Scrutinizing the Term Social Media Influencer from a Public Perspective and Examining Its Role in the Modern Media Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media Toolkit for Cultural Managers Table of Contents

The European network on cultural management and policy SOCIAL MEDIA TOOLKIT FOR CULTURAL MANAGERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword and Introduction i How Does Marketing Work Online? 7 A Short History of Social Media 12 The Big Social Networks: What Makes Them Unique? 16 What is Social Capital? 30 How to Build Capital in a Social Network 34 How to Tell Good Stories Online 43 Using Online Data to Understand Your Audience 61 The Six Most Frequently Asked Questions 68 Credits 76 FOREWORD Nowadays, audience development organisations adapt to the need to is on top of the agenda of several engage in new and innovative organisations and networks acting ways with audience both to retain in the field of arts and culture in them, to build new audience, Europe and beyond. Audience diversify audiences including development helps European reaching current “non audience”, artistic and cultural professionals and to improve the experience and their work to reach as many for both existing and future people as possible across Europe audience and deepen the and all over the world and extend relationship with them. access to culture works to underrepresented groups. It also However, how to develop, reach seeks to help artistic and cultural and attract new audiences? Introduction i Upstream by involving them in ENCATC joined as associated at the occasion of our online programming, creation or partner the European consortium survey on the utlisation of social crowd-funding. In the process of of the Study on Audience media. This work has allowed us to participatory art. Downstream Development – How to place gather insights on the current through a two-ways dialogue audiences at the centre of cultural practices in Europe in the made possible by several means organisations utilisation of social media and including the use of social media. -

Sources & Data

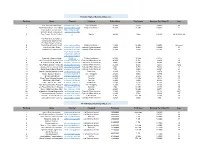

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

Warming up to User-Generated Content

Chicago-Kent College of Law Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship January 2008 Warming Up to User-Generated Content Edward Lee IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/fac_schol Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Warming Up to User-Generated Content, 2008 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1459 (2008). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/fac_schol/358 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. LEE.DOC 9/3/2008 4:50:06 PM WARMING UP TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT Edward Lee* Conventional views of copyright law almost always operate from the “top down.” Copyrights are understood as static and fixed by the Copyright Act. Under this view, copyright holders are at the center of the copyright universe and exercise considerable control over their exclusive rights, with the expectation that others seek prior permission for all uses of copyrighted works outside of a fair use. Though pervasive, this conventional view of copyright is wrong. The Copyright Act is riddled with gray areas and gaps, many of which persist over time, because so few copyright cases are ever filed and the majority of those filed are not resolved through judgment. -

MPC MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER Why My Dad Is Not Dangerously

MPC MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER Why My Dad Is Not Dangerously Regular: Normcore and The Communication of Identity Brittney Brightman Professor Jessica Mudry The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Professional Communication Ryerson University Toronto, Ontario, Canada August 2015 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this Major Research Paper and the accompanying Research Poster. This is a true copy of the MRP and the research poster, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this major research paper and/or poster to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP and/or poster by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP and/or my MRP research poster may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT Background: Using descriptors such as “dangerously regular”, K-Hole’s style movement has been making waves in the fashion industry for its unique, yet familiar Jerry Seinfeld-esque style. This de rigueur ensemble of the 90’s has been revamped into today’s Normcore. A Normcore enthusiast is someone who has mastered the coolness and individuality of fashion and is now interested in blending in. Purpose: The goal of this research was to understand the cultural relevance of the fashion trend Normcore, its subsequent relationship to fashion and identity, as well as what it reveals about contemporary Western culture and the communicative abilities of fashion. -

Social Media Toolkit for Cultural Managers Table of Contents

The European network on cultural management and policy SOCIAL MEDIA TOOLKIT FOR CULTURAL MANAGERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword and Introduction i How Does Marketing Work Online? 7 A Short History of Social Media 12 The Big Social Networks: What Makes Them Unique? 16 What is Social Capital? 30 How to Build Capital in a Social Network 34 How to Tell Good Stories Online 43 Using Online Data to Understand Your Audience 61 The Six Most Frequently Asked Questions 68 Credits 76 FOREWORD Nowadays, audience development organisations adapt to the need to is on top of the agenda of several engage in new and innovative organisations and networks acting ways with audience both to retain in the field of arts and culture in them, to build new audience, Europe and beyond. Audience diversify audiences including development helps European reaching current “non audience”, artistic and cultural professionals and to improve the experience and their work to reach as many for both existing and future people as possible across Europe audience and deepen the and all over the world and extend relationship with them. access to culture works to underrepresented groups. It also However, how to develop, reach seeks to help artistic and cultural and attract new audiences? Introduction i Upstream by involving them in ENCATC joined as associated at the occasion of our online programming, creation or partner the European consortium survey on the utlisation of social crowd-funding. In the process of of the Study on Audience media. This work has allowed us to participatory art. Downstream Development – How to place gather insights on the current through a two-ways dialogue audiences at the centre of cultural practices in Europe in the made possible by several means organisations utilisation of social media and including the use of social media. -

The Edison Project the Edison Project

THE EDISON PROJECT THE EDISON PROJECT Lead Authors: Erin Reilly, Jonathan Taplin, Francesca Marie Smith, Geoffrey Long, Henry Jenkins 18 Havas is the global The Annenberg Innovation research and innovation Lab is a high-energy, center within Havas. In fast-paced Think & Do the offices of Los Angeles, Tank in the Annenberg Seoul, Tel Aviv, Bogota School of Communication and Shanghai. 18 develops and Journalism at the research projects, strategic University of Southern partnerships, and business California. We define opportunities for Havas innovation as a social, and its client portfolio. collaborative process We work to be 18 months involving artists, scientists, ahead at the convergence of humanists and industry media, content, technology, professionals working and data science. We scout together on new problems new talent and startups, and opportunities raised by activate supporting technological and cultural academic research, develop change. Our mission actionable insights, and is to foster real-world facilitate deal-making innovation at the dynamic through local learning intersection of media and expeditions. culture. Copyright 2016. University of Southern California. All rights reserved. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VI THE NEW METRICS + MEASUREMENT: 8 Erin Reilly THE NEW FUNDING + BUSINESS MODELS: 33 Jonathan Taplin and Anjuli Bedi THE NEW SCREENS 51 Francesca Marie Smith THE NEW CREATORS + MAKERS 69 Geoffrey Long, Rachel Joy Victor, Lisa Crawford, Malika Lim, and Juvenal Quiñones, with Ritesh Mehta and Anna Karina Samia CONCLUSION: IMAGINING POSSIBLE FUTURES 92 Henry Jenkins The Edison Project • I INTRODUCTION Thomas Edison invented both the phonograph and the kinetoscope more than 100 years ago. But the business of distributing music and movies hasn’t really changed that much in 100 years. -

The Spider Or the Fly? New Media, Power, and Competing Discussions of Sexual Violence in the Youtube Community

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES The Spider or the Fly? New Media, Power, and Competing Discussions of Sexual Violence in the YouTube Community A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Anthropology by Dalila Isoke Ozier 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Spider or the Fly? New Media, Power, and Competing Discussions of Sexual Violence in the YouTube Community By Dalila Isoke Ozier Master of Arts in Anthropology University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Sherry B. Ortner, Chair In recent years, the advent of new media has enabled public figures to amass devoted followings outside of the context of the traditional media industry. Much of the success of these ―new media celebrities‖ relies on the perceived lack of artificiality in the celebrity‘s public presentation of self. Though the relationship between online content-creators and content-consumers is just as hierarchical as the relationship between traditional celebrities and their fans, the illusion of egalitarianism in digital fandom is maintained by the new media celebrity‘s performance of the ordinary, projecting the image that they are ―just like‖ the fans who idolize them and thereby encouraging a heightened sense of intimacy between fan and creator. Unfortunately, the trust fans have in their idols is regularly abused by some new media celebrities, who use their newfound influence to sexually exploit their predominately adolescent female audience. This research specifically focuses on recent reports of sexual abuse committed by content-creators in the YouTube community, examining how the pseudo-transparent construction of a digital celebrity‘s online identity obfuscates the imbalanced celebrity-fan power dynamic and creates an environment that ii facilitates the celebrity‘s abuse of authority. -

Warming up to User-Generated Content

LEE.DOC 9/3/2008 4:50:06 PM WARMING UP TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT Edward Lee* Conventional views of copyright law almost always operate from the “top down.” Copyrights are understood as static and fixed by the Copyright Act. Under this view, copyright holders are at the center of the copyright universe and exercise considerable control over their exclusive rights, with the expectation that others seek prior permission for all uses of copyrighted works outside of a fair use. Though pervasive, this conventional view of copyright is wrong. The Copyright Act is riddled with gray areas and gaps, many of which persist over time, because so few copyright cases are ever filed and the majority of those filed are not resolved through judgment. In these gray areas, a “top-down” approach simply does not work. Instead, informal copyright practices effectively serve as important gap fillers in our copyright system, operating from the bottom up. The tremendous growth of user-generated content on the Web provides a compelling example of this widespread phenomenon. The informal practices associated with user-generated content make mani- fest three significant features of our copyright system that have es- caped the attention of legal scholars: (i) our copyright system could not function without informal copyright practices; (ii) collectively, us- ers wield far more power in influencing the shape of copyright law than is commonly perceived; and (iii) uncertainty in formal copyright law can lead to the phenomenon of “warming,” in which—unlike chilling—users are emboldened to make unauthorized uses of copy- righted works based on seeing what appears to be an increasingly ac- cepted practice. -

THE POWER of Passion Building Brand Awareness and ENGAGEMENT Among 16–34 YEAR OLDS

YOUTUBE INSIGHTS QUARTERLY INSIGHTS FOR BRANDS FROM GOOGLE AND YOUTUBE UK – OCTOBER 2014 THE POWER OF PASSION BUILDING BRAND AWARENESS AND ENGAGEMENT AMONG 16–34 YEAR OLDS YOUTUBE INSIGHTS OCTOBER 2014, UK 1 The Internet has changed the way 16–34 year olds feed their passions. Whatever interests them the most – sport, cookery, fashion, music – it’s only ever a few clicks away. BUT HOW DO YOU GET THEIR ATTENTION, LET ALONE HOLD IT? YouTube is where this audience goes to watch, discuss and share the things that matter to them. And by harnessing their passions, brands can reach a highly engaged and highly receptive audience – building relationships and driving sales. YOUTUBE INSIGHTS OCTOBER 2014, UK 2 AUDIENCE PAGE 4 CONTENT PAGE 7 IMPACT PAGE 12 YOUTUBE INSIGHTS OCTOBER 2014, UK 3 PART 1 AUDIENCE 12 M 16-34 YEAR OLD INTERNET USERS IN THE UK USE YOUTUBE EVery MONTH Source: ComScore MediaMetrix, average of three months, UK 2014 YOUTUBE INSIGHTS OCTOBER 2014, UK 4 16–34 YEAR OLDS LOVE TO TALK ONLINE, SO ENGAGE WITH THEM Whether it’s through content they’ve created or a video they’re talking about on social media, 16-34 year old YouTube users love to make a noise. That’s good news for brands that they care about, as audiences are eager to give feedback and share their opinions. 78 87 SHARE LINKS TO CONTENT ONLINE COMMENT ON SOMEONE ELSE’s sTATUS, AT LEAST ONCE A MONTH POST OR BLOG AT LEAST ONCE A MONTH 63 GIVE RATINGS ON A PRODUCT, SERVICE OR RESTAURANT ONLINE AT LEAST ONCE A MONTH AND THEY’RE VALUABLE TO BRANDS 59 78 SEARCH YOUTUBE SAY THAT WHEN THEY FIND FOR BRANDS THEY WANT BRANDS THEY LIKE, TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THEY STICK WITH THEM Source for all: YouTube Audience Study UK, 16-34 year old YouTube users, MTM, 2014 YOUTUBE INSIGHTS OCTOBER 2014, UK 5 YOUTUBE IS WHERE 16–34 YEAR OLDS COME TO BE ENTERTAINED Today’s young adults are always connected through a wide range of devices, so they find it easy to stay entertained. -

Digital Desire: Commercial, Moral, and Political Economies of Sex Work and the Internet

Digital Desire: Commercial, Moral, And Political Economies Of Sex Work And The Internet By Copyright 2016 Emily Jean Kennedy Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Joane Nagel ________________________________ Dr. Bob Antonio ________________________________ Dr. Kelly Haesung Chong ________________________________ Dr. Brian Donovan ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: May 4, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Emily Jean Kennedy certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Digital Desire: Commercial, Moral, And Political Economies Of Sex Work And The Internet ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Joane Nagel Date approved: May 4, 2016 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation investigates the relationships among changing public attitudes toward sexuality, the rise of the Internet as a site of commercial sex production and consumption, and public opinion toward and media portrayals of sex workers. In light of increased cultural acceptance of changing sexual practices and identities, I ask, has there been increased acceptance of commercial sex work and sex workers as measured in public opinion, sex workers’ experiences, popular films, and news media portrayals? In order to answer this question, I reviewed and interacted with more than 100 sex work bloggers on Tumblr.com, and conducted -

Writing the Web Series ARONIVES

Byte-Sized TV: Writing the Web Series ARONIVES MASACHUSETTS INSTME By OF TECHNOLOGY Katherine Edgerton MAY 1 4 2013 B.A. Theatre and History, Williams College, 2008 LIBRARIES SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES/WRITING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2013 © Katherine Edgerton, All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: / /I - -11-11 Program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing May 10,2013 Certified by: Heather Hendershot Professor of Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Heather Hendershot Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director of Comparative Media Studies Graduate Program Byte-Sized TV: Writing the Web Series By Katherine Edgerton Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing on May 10, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT Web series or "webisodes" are a transitional storytelling form bridging the production practices of broadcast television and Internet video. Shorter than most television episodes and distributed on online platforms like YouTube, web series both draw on and deviate from traditional TV storytelling strategies. In this thesis, I compare the production and storytelling strategies of "derivative" web series based on broadcast television shows with "original" web series created for the Internet, focusing on the evolution of scripted entertainment content online. -

Grades 9-12 Parent Packet

Grades 9-12 Parent Packet © 2017 Common Sense Media. All rights reserved. www.commonsense.orgwww.commonsense.org1 common sense media 17 Apps and Websites Kids Are Heading to After Facebook Social media apps that let teens do it all — text, chat, meet people, and share their pics and videos — often fly under parents’ radars. By Christine Elgersma Gone are the days of Facebook as a one-stop shop for all social-networking needs. While it may seem more complicated to post photos on Instagram, share casual moments on Snapchat, text on WhatsApp, and check your Twitter feed throughout the day, tweens and teens love the variety. You don’t need to know the ins and outs of all the apps, sites, and terms that are “hot” right now (and frankly, if you did, they wouldn’t be trendy anymore). But knowing the basics — what they are, why they’re popular, and what problems can crop up when they’re not used responsibly — can make the difference between a positive and a negative experience for your kid. Below, we’ve laid out some of the most popular types of apps and websites for teens: texting, microblogging, live-streaming, self-destructing/secret, and chatting/meeting/dating. The more you know about each, the better you’ll be able to communicate with your teen about safe choices. TEXTING APPS GroupMe is an app that doesn’t charge fees or have limits for direct and group messages. Users also can send photos, videos, and calendar links. What parents need to know • It’s for older teens.