Warming up to User-Generated Content

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contenido Generado Por Usuarios (Ugc), Wikies Y Derecho De Autor

contenido generado por usuarios (ugc), wikies y derecho de autor juan * i. introducción La web 2.0 y los modelos colaborativos de creación que con él van de la mano han sido objeto de consideración jurídica por parte de los estudiosos del Derecho. Desde la perspectiva de la propiedad intelectual, el tema no ha sido la excepción. Ello se debe, en gran medida, a la explosión del número de contenidos creados; la superposición del rol de usuario y creador de los contenidos, junto con la gran cantidad y diversidad de los intervinientes en el proceso de creación y el alcance –en muchas ocasiones– global de dicho proceso. El presente artículo pretende contribuir al estudio de la web 2.0 y los modelos creativos a él asociados. Específicamente, pretende inquirir (desde el punto de vista del Derecho de autor) sobre los hiper-documentos creados mediante el software colaborativo tipo Web 2.0 conocido como “wiki”. Para lograr tal objetivo, se estudiarán el concepto de wiki, sus principales características y su función como herramienta tecnológica de creación de valor; las figuras jurídicas que median en la atribución de facultades patrimoniales (y morales) sobre obras protegidas por el Derecho de autor; a qué figura jurídica que media en la atribución de facultades corresponde el contenido generado mediante wiki, y, por último, los problemas que tal adecuación típica representa y las posibles soluciones a dichos problemas. Dicho estudio propondrá dos tipos de problemas y una solución a los mis- mos. Respecto de los problemas, indagará el problema formal de establecer a qué figura de Derecho de autor se adecúan los contenidos creados mediante wiki. -

SHOOT Magazine March/April 2019 Issue

March/April 2019 March/April Chat Room 4 The Road To Emmy Preview Hot Locations 10 4 Spring 2019 DIR Adam McKay Lauren Greenfield Chat Room 18 ECT online.com Series SHOOT ORS Matthew Heineman 8 Ramaa Mosley www. Up-and-Coming Directors 19 Floyd Russ Ridley Scott Spike Jonze Cinematographers & Cameras 22 Top Ten VFX & Animation Chart 26 Top Ten Music Tracks Chart 28 TO GET CONNECTED THE FURTHEST REACHES OF YOUR IMAGINATION ARE CLOSER THAN YOU THINK. With versatile landscapes, experienced film crews and incentivized tax breaks, the only limit to filming in the U.S. Virgin Islands is your imagination. Enjoy up to a 29% tax rebate and up to a 17% transferable tax credit when you film in the USVI. For more opportunities in St.Croix, St. John and St. Thomas, call 340.774.8784 ext. 2243. filmusvi.com DOWNLOAD THE FILM USVI APP: © 2019 U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Tourism USVI19037_9x10.875_SHOOT.indd 1 3/22/19 4:09 PM AGENCY: JWT/Atlanta SPECS: 4C Page Bleed PUB: SHOOT Magazine CLIENT: USVI TRIM: 9” x 10.875” DATE: March/April, 2019 AD#: USVI19037 BLEED: 9.25” x 11.125” HEAD: “The Furthest Reaches of LIVE: 8.5” x 10.375” your Imagination...” Perspectives The Leading Publication For Film, TV & Commercial Production and Post March/April 2019 spot.com.mentary By Robert Goldrich Volume 60 • Number 2 www.SHOOTonline.com EDITORIAL Publisher & Editorial Director Serious Comedy Roberta Griefer 203.227.1699 ext. 701 [email protected] Editor Robert Goldrich Our Up-and-Coming known for its humorous chops, and hope- her feature film, Late Night. -

Steven Stern Matt Naylor

Music by America's Veterans We are proud to announce the release of Unsung Heroes, a collaboration between America’s combat veterans and APM songwriters. Unsung Heroes was born out of the experiences of veteran Richard Casper whose moving story led him to dedicate his life to helping other wounded veterans through the healing power of music through an organization he co-founded, (www.creativets.org). Working together, an American veteran and an APM songwriter write a song inspired by the veteran’s wartime experience and they share songwriting credit and reve- nues from licensing of their music by APM. This first release includes nine powerful songs with both vocal and non-vocal versions. We hope you will be inspired to find a place for these songs in your productions. A percentage of APM’s profits are donated to CreatiVets. Learn more at: www.apmmusic.com/unsungheroes. the writers steven stern The late Steven Stern developed a passion for music at an early age studying music theory and classical guitar at the Peabody Conservatory of Music and earning a degree in Film Music Composition from Berklee College of Music in Boston. Steven began his career with Academy Award-winning composer, Hans Zimmer working on the production of The Lion King, I’ll Do Anything, Renaissance Man, Speed and others. Steven then moved on to score countless film, TV, commercial, and trailer projects and founded his own music library. Steven joined APM in 2011 overseeing our custom music studio in Los Angeles and worked with us until his passing in 2015. -

Youtube and the Vernacular Rhetorics of Web 2.0

i REMEDIATING DEMOCRACY: YOUTUBE AND THE VERNACULAR RHETORICS OF WEB 2.0 Erin Dietel-McLaughlin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Louisa Ha Graduate Faculty Representative Michael Butterworth Lee Nickoson ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor This dissertation examines the extent to which composing practices and rhetorical strategies common to ―Web 2.0‖ arenas may reinvigorate democracy. The project examines several digital composing practices as examples of what Gerard Hauser (1999) and others have dubbed ―vernacular rhetoric,‖ or common modes of communication that may resist or challenge more institutionalized forms of discourse. Using a cultural studies approach, this dissertation focuses on the popular video-sharing site, YouTube, and attempts to theorize several vernacular composing practices. First, this dissertation discusses the rhetorical trope of irreverence, with particular attention to the ways in which irreverent strategies such as new media parody transcend more traditional modes of public discourse. Second, this dissertation discusses three approaches to video remix (collection, Detournement, and mashing) as political strategies facilitated by Web 2.0 technologies, with particular attention to the ways in which these strategies challenge the construct of authorship and the power relationships inherent in that construct. This dissertation then considers the extent to which sites like YouTube remediate traditional rhetorical modes by focusing on the genre of epideictic rhetoric and the ways in which sites like YouTube encourage epideictic practice. Finally, in light of what these discussions reveal in terms of rhetorical practice and democracy in Web 2.0 arenas, this dissertation offers a concluding discussion of what our ―Web 2.0 world‖ might mean for composition studies in terms of theory, practice, and the teaching of writing. -

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

Download Exhibitors List HERE

2017 NAB Show Exhibitor Listing as of 3/29/17 Name Booth [E³] Engstler Elektronik Entwicklung GmbH C8336 1 Beyond, Inc. SL7409 16x9, Inc. known as Band Pro Film & Digital, C10308 Inc. 2018 NAB Show Space Selection N261 24i Media SU11702CM 25/7 Systems known as The Telos Alliance N7724 25-Seven Systems N7724 360 Designs N917VR 360 Systems N3524 360Rize N318VR 3D Storm SL5421 3Play Media SU9524 3Q GmbH C7932 3Way Solutions SA SU10817 4DReplay N5634 4Wall Entertainment C4846 9.Solutions C9143 A.C. Lighting Inc. C11134 AAdynTech C8847 Aaton Digital C2661 AB on Air C2036 ABE Elettronica SRL N8928 AbelCine C8215 Aberdeen Broadcast Services SL11805 Aberdeen LLC SL13913 ABOX42 GmbH SU9821 Absen American Inc. C2146 Accedo SU9205CM Accelerant Media SL13011 Accelerated Media Technologies C3636, OE1309, OE1312 Access Intelligence, LLC SU9625 Accusys Storage Ltd. SL8727 AccuWeather, Inc. SL6816 Acebil/ Eagle America Sales C9718 ACME Portable Machines, Inc. SL4729 Active Storage, LLC SL12116 Actus Digital SU11021 Adder Technology SL11105 Ren Deluxe - L, Ren Deluxe - M, Ren VIP Adobe Systems - C, Ren VIP - D, SL4010 Adorama C9539 Adtec Digital SU7602 Advanced - formerly APG Displays SL15208 Advanced Advertising Theater N6513AD Advanced Media Workflow Association N1431FP (AMWA) Advanced Microwave Components SU6605 Advantage Video Systems SL13318 Advantech Corporation SU11710 Advantech Wireless OE828, SU3821 AEQ, S.A. C3246 Aeson LED Display Technologies SL7624 AFL C12131 AHA Products Group SU12002CM AheadTek C10917 AIC SL13013 AIDA N5432 Air Comm Radio C11243 Airborne Innovations C2660 Airbroad SU7024 Aircode SU6806 AJA Video Systems SL2505 AJT Systems SL9406 Akamai Technologies SL3324 AKITIO SL13417 Aladdin co.,LTD C10418 ALC NetworX N1424 Alcorn McBride Inc N5006 Aldea Solutions SU10121 Aldena Telecomunicazioni s.r.l. -

Social Media Toolkit for Cultural Managers Table of Contents

The European network on cultural management and policy SOCIAL MEDIA TOOLKIT FOR CULTURAL MANAGERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword and Introduction i How Does Marketing Work Online? 7 A Short History of Social Media 12 The Big Social Networks: What Makes Them Unique? 16 What is Social Capital? 30 How to Build Capital in a Social Network 34 How to Tell Good Stories Online 43 Using Online Data to Understand Your Audience 61 The Six Most Frequently Asked Questions 68 Credits 76 FOREWORD Nowadays, audience development organisations adapt to the need to is on top of the agenda of several engage in new and innovative organisations and networks acting ways with audience both to retain in the field of arts and culture in them, to build new audience, Europe and beyond. Audience diversify audiences including development helps European reaching current “non audience”, artistic and cultural professionals and to improve the experience and their work to reach as many for both existing and future people as possible across Europe audience and deepen the and all over the world and extend relationship with them. access to culture works to underrepresented groups. It also However, how to develop, reach seeks to help artistic and cultural and attract new audiences? Introduction i Upstream by involving them in ENCATC joined as associated at the occasion of our online programming, creation or partner the European consortium survey on the utlisation of social crowd-funding. In the process of of the Study on Audience media. This work has allowed us to participatory art. Downstream Development – How to place gather insights on the current through a two-ways dialogue audiences at the centre of cultural practices in Europe in the made possible by several means organisations utilisation of social media and including the use of social media. -

Adams Avenue Street Fair

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, Tfolk, gospel, and bluegrass music news September-October 2004 THIRD ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Vol. 4, No. 1 official program adams ave. street fair - what to see , where to 7 S t a g e s • 8 0 M u s i c a l A c t s • go , how to get there • O s v Welcome ………………3 e h Street Fair Headliners …8 r t Performing Artists …10-19 o 4 o Schedules, Map ………12 0 B 0 s F P t Welcome Mat ………3 o f Mission Statement o a Contributors d r , C Full Circle.. …………4 A r San Diego Music Awards & Lou Curtiss t s s s t e Front Porch …………6 Stag & CeeCee James r 7 A Victoria Robertson C , Acoustic Music San Diego r d a Adams Ave. Street Fair o f o See pp. 8-19 t F Of Note. ……………19 s 0 Victoria Robertson B 0 Joe Morgan o 4 Northstar Session o t r Ramblin’... …………20 h e s Bluegrass Corner v Zen of Recording O José Sinatra Jim McInnes’ Radio Daze Funk • Country • World • Blues • Jazz • Folk • Zydeco • Rockabilly • Latin ‘Round About ....... …22 Sept.-Oct. Music Calendar The Local Seen ……23 nce again, the last weekend in September brings and many more — and continues to draw musicians to San Diego from all over the country who seek fame and exposure. Photo Page us the the largest, most diverse, free music festival Othat may exist in the world today. At the Adams Fun and family-oriented, there is so much to enjoy at the Avenue Street Fair, located between Bancroft Street and 35th Adams Avenue Street Fair: Three beer gardens, carnival rides, Street in Normal Heights, more than 80 different musical acts a pancake breakfast, and more than 400 food and arts and will take the stage over a two-day period: Saturday, September crafts booths. -

SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT Presents a MR. MUDD Production Starring

! ! SUMMIT!ENTERTAINMENT!Presents! ! A!MR.!MUDD!Production! ! ! Starring!Logan!Lerman,!Emma!Watson!and!Ezra!Miller! ! Screenplay!by!Stephen!Chbosky!based!on!his!book! ! Directed!by!Stephen!Chbosky! ! Produced!by!Lianne!Halfon,!Russell!Smith!and!John!Malkovich!! ! Running!Time:!103!minutes! Rated!PG"13! In!Theaters!September!21,!2012!(NY!&!LA)! September!28,!2012!(Expanding)! ! National!Publicity! Eric!Kops!/!Summit!LA!!! 310.255.3007!! [email protected]! Clarissa!Colmenero!/!Summit!NY!! 212.386.6847!! [email protected]! Mike!Rau!/!Summit!LA!!! 310.255.3232!! [email protected]!! ! Regional!Publicity! Sabryna!Phillips!/!Summit!!! 310.309.8420!! [email protected]! ! Online!Publicity! Ryan!Fons!/!Fons!PR!!! 323.445.4763!! [email protected]! THE!PERKS!OF!BEING!A!WALLFLOWER! ! A!sensitive!teenager!learns!to!navigate!the!soaring!highs!and!perilous!lows!of!adolescence!in!The! Perks!of!Being!a!Wallflower,!a!powerful!and!affecting!coming"of"age!story!based!on!the!wildly!popular! young!adult!novel!by!Stephen!Chbosky.!Starring!Logan!Lerman!(Percy!Jackson!and!the!Olympians),!Emma! Watson!(the!Harry!Potter!franchise)!and!Ezra!Miller!(We!Need!to!Talk!About!Kevin,!Another!Happy!Day),! The!Perks!of!Being!a!Wallflower!captures!the!complexities!of!growing!up!with!uncommon!grace,!humor! and!compassion.! It’s!1991!and!academically!precocious,!socially!awkward!Charlie!(Logan!Lerman)!is!a!wallflower,! always!watching!from!the!sidelines,!until!a!pair!of!charismatic!seniors!take!him!under!their!wing.! Beautiful,!free"spirited!Sam!(Emma!Watson)!and!her!fearless!stepbrother,!Patrick!(Ezra!Miller),!shepherd! -

December 2004 Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news January 2005 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 4, No. 4 what’s Nickel Creek: inside Living the Dream Welcome Mat ………3 Mission Statement Contributors Tales from the Trails Full Circle.. …………4 Eugene Vacher Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch …………6 KKSM’s Joan Rubin Tom Boyer Parlor Showcase... …8 Nickel Creek Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze The Highway’s Song... 12 Al Kooper Of Note. ……………13 Griffin House The Taylor Harvey Band Itai ickles the horse chews February 1981, also a home grown Sean and Sara when the surf is good, Rookie Card contentedly in the prodigy raised in the Idylwild moun - and one can feel the excitement in Tom McRae small backyard pasture tains a couple of hours from Vista, it the house as they prepare for one of ‘Round About ....... …14 as the three young - is the mandolin. The three friends are their regular surf safaris to Carlsbad. January Music Calendar sters on the back already creating quite a stir at blue - Mom Karen happily shows the latest porch play their instru - grass festivals and contests. photos of the body board exploits, The Local Seen ……15 ments. It’s peaceful and Life is good in those early days. and Sean and Sara both expound on Photo Page Pbucolic in rural Vista during the mid School at home, church and church the great rides, and “getting pound - 1980s for these three home- activities, surfing, skiing, camping with ed” on the bigger days. -

Sources & Data

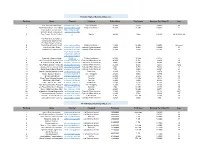

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

The Reasons for the Use of Youtube Among Musicians in India – Using Dependency Theory

The Reasons for the Use of YouTube Among Musicians in India – Using Dependency Theory A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Media Studies by Nrithya Maria Andrews (Reg. No. 1134002) Under the guidance of Dr. SagarikaGolder Assistant Professor DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA STUDIES CHRIST UNIVERSITY BANGALORE, INDIA MARCH 2012 Property of Christ University. Use it for fair pur pose. Give credit to the author by citing properly, if your are using it. Property of Christ University. Use it for fair purpose. Give credit to the author by citing properly, if your are using it. Approval of Dissertation Dissertation titled ‘The reasons for the use of YouTube among musicians in India - using Dependency Theory’ by Nrithya Maria Andrews, Reg. No. 1134002 is approved for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Media Studies. Examiners: 1. ___________________ ___________________ 2. ___________________ ___________________ 3. ___________________ ___________________ Supervisor(s): Dr. Sagarika Golder ___________________ ___________________ Chairman: Mr. John Joseph Kennedy ___________________ ___________________ Date: ___________ (Seal) Place: Christ University Property of Christ University. Use it for fair pu rpose. Give credit to the author by citing properly, if your are using it. i DECLARATION I, Nrithya Maria Andrews, hereby declare that the dissertation, titled ‘The reasons for the use of YouTube among musicians in India- using Dependency Theory’ is a record of original research work undertaken by me for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy in Media Studies. I have completed this study under the supervision of Dr. Sagarika Golder, Assistant Professor, Department of Media Studies I also declare that this dissertation has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associate ship, fellowship or other title.