An Exploratory Study with Major Professional Content Providers in the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

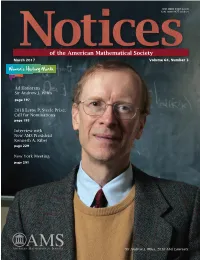

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues Jesús Muñoz Morcillo1*, Klemens Czurda*, Andrea Geipel**, Caroline Y. Robertson-von Trotha* ABSTRACT: This article provides an overview of the web video production context related to science communication, based on a quantitative analysis of 190 YouTube videos. The authors explore the main characteristics and ongoing strategies of producers, focusing on three topics: professionalism, producer’s gender and age profile, and community building. In the discussion, the authors compare the quantitative results with recently published qualitative research on producers of popular science web videos. This complementary approach gives further evidence on the main characteristics of most popular science communicators on YouTube, it shows a new type of professionalism that surpasses the hitherto existing distinction between User Generated Content (UGC) and Professional Generated Content (PGC), raises gender issues, and questions the participatory culture of science communicators on YouTube. Keywords: Producers of Popular Science Web Videos, Commodification of Science, Gender in Science Communication, Community Building, Professionalism on YouTube Introduction Not very long ago YouTube was introduced as a platform for sharing videos without commodity logic. However, shortly after Google acquired YouTube in 2006, the free exchange of videos gradually shifted to an attention economy ruled by manifold and omnipresent advertising (cf. Jenkins, 2009: 120). YouTube has meanwhile become part of our everyday experience, of our “being in the world” (Merleau Ponty) with all our senses, as an active and constitutive dimension of our understanding of life, knowledge, and communication. However, because of the increasing exploitation of private data, some critical voices have arisen arguing against the production and distribution of free content and warning of the negative consequences for content quality and privacy (e.g., Keen, 2007; Welzer, 2016). -

Solar Cycles: a Comparative 83 Analysis M

Volume 6 Number 2 Apr - Jun 2017 STUDENT JOURNAL OF PHYSICS INTERNATIONAL EDITION INDIAN ASSOCIATION OF PHYSICS TEACHERS ISSN – 2319-3166 STUDENT JOURNAL OF PHYSICS EDITORIAL BOARD INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Editor in Chief H.S. Mani, CMI, Chennai, India ([email protected]) L. Satpathy, Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar, India S. M. Moszkowski, UCLA, USA ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Jogesh C. Pati, SLAC, Stanford, USA ([email protected]) Satya Prakash, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India Chief Editors ([email protected]) S. D. Mahanti, Physics and Astronomy Department, T.V. Ramakrishnan, BHU, Varanasi, India Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mi 48824, USA ([email protected]) ([email protected]) G. Rajasekaran, The Institute of Mathematical Sciences, A.M. Srivastava, Institute of Physics, Bhubaneswar, India Chennai, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Ashoke Sen, HRI, Allahabad, India ([email protected]) X. Vinas, Departament d’Estructura i Constituents de la Mat`eria and Institut de Ci`encies del Cosmos, Facultat de F INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD ´ısica, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain Danny Caballero, Department of Physics, Michigan State ([email protected]) University, U.S.A. ([email protected]) Gerd Kortemeyer, Joint Professor in Physics & Lyman Briggs College, Michigan State University, U.S.A. Technical Editor ([email protected]) D. Pradhan, ILS, Bhubaneswar, India Bedanga Das Mohanty, NISER, Bhubaneswar, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Prasanta Panigrahi, IISER, Kolkata, India ([email protected]) Web Management K.C. Ajith Prasad, Mahatma Gandhi College, Aditya Prasad Ghosh, IOP, Bhubaneswar, India Thiruvananthapuram, India ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Ralph Scheicher, Physics Department, University of Uppsala, Sweden ([email protected]) Vijay A. -

Observational Cosmology - 30H Course 218.163.109.230 Et Al

Observational cosmology - 30h course 218.163.109.230 et al. (2004–2014) PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 31 Oct 2013 03:42:03 UTC Contents Articles Observational cosmology 1 Observations: expansion, nucleosynthesis, CMB 5 Redshift 5 Hubble's law 19 Metric expansion of space 29 Big Bang nucleosynthesis 41 Cosmic microwave background 47 Hot big bang model 58 Friedmann equations 58 Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric 62 Distance measures (cosmology) 68 Observations: up to 10 Gpc/h 71 Observable universe 71 Structure formation 82 Galaxy formation and evolution 88 Quasar 93 Active galactic nucleus 99 Galaxy filament 106 Phenomenological model: LambdaCDM + MOND 111 Lambda-CDM model 111 Inflation (cosmology) 116 Modified Newtonian dynamics 129 Towards a physical model 137 Shape of the universe 137 Inhomogeneous cosmology 143 Back-reaction 144 References Article Sources and Contributors 145 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 148 Article Licenses License 150 Observational cosmology 1 Observational cosmology Observational cosmology is the study of the structure, the evolution and the origin of the universe through observation, using instruments such as telescopes and cosmic ray detectors. Early observations The science of physical cosmology as it is practiced today had its subject material defined in the years following the Shapley-Curtis debate when it was determined that the universe had a larger scale than the Milky Way galaxy. This was precipitated by observations that established the size and the dynamics of the cosmos that could be explained by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity. -

Scientists HAVE Written the World's Smallest Periodic Table 5 October 2011

It's true! Scientists HAVE written the world's smallest periodic table 5 October 2011 He is travelling with the creator of the Period Table of Videos, Australian, Brady Haran. Brady said: "We never set out to break a word record, so it's really a pleasant surprise. The main aim of our videos is getting people to think about chemistry. So having our tiny periodic table printed in such a best-seller can only help our cause." More information: www.physorg.com/news/2010-12-s … able-side- human.html (PhysOrg.com) -- The 2012 Guinness World Records has been published and confirms that scientists at The University of Nottingham hold the record for writing the world's smallest periodic table Provided by University of Nottingham . They engraved the table on a strand of hair belonging to Green Chemist Professor Martyn Poliakoff. It took the skills of experts in the University's Nanotechnology and Nanoscience Centre, a beam of accelerated gallium ions and clever imaging to create a table so small that a million of them could be replicated on a typical post- it note. Professor Poliakoff said: "I am delighted. In my wildest nightmares, I have never imagined being in the Guinness World Records, least of all in connection with my hair! The fact that I am is a tribute to the University's Nanotechnology Centre." Professor Poliakoff is one of the stars of the Periodic Table of Videos: www.periodicvideos.com The world's tiniest periodic table was presented to him as a birthday present. His contributions to PTOV have turned him and his colleagues into YouTube stars. -

Senate Responds to Weather Petition

Wednesday, February 15, 2017 Volume CXXXVII, No. 19 • poly.rpi.edu FEATURES Page 9SPORTS Page 12 EDITORIAL Page 4 Ana Faking it until I make Wishnoff it in college Michael Reach out to your Baird loved ones Review of Best Rap Album winner RPI curling ranked best in nation Coloring Book ADMINISTRATION Inclement weather leads to communications mistake Jonathan Caicedo/The Polytechnic SNOWY AND SLICK CONDITIONS SUNDAY EVENING RESULTED in cancellation of morning classes which was reversed Monday morning. Jack Wellhofer it became clear that both the local roads and did include an error, and we apologize for any Senior Reporter campus were still covered in snow. confusion this may have created.” Just before 7 am on Monday, February 13, Part of this frustration culmninated in a peti- ON SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 12, AS HEAVY SNOW FELL email, robocall, and text message notifica- tion that appeared on the RPI Petitions website. across most of the Northeast, notifications tions went out to the Rensselaer community Formal Snow Day Policy reached the required in the form of email, robocall, and text mes- stating Liberal Leave would be in effect and 250 signatures in just a few short hours after sage went out to the Rensselaer community classes would be proceeding as normal. posting, thanks to mass sharing on social media. instating the Liberal Leave policy, allowing This announcement sparked confusion The purpose of the petition was simple: “Once all non-essential staff members an additional and anger among the student body. Many classes are cancelled, do not un-cancel them.” two hours to arrive at work to account for students, assuming that they had the morning As of Tuesday, February 14, Formal Snow conditions on the following Monday. -

Impact Case Study (Ref3b) Institution: the University of Nottingham Unit of Assessment: 9 Title of Case Study: Communicating Research to the Public Through Youtube 1

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: The University of Nottingham Unit of Assessment: 9 Title of case study: Communicating Research to the Public through YouTube 1. Summary of the impact In collaboration with film-maker Brady Haran we have developed the YouTube channel Sixty Symbols to present topics related to research in physics to the wider public. Since the 2009 launch of Sixty Symbols we have posted 212 videos, which have amassed 21.2M views, over 200k comments, over 266k subscribers and a content approval rating of 99.4%, placing Sixty Symbols in the top 0.01% of all YouTube channels. The success of Sixty Symbols led to commissions from Google and STFC for the launch of additional science-focused YouTube channels, and to the formation of the company Periodic Videos Ltd by Brady Haran (2011). Quantitative evidence gathered by management consultants, O’Herlihy & Co, demonstrates Sixty Symbols’ global reach, and significant impact on the attitudes, scientific understanding and career aspirations of its audience. Overall the impact has been on society, culture and creativity through the promotion of public engagement and discourse on science and engineering, and through educational use in schools. 2. Underpinning research The primary motivation within the School for the establishment of Sixty Symbols was to provide a new vehicle for the dissemination of our research using social media, specifically YouTube videos, in order to reach a much wider audience (demographically and geographically) than is possible using conventional approaches -

Emissary | Spring 2021

Spring 2021 EMISSARY M a t h e m a t i c a lSc i e n c e sRe s e a r c hIn s t i t u t e www.msri.org Mathematical Problems in Fluid Dynamics Mihaela Ifrim, Daniel Tataru, and Igor Kukavica The exploration of the mathematical foundations of fluid dynamics began early on in human history. The study of the behavior of fluids dates back to Archimedes, who discovered that any body immersed in a liquid receives a vertical upward thrust, which is equal to the weight of the displaced liquid. Later, Leonardo Da Vinci was fascinated by turbulence, another key feature of fluid flows. But the first advances in the analysis of fluids date from the beginning of the eighteenth century with the birth of differential calculus, which revolutionized the mathematical understanding of the movement of bodies, solids, and fluids. The discovery of the governing equations for the motion of fluids goes back to Euler in 1757; further progress in the nineteenth century was due to Navier and later Stokes, who explored the role of viscosity. In the middle of the twenti- eth century, Kolmogorov’s theory of tur- bulence was another turning point, as it set future directions in the exploration of fluids. More complex geophysical models incorporating temperature, salinity, and ro- tation appeared subsequently, and they play a role in weather prediction and climate modeling. Nowadays, the field of mathematical fluid dynamics is one of the key areas of partial differential equations and has been the fo- cus of extensive research over the years. -

20Th Anniversary 1994-2014 EPSRC 20Th Anniversary CONTENTS 1994-2014

EPSRC 20th Anniversary 1994-2014 EPSRC 20th anniversary CONTENTS 1994-2014 4-9 1994: EPSRC comes into being; 60-69 2005: Green chemistry steps up Peter Denyer starts a camera phone a gear; new facial recognition software revolution; Stephen Salter trailblazes becomes a Crimewatch favourite; modern wave energy research researchers begin mapping the underworld 10-13 1995: From microwave ovens to 70-73 2006: The Silent Aircraft Initiative biomedical engineering, Professor Lionel heralds a greener era in air travel; bacteria Tarassenko’s remarkable career; Professor munch metal, get recycled, emit hydrogen Peter Bruce – batteries for tomorrow 14 74-81 2007: A pioneering approach to 14-19 1996: Professor Alf Adams, prepare against earthquakes and tsunamis; godfather of the internet; Professor Dame beetles inspire high technologies; spin out Wendy Hall – web science pioneer company sells for US$500 million 20-23 1997: The crucial science behind 82-87 2008: Four scientists tackle the world’s first supersonic car; Professor synthetic cells; the 1,000 mph supercar; Malcolm Greaves – oil magnate strategic healthcare partnerships; supercomputer facility is launched 24-27 1998: Professor Kevin Shakesheff – regeneration man; Professor Ed Hinds – 88-95 2009: Massive investments in 20 order from quantum chaos doctoral training; the 175 mph racing car you can eat; rescuing heritage buildings; 28-31 1999: Professor Sir Mike Brady – medical imaging innovator; Unlocking the the battery-free soldier Basic Technologies programme 96-101 2010: Unlocking the -

October 9, 2019

THE NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO ENGINEERING SOCIETY VOLUME 40 ISSUE 12 | WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 9, 2019 Area 51 IW Goes to Cheese Club Should Sleeping be Prioritized Over Studying? Page 6 Page 8 Page 9 facebook.com/TheIronWarrior twitter.com/TheIronWarrior iwarrior.uwaterloo.ca Consider the Hands that Wrote this Letter OSAP Letter Writing Campaign QuinceMedia via Pixabay Student Loans - A Necessary Evil between terms, it’s much easier to see an issue doesn’t concern you the most the goal “to make politicians aware of GABRIELLE KLEMT why people in our faculty might be less is also not helping. In 2017, the former the experiences that students in Ontario 4A GEOLOGICAL reliant on OSAP to pay for school. But Liberal government made updates to are going through”, with an aim to you actually might be missing out on OSAP that included “free” tuition for reinstate funding. The campaign, which savings you could have had. low-income students, meaning some can be found at ousa.ca/signtheletter WUSA VP Education Matt Gerrits students without other access to funding gives students a direct avenue to contact Students take up their pens in protest. has broken the numbers down so we for education received grant money to their local MPP – the more students Seven hundred letters and counting. don’t have to. Engineering students cover the cost of their yearly tuition. from across the province participate, The numbers are growing, the voices likely will save approximately $1,400 Some people might call this socialism, the more MPPs will be aware of their are getting louder, students should not in tuition this academic year. -

The University of Nottingham Nanotechnology and Nanoscience Centre (NNNC)

[4] and analyse the size and morphology of soot The University of Nottingham particles from diesel engines to mention but a few Nanotechnology and examples [5]. Nanoscience Centre (NNNC) The FEGTEM is complemented by the FIBSEM, which is used for the preparation of electron transparent lamellae by site-specific thinning and There are four members of staff, Emily Smith The Nottingham Nanoscience and lift-out using an Omniprobe. The FIBSEM is also (XPS), Dr. Peter Milligan (Business Development), Nanotechnology Centre is located used for the imaging and EDX analysis of a range Dr. Mike Fay (TEM/FIBSEM, EM suite manager) and in the heart of the University of soft and hard materials. In particular, the FIBSEM Dr. Chris Parmenter (FIBSEM/Cryo (SEM/TEM), Park campus and boasts a wide is equipped with a Quorum 2000 PPT cryo-stage, with responsibility for the everyday running of which enables the preservation of delicate hydrated range of microscopes and other the Centre. The NNNC is led by a director and a samples in a near-native state. analytical instruments. The management board of academic advisors. In August Centre’s Dr Chris Parmenter 2013, Prof. Clive Roberts, the Centre’s inaugural Reconstruction of gold nanoparticles in a graphitic nanofibre, by dark field tomography [3]. For example, the CryoFIBSEM has been used for director, became Head of the School of Pharmacy guides us through their catalogue the imaging of diatoms in their native states, being and Prof. Andrei Khlobystov was appointed as the holder for performing electrical measurements; and and highlights some of their of interest to researchers in the Department of a gas-cell reaction holder. -

NEWSLETTER Issue: 485 - November 2019

i “NLMS_485” — 2019/10/25 — 12:08 — page 1 — #1 i i i NEWSLETTER Issue: 485 - November 2019 YAEL NAIM DOWKER GRESHAM’S TEACHING AND GEOMETRY ETHICS IN ERGODIC THEORY PROFESSORS MATHEMATICS i i i i i “NLMS_485” — 2019/10/25 — 12:08 — page 2 — #2 i i i EDITOR-IN-CHIEF COPYRIGHT NOTICE Iain Moatt (Royal Holloway, University of London) News items and notices in the Newsletter may [email protected] be freely used elsewhere unless otherwise stated, although attribution is requested when reproducing whole articles. Contributions to EDITORIAL BOARD the Newsletter are made under a non-exclusive June Barrow-Green (Open University) licence; please contact the author or photog- Tomasz Brzezinski (Swansea University) rapher for the rights to reproduce. The LMS Lucia Di Vizio (CNRS) cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy of Jonathan Fraser (University of St Andrews) information in the Newsletter. Views expressed Jelena Grbic´ (University of Southampton) do not necessarily represent the views or policy Thomas Hudson (University of Warwick) of the Editorial Team or London Mathematical Stephen Huggett Society. Adam Johansen (University of Warwick) Bill Lionheart (University of Manchester) ISSN: 2516-3841 (Print) Mark McCartney (Ulster University) ISSN: 2516-385X (Online) Kitty Meeks (University of Glasgow) DOI: 10.1112/NLMS Vicky Neale (University of Oxford) Susan Oakes (London Mathematical Society) Andrew Wade (Durham University) NEWSLETTER WEBSITE Early Career Content Editor: Vicky Neale The Newsletter is freely available electronically News Editor: Susan Oakes at lms.ac.uk/publications/lms-newsletter. Reviews Editor: Mark McCartney MEMBERSHIP CORRESPONDENTS AND STAFF Joining the LMS is a straightforward process.