Yearbook of Muslims in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punime Të Kuvendit Legjislatura E 16-Të Viti 2003, Nr.6 Përgatiti Për Botim Drejtoria E Shërbimit Të Botimeve Parlamentare PUNIME TË KUVENDIT Seancat Plenare

Punime të Kuvendit Legjislatura e 16-të Viti 2003, nr.6 Përgatiti për botim Drejtoria e Shërbimit të Botimeve Parlamentare PUNIME TË KUVENDIT Seancat plenare Viti 2003 6 Tiranë, 2009 REPUBLIKA E SHQIPËRISË Punime të Kuvendit Seancat plenare LEGJISLATURA E 16-të Sesioni i katërt E hënë, 01.09.2003 Drejton seancën Kryetari i Kuvendit, Seanca e pasdites, ora 18:00 zoti Servet Pëllumbi Servet Pëllumbi – Zotërinj deputetë, ju lutem emrin tuaj deputetët organizatorë dhe të uroj që zini vend në sallë! veprimtari të tilla me rezonancë të gjerë miqësie Të nderuar deputetë, është kënaqësi për mua, rajonale e ndërkombëtare të organizohen edhe në me rastin e fillimit të punimeve të sesionit të pestë të ardhmen. të legjislaturës së 16-të të Kuvendit të Shqipërisë, Në sesionin e mëparshëm, nga janari deri në t’ju uroj punë të mbarë dhe të shpreh bindjen se korrik, kemi bërë një punë intensive. Më shumë se fryma e parlamentarizmit, përkushtimit, 150 ligje e vendime të miratuara, më shumë se 50 konstruktivitetit dhe bashkëpunimit midis grupeve interpelanca dhe seanca pyetjesh të zhvilluara. Kjo parlamentare do të vazhdojë të karakterizojë punën përvojë është bazë e shëndoshë për të përballuar e Kuvendit tonë. Këtë na e mundëson puna e bërë detyrat e reja që qëndrojnë përpara Kuvendit. Në gjatë sesionit të kaluar dhe përvoja e fituar tashmë paketën e projektligjeve që kemi përpara do të veçoja në drejtim të vlerësimit të tribunës parlamentare, të si më problematik që do të kërkojnë angazhimin përgjegjësisë, seriozitetit, kompromisit politik dhe tonë serioz, veçanërisht për ligjet “Për kthimin dhe moderacionit të treguar. -

Televizoni Ora News

Televizioni Top –Chanel Zbatimi i kritereve të Integrimit Përpara publikimit të raportit të Komisionit Europian për Shqipërinë, fondacioni 'Soros' ka bere publik një studim të detajuar, sesa vendi ka përmbushur detyrimet që ka marrë përsipër. Ne studim nuk perfshihen dy prioritete qe lidhen me zgjedhjet, por megjithate vihet ne dukje se pika me e dobet e Shqiperise eshte moszbatimi i kriterit politik, ku eshte bere pak ose aspak progres krahasuar me nje vit me pare. "Kjo për shkak kryesisht dhe thelbësisht të mosvlerësimit të përpjekjeve që kërkohen dhe janë të domosdoshme në ato fusha ku kërkohet dhe progresi varet nga konsensusi politik. Në krahasim me një vit më parë, ritmi i Nga 102 masat e planifikuara per t’u zbatuar gjate vitit 2011 vetem 20% jane zbatuar, 76 % e masave te parashikuara jane pjeserisht te zbatuara, ndersa per 4% puna ende nuk ka filluar. Fondacioni 'Soros'reformave është ngadalësuar. Nga 102 masat e planifikuara per t’u zbatuar gjate vitit 2011 vetem 20% jane zbatuar, 76 % e masave te parashikuara jane pjeserisht te zbatuara, ndersa per 4% puna ende nuk ka filluar", thotë Andi Dobrushi, përfaqësues i fondacionit. Por ne punen per te monituar zbatimin e 12 prioriteteve per integrimin, fondacioni nuk duket se ka gjetur bashkepunim te plote me te gjithe zinxhirin e administrates, i cili ne shume raste ka injoruar kerkesat e tyre per pergjigje. Dhe kjo ndodh kur, progres raporti hartohet duke konsultuar sistematikisht shoqerine civile, sic tha perfaqesesi i Bashkimit Europian ne Tirane. "Për të përmbledhur një informacion cilësor për këtë raport, janë dërguar 50 kërkesa për informacion dhe takime në të gjithë njësitë e linjës dhe autoritetet përkatëse. -

The Struggle for Democratic Environmental Governance Around

The struggle for democratic environmental governance around energy projects in post-communist countries: the role of civil society groups and multilateral development banks by Alda Kokallaj A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014 Alda Kokallaj Abstract This dissertation focuses on the struggle for democratic environmental governance around energy projects in post-communist countries. What do conflicts over environmental implications of these projects and inclusiveness reveal about the prospects for democratic environmental governance in this region? This work is centred on two case studies, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline and the Vlora Industrial and Energy Park. These are large energy projects supported by the governments of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Albania, and by powerful international players such as oil businesses, multilateral development banks (MDBs), the European Union and the United States. Analysis of these cases is based on interviews with representatives of these actors and civil society groups, narratives by investigative journalists, as well as the relevant academic literature. I argue that the environmental governance of energy projects in the post-communist context is conditioned by the interplay of actors with divergent visions about what constitutes progressive development. Those actors initiating energy projects are shown to generally have the upper hand in defining environmental governance outcomes which align with their material interests. However, the cases also reveal that the interaction between civil society and MDBs creates opportunities for society at large, and for non-government organizations who seek to represent them, to have a greater say in governance outcomes – even to the point of stopping some elements of proposed projects. -

Rruga E Arbrit Në Pritje Të Votave “Pro” Të Deputetëve

Market KEN Laprakë, Tiranë Tel: +355 4 22 50 480480 Cel. 068 20 36 394394 www.rrugaearberit.comwww.rrugaearberit.com GAZETË GAZETË E PAVARUR. E PAVARUR. NR. NR. 3 (107).7 (87). MARS KORRIK 2015. 2013. Ç M ÇMIMI:IMI: 50 50 LEKË. LEKË. 20 20 DENARË. DENARË. 1.5 1.5 EURO. EURO. BUJQËSIKONTRIBUT JETËTURIZËM INTERVISTËSTUDIM RAECENSËRSIM MinistriMusa RiçkuCani: ËndrraVargmali e i HakiPotencialet Stërmilli - i BotaHistoria e nxehtë e arsimit e 1.9financon miliardë xhaminë lekë parealizuarDeshatit, aty e ku harruarie turizmit i madh erositdhe mendimit në poezinë në mbështetje vogëlushes Ebi Intervistë me studiuesin e Artan Gjyzel e re në Limjan nis zhvillimi... Xhezairmalor Abazi pedagogjik... të Ngafermerëve AHMET ÇAUSHI - FAQE 7FAQE 9 Nga BESNIK ALKU - FAQE 11 FAQE 13 Nga FATBARDH CENA - FAQE 12-13FAQE 10 HasanitNga PROF. DR. NURI ABDIU - FAQEFAQE 9 19 QEVSHËNIMERIA DORËZON NË PARLAMENT PROJEKTLIGJIN E POSAÇËM PËR DHËNIEN ME KONCENSION Solidarizohuni me Rrugarininë dibrane duke eRruga Arbrit në e pritjeArbrit të nënshkruar peticionin Nga Dr.GËZIM ALPION Të parandalohen ndryshimet, e, intelektualët dibranë, që po lobojmë për Nndërtimin e Rrugës së Arbrit nëpërmjet votavepeticionit online, jemi mrekulluar që në fillim“Pro” të deputetëve nga reagimi pozitiv i rinisë dibrane. Kemi marrë për të rritur cilësinë e ndërtimit Ndërsamesazhe ligji është nga një në numër i madh të rinjsh dibranë parlament,nga disa rihapet qytete, debatetsi në Shqipëri dhe Maqedoni, ashtu edhe nga disa vende në Evropë, përfshirë për Rrugën.edhe Australinë Pse po dhe hartohet Amerikën e largët. Ajo që na ka lënë mbresa është jo vetëm një ligjigatishmëria i posaçëm e tyre dhe për pseta nënshkruar peticionin anashkalohetdhe për të tenderi?inkurajuar Safamiljet, është miqtë dhe kolegët e tyre të bëjnë të njëjtën gjë, por edhe sugjerimet financimiqë na kanëdhe bërë kush se sido mund ta të lobojmë në mënyrë paguajsa rrugën? me të efektshme Sa do tëpër jenë ndërtimin e Rrugës së Arbrit. -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

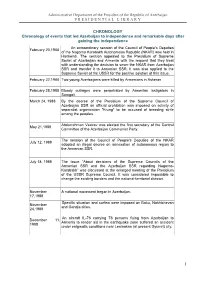

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CHRONOLOGY Chronology of events that led Azerbaijan to independence and remarkable days after gaining the independence An extraordinary session of the Council of People's Deputies February 20,1988 of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic (NKAR) was held in Hankendi. The session appealed to the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request that they treat with understanding the decision to sever the NKAR from Azerbaijan SSR and transfer it to Armenian SSR. It was also applied to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the positive solution of this issue. February 22,1988 Two young Azerbaijanis were killed by Armenians in Askeran February 28,1988 Bloody outrages were perpetrated by Armenian instigators in Sumgait March 24, 1988 By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan SSR an official prohibition was imposed on activity of separatist organization "Krung" to be accused of breeding strife among the peoples. Abdurrahman Vezirov was elected the first secretary of the Central May 21,1988 Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. The session of the Council of People's Deputies of the NKAR July 12, 1988 adopted an illegal decree on annexation of autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. July 18, 1988 The issue “About decisions of the Supreme Councils of the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR regarding Nagorno- Karabakh” was discussed at the enlarged meeting of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council. -

Social Status of 'Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi' in Present-Day Azerbaijan

Social status of ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ in present-day Azerbaijan ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ as counter-balance Year: 2015 Place of fieldwork: Republic of Azerbaijan Name:Ko Iwakura Keywords: Azerbaijan, Control policy on Islam, ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’, Minority Sunni, Counter-balance Research background Azerbaijan is a country comprising approximately 70% Shia and 25% Sunni Muslims, while the national majority are Azerbaijanis (descended from the Turkic people). We can see the authority of secularism through the government’s control policy on Islam and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’, which is a society organization that controls Ulama (Islamic law scholars) and mosques. In fact, when walking around an Azerbaijani town, we can observe women not wearing headscarves, alcohol and pork being sold and consumed, and other examples of non-Islamic practices. Conversely, despite government and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ policies, uncontrollable Islamic social organizations are active. To limit them, laws and police powers are exercised to manage the current situation. Research purpose and aim Prior research on the management of uncontrollable Islamic social organizations has either neglected or ignored the roles of the government and ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’. Unlike prior research, this study focuses on the policies of ‘Qafqaz Müsəlmanları İdarəsi’ on Islam and social status. Focusing on these points, it is possible to provide the government’s perspectives, rather than only the perspectives from outside the government, on the nature of Islam in Azerbaijan. Furthermore, I consider that this research can contribute not only to policies in Azerbaijan but also to enhancing understanding of the relationship between Islam and the governments of former Soviet and socialist bloc nations. -

Problems of Muslim Belief in Azerbaijan: Historical and Modern Realities

ISSN 2707-4013 © Nariman Gasimoglu СТАТТІ / ARTICLES e-mail: [email protected] Nariman Gasimoglu. Problems of Muslim Belief іn Azerbaijan: Historical аnd Modern Realities. Сучасне ісламознавство: науковий журнал. Острог: Вид-во НаУОА, 2020. DOI: 10.25264/2707-4013-2020-2-12-17 № 2. C. 12–17. Nariman Gasimoglu PROBLEMS OF MUSLIM BELIEF IN AZERBAIJAN: HISTORICAL AND MODERN REALITIES Religiosity in Azerbaijan, the country where vast majority of population are Muslims, has many signs different to what is practiced in other Muslim countries. This difference in the first place is related to the historically established religious mentality of Azerbaijanis. Worth noting is that history of this country with its Shia Muslims majority and Sunni Muslims minority have registered no serious incidents or confessional conflicts and clashes either on the ground of inter-sectarian confrontation or between Muslim and non-Muslim population. Azerbaijan has never had anti-Semitism either; there has been no fact of oppression of Jewish people living in Azerbaijan for many centuries. One of the interesting historic facts is that Molokans (ethnic Russians) who have left Tsarist Russia when challenged by religious persecution and found asylum in neighborhoods of Muslim populated villages of Azerbaijan have been living there for about two hundred years and never faced problems as a religious minority. Besides historical and political reasons, this should be related to tolerance in the religious mentality of Azerbaijanis as well. Features of religion in Azerbaijan: historical context Most of the people living in Azerbaijan were devoted to Tengriism (Tengriism had the most important place in the old belief system of ancient Turks), Zoroastrianism and Christianity before they embraced Islam. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe the Titles Published in This Series Are Listed at Brill.Com/Yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 4

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 4 Editor-in-Chief Jørgen S. Nielsen Editors Samim Akgönül Ahmet Alibašić Egdūnas Račius LEIDEN • boSTON 2012 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1877-1432 ISBN 978-90-04-22521-3 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-23449-9 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS The Editors ........................................................................................................ ix Editorial Advisers ........................................................................................... -

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe the Titles Published in This Series Are Listed at Brill.Com/Yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 5

Yearbook of Muslims in Europe The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/yme Yearbook of Muslims in Europe Volume 5 Editor-in-Chief Jørgen S. Nielsen Editors Samim Akgönül Ahmet Alibašić Egdūnas Račius LEIDEN • boSTON 2013 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1877-1432 ISBN 978-90-04-25456-5 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25586-9 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS The Editors ........................................................................................................ ix Editorial Advisers ........................................................................................... -

E MAJTA Mendimi Politik / Profile Biografike

E MAJTA Mendimi Politik / Profile Biografike Tiranë. 2020 Botues -Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Zyra e Tiranës Rr. “Kajo Karafili” Nd-14, Hyrja 2, Kati 1, Kutia Postare 1418, Tiranë, Shqipëri - Autoriteti për Informimin mbi Dokumentet e ish-Sigurimit të Shtetit Rruga “Ibrahim Rugova”, nr. 11, Tiranë, Shqipëri Autorë Prof. Dr. Ana Lalaj Dr. Dorian Koçi Dr. Edon Qesari Prof. Dr. Hamit Kaba Dr. Ilir Kalemaj Prof. Asoc. Dr. Sonila Boçi Ndihmuan në përgatitjen e këtij botimi: Ardita Repishti - Drejtoreshë e Mbështetjes Shkencore dhe Edukimit Qytetar, AIDSSH Jonida Smaja - Koordinatore Programi, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Design Grid Cartels Shtëpia Botuese Gent Grafik Kërkimet shkencore dhe analizat e ndërmarra për këtë botim janë të autorëve dhe nuk reflektojnë domosdoshmërisht ato të Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert. Publikimet e Fondacionit Friedrich Ebert nuk mund të përdoren për arsye komerciale pa miratim me shkrim. Përmbajtje 26 10 Sejfulla Malëshova 6 HyrjeH ParathënieP 72 Tajar Zavalani 52 86 Konstandin Çekrezi Musine Kokalari 118 Skënder Luarasi 140 104 Petro Marko Isuf Luzaj 180 Isuf Keçi 162 200 Zef Mala Xhavid Qesja Parathënie Mendimi politik i së majtës shqiptare E majta shqiptare jomonolite, me dinamikat e zhvillimit të saj në rrafshin kombëtar dhe europian, me zgjedhjet dhe vendimet për marrjen e mbajtjen e pushtetit në përfundim dhe pas Luftës së Dytë Botërore, ka qenë prej kohësh sfidë për t’u trajtuar. Gentjana Gjysmëshekulli komunist që e fshiu mendimin ndryshe, që e retushoi të shkuarën Sula dhe emrat e përveçëm që patën ndikim në vend, u kujdes të vetëparaqitej me dorë të fortë, si e majtë e unifikuar që në fillime, e gjithëpranuar nga populli, e cila e mbajti pushtetin për popullin.