Norwich East 23,500 4.41 557,186 354,184 63.57 532,380 322,654 60.61 04 Norwich North 47,317 9.36 508,577 333,671 65.61 505,697 335,854 66.41 05 Norwich South 28,950 7.21 409,212 267,621 65.40 401,270 276,984 69.03 Norfolk Archdeaconry 01 Blofield 37,303 11.04 327,284 212,276 64.86 338,033 227,711 67.36 11 Depwade 46,736 16.20 280,831 137,847 49.09 288,484 155,218 53.80 02 Great Yarmouth 44,786 9.37 467,972 283,804 60.65 478,063 278,114 58.18 13 Humbleyard 47,747 11.00 437,949 192,301 43.91 433,952 205,085 47.26 14 Loddon 62,404 19.34 335,571 165,520 49.32 322,731 174,229 53.99 15 Lothingland 21,237 3.90 562,194 381,997 67.95 545,102 401,890 73.73 16 Redenhall 55,930 17.17 339,813 183,032 53.86 325,740 187,989 57.71 09 St Benet 36,663 9.24 380,642 229,484 60.29 396,955 243,433 61.33 17 Thetford & Rockland 31,271 10.39 314,266 182,806 58.17 300,933 192,966 64.12 Lynn Archdeaconry 18 Breckland 45,799 11.97 397,811 233,505 58.70 382,462 239,714 62.68 20 Burnham & Walsingham 63,028 15.65 396,393 241,163 60.84 402,850 256,123 63.58 12 Dereham in Mitford 43,605 12.03 353,955 223,631 63.18 362,376 208,125 57.43 21 Heacham & Rising 24,243 6.74 377,375 245,242 64.99 359,790 242,156 67.30 22 Holt 28,275 8.55 327,646 207,089 63.21 330,766 214,952 64.99 23 Lynn 10,805 3.30 330,152 196,022 59.37 326,964 187,510 57.35 07 Repps 0 0.00 383,729 278,123 72.48 382,728 285,790 74.67 03 08 Ingworth & Sparham 27,983 6.66 425,260 239,965 56.43 420,215 258,960 61.63 727,583 9.28 7,913,818 4,789,282 60.52 7,837,491 4,895,456 62.46 01/10/2019 NORWICH DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE LTD DEANERY HISTORY REPORT MONTH September YEAR 2019 SUMMARY PARISH 2017 OUTST. -

River Glaven State of the Environment Report

The River Glaven A State of the Environment Report ©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative ©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence © Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this C reative ©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence Commons Licence Produced by Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service Spring 201 4 i Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service (NBIS) is a Local Record Centre holding information on species, GEODIVERSITY , habitats and protected sites for the county of Norfolk. For more information see our website: www.nbis.org.uk This report is available for download from the NBIS website www.nbis.org.uk Report written by Lizzy Oddy, March 2014. Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank the following people for their help and input into this report: Mark Andrews (Environment Agency); Anj Beckham (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Andrew Cannon (Natural Surroundings); Claire Humphries (Environment Agency); Tim Jacklin (Wild Trout Trust); Kelly Powell (Norfolk County Council Historic Environment Service); Carl Sayer (University College London); Ian Shepherd (River Glaven Conservation Group); Mike Sutton-Croft (Norfolk Non-native Species Initiative); Jonah Tosney (Norfolk Rivers Trust) Cover Photos Clockwise from top left: Wiveton Bridge (©Evelyn Simak and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Glandford Ford (©Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); River Glaven above Glandford (©Oliver Dixon and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence); Swan at Glandford Ford (© Ashley Dace and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence). ii CONTENTS Foreword – Gemma Clark, 9 Chalk Rivers Project Community Involvement Officer. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

North Norfolk District Council (Alby

DEFINITIVE STATEMENT OF PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY NORTH NORFOLK DISTRICT VOLUME I PARISH OF ALBY WITH THWAITE Footpath No. 1 (Middle Hill to Aldborough Mill). Starts from Middle Hill and runs north westwards to Aldborough Hill at parish boundary where it joins Footpath No. 12 of Aldborough. Footpath No. 2 (Alby Hill to All Saints' Church). Starts from Alby Hill and runs southwards to enter road opposite All Saints' Church. Footpath No. 3 (Dovehouse Lane to Footpath 13). Starts from Alby Hill and runs northwards, then turning eastwards, crosses Footpath No. 5 then again northwards, and continuing north-eastwards to field gate. Path continues from field gate in a south- easterly direction crossing the end Footpath No. 4 and U14440 continuing until it meets Footpath No.13 at TG 20567/34065. Footpath No. 4 (Park Farm to Sunday School). Starts from Park Farm and runs south westwards to Footpath No. 3 and U14440. Footpath No. 5 (Pack Lane). Starts from the C288 at TG 20237/33581 going in a northerly direction parallel and to the eastern boundary of the cemetery for a distance of approximately 11 metres to TG 20236/33589. Continuing in a westerly direction following the existing path for approximately 34 metres to TG 20201/33589 at the western boundary of the cemetery. Continuing in a generally northerly direction parallel to the western boundary of the cemetery for approximately 23 metres to the field boundary at TG 20206/33611. Continuing in a westerly direction parallel to and to the northern side of the field boundary for a distance of approximately 153 metres to exit onto the U440 road at TG 20054/33633. -

Norfolk Rivers Trust Partnership River Stiffkey Total Catchment Solution Balancing Nutrients

Norfolk Rivers Trust Partnership River Stiffkey Total Catchment Solution Balancing Nutrients 1 Mission Statement: Norfolk Rivers Trust’s mission is to enhance the value of the aquatic landscape through encouraging natural processes, with benefits for wildlife and people. Funding for this project • Environment Agency 4 Years • Natural England • World Wildlife Fund • Tesco, Asda, J Sainsbury,Courtauld 2025 • Utility Companies • Land Owners • Local Funders – Wind – Solar - Other Phases of the Project • Phase 1 Current – Walk Overs – Farm Visits – Establish nutrient inflows and Create total Catchment Partnership Plan • Phase 1 a Deliver plan to local community and partners • Phase 2 Establish Additional Funding – Permissions – Permits and Water planning • Phase 3 Deliver improvement • Phase 4 Measure against set Catchment Water Quality Objectives 4 Examples of Silt Trap Interventions Integrated Constructed Wetlands Options Forest and Industrial (food ponds processing) intercepting Flood attenuation wastewater land drainage and treatment treatment Water management through the coherent reanimation of ‘integrated’ constructed wetland types In situ Recreational treatment of Municipal wastewater self cleansing landfill leachate treatment swimming pond Impact Nar silt traps and LWD 350 300 250 Lexham 200 Castle 150 Acre Manor 100 Farm 50 0 2010 2013 2015 Fish numbers on Nar: EA Electro-fishing data 2015 EA Stiffkey Map 8 WATER QUALITY IN THE STIFFKEY AND GLAVEN CATCHMENTS AND BLAKENEY HARBOUR Estuaries and Coasts Partnership Fund Project Summary ABOUT THE PROJECT WE DID NOT FIND EVIDENCE OF SIGNIFICANT WATER QUALITY PROBLEMS POSED TO THE ESTUARY FROM THE STIFFKEY AND GLAVEN CATCHMENTS Blakeney Harbour (Norfolk) offers excellent opportunities for Why do we think this? fishing, sailing and bathing and functions as a nursery and feeding ground for many species of birds, finfish and shellfish. -

Norfolk Coast Partnership Member Organisations

CELEB 3 RAT 01 IN -2 G 4 2 9 0 9 Y 1 E A N R A S I O D R Norfolk Coast F A T U 20 H G YEARS E T N S O A R O F C O L GUARDIANK FREE guide to an area of outstanding natural beauty 2013 GET AROUND Discover and enjoy Coasthopper offers, competitions and walks CONNECT Help NWT appeal to join marshes ENJOY Events, Recipes, Art MARINE MARVELS SEALIFE SPECIAL 2 A SPECIAL PLACE NORFOLK COAST GUARDIAN 2013 NORFOLKNOR COAST THE NORFOLK COAST PPARTNERSART PARTNERSHIP NaturalNat England South Wing at Fakenham Fire Station, NorfolkNo County Council Norwich Road, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8BB T: 01328 850530 NoNorth Norfolk District Council E: offi[email protected] BoroughBorou Council of King’s Lynn W: www.norfolkcoastaonb.org.uk & West Norfolk Manager: Tim Venes Great Yarmouth Borough Council Policy and partnership officer: Estelle Hook Broads Authority Communications officer: Lucy Galvin Environment Agency Community and external funding English Heritage officers: Kate Dougan & Grant Rundle Business support assistant: Steve Tutt Norfolk Wildlife Trust Funding Partners National Trust DEFRA; Norfolk County Council; RSPB North Norfolk District Council; Country Land & Business Association Borough Council of King’s Lynn & West Norfolk National Farmers Union and Great Yarmouth Borough Council Community Representatives AONB Common Rights Holders The Norfolk Coast Guardian is published by Countrywide Publications on behalf of the Norfolk Wells Harbour Commissioners Coast Partnership. Editor: Lucy Galvin. Designed and produced by: Countrywide Publications The Wash and North Norfolk Coast T: 01502 725870. Printed by Iliffe Print on sustainable newsprint. -

Annual Report 2019–2020

Norfolk Wildlife Trust Annual report 2019–2020 Saving Norfolk’s Wildlife for the Future Norfolk Wildlife Trust seeks a My opening words are the most important message: sustainable Living Landscape thank you to our members, staff, volunteers, for wildlife and people donors, investors and grant providers. Where the future of wildlife is With your loyal and generous in the School Holidays. As part of our Greater support, and despite the Anglia partnership we promoted sustainable protected and enhanced through challenges of the current crisis, travel when discovering nature reserves. sympathetic management Norfolk Wildlife Trust will continue to advance wildlife We have also had many notable wildlife conservation in Norfolk and highlights during the year across all Norfolk Where people are connected with, to connect people to nature. habitats, from the return of the purple emperor inspired by, value and care for butterfly to our woodlands, to the creation of a Norfolk’s wildlife and wild species This report covers the year to the end of March substantial wet reedbed at Hickling Broad and 2020, a year that ended as the coronavirus Marshes in conjunction with the Environment crisis set in. Throughout the lockdown period Agency. Many highlights are the result of we know from the many photos and stories partnerships and projects which would not we received and the increased activity of our have been possible without generous support. CONTENTS online community that many people found nature to be a source of solace – often joy – in The Prime Minister had said that the Nature reserves for Page 04 difficult times. -

( 279 ) Ornithological Notes from Norfolk for 1924. In

( 279 ) ORNITHOLOGICAL NOTES FROM NORFOLK FOR 1924. BY B. B. RIVIERK, F.R.C.S., F.Z.S., M.B.O.U. IN presenting my report on the Ornithology of Norfolk for the year 1924, I again acknowledge with grateful thanks the valuable assistance I have received from a number of correspondents who have sent me notes. I have also to record, with very deep sorrow, the loss of two most valued contributors to these notes in the Rev. Maurice C. H. Bird of Brunstead, who died on October 18th, 1924, in his sixty- eighth year, and in Mr. H. N. Pashley of Cley, who died on January 30th, 1925, in his eighty-first year. The past year was chiefly notable for the extraordinary number of wild fowl which visited our coasts during January and February, and for the record bags of Woodcock which continued to be made up to the end of the 1923-24 shooting season. Of these two remarkable immigrations I have already written elsewhere (Trans. Norf. <& Norwich Nat. Soc, Vol. XL, pt. v., 1923-24), so that I shall only refer to them more briefly in these notes. The winter of 1923-24, which was a long and bitterly cold one, may be said to have begun at the end of the first week of November, and lasted well into March. The first two weeks of January were marked by frosts and blizzards, a particularly severe blizzard from the S.E. occurring on the night of the 8th, whilst from February -12th until the end of the month snow fell nearly every day, the thermometer on February 29th registering 120 of frost, and another heavy snowfall occurring on March 3rd. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

The Norfolk & Norwich

TRANSACTIONS OF THE NORFOLK & NORWICH NATURALISTS' SOCIETY VOL. XXIII 1974 - 1976 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS Page Allard, P. R. 29 Banham, P. R. 145 Buckley, J 86,172 Funnell, B.M 251 Gosling, L. M 49 Gurney, C Ill Harding, P. T 267 Harrison, R. H 45 Hornby, R 231 Ismay, J 231, 271 Kington, J. A. 140 Lambley, P. W 170, 231, 269, 270 Norgate, T. B 167 Oliver, J 120 Peet, T. N.D 156,249 Ramsay, H. R. 28 Watts, G. D 231 Williams, R. B 257 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (Plates adjoin pages indicated) Bat, Long-eared 60 Bearded Tit 95 Bewick's Swan ••• 103 Black-bellied Dipper ... ... ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 44 Black-headed Gull 29 Black-tailed Godwit ... ... ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 87 Common Tern ••• 94 Curlew ••• 216 Deer, Roe 61 Page Green Sandpiper ... ... ... 216 Hawfinch 79 Heron Hortus Sanitatus, figures from 117 Kingfisher 200 Knot 28 Lapwing 102 Little Egret 12 Little Ringed Plover ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 Osprey 102 Pied Flycatcher 44 217 Pyiausta peilucidalis 249 Red-breasted Flycatcher ... ... 44 Salt Pans 150-151 Sandwich Tern 28,201 Short-eared Owl ... ... ... ... ... 45 Snipe 200 Sparrowhawk 44 Squirrel, Grey 60 Water-rail 13 Waxwing 78,201 Weather Maps, Europe, 1784 143- 144 White-fronted Goose 45 Wryneck 217 Yare Valley 247 - 249 INDEX TO VOLUME XXIII Amphibia and Reptile Records for Norfolk ... ... 172 Barton Broad, Bird Report ... ... ... ... 5 Bird Report, Classified Notes 1972 30 1973 96 1974 202 Bird Report, Editorial 1972 2 1973 71 1974 194 Bird Ringing Recoveries 22, 92, 197 Birds and the Weather of 1784 140 Blakeney Point, Bird Report 5 Breydon Water, Bird Report .. -

Sheetlines the Journal of the CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps

Sheetlines The journal of THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps “Agas to OS” Nick Millea Sheetlines, 112 (August 2018), pp51-53 Stable URL: https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/sheetlines- articles/Issue112page51.pdf This article is provided for personal, non-commercial use only. Please contact the Society regarding any other use of this work. Published by THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps www.CharlesCloseSociety.org The Charles Close Society was founded in 1980 to bring together all those with an interest in the maps and history of the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain and its counterparts in the island of Ireland. The Society takes its name from Colonel Sir Charles Arden-Close, OS Director General from 1911 to 1922, and initiator of many of the maps now sought after by collectors. The Society publishes a wide range of books and booklets on historic OS map series and its journal, Sheetlines, is recognised internationally for its specialist articles on Ordnance Survey-related topics. 51 Agas to OS: Oxford’s changing townscape in old maps and new Nick Millea Imagine a new map showing the historical layout of a familiar town on a modern cartographic background. Better still, imagine a series of maps showing the urban development of that town on the same modern cartographic background at various different stages over the past thousand years. If you are interested in British towns, then this work may well have been completed for somewhere which is very well known to you. The Historic Towns Atlas programme was started in 1955 by the Commission Internationale pour l’Histoire des Villes (International Commission for the History of Towns (ICHT)) of the Comité Internationale des Sciences Historiques. -

Seaport - City Name & Code Tên & Mã Các C Ảng Bi Ển - Đị a Điểm

HANLOG LOGISTICS TRADING CO.,LTD No. 4B, Lane 49, Group 21, Tran Cung Street Nghia Tan Ward, Cau Giay Dist, Hanoi, Vietnam Tel: +84 24 2244 6555 Hotline: + 84 913 004 899 Email: [email protected] Website: www.hanlog.vn SEAPORT - CITY NAME & CODE TÊN & MÃ CÁC C ẢNG BI ỂN - ĐỊ A ĐIỂM Mã/Code Tên thành ph ố/City Mã qu ốc gia/Country Code Tên qu ốc gia/Country Name AFBIN BAMIAN AF Afganistan AFBST BOST AF Afganistan AFCCN CHAKCHARAN AF Afganistan AFDAZ DARWAZ AF Afganistan AFFBD FAIZABAD AF Afganistan AFFAH FARAH AF Afganistan AFGRG GARDEZ AF Afganistan AFGZI GHAZNI AF Afganistan AFHEA HERAT AF Afganistan AFJAA JALALABAD AF Afganistan AFKBL KABUL AF Afganistan AFKDH KANDAHAR AF Afganistan AFKHT KHOST AF Afganistan AFKWH KHWAHAN AF Afganistan AFUND KUNDUZ AF Afganistan AFKUR KURAN-O-MUNJAN AF Afganistan AFMMZ MAIMANA AF Afganistan AFMZR MAZAR-I-SHARIF AF Afganistan AFIMZ NIMROZ AF Afganistan AFZZZ OTHER AF Afganistan AFLQN QALA NAU AF Afganistan AFSBF SARDEH BAND AF Afganistan AFSGA SHEGHNAN AF Afganistan AFTQN TALUQAN AF Afganistan AFTII TIRINKOT AF Afganistan AFURN URGOON AF Afganistan AFURZ UROOZGAN AF Afganistan AFZAJ ZARANJ AF Afganistan ALDRZ DURRES (DURAZZO) AL Albania ALZZZ OTHER AL Albania ALSAR SARANDE AL Albania ALSHG SHENGJIN AL Albania ALTIA TIRANA AL Albania DZALG ALGER DZ Algeria DZAAE ANNABA (EX BONE) DZ Algeria DZAZW ARZEW DZ Algeria DZBJA BEJAIA (FORMERLY BOU DZ Algeria DZBSF BENISAF DZ Algeria DZCHE CHERCHELL DZ Algeria DZCOL COLLO DZ Algeria DZCZL CONSTANTINE DZ Algeria DZDEL DELLYS DZ Algeria DZDJI DJIDJELLI DZ Algeria