Bullfrog Creek Management Plan Update, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingsnakems RWM

Godley et al. !1 Ecology of the Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) at Rainey Slough, Florida: A Vanished Eden J. STEVE GODLEY1, BRIAN J. HALSTEAD", AND ROY W. MCDIARMID# $Cardno, 3905 Crescent Park Drive, Riverview, FL, 33578, USA "U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Dixon Field Station, 800 Business Park Drive, Suite D, Dixon, CA, 95620, USA #U.S. Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 111 PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, 20013, USA CORRESPONDENCE: email, [email protected] RRH: ECOLOGY OF KINGSNAKES !1 Godley et al. !2 ABSTRACT: The Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) is an important component and predator in herpetofaunal communities, but many of its populations have declined precipitously in the last few decades, particularly in the southeastern USA. Here, we describe an intensive mark–recapture study of L. getula conducted from 1974–1978 in a canal bank–water hyacinth community at Rainey Slough in southern Florida, where we also quantitatively sampled their primary prey, other species of snakes. The best-fit model for L. getula was an open population with a high daily capture probability (0.189) and low apparent annual survival (0.128) that were offset by high recruitment and positive population growth rates, suggesting a high turnover rate in the population. Mean population size varied annually from 11–19 adult kingsnakes with a total predator biomass of 8.20–14.16 kg in each study year. At this site kingsnakes were susceptible to capture mostly in winter and spring, were diurnal, used rodent (Sigmodon hispidus) burrows on canal banks as nocturnal retreats, and emerged from burrows on 0.13–0.26 of the sampling days. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA Comunidades De

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE BIOLOGIA ANIMAL Comunidades de macroinvertebrados e peixes associadas à pradaria marinha de Halodule wrightii (Ascherson, 1868) na Laguna do Mussulo, Angola Carmen Ivelize Van-Dúnem do Sacramento Neto dos Santos Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade Agostinho Neto Bolseira FCT - Portugal (BD/423/95) INAB – Angola (11/01/002) Dissertação para Doutoramento (Biologia Marinha e Aquacultura) Dissertação orientada por: Professora Catedrática Maria José Costa Professora Auxiliar Maria Teresa Teixeira Lopes Alves de Matos Lisboa 2007 Dedico este trabalho à minha mãe querida, O meu coração quebrou-se Como um bocado de vidro Quis viver e enganou-se... Fernando Pessoa, poesias inéditas ...... Tudo é fugaz entre o desenho do teu pé na areia e a onda que desfaz a marca. Entre a guerra e a paz. Retorno fisicamente o poema onda constante meditação primeira. Nós e as coisas. Nada permanece que não seja para a necessária mudança. Que o diga o mar. Manuel Rui Monteiro (Mar novo in Cinco vezes onze - poemas em Novembro) RESUMO A faixa intertidal da pradaria da fanerogâmica marinha de H. wrightii situada na Laguna do Mussulo, Angola, foi estudada com o objectivo de identificar e conhecer a diversidade faunística a ela associada e de se perceber as relações ecológicas entre as espécies que constituem este tipo de ecossistemas. De forma a cobrir as comunidades de macrofauna existentes no local estudaram-se os macroinvertebrados e os peixes presentes em campanhas de amostragem sazonais que decorreram nas épocas do cacimbo e das chuvas, entre 1996 e 1998. No caso dos macroinvertebrados foram inventariados no local ao longo do período de amostragem 163 taxa distribuídos por 10 filos. -

Picayune Strand State Forest Management Plan

Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Noah Valenstein 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399 June 15, 2020 Mr. Keith Rowell Florida Forest Service Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 3125 Conner Boulevard, Room 236 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1650 RE: Picayune Strand State Forest – Lease No. 3927 Dear Mr. Rowell: On June 12, 2020, the Acquisition and Restoration Council (ARC) recommended approval of the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. Therefore, Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services (OES), acting as agent for the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, hereby approves the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. The next management plan update is due June 12, 2030. Pursuant to s. 253.034(5)(a), F.S., each management plan is required to describe both short-term and long-term management goals and include measurable objectives to achieve those goals. Short-term goals shall be achievable within a 2-year planning period, and long-term goals shall be achievable within a 10-year planning period. Upon completion of short-term goals, please submit a signed letter identifying categories, goals, and results with attached methodology to the Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services. Pursuant to s. 259.032(8)(g), F.S., by July 1 of each year, each governmental agency and each private entity designated to manage lands shall report to the Secretary of Environmental Protection, via the Division of State Lands, on the progress of funding, staffing, and resource management of every project for which the agency or entity is responsible. -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

Notice Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions P.O

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY -

Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula, L

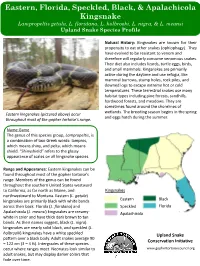

Eastern, Florida, Speckled, Black, & Apalachicola Kingsnake Lampropeltis getula, L. floridana, L. holbrooki, L. nigra, & L. meansi Upland Snake Species Profile Natural History: Kingsnakes are known for their propensity to eat other snakes (ophiophagy). They have evolved to be resistant to venom and therefore will regularly consume venomous snakes. Their diet also includes lizards, turtle eggs, birds, and small mammals. Kingsnakes are primarily active during the daytime and use refugia, like mammal burrows, stump holes, rock piles, and downed logs to escape extreme hot or cold temperatures. These terrestrial snakes use many habitat types including pine forests, sandhills, hardwood forests, and meadows. They are sometimes found around the shorelines of wetlands. The breeding season begins in the spring Eastern kingsnakes (pictured above) occur and eggs hatch during the summer. throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Name Game The genus of this species group, Lampropeltis, is a combination of two Greek words: lampros, which means shiny, and pelta, which means shield. “Shinyshield” refers to the glossy appearance of scales on all kingsnake species. Range and Appearance: Eastern kingsnakes can be found throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Members of the genus can be found throughout the southern United States westward to California, as far north as Maine, and Kingsnakes northwestward to Montana. Eastern (L. getula) kingsnakes are primarily black with white bands Eastern Black across their back. Florida (L. floridana) and Speckled Florida Apalachicola (L. meansi) kingsnakes are creamy- Apalachicola white in color and have thick dark brown to tan bands. As their names suggest, black (L. nigra) kingsnakes are nearly solid black, and speckled (L. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Tertiary and Quaternary Fossil Pyramidelloidean Gastropods of Indonesia

Tertiary and Quaternary fossil pyramidelloidean gastropods of Indonesia E. Robba Robba, E. 2013. Tertiary and Quaternary fossil pyramidelloidean gastropods of Indonesia. Scripta Geo- logica, 144: 1-191, 1 appendix, 1 table, 25 plates. Leiden, April 2013. E. Robba, Università di Milano Bicocca, Dipartimento di Scienze Geologiche e Geotecnologie, Piazza della Scienza 4, 20126 Milano, Italy ([email protected]). Key words – Gastropoda, Pyramidelloidea, taxonomy. The pyramidelloidean gastropods newly collected from one stratigraphic section and two spot localities in the Rembang anticlinorium (Middle Miocene, northeastern Java) are described and those of various ages in the collections of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden are reviewed. A total of 111 species are covered in this paper; another 22 taxa dealt with by previous authors, of which the material was not available, are briefly commented on in an appendix. The “Rembangian” (Middle Miocene) assemblage consists of 89 spe- cies. Four are identified as formerly described species, namelyLeucotina speciosa (Adams), Megastomia regina (Thiele), Exesilla dextra (Saurin) and Exesilla splendida (Martin); 52 are proposed as new; most of the others almost certainly represent previously undescribed species, but cannot be named because of inadequate ma- terial. Parodostomia jogjacartensis (Martin), Parodostomia vandijki (Martin) and Pyramidella nanggulanica Finlay, described from the Eocene deposits of Java, seem to be restricted to that epoch. The Neogene fauna appears to be composed almost entirely of extinct species. Only Leucotina speciosa (Adams), Megastomia regina (Thiele), Longchaeus turritus (Adams), Pyramidella balteata (Adams), Exesilla dextra (Saurin) and Nisiturris alma (Thiele) are still present in modern Indo-West Pacific faunas. Most Neogene species seem to be endemic of the Indonesian Archipelago; relationships with other West Pacific fossil faunas have been noted for only a few taxa. -

Collected During the Dutch CANCAP and MAURITANIA Expeditions in the South-Eastern Part of the North Atlantic Ocean (Part 1)

Pyramidellidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) collected during the Dutch CANCAP and MAURITANIA expeditions in the south-eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean (part 1) CANCAP-project. Contributions, no. 119 J.J. van Aartsen, E. Gittenberger & J. Goud Aartsen, J.J. van, E. Gittenberger & J. Goud. Pyramidellidae (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) collected during the Dutch CANCAP and MAURITANIA expeditions in the south-eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean (part 1). Zool. Verh. Leiden 321, 15.vi.1998:1-57, figs 1-68.— ISSN 0024-1652/ISBN 90-73239-66-4. J.J. van Aartsen, Admiraal Helfrichlaan 33, NL 6952 GB Dieren, The Netherlands. E. Gittenberger, Department of Evertebrata, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 9517, NL 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands (e-mail: [email protected]). J. Goud, Department of Evertebrata, National Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 9517, NL 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands (e-mail: [email protected]). Key words: Pyramidellidae; new species; North Atlantic Ocean. The species of the Pyramidellidae collected during several expeditions in the south-eastern part of the North Atlantic Ocean are listed, with locality data, depth ranges, and notes on nomenclature, system- atics and distribution. The samples classified with the genera Pyramidella, Tiberia, Adelactaeon, Odetta, Folinella, Ondina, Odostomia, Puposyrnola and Eulimella (partly) are dealt with in this paper. In total 64 species are reported from the research area, 32 of which are described as new to science; one nomen novum is introduced. Lectotypes of Aclis tricarinata Watson, 1897, Monoptygma puncturata Smith, 1872, Odetta sulcata de Folin, 1870, and Odostomia sulcifera Smith, 1872, are designated and figured. -

Apalachicola Kingsnake Class: Reptilia

Lampropeltis getula meansi Apalachicola Kingsnake Class: Reptilia. Order: Squamata. Family: Colubridae. Other names: Physical Description: Adults are variable in coloration distinguished from all other Kingsnakes by its overall light dorsal coloration, having either narrow or wide crossbands with considerably lightened interbands, or being non-banded (striped or patternless). Combinations of these basic patterns also occur regularly in the wild. The ventral pattern is also variable, being either bicolor, loose checkerboard with interspersed bicolor scales, or mostly dark. The scales are smooth and there are 21 dorsal scale rows at mid-body. They can grow 10 – 56 inches with a record of 4 ½ feet (56 inches). Kingsnakes are a member of the family of harmless snakes, or Colubridae. This is the largest order of snakes, representing two-thirds of all known snake species. Members of this family are found on all continents except Antarctica, widespread from the Arctic Circle to the southern tips of South America and Africa. All but a handful of species are harmless snakes, not having venom or the ability to deliver toxic saliva through fangs. Most harmless snakes subdue their prey through constriction, striking and seizing small rodents, birds or amphibians and quickly wrapping their body around the prey causing suffocation. While other small species such as the common garter snake lack powers to constrict and feed on only small prey it can overpower. Harmless snakes range in size from 5 inches to nearly 12 feet in length. The largest American species of snake is the indigo snake, a member of this family. It can grow to 11 feet as an adult! Diet in the Wild: Snakes, turtle eggs, lizards, rodents, small birds and their eggs.