Kingsnakems RWM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

Picayune Strand State Forest Management Plan

Ron DeSantis FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF Governor Jeanette Nuñez Environmental Protection Lt. Governor Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Noah Valenstein 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard Secretary Tallahassee, FL 32399 June 15, 2020 Mr. Keith Rowell Florida Forest Service Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services 3125 Conner Boulevard, Room 236 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-1650 RE: Picayune Strand State Forest – Lease No. 3927 Dear Mr. Rowell: On June 12, 2020, the Acquisition and Restoration Council (ARC) recommended approval of the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. Therefore, Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services (OES), acting as agent for the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, hereby approves the Picayune Strand State Forest management plan. The next management plan update is due June 12, 2030. Pursuant to s. 253.034(5)(a), F.S., each management plan is required to describe both short-term and long-term management goals and include measurable objectives to achieve those goals. Short-term goals shall be achievable within a 2-year planning period, and long-term goals shall be achievable within a 10-year planning period. Upon completion of short-term goals, please submit a signed letter identifying categories, goals, and results with attached methodology to the Division of State Lands, Office of Environmental Services. Pursuant to s. 259.032(8)(g), F.S., by July 1 of each year, each governmental agency and each private entity designated to manage lands shall report to the Secretary of Environmental Protection, via the Division of State Lands, on the progress of funding, staffing, and resource management of every project for which the agency or entity is responsible. -

Notice Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions P.O

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY -

Kingsnake Lampropeltis Getula, L

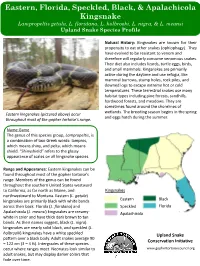

Eastern, Florida, Speckled, Black, & Apalachicola Kingsnake Lampropeltis getula, L. floridana, L. holbrooki, L. nigra, & L. meansi Upland Snake Species Profile Natural History: Kingsnakes are known for their propensity to eat other snakes (ophiophagy). They have evolved to be resistant to venom and therefore will regularly consume venomous snakes. Their diet also includes lizards, turtle eggs, birds, and small mammals. Kingsnakes are primarily active during the daytime and use refugia, like mammal burrows, stump holes, rock piles, and downed logs to escape extreme hot or cold temperatures. These terrestrial snakes use many habitat types including pine forests, sandhills, hardwood forests, and meadows. They are sometimes found around the shorelines of wetlands. The breeding season begins in the spring Eastern kingsnakes (pictured above) occur and eggs hatch during the summer. throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Name Game The genus of this species group, Lampropeltis, is a combination of two Greek words: lampros, which means shiny, and pelta, which means shield. “Shinyshield” refers to the glossy appearance of scales on all kingsnake species. Range and Appearance: Eastern kingsnakes can be found throughout most of the gopher tortoise’s range. Members of the genus can be found throughout the southern United States westward to California, as far north as Maine, and Kingsnakes northwestward to Montana. Eastern (L. getula) kingsnakes are primarily black with white bands Eastern Black across their back. Florida (L. floridana) and Speckled Florida Apalachicola (L. meansi) kingsnakes are creamy- Apalachicola white in color and have thick dark brown to tan bands. As their names suggest, black (L. nigra) kingsnakes are nearly solid black, and speckled (L. -

Bullfrog Creek Management Plan Update, 2015

BULLFROG CREEK AQUATIC RESOURCE PROTECTION AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN UPDATE Prepared for PORT TAMPA BAY ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT 1101 CHANNELSIDE DRIVE TAMPA, FL 33602 By AUDUBON FLORIDA FLORIDA COASTAL ISLANDS SANCTUARIES PROGRAM And LEWIS ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES, INC. September 2015 PREFACE This document provides an update to the Bullfrog Creek Aquatic Resource Protection Area (ARPA) Management Plan and has been prepared by Audubon Florida’s Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries (FCIS), Tampa, FL. It updates the earlier plan prepared by FCIS and Lewis Environmental Services, Inc., Salt Springs, FL under contract to the Tampa Port Authority (now Port Tampa Bay) through its Sovereign Lands Management Initiatives Program. Several business affiliations and organizational name transitions and changes have occurred since the original plan was prepared in 1998. In this updated version, we have included the business and institutional names and business affiliations and location names that are currently in use, replacing the outdated names. In addition, we have updated data and survey information relating to the environmental features located within the Bullfrog Creek ARPA and the study area. We are pleased that several of the recommendations presented in the original plan have been implemented in the intervening years by the many organizations and institutions involved in the management of Tampa Bay. For example: - There are currently no sewage residual or septage disposal operations within the Bullfrog Creek watershed. Hillsborough County no longer permits sewage residual disposal within the county’s boundaries. - Year-round boating regulations have been adopted to reduce harm to manatees within the shallower areas of the Bullfrog Creek ARPA. - Shoreline protection/restoration structures have been placed along the highly impacted shorelines of Whiskey Stump and Green Keys, Port Redwing and portions of the Alafia Bank. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

Venomous Nonvenomous Snakes of Florida

Venomous and nonvenomous Snakes of Florida PHOTOGRAPHS BY KEVIN ENGE Top to bottom: Black swamp snake; Eastern garter snake; Eastern mud snake; Eastern kingsnake Florida is home to more snakes than any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. Since only six species are venomous, and two of those reside only in the northern part of the state, any snake you encounter will most likely be nonvenomous. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission MyFWC.com Florida has an abundance of wildlife, Snakes flick their forked tongues to “taste” their surroundings. The tongue of this yellow rat snake including a wide variety of reptiles. takes particles from the air into the Jacobson’s This state has more snakes than organs in the roof of its mouth for identification. any other state in the Southeast – 44 native species and three nonnative species. They are found in every Fhabitat from coastal mangroves and salt marshes to freshwater wetlands and dry uplands. Some species even thrive in residential areas. Anyone in Florida might see a snake wherever they live or travel. Many people are frightened of or repulsed by snakes because of super- stition or folklore. In reality, snakes play an interesting and vital role K in Florida’s complex ecology. Many ENNETH L. species help reduce the populations of rodents and other pests. K Since only six of Florida’s resident RYSKO snake species are venomous and two of them reside only in the northern and reflective and are frequently iri- part of the state, any snake you en- descent. -

Apalachicola Kingsnake Class: Reptilia

Lampropeltis getula meansi Apalachicola Kingsnake Class: Reptilia. Order: Squamata. Family: Colubridae. Other names: Physical Description: Adults are variable in coloration distinguished from all other Kingsnakes by its overall light dorsal coloration, having either narrow or wide crossbands with considerably lightened interbands, or being non-banded (striped or patternless). Combinations of these basic patterns also occur regularly in the wild. The ventral pattern is also variable, being either bicolor, loose checkerboard with interspersed bicolor scales, or mostly dark. The scales are smooth and there are 21 dorsal scale rows at mid-body. They can grow 10 – 56 inches with a record of 4 ½ feet (56 inches). Kingsnakes are a member of the family of harmless snakes, or Colubridae. This is the largest order of snakes, representing two-thirds of all known snake species. Members of this family are found on all continents except Antarctica, widespread from the Arctic Circle to the southern tips of South America and Africa. All but a handful of species are harmless snakes, not having venom or the ability to deliver toxic saliva through fangs. Most harmless snakes subdue their prey through constriction, striking and seizing small rodents, birds or amphibians and quickly wrapping their body around the prey causing suffocation. While other small species such as the common garter snake lack powers to constrict and feed on only small prey it can overpower. Harmless snakes range in size from 5 inches to nearly 12 feet in length. The largest American species of snake is the indigo snake, a member of this family. It can grow to 11 feet as an adult! Diet in the Wild: Snakes, turtle eggs, lizards, rodents, small birds and their eggs. -

Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (Year 1) - Annex 4: Risk Assessment for Lampropeltis Getula

Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (year 1) - Annex 4: Risk assessment for Lampropeltis getula Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of risk assessments to tackle priority species and enhance prevention Contract No 07.0202/2016/740982/ETU/ENV.D2 Final Report Annex 4: Risk Assessment for Lampropeltis getula (Linnaeus, 1766) November 2017 1 Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of Risk Assessments: Final Report (year 1) - Annex 4: Risk assessment for Lampropeltis getula Risk assessment template developed under the "Study on Invasive Alien Species – Development of risk assessments to tackle priority species and enhance prevention" Contract No 07.0202/2016/740982/ETU/ENV.D2 Based on the Risk Assessment Scheme developed by the GB Non-Native Species Secretariat (GB Non-Native Risk Assessment - GBNNRA) Name of organism: Common kingsnake Lampropeltis getula (Linnaeus, 1766) Author(s) of the assessment: ● Yasmine Verzelen, Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Brussels, Belgium ● Tim Adriaens, Research Institute for Nature and Forest (INBO), Brussels, Belgium ● Riccardo Scalera, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group, Rome, Italy ● Niall Moore, GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), York, Great Britain ● Wolfgang Rabitsch, Umweltbundesamt, Vienna, Austria ● Dan Chapman, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH), Wallingford, Great Britain ● Peter Robertson, Newcastle University, Newcastle, Great Britain Risk Assessment Area: The geographical coverage of the risk assessment is the territory of the European Union (excluding the outermost regions) Peer review 1: Olaf Booy, GB Non-Native Species Secretariat, Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA), York, Great Britain Peer review 2: Ramón Gallo Barneto, Área de Medio Ambiente e Infraestructuras. -

Myakka River State Park

Myakka River State Park Acquisition and Restoration Council Draft Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks June 2018 Executive Summary Lead Agency: Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Common Name of Property: Myakka River State Park Location: Sarasota and Manatee counties Acreage: 37,198.91 Acres Acreage Breakdown Natural Communities Acres Mesic Flatwoods 3766.16 Dry Prairie 14771.03 Mesic Hammock 673.43 Scrubby Flatwoods 182.44 Sinkhole 1.98 Basin Swamp 994.75 Baygall 293.40 Depression Marsh 6788.86 Dome Swamp 8.91 Floodplain Marsh 1181.81 River Floodplain Lake 1218.09 Blackwater Stream 142.57 Developed 75.03 Canal/Ditch 7.70 Artificial Pond 27.00 Abandoned Field 48.96 Abandoned Pasture 565.73 Spoil Area 3.14 Utility Corridor 96.57 Lease/Management Agreement Number: 2324 Use: Single Use Management Responsibilities Agency: Dept. of Environmental Protection, Division of Recreation and Parks Responsibility: Public Outdoor Recreation and Conservation Designated Land Use: Public outdoor recreation and conservation is the designated single use of the property. Sublease: None Encumbrances: None 1 Executive Summary Unique Features Overview: Myakka River State Park is located east of Sarasota in Sarasota and Manatee Counties Access to the park is from Interstate 75, exit 205 (State Road 72); the entrance is 9 miles east on State Road 72/Clark Rd. The park centers around Myakka River. The park was initially acquired in 1934. Currently, the park comprises 37,198.91 acres. The purpose of Myakka River State Park is to preserve the natural beauty, wildlife, and historical features of the property, to serve as an important link in the chain of protected lands in the southern portion of the state, and to provide outstanding outdoor recreation and natural resource interpretation for the benefit of the people of Florida. -

Petition to List 53 Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States As Threatened Or Endangered Species Under the Endangered Species Act

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST 53 AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE UNITED STATES AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED SPECIES UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY JULY 11, 2012 1 Notice of Petition _____________________________________________________________________________ Ken Salazar, Secretary U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Dan Ashe, Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Endangered Species U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1849 C Street NW Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] Nicole Alt, Chief Division of Conservation and Classification, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] Douglas Krofta, Chief Branch of Listing, Endangered Species Program U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Arlington, VA 22203 [email protected] AUTHORS Collette L. Adkins Giese Herpetofauna Staff Attorney Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 339 Circle Pines, MN 55014-0339 [email protected] 2 D. Noah Greenwald Endangered Species Program Director Center for Biological Diversity P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] Tierra Curry Conservation Biologist P.O. Box 11374 Portland, OR 97211-0374 [email protected] PETITIONERS The Center for Biological Diversity. The Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) is a non- profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center is supported by over 375,000 members and on-line activists throughout the United States. -

Lampropeltis Getula (SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE)

ECOLOGY, CONSERVATION, AND MORPHOLOGICAL AND MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF THE KINGSNAKE, Lampropeltis getula (SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE) By KENNETH L. KRYSKO A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2001 Copyright 2001 by Kenneth L. Krysko ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to express my greatest appreciation to my parents, Barbara and Len Krysko, for surviving all of my errors as a child, as well as the recent ones. If it were not for them and their outlook on wildlife and the environment I would not have developed such a passion for all biology-related fields. The research conducted as part of my Master of Science in Biology program at Florida International University, Miami, FL (1995), laid the groundwork for parts of this dissertation. It was in Miami that I was first exposed to all of the political and environmental problems in our state, including the many factors that have disrupted the Everglades ecosystem. I wish to thank my committee members at FIU: George H. Dalrymple (chair), Maureen Donnelly, Scott Quackenbush, Kelsey Downum, and Martin Tracey for their guidance and support. I truly thank my PhD committee members at the University of Florida: F. Wayne King (chair), D. Bruce Means, Walter S. Judd, L. Richard Franz, Brian W. Bowen, Raymond R. Carthy, and Joseph C. Shaefer. They have provided me with many different views on school, research and life. I am especially grateful to F. Wayne King, Kent Vliet, and Jon Reiskind for providing me with research and teaching assistantships throughout my graduate studies.