Download TRI News Vol 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

District Census Handbook, Kameng, Part X, Series-24, Arunachal Pradesh

CENSUS OF INDIA- 1971 Series No. 24 ARUNACHAL PRAI)ESH PART X DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK KAMENG DISTRICT Part A: TOWN & VILLAGE--DIREGTORY Part B : ,URBAN BbOCK I VILLAGEWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT J. K. Barthakur, of tke Indian Frontier Administratwe Service~ Director of Census Operat~ ~unoohal-prau~--- , Shillong-3 ·A'P.(u. ~ Statements made. views expressed or con clusions drawn in this report are wholly the responsibil ity of the author alone in his perso nal capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government. Arunachai ~ad* is til thinly pbpuitilted hiIiy tract lying touah1v be'" ween the latitudes ~ and 29"3O'N and the longitudes 91.°3O'E and,97°30'E on the north east extremity of India, compi-ising roughly of 83,578 kilometre squares of area. bordering the international boundaries of Bhutan. Tibet, China and Burma. The Pradesh is known to be rich in flora. fauna, power and mine ral potentia1. When the 1971 Census was taken in Arunachal Pradesh, the area was known as the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA in short) which was consti tutionally a part of ~e State of AsSam. At that time NEFA was directly_ ad ministered by the President of India through the Governor of Assam as his agent, who was assisted by an adviser. The office_ of the Adviser to the Gover· nor of AssQUl was situated at Shillong, t~e capital of the Assam. State. On the 21st -JanUary, 1972, NEFA haa been ttlade into a Union Territory under the provision of the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act. -

Language Monograph, Survey of Kanauri in Himachal Pradesh

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 MONOGRAPH NO. 3 SERIES I LANGUAGE MONOGRAPH (1961 SERIES) FOREWORD A. MITRA OF THE INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE REGISTRA R GENERAl AND CENSUS COMMISSIONER, INDIA. ~URVEY OF KANAURI GENERAL SUPERVISION AND GUIDANCE IN R. C. NIGAM, LlNG1!IST. INVEST/GArrON AND Hflt'IACHAL PRADESH '''IVANAN, LANGUAGE DIVISION OFFICE l_ 'THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA CONTENTS PAGES FOREWORD-DR. ASOK MITRA • • • i NOTE-SHRI R. C. NIGAM • iii INTRODUCTION • • • 1 PHONOLOGY . 10 MORPHO-PHONEMICS 24 MORPHOLOGy 21 CURRENT TRENDS AND ARYAN INFLUENCE • 45 KANAURI GLOSSARY (KALPA DIALECT) • 59 UNCONNECTED TEXTS 80 CONNECTED TEXTS 81 FREE TRANSLATION 88 " FOREWORD This Survey of Kanauri in Himachal Pradesh is one of several undertaken by Sri R. C. Nigam, Assistant Registrar General and Linguist, and his colleagues in pursuance of a decision taken in the early years of the last decade to conduct inquiries into specific speeches belonging to the Himalayan Group along the lower slopes of the Himalayas on the lines of the great Linguistic Survey of India. The reason why certain languages along the lower slopes of the Himalayas were chosen for particular inves ... tigation has been explained in Sri Nigam's Prefatory Note. The chief aim was to inquire into the uncertainties of their origins, affiliations, specific features as contact languages and to assess how these speeches were themselves being gradual1y transformed through a variety of contacts over time. The inquiries could be entrusted only to trained specialists who would be prepared to undertake field inves .. tigation of adequate duration and satisfactory coverage. The investigators were, in addition, to have the right aptitude to be sufficiently accepted in the life of the particular language group to be initiated into their idiom. -

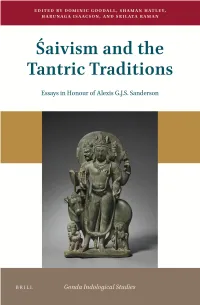

Download: Brill.Com/Brill‑Typeface

Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Alexis G.J.S. Sanderson Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions Essays in Honour of Alexis G.J.S. Sanderson Edited by Dominic Goodall Shaman Hatley Harunaga Isaacson Srilata Raman LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Standing Shiva Mahadeva. Northern India, Kashmir, 8th century. Schist; overall: 53cm (20 7/8in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. Severance A. Millikin 1989.369 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sanderson, Alexis, honouree. | Goodall, Dominic, editor. | Hatley, Shaman, editor. | Isaacson, Harunaga, 1965- editor. | Raman, Srilata, editor. Title: Śaivism and the tantric traditions : essays in honour of Alexis G.J.S. -

SOUTH ASIA STATE of MINORITIES REPORT 2019 Migrants, Refugees and the Stateless

SOUTH ASIA STATE OF MINORITIES REPORT 2019 Migrants, Refugees and the Stateless THE SOUTH ASIA COLLECTIVE SOUTH ASIA STATE OF MINORITIES REPORT 2019 SOUTH ASIA STATE OF MINORITIES REPORT 2019 Migrants, Refugees and the Stateless THE SOUTH ASIA COLLECTIVE South Asia State of Minorities Report 2019 Migrants, Refugees and the Stateless Edited by a team at Social Science Baha, Kathmandu, consisting of Deepak Thapa, Sudeshna Thapa and Ritika Singh. This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the South Asia Collective and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or Norad. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercialShareAlike 4.0 International License. Provided they acknowledge the source, users of this content are allowed to remix, tweak, build upon and share for noncommercial purposes under the same original license terms. ISBN: 978 9937 0 7248 9 First Edition: 2020 Cover design: Norbo Lama Design and layout of text pages: Chiran Ghimire Contents Foreword vii Acknowledgements xi Note on the South Asia Collective xiii Note on Contributors xv Abbreviations and Acronyms xix Introduction xxiii Chapter 1 Religious Minorities in Afghanistan: The Victims 1 of Negligence Chapter 2 The State of Statelessness in Bangladesh: An Overview 15 Chapter 3 Migrants, Refugees and the Stateless in India: Deploying 32 Citizenship to Redefine the Secular State Chapter 4 Living in Limbo: Tibetan and Bhutanese Refugees in Nepal 65 Chapter 5 Pakistan: The Struggle for Equal Citizenship 91 Chapter 6 Sri Lanka: Discrimination Against Religious Minorities 110 and Its Impact on Inclusion in a Plural Society Chapter 7 State of Minorities in South Asia, 2019 138 Foreword In recent years, the particular challenges concerning the right to nationality for minorities have gained increasing recognition. -

Bulletin Zoölogisch Museum

Bulletin Zoölogisch Museum UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM Vol.12 No. 1 1989 Zoogeography of the fishes from Indochinese Inland waters with an annotated check-list Maurice Kottelat Contents Introduction 1 and 2 Geographical scope terminology Check-list 3 Discussion A. Generalities 21 B. Inter-basin connections ; 34 C. Heuristic comments on some ichthyogeographical theories involving South-East Asia 37 Bibliography 43 INTRODUCTION Smith (1945) for Thailand, Taki (1974) for the Mekong According to an unpublished bibliography of Indochi- basin in Laos and Kottelat (1985) for the cyprinids of nese freshwater fishes that I completed, 930 native Kampuchea. Day (1875-78, 1888) is still the last com- fish species are known to occur in the inland waters plete reference to Burmese and Indian fishes; Jaya- of the Indochinese Peninsula, certainly making it one ram (1981) presents a more recent compilation for In- of the areas with the most diverse ichthyofauna. diaand Burma, but as far as Burma is concerned, the The study of this rich fish fauna is still in the discov- coverage cannot be satisfactory as the author had ac- ery and survey stage and there is presently no up-to- cess only to material collected before 1940. Mohsin & date reference work for this area. There are few use- Ambak’s (1983) book on western Malaysian fishes ful identification guides for the various countries: suffers from several important flaws (see for example 2 Zakaria-Ismail, 1983) and appears to be merely a Fonds National Suisse pour la Recherche Scienti- summary of the [few] specimens collected by the au- fique. thors. At the border of our area, Weber & de Beau- fort’s (1913-1916) monographs on Cypriniformes and AND Siluriformes are still the major source of information GEOGRAPHICAL SCOPE TERMINOLOGY The is the fish fauna on Indonesian freshwater fishes; Inger & Chin (1962) present discussion centered on of the Peninsula, the and Salween ba- present a useful reference for Sabah. -

Quantifying the Estimation and Abundance of Plant Diversity Of

ACCESS Freely available online atholog OPEN P y & nt a M l i P c f r o o b l i a o l n o r Journal of g u y o J ISSN: 2157-7471 Plant Pathology & Microbiology Research Article Quantifying the Estimation and Abundance of Plant Diversity of Shigar Valley, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan Saif Ullah1, Muhammad Zaman2, Liu Jiaqi1, Yaseen Khan3, Shakir Ullah4, Tian Gang1* 1College of Economics and Management, Northeast Forestry University, China; 2College of Wildlife Resource, Northeast Forestry University, China; 3Key Laboratory of Plant Nutrition and Agri-environment in Northwest China, Ministry of Agriculture, College of Natural Resources and Environment, Northwest A&F University, China; 4Key Laboratory of Plant Ecology, Northeast Forestry University, P.R. China ABSTRACT The studies were carried out from July 2017 to March 2018 in Shigar valley different Union Councils. The area lies between 7444 feet to 11694 feet from Above sea level in the Alpine zone including, Niali Nallah, Laxar Nallah, Nallah, Markuja union, Marapi union, Chorkah union, Gulapur. The study sites were randomly selected based on (1) herbs or shrubs land on the field periphery, (2) open grassland and arable land associated with sparse vegetation on rocks, stones, (3) forest land and open lands associated with sparse tree vegetation catchment of river and (4) forest land and arable land associated with dunes and rocky terrain. The quadrate method was used to record of vegetation from the selected study sites. A total of 59 plants species both medicinally and economically important were recorded at four study sites of CKNP and revealed that 30 herbs followed by 14 trees, 11 kinds of grass, and 4 shrubs respectively the dominant tree species recorded from all habitat types were Juniper sexcelsa, Elaeagnus ambulate, Morus alba, Salix Wilhelmina and Populus nigra. -

Rashmi Sanghi Editor Our National River Ganga Lifeline of Millions Our National River Ganga

Rashmi Sanghi Editor Our National River Ganga Lifeline of Millions Our National River Ganga Rashmi Sanghi Editor Our National River Ganga Lifeline of Millions Editor Rashmi Sanghi Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur , India ISBN 978-3-319-00529-4 ISBN 978-3-319-00530-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-00530-0 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013952900 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

SIKKIM Just Watchoutforthoseinfamousleeches

© Lonely Planet Publications 568 SIKKIM SIKKIM Sikkim If you’re feeling jaded by the heat and hassles of India, Sikkim is the perfect antidote. It’s clean (plastic bags are banned) and the mountain air is fresh. Best of all the people are among India’s most friendly, with a charming manner that’s unobtrusive and slightly shy. To really savour some true Sikkimese atmosphere, visit a village tongba-bar for some local millet beer: it’s a bit like warm Japanese sake. Plunging mountain valleys are lushly forested, interspersed occasionally with rice terraces and groves of flowering rhododendrons. Tibetan-style Buddhist monasteries (gompas) add splashes of vermilion to the green ridgetops and are approached through atmospheric avenues of colourful prayer flags set on long bamboo poles. Straddling the Sikkim–Nepal border is Khangchendzonga (Kanchenjunga; 8598m), the world’s third-highest mountain. Khangchendzonga’s guardian spirit is worshipped in a series of spectacular autumn festivals and its magnificent multiple white peaks can be spied from many points around the state. An independent kingdom until 1975, Sikkim has long been considered one of the last Himalayan Shangri Las. But hurry. In the last few years a tourist boom has seen ever multiply- ing numbers of visitors, mostly middle-class Bengalis escaping the Kolkata heat. Every year more concrete hotels protrude from once-idyllic villagescapes and most towns are already architecturally lacklustre huddles of multistorey box-homes. Fortunately, although Sikkim is tiny, its crazy contours make road construction very tough. So for now, finding the ‘real’ Sikkim is just a matter of hiking away from the metalled roads. -

Chapter 3 China and the World

CHAPTER 3 CHINA AND THE WORLD SECTION 1: CHINA AND SOUTH ASIA Introduction Although China’s assertiveness in Southeast Asia—particularly when it comes to the South China Sea—tends to dominate discourse about China’s growing global ambitions, China has also been active in cultivating infl uence among South Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka). This section surveys China’s economic, diplomatic, and se- curity engagement with South Asia. In addition to discussing Chi- na’s overarching objectives in the region, it profi les China’s relation- ships with South Asia’s two largest countries: India and Pakistan. It concludes with an examination of how China’s South Asia policies impact the United States, which also has signifi cant and evolving interests in the region. This section draws from the Commission’s March 2016 hearing on China-South Asia relations; its June 2016 fact-fi nding trip to China (Beijing and Kunming) and India (New Delhi and Mumbai); consultations with experts on Chinese and South Asian economics, foreign policy, and security affairs; and open source research and analysis. China’s Objectives in South Asia China has not publicly articulated a formal South Asia “strategy,” although Beijing’s key objectives and interests in the region can be observed in its activities in and diplomacy toward these countries. The key interests, concerns, and objectives of China’s South Asia strategy fall into four broad categories: (1) checking India’s rise by exploiting the India-Pakistan rivalry, (2) expanding economic activ- ity and infl uence in the region, (3) enhancing access to the Indian Ocean, and (4) countering terrorism and religious extremism (often at the expense of religious freedom and other human rights). -

BCSE 2011-2015 Performance Report

Excellence in Service FOREWORD The recruitment and selection of university graduates into the Civil Service is carried out by the Royal Civil Service Commission annually through Bhutan Civil Service Examination (BCSE). Civil Service recruitment examination for university graduates was introduced in 1983 with the objective of streamlining and instituting a proper selection system. Over the years, the recruitment and selection system has been strengthened to attract and select the most qualified and competent graduates through healthy and fair competition for appointment in the Civil Service based on the principle of meritocracy. This is a report on performance of graduates from different institutes in BCSE for the last five years: 2011 – 2015. Given the limited number of institutes for higher learning in the country, there are candidates from a number of different institutes based in different countries appearing the BCSE. For example, there were 1686 candidates from 183 different institutes based in 12 different countries who appeared BCSE in 2011. Similarly, there were 2397 candidates who studied in 229 different institutes based in 11 different countries in 2012. However, in 2013, there were 288 institutes where 3332 candidates graduated from, which was the maximum. In 2014 and 2015, there were 2892 and 3322 candidates from 241 and 260 different institutes appearing BCSE respectively. While there are a few candidates who studied in institutes based in countries such as Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, China, Cuba, England, Germany, Malaysia, Nepal, Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand and USA, most candidates who study outside Bhutan are from institutes based in India given its proximity and affordability.