Almeta Barrett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

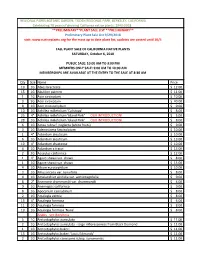

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE ERICACEAE (Heath Family) A family of about 107 genera and 3400 species, primarily shrubs, small trees, and subshrubs, nearly cosmopolitan. The Ericaceae is very important in our area, with a great diversity of genera and species, many of them rather narrowly endemic. Our area is one of the north temperate centers of diversity for the Ericaceae. Along with Quercus and Pinus, various members of this family are dominant in much of our landscape. References: Kron et al. (2002); Wood (1961); Judd & Kron (1993); Kron & Chase (1993); Luteyn et al. (1996)=L; Dorr & Barrie (1993); Cullings & Hileman (1997). Main Key, for use with flowering or fruiting material 1 Plant an herb, subshrub, or sprawling shrub, not clonal by underground rhizomes (except Gaultheria procumbens and Epigaea repens), rarely more than 3 dm tall; plants mycotrophic or hemi-mycotrophic (except Epigaea, Gaultheria, and Arctostaphylos). 2 Plants without chlorophyll (fully mycotrophic); stems fleshy; leaves represented by bract-like scales, white or variously colored, but not green; pollen grains single; [subfamily Monotropoideae; section Monotropeae]. 3 Petals united; fruit nodding, a berry; flower and fruit several per stem . Monotropsis 3 Petals separate; fruit erect, a capsule; flower and fruit 1-several per stem. 4 Flowers few to many, racemose; stem pubescent, at least in the inflorescence; plant yellow, orange, or red when fresh, aging or drying dark brown ...............................................Hypopitys 4 Flower solitary; stem glabrous; plant white (rarely pink) when fresh, aging or drying black . Monotropa 2 Plants with chlorophyll (hemi-mycotrophic or autotrophic); stems woody; leaves present and well-developed, green; pollen grains in tetrads (single in Orthilia). -

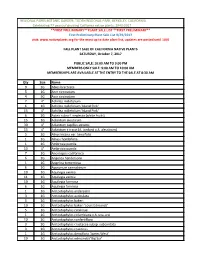

Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies Bracteata 5 1G Acer Circinatum 4 5G Acer

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 77 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2017 **FIRST PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **FIRST PRELIMINARY** First Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2017 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/6 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 7, 2017 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 9 1G Abies bracteata 5 1G Acer circinatum 4 5G Acer circinatum 7 4" Achillea millefolium 6 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 15 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 15 1G Adiantum aleuticum 30 4" Adiantum capillus-veneris 15 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 1 1G Alnus rhombifolia 1 1G Ambrosia pumila 13 4" Ambrosia pumila 7 1G Anemopsis californica 6 1G Angelica hendersonii 1 1G Angelica tomentosa 6 1G Apocynum cannabinum 10 1G Aquilegia eximia 11 1G Aquilegia eximia 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 6 1G Aquilegia formosa 1 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 3 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 10 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 5 1G Arctostaphylos catalinae 1 1G Arctostaphylos columbiana x A. uva-ursi 10 1G Arctostaphylos confertiflora 3 1G Arctostaphylos crustacea subsp. subcordata 3 1G Arctostaphylos cruzensis 1 1G Arctostaphylos densiflora 'James West' 10 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 2 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii 'Big Sur' 22 1G Arctostaphylos edmundsii var. -

Adenostoma Fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos Canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos Virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 5-20-2016 Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) Alison S. Pollack University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pollack, Alison S., "Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species-- Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita)" (2016). Master's Projects and Capstones. 352. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/352 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 This Master's Project Preserving Biodiversity for a Climate Change Future: A Resilience Assessment of Three Bay Area Species--Adenostoma fasciculatum (Chamise), Arctostaphylos canescens (Hoary Manzanita), and Arctostaphylos virgata (Marin Manzanita) by Alison S. Pollack is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Science in Environmental Management at the University of San Francisco Submitted: Received: ................................…………. -

Em4419 1980.Pdf (10.81Mb)

2'75:)Cf EM 4419 W::J7M,' REACTION OF VARIOUS PLANTS TO 2,4-D, MCPA, January 1980 Cor•:1_ 2,4,5-T, SILVEX AND 2,4-DB Compiled by Robert Parker Extension Weed Specialist-Agronomy r-- The chart that follows was taken from several sources and can be used asia· guide to susceptibility of various plants to foliage applications of phenoxy herbicides. In part, this publication was compiled from: · . • Farmers' Bulletin No. 2183 Using Phenoxy Herbicides Effectively, U.S. Department· of Agriculture. • Agricultural Handbook No. 493 Response of Selected Woody Plants in .=-t he United States to Her-. bicides, U.S. Department of Agriculture. ( =-- (" G k • Agricultural Handbook No. 269 Herbicide Manual for Noncropland Weeds, U.S. Department of Agriculture. • Washington State University Weed Control Handbook 1978. Washington State University, Pullman. The chart lists the effects of phenoxy herbicides applied as foliage sprays. Rate of application for 2,4-D, MCPA, 2,4,5-T or silvex is I pound per acre except for woody plants which may require higher rates. Rate of application for 2,4-DB is 2 pounds per acre. The ester formulations are usually best as foliage sprays for killing brush and trees. Some of the woody species are more susceptible to basal or injection/cut surface treatments. The control ratings of the herbicide in the chart are as follows: S = Susceptible These plants usually can be killed with one moderate application of the her bicide at the time when the plant is most susceptible. However, under adverse growth conditions, or as the plants become more mature, they may pass into the Intermediate or even the Resistant group. -

Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon, Based on GLO

HISTORICAL VEGETATION OF CENTRAL SOUTHWEST OREGON, BASED ON GLO SURVEY NOTES Final Report to USDI BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Medford District October 31, 2011 By O. Eugene Hickman and John A. Christy Consulting Rangeland Ecologist Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Retired, USDA - NRCS Portland State University 61851 Dobbin Road PSU – INR, P.O. Box 751 Bend, Oregon 97702 Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 (541, 312-2512) (503, 725-9953) [email protected] [email protected] Suggested citation: Hickman, O. Eugene and John A. Christy. 2011. Historical Vegetation of Central Southwest Oregon Based on GLO Survey Notes. Final Report to USDI Bureau of Land Management. Medford District, Oregon. 124 pp. ______________________________________________________________________________ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 SW OREGON PRE-GLO SURVEY HISTORY ....................................................................................................................... 7 THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE, ITS FUNCTION AND HISTORY........................................................................................... -

Draft Programmatic EIS for Fuels Reduction and Rangeland

NATIONAL SYSTEM OF PUBLIC LANDS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Department of the Interior March 2020 BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Draft Programmatic EIS for Fuels Reduction and Rangeland Restoration in the Great Basin Volume 3: Appendices B through N Estimated Lead Agency Total Costs Associated with Developing and Producing this EIS $2,000,000 The Bureau of Land Management’s multiple-use mission is to sustain the health and productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. The Bureau accomplishes this by managing such activities as outdoor recreation, livestock grazing, mineral development, and energy production, and by conserving natural, historical, cultural, and other resources on public lands. Appendix B. Acronyms, Literature Cited, Glossary B.1 ACRONYMS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Full Phrase ACHP Advisory Council on Historic Preservation AML appropriate management level ARMPA Approved Resource Management Plan Amendment BCR bird conservation region BLM Bureau of Land Management BSU biologically significant unit CEQ Council on Environmental Quality EIS environmental impact statement EPA US Environmental Protection Agency ESA Endangered Species Act ESR emergency stabilization and rehabilitation FIAT Fire and Invasives Assessment Tool FLPMA Federal Land Policy and Management Act FY fiscal year GHMA general habitat management area HMA herd management area IBA important bird area IHMA important habitat management area MBTA Migratory Bird Treaty Act MOU memorandum of understanding MtCO2e metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NHPA National Historic Preservation Act NIFC National Interagency Fire Center NRCS National Resources Conservation Service NRHP National Register of Historic Places NWCG National Wildfire Coordination Group OHMA other habitat management area OHV off-highway vehicle Programmatic EIS for Fuels Reduction and Rangeland Restoration in the Great Basin B-1 B. -

Arctostaphylos Photos Susan Mcdougall Arctostaphylos Andersonii

Arctostaphylos photos Susan McDougall Arctostaphylos andersonii Santa Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos auriculata Mount Diablo Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. bakeri Baker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos bakeri ssp. sublaevis The Cedars Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. canescens Hoary Manzanita Arctostaphylos canescens ssp. sonomensis Sonoma Canescent Manzanita Arctostaphylos catalinae Catalina Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos columbiana Columbia Manzanita Arctostaphylos confertiflora Santa Rosa Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crinita Crinite Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. crustacea Brittleleaf Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. rosei Rose's Manzanita Arctostaphylos crustacea ssp. subcordata Santa Cruz Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos cruzensis Arroyo De La Cruz Manzanita Arctostaphylos densiflora Vine Hill Manzanita Arctostaphylos edmundsii Little Sur Manzanita Arctostaphylos franciscana Franciscan Manzanita Arctostaphylos gabilanensis Gabilan Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. adamsii Adam's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. crassifolia Del Mar Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. cushingiana Cushing's Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. glandulosa Eastwood Manzanita Arctostaphylos glauca Big berry Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hearstiorum Hearst's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hookeri ssp. hookeri Hooker's Manzanita Arctostaphylos hooveri Hoover’s Manzanita Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. howellii Howell's Manzanita Arctostaphylos insularis Island Manzanita Arctostaphylos luciana -

Gottlieb Garden Plants

GOTTLIEB GARDEN Native Plants # Botanical Name Common Name Current SHRUBS 1 Abutilon palmeri Palmer's Indian Mallow (Yellow) 2 Achillea millefolium Common Yarrow - White and 'Island Pink' Yarrow 3 Acmispon glaber var. glaber (fka Lotus scoparius) Common Deerweed, California Broom, Deervetch 4 Adenostoma fasciculatum Chamise 5 Adenostoma fasciculatum 'Nicolas" Nicolas Chamise 6 Agave desertii Desert Agave, Century Plant 7 Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa or Lizard Tail 8 Aquilegia formosa Western Columbine 9 Arabis blepharophylla 'Spring Charm' Rock Cress 10 Archostaphylos 'Winterglow' Winterglow Manzanita 11 Arctostaphylos bakeri Baker's 'Louis Edmunds' Manzanita 12 Arctostaphylos densiflora Vine Hill Mananita 13 Arctostaphylos hookeri Hooker's Manzanita 14 Arctostaphylos 'John Dourley' John Dourley Manzanita 15 Arctostaphylos pajaroensis Pajaro (Paradise) Manzanita 16 Arctostaphylos patula Greenleaf (Bigleaf) Manzanita 17 Arctostaphylos refugioensis Refugio Manzanita 18 Aristida purpurea var. purpurea Purple Threeawn 19 Aristolochia californica California Dutchman's Pipe No 20 Artemesia californica California Sagebrush 'Canyon Grey' 21 Artemesia pycnocephala California Sandhill Sagebrush 'David's Choice', Coastal Sagewort 22 Asclepias fascicularis Narrow-leaf Milkweed No 23 Asclepias speciosa Showy Milkweed 24 Atriplex lentiformis ssp. breweri Quail or Salt Bush 25 Baccharis pilularis ssp. consanguinea Coyote Brush/Chaparral Broom 1356 Laurel Way, Beverly Hills Page 1 of 11 05/17/17 GOTTLIEB GARDEN Native Plants # Botanical Name Common