Online, on the Couch, Or on the Move: the Contours of the Evolving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Social Media Toolkit for Cultural Managers Table of Contents

The European network on cultural management and policy SOCIAL MEDIA TOOLKIT FOR CULTURAL MANAGERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword and Introduction i How Does Marketing Work Online? 7 A Short History of Social Media 12 The Big Social Networks: What Makes Them Unique? 16 What is Social Capital? 30 How to Build Capital in a Social Network 34 How to Tell Good Stories Online 43 Using Online Data to Understand Your Audience 61 The Six Most Frequently Asked Questions 68 Credits 76 FOREWORD Nowadays, audience development organisations adapt to the need to is on top of the agenda of several engage in new and innovative organisations and networks acting ways with audience both to retain in the field of arts and culture in them, to build new audience, Europe and beyond. Audience diversify audiences including development helps European reaching current “non audience”, artistic and cultural professionals and to improve the experience and their work to reach as many for both existing and future people as possible across Europe audience and deepen the and all over the world and extend relationship with them. access to culture works to underrepresented groups. It also However, how to develop, reach seeks to help artistic and cultural and attract new audiences? Introduction i Upstream by involving them in ENCATC joined as associated at the occasion of our online programming, creation or partner the European consortium survey on the utlisation of social crowd-funding. In the process of of the Study on Audience media. This work has allowed us to participatory art. Downstream Development – How to place gather insights on the current through a two-ways dialogue audiences at the centre of cultural practices in Europe in the made possible by several means organisations utilisation of social media and including the use of social media. -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Právnická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity Právo Informačních A

Právnická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity Právo informačních a komunikačních technologií Ústav práva a technologií Rigorózní práce Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých František Kasl 2019 2 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem rigorózní práci na téma: „Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých“ zpracoval sám. Veškeré prameny a zdroje informací, které jsem použil k sepsání této práce, byly citovány v poznámkách pod čarou a jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. ……………………….. František Kasl Právní stav byl v této práci zohledněn ke dni 1. 6. 2019. Překlady anglických termínů a textu v této práci jsou dílem autora práce, pokud není uvedeno jinak. 3 4 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád velmi poděkoval všem, kteří mi s vypracováním této práce pomohli. Děkuji kolegům a kolegyním z Ústavu práva a technologií za podporu a plodné diskuze. Zvláštní poděkování si zaslouží Radim Polčák za nasměrování a validaci nosných myšlenek práce a Pavel Loutocký za důslednou revizi textu práce a podnětné připomínky. Nejvíce pak děkuji své ženě Sabině, jejíž podpora a trpělivost daly prostor této práci vzniknout. 5 6 Abstrakt Rigorózní práce je věnována problematice zásahů do osobnostního práva dětí a mladistvých v prostředí originální tvorby sdílené za pomoci platformy YouTube. Pozornost je těmto věkovým kategoriím věnována především pro jejich zranitelné stádium vývoje individuální i společenské identity. Po úvodní kapitole přichází představení právního rámce ochrany osobnosti a rozbor relevantních aspektů významných pro zbytek práce. Ve třetí kapitole je čtenář seznámen s prostředím sociálních médií a specifiky tzv. platforem pro komunitní sdílení originálního obsahu, mezi které se YouTube řadí. Od této části je již pozornost soustředěna na tvorbu tzv. -

Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability

Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research Volume 8 Article 4 2020 The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability Lea Medina Pepperdine University, [email protected] Eric Reed Pepperdine University, [email protected] Cameron Davis Pepperdine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Medina, Lea; Reed, Eric; and Davis, Cameron (2020) "The 3 P's: Pewdiepie, Popularity, and Profitability," Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/pjcr/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Journal of Communication Research by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 21 The 3 P’s: Pewdiepie, Popularity, & Popularity Lea Medina Written for COM 300: Media Research (Dr. Klive Oh) Introduction Channel is an online prole created on the Felix Arvid Ul Kjellberg—more website YouTube where users can upload their aectionately referred to as Pewdiepie—is original video content to the site. e factors statistically the most successful YouTuber, o his channel that will be explored are his with a net worth o over $15 million and over relationships with the viewers, his personality, 100 million subscribers. With a channel that relationship with his wife, and behavioral has uploaded over 4,000 videos, it becomes patterns. natural to uestion how one person can gain Horton and Wohl’s Parasocial such popularity and prot just by sitting in Interaction eory states that interacting front o a camera. -

Sandrina Costa Pereira Vídeos Virais: Identificação E Análise De

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Comunicação e 2014 Arte Sandrina Vídeos Virais: identificação e análise de Costa caraterísticas dominantes Pereira Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Comunicação Multimédia, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Jorge Trinidad Ferraz de Abreu, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro e coorientação científica do Doutor Pedro Alexandre Ferreira Santos Almeida, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro. Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais e amigos íntimos pelo incentivo e apoio incondicional. o júri presidente Prof. Doutor Telmo Eduardo Miranda Castelão da Silva professor auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Carlos Francisco Lopes Canelas professor adjunto da Escola Superior de Educação, Comunicação e Desporto do Instituto Politécnico da Guarda Prof. Doutor Jorge Trinidad Ferraz de Abreu professor auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro agradecimentos Ao meu orientador, Professor Jorge Ferraz e coorientador Professor Pedro Almeida que me concederam a honra de ser sua orientanda, pelo apoio incondicional, pelas horas perdidas que tiveram ao auxiliar-me e pelos sábios conselhos que me deram durante todo o percurso do mestrado. Aos meus pais que sempre me apoiaram durante toda aminha vida e no meu percurso escolar. Aos meus colegas do departamento que me acompanharam e ajudaram nesta trajetória. Um muito especial obrigado aos colegas da minha turma pelo companheirismo e pelo eterno apoio. Agradecimentos profundos, a minha colega do curso do ramo de Multimédia Interativa, Andreia Pereira, que foi o meu amparo nas horas mais difíceis e que me auxiliou no projeto. -

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA VILNIUS ACADEMY of ARTS TOMAS DAUKŠA Meno Projektas IŠ PUSIAUSVYROS IŠVESTA SISTEMA SU GRĮŽTAMUO

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA VILNIUS ACADEMY OF ARTS TOMAS DAUKŠA Meno projektas IŠ PUSIAUSVYROS IŠVESTA SISTEMA SU GRĮŽTAMUOJU RYŠIU Art Project SYSTEM DERIVED FROM EQUILIBRIUM WITH THE FEEDBACK LOOP Meno doktorantūra, Vaizduojamieji menai, Dailės kryptis (V 002) Art Doctorate, Visual Arts, Fine Arts (V 002) Vilnius, 2019 Meno projektas rengtas Vilniaus dailės akademijoje 2014–2019 metais KŪRYBINĖS DALIES VADOVAS: Prof. Konstantinas Bogdanas Vilniaus dailės akademija, dailė V 002 TIRIAMOSIOS DALIES VADOVĖ: Doc. dr. Agnė Narušytė Vilniaus dailės akademija, humanitariniai mokslai, menotyra H 003 KONSULTANTAS Prof. Henrik B. Andersen Vilniaus dailės akademija, dailė V 002 Meno projektas ginamas Vilniaus dailės akademijoje Meno doktorantūros dailės krypties gynimo taryboje: PIRMININKAS: Dr. Darius Žiūra Vaizduojamieji menai, dailė V 002 NARIAI: Doc. dr. Žygimantas Augustinas Vilniaus dailės akademija, vaizduojamieji menai, dailė V 002 Anders Kreuger Direktorius, Kohta kunsthalė, Helsinkis (Suomija) Dr. Tojana Račiūnaitė Vilniaus dailės akademija, humanitariniai mokslai, menotyra H 003 Prof. dr. Artūras Tereškinas Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, socialiniai mokslai, sociologija S 005 Meno projektas ginamas viešame Meno doktorantūros dailės krypties gynimo tarybos posėdyje 2019 m. lapkričio 29 d. 14 val. Kūrybinių industrijų centre „Pakrantė“ (Vaidilutės g. 79, 10100-Vilnius). Su meno projektu galima susipažinti Lietuvos nacionalinėje Martyno Mažvydo, Vilniaus dailės akademijos bibliotekose. ISBN 978-609-447-326-5 2 The Artistic Research Project -

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues Jesús Muñoz Morcillo1*, Klemens Czurda*, Andrea Geipel**, Caroline Y. Robertson-von Trotha* ABSTRACT: This article provides an overview of the web video production context related to science communication, based on a quantitative analysis of 190 YouTube videos. The authors explore the main characteristics and ongoing strategies of producers, focusing on three topics: professionalism, producer’s gender and age profile, and community building. In the discussion, the authors compare the quantitative results with recently published qualitative research on producers of popular science web videos. This complementary approach gives further evidence on the main characteristics of most popular science communicators on YouTube, it shows a new type of professionalism that surpasses the hitherto existing distinction between User Generated Content (UGC) and Professional Generated Content (PGC), raises gender issues, and questions the participatory culture of science communicators on YouTube. Keywords: Producers of Popular Science Web Videos, Commodification of Science, Gender in Science Communication, Community Building, Professionalism on YouTube Introduction Not very long ago YouTube was introduced as a platform for sharing videos without commodity logic. However, shortly after Google acquired YouTube in 2006, the free exchange of videos gradually shifted to an attention economy ruled by manifold and omnipresent advertising (cf. Jenkins, 2009: 120). YouTube has meanwhile become part of our everyday experience, of our “being in the world” (Merleau Ponty) with all our senses, as an active and constitutive dimension of our understanding of life, knowledge, and communication. However, because of the increasing exploitation of private data, some critical voices have arisen arguing against the production and distribution of free content and warning of the negative consequences for content quality and privacy (e.g., Keen, 2007; Welzer, 2016). -

Sources & Data

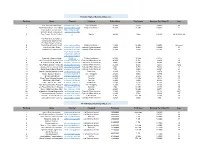

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt -

The Power of You in Youtube

HA RNESSING THE POWER OF " YOU" IN YouTube How just one word - "YOU" - can double your YouTube viewership Writ t en and Researched by Dane Golden and Phil St arkovich a st udy by and .com HARNESSING THE POWER OF "YOU" IN YOUTUBE - A TUBEBUDDY/ HEY.COM STUDY - Published Feb. 7, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HINT: IT'S NOT ME, IT'S "YOU" various ways during the first 30 platform. But it's more likely that "you" is seconds versus videos that did not say a measurable result of videos that are This study is all about YouTube and "YOU." "you" at all in that period. focused on engaging the audience rather than only talking about the subject of the After extensive research, we've found that saying These findings show a clear advantage videos. YouTube is a personal, social video the word "you" just once in the first 5 seconds of for videos that begin with a phrase platform, and the channels that recognize a YouTube video can increase overall views by such as: "Today I'm going to show you and utilize this factor tend to do better. 66%. And views can increase by 97% - essentially how to improve your XYZ." doubling the viewcount - if "you" is said twice in Importantly, this study shows video the first 5 seconds (see table on page 22). While the word "you" is not a silver creators and businesses how to make bullet to success on YouTube, when more money with YouTube. With the word And "you" affects more than YouTube views. We used in context as a part of otherwise "you," YouTubers can double their also learned that simply saying "you" just once in helpful or interesting videos, combined advertising revenue, ecommerce the first 5 seconds of a video is likely to increase with a channel optimization strategy, companies can drive more website clicks, likes per view by approximately 66%, and overall saying "you" has been proven to apps can drive more downloads, and B2B engagements per view by about 68%. -

Trabajo Fin De Grado

Trabajo Fin de Grado El fenómeno youtuber, como influencers y creadores de contenido online The youtuber phenomena, as influencers and online content creators Autor Laura Allué de Magdalena Director José Antonio Gabelas Barroso Grado en Periodismo Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2017 ÍNDICE 1. RESUMEN 2. INTRODUCCIÓN Y JUSTIFICACIÓN DEL TEMA 3. OBJETIVOS E HIPÓTESIS 4. METODOLOGÍA 5. MARCO TEÓRICO 5.1. LOS MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN TRADICIONALES 5.2. EL CONTEXTO DE LA COMUNICACIÓN DIGITAL 5.2.1. EL FACTOR R COMO ELEMENTO EMERGENTE 5.3. LA IMPORTANCIA DE LAS REDES SOCIALES 5.3.1. HÁBITOS DE CONSUMO 5.3.2. YOUTUBE COMO RED SOCIAL 6. CUERPO DEL TRABAJO 6.1. YOUTUBE COMO PORTAL DE VÍDEO ONLINE 6.1.1. ESTADÍSTICAS DE CRECIMIENTO DEL PORTAL 6.1.2. HÁBITOS DE CONSUMO DE VÍDEO EN YOUTUBE 6.1.3. PERFIL DEL CONSUMIDOR 6.1.4. COMPARACIÓN DEL CONSUMO DE YOUTUBE FRENTE A LA TELEVISIÓN 6.1.5. INVERSIÓN PUBLICITARIA EN YOUTUBE Y EN TELEVISIÓN 6.2. LA FIGURA DEL YOUTUBER COMO CREADOR DE CONTENIDO 6.2.1. ¿QUÉ ES UN YOUTUBER? LA PROFESIONALIZACIÓN DE LA PRODUCCIÓN DE VIDEO ONLINE 6.2.2. TEMAS Y GÉNEROS 6.2.3. PRINCIPALES FIGURAS DE YOUTUBE ESPAÑA. 6.2.3.1. ANÁLISIS DEL CANAL “EL RUBIUS OMG” 6.2.3.2. ANÁLISIS DEL CANAL “DULCEIDA” 6.2.3.3. ANÁLISIS DEL CANAL “ROENLARED” 6.3. LA FIGURA DEL YOUTUBER COMO INFLUENCER 6.3.1. INFLUENCIA Y RESPONSABILIDAD PARA CON LAS AUDIENCIAS 6.3.1.1. CASOS DE INFLUENCIA POSITIVA 6.3.1.2. CASOS DE INFLUENCIA NEGATIVA: YOUTUBERS TÓXICOS 6.3.2.