Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Právnická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity Právo Informačních A

Právnická fakulta Masarykovy univerzity Právo informačních a komunikačních technologií Ústav práva a technologií Rigorózní práce Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých František Kasl 2019 2 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem rigorózní práci na téma: „Tvorba YouTuberů prizmatem práva na ochranu osobnosti dětí a mladistvých“ zpracoval sám. Veškeré prameny a zdroje informací, které jsem použil k sepsání této práce, byly citovány v poznámkách pod čarou a jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. ……………………….. František Kasl Právní stav byl v této práci zohledněn ke dni 1. 6. 2019. Překlady anglických termínů a textu v této práci jsou dílem autora práce, pokud není uvedeno jinak. 3 4 Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád velmi poděkoval všem, kteří mi s vypracováním této práce pomohli. Děkuji kolegům a kolegyním z Ústavu práva a technologií za podporu a plodné diskuze. Zvláštní poděkování si zaslouží Radim Polčák za nasměrování a validaci nosných myšlenek práce a Pavel Loutocký za důslednou revizi textu práce a podnětné připomínky. Nejvíce pak děkuji své ženě Sabině, jejíž podpora a trpělivost daly prostor této práci vzniknout. 5 6 Abstrakt Rigorózní práce je věnována problematice zásahů do osobnostního práva dětí a mladistvých v prostředí originální tvorby sdílené za pomoci platformy YouTube. Pozornost je těmto věkovým kategoriím věnována především pro jejich zranitelné stádium vývoje individuální i společenské identity. Po úvodní kapitole přichází představení právního rámce ochrany osobnosti a rozbor relevantních aspektů významných pro zbytek práce. Ve třetí kapitole je čtenář seznámen s prostředím sociálních médií a specifiky tzv. platforem pro komunitní sdílení originálního obsahu, mezi které se YouTube řadí. Od této části je již pozornost soustředěna na tvorbu tzv. -

Sandrina Costa Pereira Vídeos Virais: Identificação E Análise De

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Comunicação e 2014 Arte Sandrina Vídeos Virais: identificação e análise de Costa caraterísticas dominantes Pereira Dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Comunicação Multimédia, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Jorge Trinidad Ferraz de Abreu, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro e coorientação científica do Doutor Pedro Alexandre Ferreira Santos Almeida, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro. Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais e amigos íntimos pelo incentivo e apoio incondicional. o júri presidente Prof. Doutor Telmo Eduardo Miranda Castelão da Silva professor auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Carlos Francisco Lopes Canelas professor adjunto da Escola Superior de Educação, Comunicação e Desporto do Instituto Politécnico da Guarda Prof. Doutor Jorge Trinidad Ferraz de Abreu professor auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro agradecimentos Ao meu orientador, Professor Jorge Ferraz e coorientador Professor Pedro Almeida que me concederam a honra de ser sua orientanda, pelo apoio incondicional, pelas horas perdidas que tiveram ao auxiliar-me e pelos sábios conselhos que me deram durante todo o percurso do mestrado. Aos meus pais que sempre me apoiaram durante toda aminha vida e no meu percurso escolar. Aos meus colegas do departamento que me acompanharam e ajudaram nesta trajetória. Um muito especial obrigado aos colegas da minha turma pelo companheirismo e pelo eterno apoio. Agradecimentos profundos, a minha colega do curso do ramo de Multimédia Interativa, Andreia Pereira, que foi o meu amparo nas horas mais difíceis e que me auxiliou no projeto. -

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA VILNIUS ACADEMY of ARTS TOMAS DAUKŠA Meno Projektas IŠ PUSIAUSVYROS IŠVESTA SISTEMA SU GRĮŽTAMUO

VILNIAUS DAILĖS AKADEMIJA VILNIUS ACADEMY OF ARTS TOMAS DAUKŠA Meno projektas IŠ PUSIAUSVYROS IŠVESTA SISTEMA SU GRĮŽTAMUOJU RYŠIU Art Project SYSTEM DERIVED FROM EQUILIBRIUM WITH THE FEEDBACK LOOP Meno doktorantūra, Vaizduojamieji menai, Dailės kryptis (V 002) Art Doctorate, Visual Arts, Fine Arts (V 002) Vilnius, 2019 Meno projektas rengtas Vilniaus dailės akademijoje 2014–2019 metais KŪRYBINĖS DALIES VADOVAS: Prof. Konstantinas Bogdanas Vilniaus dailės akademija, dailė V 002 TIRIAMOSIOS DALIES VADOVĖ: Doc. dr. Agnė Narušytė Vilniaus dailės akademija, humanitariniai mokslai, menotyra H 003 KONSULTANTAS Prof. Henrik B. Andersen Vilniaus dailės akademija, dailė V 002 Meno projektas ginamas Vilniaus dailės akademijoje Meno doktorantūros dailės krypties gynimo taryboje: PIRMININKAS: Dr. Darius Žiūra Vaizduojamieji menai, dailė V 002 NARIAI: Doc. dr. Žygimantas Augustinas Vilniaus dailės akademija, vaizduojamieji menai, dailė V 002 Anders Kreuger Direktorius, Kohta kunsthalė, Helsinkis (Suomija) Dr. Tojana Račiūnaitė Vilniaus dailės akademija, humanitariniai mokslai, menotyra H 003 Prof. dr. Artūras Tereškinas Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, socialiniai mokslai, sociologija S 005 Meno projektas ginamas viešame Meno doktorantūros dailės krypties gynimo tarybos posėdyje 2019 m. lapkričio 29 d. 14 val. Kūrybinių industrijų centre „Pakrantė“ (Vaidilutės g. 79, 10100-Vilnius). Su meno projektu galima susipažinti Lietuvos nacionalinėje Martyno Mažvydo, Vilniaus dailės akademijos bibliotekose. ISBN 978-609-447-326-5 2 The Artistic Research Project -

Native Content on Social: What Works and What Doesn’T? a Few Questions…

TEXAS PRESS ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE @DALEBLASINGAME NATIVE CONTENT ON SOCIAL: WHAT WORKS AND WHAT DOESN’T? A FEW QUESTIONS… “If we are not prepared to go and search for the audience wherever they live, we will lose.” – ISAAC LEE, PRESIDENT OF NEWS AND DIGITAL FOR UNIVISION AND CEO OF FUSION Photo: ISOJ HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? *but it is possible HOW CAN NEWSROOMS BENEFIT FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS BENEFIT FROM SOCIAL? I’m going to show you five big ways. FACEBOOK INSTANT ARTICLES INSTANT ARTICLES • Now appearing in NewsFeed • 18 publishers: The New York Times, NBC News, The Atlantic, BuzzFeed, National Geographic, Cosmopolitan, Daily Mail, The Huffington Post, Slate, Vox Media, Mic, MTV News, The Washington Post, The Dodo, The Guardian, BBC News, Bild • Load 10x faster than standard web articles INSTANT ARTICLES • Let’s talk money… • 100% of ad revenue news orgs sell on their own • If Facebook sells the ads: It keeps 30 percent of revenue COMING SOON TO INSTANT ARTICLES Billboard, Billy Penn, The Blaze, Bleacher Report, Breitbart, Brit + Co, Business Insider, Bustle, CBS News, CBS Sports, CNET, Complex, Country Living, Cracked, Daily Dot, E! News, Elite Daily, Entertainment Weekly, Gannett, Good Housekeeping, Fox Sports, Harper’s Bazaar, Hollywood Life, Hollywood Reporter, IJ Review, Little Things, Mashable, Mental Floss, mindbodygreen, MLB, MoviePilot, NBA, NY Post, The Onion, Opposing Views, People, Pop Sugar, Rare, Refinery 29, Rolling Stone, Seventeen, TIME, Uproxx, US Magazine, USA Today, Variety, The Verge, The Weather Channel “The first thing we’re seeing is that people are more likely to share these articles, compared to articles on the mobile web, because Instant Articles load faster. -

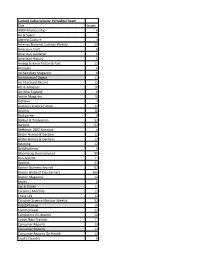

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP Membership 6 Air & Space 7 Altered Couture 4 America National Catholic Weekly 29 American Craft 6 American Gardener 6 American History 6 Analog Science Fiction & Fact 12 Antiques 6 Archaeology Magazine 6 Architectural Digest 12 Architectural Record 12 Art & Antiques 10 Art New England 6 Artists Magazine 10 ArtNews 4 Asimov's Science Fiction 12 Atlantic 10 Backpacker 9 Banker & Tradesman 52 Barrons 52 Beekman 1802 Almanac 4 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Bicycling 12 BirdWatching 6 Bloomberg Businessweek 50 Bon Appetit 11 Booklist 22 Boston Business Journal 52 Boston Globe (7 Day Carrier) 365 Boston Magazine 12 Brides 6 Car & Driver 12 Ceramics Monthly 12 Chess Life 12 Christian Science Monitor Weekly 52 Coastal Living 10 Commonweal 22 Computers In Libraries 10 Conde Nast Traveler 11 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports On Health 12 Cook's Country 6 Cook's Illustrated 6 Cooking Light 12 Cosmopolitan 12 Country Living 10 Discover 10 Domino 4 Down East Magazine 12 Dwell Magazine 6 Easy English News 10 Eating Well 6 Economist 51 Elle 12 Entertainment Weekly 46 Entrepreneur 10 Esquire 10 Family Handyman 8 Fast Company 10 Financial Times 312 Fine Cooking 6 Fine Gardening 6 Fine Homebuilding 8 Fine Woodworking 7 Food & Wine 12 Food Network Magazine 10 Forbes 18 Foreign Affairs 6 Fortune 14 France-Amerique 11 Glamour 16 Good Housekeeping 12 GQ - Gentlemens Quarterly 12 Guardian Weekly 52 Harper's Bazaar 10 Harper's Magazine 12 Harvard Health Letter 12 Harvard Women's Health Watch 12 Health 10 HGTV 10 History Today 12 House Beautiful 10 Inc. -

An Exploratory Study with Major Professional Content Providers in the United Kingdom

Online science videos: an exploratory study with major professional content providers in the United Kingdom M. Carmen Erviti and Erik Stengler Abstract We present an exploratory study of science communication via online video through various UK-based YouTube science content providers. We interviewed five people responsible for eight of the most viewed and subscribed professionally generated content channels. The study reveals that the immense potential of online video as a science communication tool is widely acknowledged, especially regarding the possibility of establishing a dialogue with the audience and of experimenting with different formats. It also shows that some online video channels fully exploit this potential whilst others focus on providing a supplementary platform for other kinds of science communication, such as print or TV. Keywords Popularization of science and technology; Science and media; Visual communication Context Online video is one of the most popular content choices for Internet users. According to Cisco [2014], video traffic was, in terms of data, 66% of all consumer Internet traffic in 2013 and it is predicted to be 79% by 2018. Online video is extensively used for instructional purposes and various authors have analysed this use in recent years [e.g. Pace and Jones, 2009; DeCesare, 2014; Cooper and Higgins, 2015]. Morain and Swarts [2012] proposed a methodology to analyse instructional online video, focussing on sounds, images and texts, the rhetorical work and the information design of a sample of videos. The use of online video within the academic community is also growing as a means of peer-to-peer communication, and Kousha, Thelwall and Abdoli [2012] studied YouTube videos cited in published academic research. -

Australia's Screen Future Is Online: Time to Support Our New Content Creators

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Cunningham, Stuart (2017) Australia’s screen future is online: time to support our new content cre- ators. The Conversation, August, pp. 1-5, 2017. [Article] This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/122374/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https:// theconversation.com/ australias-screen-future-is-online-time-to-support-our-new-content-creators-82638 Academic rigour, journalistic flair Australia’s screen future is online: time to support our new content creators August 21, 2017 5.21am AEST RackaRacka, a sketch channel on YouTube, have been called Australia’s most successful content creators. -

Vlogging the Museum: Youtube As a Tool for Audience Engagement

Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Kris Morrissey Scott Magelssen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Museology ©Copyright 2014 Amanda Dearolph Abstract Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kris Morrissey, Director Museology Each month more than a billion individual users visit YouTube watching over 6 billion hours of video, giving this platform access to more people than most cable networks. The goal of this study is to describe how museums are taking advantage of YouTube as a tool for audience engagement. Three museum YouTube channels were chosen for analysis: the San Francisco Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Field Museum of Natural History. To be included the channel had to create content specifically for YouTube and they were chosen to represent a variety of institutions. Using these three case studies this research focuses on describing the content in terms of its subject matter and alignment with the common practices of YouTube as well as analyzing the level of engagement of these channels achieved based on a series of key performance indicators. This was accomplished with a statistical and content analysis of each channels’ five most viewed videos. The research suggests that content that follows the characteristics and culture of YouTube results in a higher number of views, subscriptions, likes, and comments indicating a higher level of engagement. This also results in a more stable and consistent viewership. -

Solar Cycles: a Comparative 83 Analysis M

Volume 6 Number 2 Apr - Jun 2017 STUDENT JOURNAL OF PHYSICS INTERNATIONAL EDITION INDIAN ASSOCIATION OF PHYSICS TEACHERS ISSN – 2319-3166 STUDENT JOURNAL OF PHYSICS EDITORIAL BOARD INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Editor in Chief H.S. Mani, CMI, Chennai, India ([email protected]) L. Satpathy, Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar, India S. M. Moszkowski, UCLA, USA ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Jogesh C. Pati, SLAC, Stanford, USA ([email protected]) Satya Prakash, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India Chief Editors ([email protected]) S. D. Mahanti, Physics and Astronomy Department, T.V. Ramakrishnan, BHU, Varanasi, India Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mi 48824, USA ([email protected]) ([email protected]) G. Rajasekaran, The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, A.M. Srivastava, Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar, India Chennai, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Ashoke Sen, HRI, Allahabad, India ([email protected]) X. Vinas, Departament d’Estructura i Constituents de la Mat`eria and Institut de Ci`encies del Cosmos, Facultat de F INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD ´ısica, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Danny Caballero, Department of Physics, Michigan State ([email protected]) University, U.S.A. ([email protected]) Gerd Kortemeyer, Joint Professor in Physics & Lyman Briggs College, Michigan State University, U.S.A. Technical Editor ([email protected]) D. Pradhan, ILS, Bhubaneswar, India Bedanga Das Mohanty, NISER, Bhubaneswar, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Prasanta Panigrahi, IISER, Kolkata, India ([email protected]) Web Management K.C. Ajith Prasad, Mahatma Gandhi College, Aditya Prasad Ghosh, IOP, Bhubaneswar, India Thiruvananthapuram, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Ralph Scheicher, Physics Department, University of Uppsala, Sweden ([email protected]) Vijay A. -

The Power of You in Youtube

HA RNESSING THE POWER OF " YOU" IN YouTube How just one word - "YOU" - can double your YouTube viewership Writ t en and Researched by Dane Golden and Phil St arkovich a st udy by and .com HARNESSING THE POWER OF "YOU" IN YOUTUBE - A TUBEBUDDY/ HEY.COM STUDY - Published Feb. 7, 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY HINT: IT'S NOT ME, IT'S "YOU" various ways during the first 30 platform. But it's more likely that "you" is seconds versus videos that did not say a measurable result of videos that are This study is all about YouTube and "YOU." "you" at all in that period. focused on engaging the audience rather than only talking about the subject of the After extensive research, we've found that saying These findings show a clear advantage videos. YouTube is a personal, social video the word "you" just once in the first 5 seconds of for videos that begin with a phrase platform, and the channels that recognize a YouTube video can increase overall views by such as: "Today I'm going to show you and utilize this factor tend to do better. 66%. And views can increase by 97% - essentially how to improve your XYZ." doubling the viewcount - if "you" is said twice in Importantly, this study shows video the first 5 seconds (see table on page 22). While the word "you" is not a silver creators and businesses how to make bullet to success on YouTube, when more money with YouTube. With the word And "you" affects more than YouTube views. We used in context as a part of otherwise "you," YouTubers can double their also learned that simply saying "you" just once in helpful or interesting videos, combined advertising revenue, ecommerce the first 5 seconds of a video is likely to increase with a channel optimization strategy, companies can drive more website clicks, likes per view by approximately 66%, and overall saying "you" has been proven to apps can drive more downloads, and B2B engagements per view by about 68%. -

Narrativa Fílmica E Internet Desconstrução Fílmica E Interatividade

Escola das Artes da Universidade Católica Portuguesa Mestrado em Som e Imagem Narrativa Fílmica e Internet Desconstrução Fílmica e Interatividade Cinema e Audiovisual 2014/2015 Nuno Miguel Rodrigues Meneses Professor Orientador: Carlos Sena Caires Setembro de 2015 Narrativa Fílmica e Internet – Desconstrução Fílmica e Interatividade Dedicatória Aos meus pais que sempre me apoiaram e me deram todas as ferramentas para ser feliz. À minha irmã que desde que nasceu me critica e me faz ser melhor. A todos os meus amigos que me obrigaram a escrever em vez de ver filmes e jogar computador. I Narrativa Fílmica e Internet – Desconstrução Fílmica e Interatividade Agradecimentos O agradecimento maior vai para a minha família, que sempre me apoiou em todos os aspetos. Aperceber-se que se tem um filho que quer ser artista não deve ser fácil, mas eles fizeram-no como se o fosse. À minha família devo tudo. Desde às despesas que causei às emoções que sentimos. Um muito obrigado a todos, em especial à mãe, pai e irmã. Não posso também deixar de agradecer ao professor Carlos Sena Caires que me conduziu na investigação e me fez perceber que a melhor maneira de começar é fazer. Agradeço ainda a todos os outros que estiveram direta ou indiretamente envolvidos nesta dissertação, ou que contribuíram para o seu sucesso. II Narrativa Fílmica e Internet – Desconstrução Fílmica e Interatividade Resumo Nos últimos anos o Cinema tem sofrido inúmeras alterações e evoluções. Quer através do seu desenvolvimento tecnológico, quer através da perceção e interpretação do público das histórias contadas. A tecnologia evolui, assim como a sensibilidade e compreensão artística das plateias.