Picayune Strand State Forest Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingsnakems RWM

Godley et al. !1 Ecology of the Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) at Rainey Slough, Florida: A Vanished Eden J. STEVE GODLEY1, BRIAN J. HALSTEAD", AND ROY W. MCDIARMID# $Cardno, 3905 Crescent Park Drive, Riverview, FL, 33578, USA "U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Dixon Field Station, 800 Business Park Drive, Suite D, Dixon, CA, 95620, USA #U.S. Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 111 PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, 20013, USA CORRESPONDENCE: email, [email protected] RRH: ECOLOGY OF KINGSNAKES !1 Godley et al. !2 ABSTRACT: The Eastern Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula) is an important component and predator in herpetofaunal communities, but many of its populations have declined precipitously in the last few decades, particularly in the southeastern USA. Here, we describe an intensive mark–recapture study of L. getula conducted from 1974–1978 in a canal bank–water hyacinth community at Rainey Slough in southern Florida, where we also quantitatively sampled their primary prey, other species of snakes. The best-fit model for L. getula was an open population with a high daily capture probability (0.189) and low apparent annual survival (0.128) that were offset by high recruitment and positive population growth rates, suggesting a high turnover rate in the population. Mean population size varied annually from 11–19 adult kingsnakes with a total predator biomass of 8.20–14.16 kg in each study year. At this site kingsnakes were susceptible to capture mostly in winter and spring, were diurnal, used rodent (Sigmodon hispidus) burrows on canal banks as nocturnal retreats, and emerged from burrows on 0.13–0.26 of the sampling days. -

Dragon Magazine #248

DRAGONS Features The Missing Dragons Richard Lloyd A classic article returns with three new dragons for the AD&D® game. Departments 26 56 Wyrms of the North Ed Greenwood The evil woman Morna Auguth is now The Moor Building a Better Dragon Dragon. Paul Fraser Teaching an old dragon new tricks 74Arcane Lore is as easy as perusing this menu. Robert S. Mullin For priestly 34 dragons ... Dragon Dweomers III. Dragon’s Bestiary 80 Gregory W. Detwiler These Crystal Confusion creatures are the distant Dragon-Kin. Holly Ingraham Everythingand we mean everything 88 Dungeon Mastery youll ever need to know about gems. Rob Daviau If youre stumped for an adventure idea, find one In the News. 40 92Contest Winners Thomas S. Roberts The winners are revealed in Ecology of a Spell The Dragon of Vstaive Peak Design Contest. Ed Stark Columns Theres no exagerration when Vore Lekiniskiy THE WYRMS TURN .............. 4 is called a mountain of a dragon. D-MAIL ....................... 6 50 FORUM ........................ 10 SAGE ADVICE ................... 18 OUT OF CHARACTER ............. 24 Fiction BOOKWYRMs ................... 70 The Quest for Steel CONVENTION CALENDAR .......... 98 Ben Bova DRAGONMIRTH ............... 100 Orion must help a young king find both ROLEPLAYING REVIEWS .......... 104 a weapon and his own courage. KNIGHTS OF THE DINNER TABLE ... 114 TSR PREVIEWS ................. 116 62 PROFILES ..................... 120 Staff Publisher Wendy Noritake Executive Editor Pierce Watters Production Manager John Dunn Editor Dave Gross Art Director Larry Smith Associate Editor Chris Perkins Editorial Assistant Jesse Decker Advertising Sales Manager Bob Henning Advertising Traffic Manager Judy Smitha On the Cover Fred Fields blends fantasy with science fiction in this month's anniversary cover. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

The Watchers in Jewish and Christian Traditions

1 Mesopotamian Elements and the Watchers Traditions Ida Fröhlich Introduction By the time of the exile, early Watchers traditions were written in Aramaic, the vernacular in Mesopotamia. Besides many writings associated with Enoch, several works composed in Aramaic came to light from the Qumran library. They manifest several specific common characteristics concerning their literary genres and content. These are worthy of further examination.1 Several Qumran Aramaic works are well acquainted with historical, literary, and other traditions of the Eastern diaspora, and they contain Mesopotamian and Persian elements.2 Early Enoch writings reflect a solid awareness of certain Mesopotamian traditions.3 Revelations on the secrets of the cosmos given to Enoch during his heavenly voyage reflect the influence of Mesopotamian 1. Characteristics of Aramean literary texts were examined by B.Z. Wacholder, “The Ancient Judeo- Aramaic Literature 500–164 bce: A Classification of Pre-Qumranic Texts,” in Archaeology and History in , JSOTSup8, ed. L.H. Schiffman (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 257–81. the Dead Sea Scrolls 2. The most outstanding example is 4Q242, the Prayer of Nabonidus that suggests knowledge of historical legends on the last Neo-Babylonian king Nabunaid (555–539 bce). On the historical background of the legend see R. Meyer, , SSAW.PH 107, no. 3 (Berlin: Akademie, Das Gebet des Nabonid 1962). 4Q550 uses Persian names and the story reflects the influence of the pattern of the Ahiqar novel; see I. Fröhlich, “Stories from the Persian King’s Court. 4Q550 (4QprESTHARa-f),” . 38 Acta Ant. Hung (1998): 103–14. 3. H. L. Jansen, , Skrifter utgitt av Die Henochgestalt: eine vergleichende religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchung det Norske videnskaps-akademi i Oslo. -

![9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9536/9-the-mystical-bitter-water-trial-text-deleted-969536.webp)

9 the Mystical Bitter Water Trial [Text Deleted]

9 The Mystical Bitter Water Trial [text deleted] 9.1 Golems as Archetypes of the Trial’s Supernaturally Inseminated Seed [text deleted] 9.2 Lilith as the First Sotah [text deleted] 9.3 Lilith and Samael as Animating Forces in Golems [text deleted] 9.4 Azazel as the Seed of Lilith No study of Lilith would be complete without a discussion of the demon Azazel. This is true because several clues in many ancient texts - including the Torah, the Zohar, and the First Book of Enoch - indicate that Azazel was the seed of Lilith. The texts further hint that Azazel was not the product of Lilith mating with any ordinary man, but rather he was the firstborn seed resulting from her illicit mating with Semjaza, the leader of a group of fallen angels called Watchers. As the seed of the Watchers, Azazel was the first born of the Nephilim, a race of powerful angel-man hybrids who nearly pushed ordinary mankind to extinction before the flood. But Azazel was much more than just a powerful Nephilim. Regular Nephilim were the products of the daughters of Adam mating with Watchers. Azazel was the product of Lilith mating with the Watchers. He is thus less human than all, and the most powerful, even more powerful than the Watchers who sired him. Azazel’s role in the Yom Kippur ceremony of Leviticus 16 indicates he is a rival to Messiah and God. This identifies Azazel as the legendary seed of the Serpent of Eden. God declared in his curse against the Serpent that this great seed would bruise the heel of Eve’s promised seed (Messiah), but Eve’s seed in turn would crush the head of the Serpent Lilith and destroy her seed. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology

Orlov Dark Mirrors RELIGIOUS STUDIES Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology Dark Mirrors is a wide-ranging study of two central figures in early Jewish demonology—the fallen angels Azazel and Satanael. Andrei A. Orlov explores the mediating role of these paradigmatic celestial rebels in the development of Jewish demonological traditions from Second Temple apocalypticism to later Jewish mysticism, such as that of the Hekhalot and Shi ur Qomah materials. Throughout, Orlov makes use of Jewish pseudepigraphical materials in Slavonic that are not widely known. Dark Mirrors Orlov traces the origins of Azazel and Satanael to different and competing mythologies of evil, one to the Fall in the Garden of Eden, the other to the revolt of angels in the antediluvian period. Although Azazel and Satanael are initially representatives of rival etiologies of corruption, in later Jewish and Christian demonological lore each is able to enter the other’s stories in new conceptual capacities. Dark Mirrors also examines the symmetrical patterns of early Jewish demonology that are often manifested in these fallen angels’ imitation of the attributes of various heavenly beings, including principal angels and even God himself. Andrei A. Orlov is Associate Professor of Theology at Marquette University. He is the author of several books, including Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha. State University of New York Press www.sunypress.edu Andrei A. Orlov Dark Mirrors Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology Andrei A. Orlov Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2011 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. -

Stewart Ross Noye's Fludde

SG MESSENGER: 14 February 2020, No. 19 www.springgroveschool.co.uk NOYE’S FLUDDE STEWART ROSS The heavy rain and floods are a timely reminder to We are very excited to have local author Stewart everyone that we shall be beginning our preparations for Ross visiting the school on Tuesday 25 February to the community opera performances of Benjamin work with the children. Stewart is a prize-winning Britten’s ‘Noye’s Fludde’ which take place on Friday 24th author of fiction and nonfiction for readers of all and Saturday 25th April (the end of the first week of our ages, with over 300 published titles. Summer term). I do hope that all families have inked these dates into their diaries. The event will be truly You can find out more about him on: memorable combining the efforts and talents of our children with adults and professional musicians. https://www.stewartross.com/ Stewart will be selling a selection of his books at the end of the day. Poster Design Competition for Noye’s Fludde All children are invited to submit a poster design for our performances of ‘Noye’s Fludde’. Simple instructions as follows: A4 landscape picture of Mrs and Mrs Noah, the ark and the animals - colour or black and white Deadline is Friday, 28th February. Please hand in designs to the School Office OPEN MORNING SATURDAY 29 FEBRUARY A message will go out shortly to ask for volunteers from Year 1-Prep 6 to come in on Open Day—Saturday 29 February. Please arrive in school for 9.15am—pick-up is at 12 noon. -

Notice Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions P.O

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY -

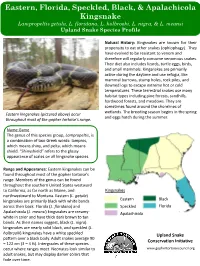

Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula, L

Eastern, Florida, Speckled, Black, & Apalachicola Kingsnake Lampropeltis getula, L. floridana, L. holbrooki, L. nigra, & L. meansi Upland Snake Species Profile Natural History: Kingsnakes are known for their propensity to eat other snakes (ophiophagy). They have evolved to be resistant to venom and therefore will regularly consume venomous snakes. Their diet also includes lizards, turtle eggs, birds, and small mammals. Kingsnakes are primarily active during the daytime and use refugia, like mammal burrows, stump holes, rock piles, and downed logs to escape extreme hot or cold temperatures. These terrestrial snakes use many habitat types including pine forests, sandhills, hardwood forests, and meadows. They are sometimes found around the shorelines of wetlands. The breeding season begins in the spring Eastern kingsnakes (pictured above) occur and eggs hatch during the summer. throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Name Game The genus of this species group, Lampropeltis, is a combination of two Greek words: lampros, which means shiny, and pelta, which means shield. “Shinyshield” refers to the glossy appearance of scales on all kingsnake species. Range and Appearance: Eastern kingsnakes can be found throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Members of the genus can be found throughout the southern United States westward to California, as far north as Maine, and Kingsnakes northwestward to Montana. Eastern (L. getula) kingsnakes are primarily black with white bands Eastern Black across their back. Florida (L. floridana) and Speckled Florida Apalachicola (L. meansi) kingsnakes are creamy- Apalachicola white in color and have thick dark brown to tan bands. As their names suggest, black (L. nigra) kingsnakes are nearly solid black, and speckled (L. -

Bullfrog Creek Management Plan Update, 2015

BULLFROG CREEK AQUATIC RESOURCE PROTECTION AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN UPDATE Prepared for PORT TAMPA BAY ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT 1101 CHANNELSIDE DRIVE TAMPA, FL 33602 By AUDUBON FLORIDA FLORIDA COASTAL ISLANDS SANCTUARIES PROGRAM And LEWIS ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, INC. September 2015 PREFACE This document provides an update to the Bullfrog Creek Aquatic Resource Protection Area (ARPA) Management Plan and has been prepared by Audubon Florida’s Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries (FCIS), Tampa, FL. It updates the earlier plan prepared by FCIS and Lewis Environmental Services, Inc., Salt Springs, FL under contract to the Tampa Port Authority (now Port Tampa Bay) through its Sovereign Lands Management Initiatives Program. Several business affiliations and organizational name transitions and changes have occurred since the original plan was prepared in 1998. In this updated version, we have included the business and institutional names and business affiliations and location names that are currently in use, replacing the outdated names. In addition, we have updated data and survey information relating to the environmental features located within the Bullfrog Creek ARPA and the study area. We are pleased that several of the recommendations presented in the original plan have been implemented in the intervening years by the many organizations and institutions involved in the management of Tampa Bay. For example: - There are currently no sewage residual or septage disposal operations within the Bullfrog Creek watershed. Hillsborough County no longer permits sewage residual disposal within the county’s boundaries. - Year-round boating regulations have been adopted to reduce harm to manatees within the shallower areas of the Bullfrog Creek ARPA. - Shoreline protection/restoration structures have been placed along the highly impacted shorelines of Whiskey Stump and Green Keys, Port Redwing and portions of the Alafia Bank. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L.