Umbdlularia Californica (Hook. & Am.) Nutt. California-Laurel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey for Special-Status Vascular Plant Species

SURVEY FOR SPECIAL-STATUS VASCULAR PLANT SPECIES For the proposed Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Project Tehama and Shasta Counties, California Prepared for: Tehama Environmental Solutions 910 Main Street, Suite D Red Bluff, California 96080 Prepared by: Dittes & Guardino Consulting P.O. Box 6 Los Molinos, California 96055 (530) 384-1774 [email protected] Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Improvement Project - Botany Report Sept. 12, 2018 Prepared by: Dittes & Guardino Consulting 1 SURVEY FOR SPECIAL-STATUS VASCULAR PLANT SPECIES Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Project Shasta & Tehama Counties, California T30N, R1W, SE 1/4 Sec. 25, SE1/4 Sec. 24, NE ¼ Sec. 36 of the Shingletown 7.5’ USGS Topographic Quadrangle TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 4 II. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 III. Project Description ............................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. Location .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 V. Methods .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Likely to Have Habitat Within Iras That ALLOW Road

Item 3a - Sensitive Species National Master List By Region and Species Group Not likely to have habitat within IRAs Not likely to have Federal Likely to have habitat that DO NOT ALLOW habitat within IRAs Candidate within IRAs that DO Likely to have habitat road (re)construction that ALLOW road Forest Service Species Under NOT ALLOW road within IRAs that ALLOW but could be (re)construction but Species Scientific Name Common Name Species Group Region ESA (re)construction? road (re)construction? affected? could be affected? Bufo boreas boreas Boreal Western Toad Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Plethodon vandykei idahoensis Coeur D'Alene Salamander Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Rana pipiens Northern Leopard Frog Amphibian 1 No Yes Yes No No Accipiter gentilis Northern Goshawk Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Ammodramus bairdii Baird's Sparrow Bird 1 No No Yes No No Anthus spragueii Sprague's Pipit Bird 1 No No Yes No No Centrocercus urophasianus Sage Grouse Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Falco peregrinus anatum American Peregrine Falcon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Gavia immer Common Loon Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Lanius ludovicianus Loggerhead Shrike Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Oreortyx pictus Mountain Quail Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Otus flammeolus Flammulated Owl Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides albolarvatus White-Headed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Picoides arcticus Black-Backed Woodpecker Bird 1 No Yes Yes No No Speotyto cunicularia Burrowing -

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

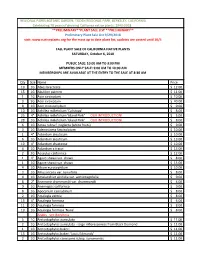

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Torreya Taxifolia

photograph © Abraham Rammeloo Torreya taxifolia produces seeds in 40 Kalmthout Arboretum ABRAHAM RAMMELOO, Curator of the Kalmthout Arboretum, writes about this rare conifer that recently produced seed for the first time. Torreya is a genus of conifers that comprises four to six species that are native to North America and Asia. It is closely related to Taxus and Cephalotaxus and is easily confused with the latter. However, it is relatively easy to distinguish them apart by their leaves. Torreya has needles with, on the underside, two small edges with stomas giving it a green appearance; Cephalotaxus has different rows of stomas, and for this reason the underside is more of a white colour. It is very rare to find Torreya taxifolia in the wild; it is native to a small area in Florida and Georgia. It grows in steep limestone cliffs along the Apalachicola River. These trees come from a warm and humid climate where the temperature in winter occasionally falls below freezing. They grow mainly on north-facing slopes between Fagus grandifolia, Liriodendron tulipifera, Acer barbatum, Liquidambar styraciflua and Quercus alba. They can grow up to 15 to 20 m high. The needles are sharp and pointed and grow in a whorled pattern along the branches. They are 25 to 35 mm long and stay on the tree for three to four years. If you crush them, they give off a strong, sharp odour. The health and reproduction of the adult population of this species suffered INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite Torreya taxifolia ‘Argentea’ growing at Kalmthout Arboretum in Belgium. -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

Conifer Quarterly

Conifer Quarterly Vol. 24 No. 4 Fall 2007 Picea pungens ‘The Blues’ 2008 Collectors Conifer of the Year Full-size Selection Photo Credit: Courtesy of Stanley & Sons Nursery, Inc. CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 1 The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of the American Conifer Society Contents 6 Competitors for the Dwarf Alberta Spruce by Clark D. West 10 The Florida Torreya and the Atlanta Botanical Garden by David Ruland 16 A Journey to See Cathaya argyrophylla by William A. McNamara 19 A California Conifer Conundrum by Tim Thibault 24 Collectors Conifer of the Year 29 Paul Halladin Receives the ACS Annual Award of Merits 30 Maud Henne Receives the Marvin and Emelie Snyder Award of Merit 31 In Search of Abies nebrodensis by Daniel Luscombe 38 Watch Out for that Tree! by Bruce Appeldoorn 43 Andrew Pulte awarded 2007 ACS $1,000 Scholarship by Gerald P. Kral Conifer Society Voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 8 ACS 2008 National Meeting 26 History of the American Conifer Society – Part One 34 2007 National Meeting 42 Letters to the Editor 44 Book Reviews 46 ACS Regional News Vol. 24 No. 4 CONIFER QUARTERLY 1 CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Conifer s I start this letter, we are headed into Afall. In my years of gardening, this has been the most memorable year ever. It started Quarterly with an unusually warm February and March, followed by the record freeze in Fall 2007 Volume 24, No 4 April, and we just broke a record for the number of consecutive days in triple digits. -

Persea Species Restoration in Laurel Wilt Epidemic Areas

Persea Species Restoration in Laurel Wilt Epidemic Areas Photo: Chip Bates Photo: LeRoy Rodgers Melbourne, Florida Ambrosia beetles are typically harmless But, some are causing mass tree mortality Xyleborus glabratus – redbay ambrosia beetle Clonal symbiosis! Raffaelea lauricola - Ophiostomatales Lauraceae are dominant canopy species throughout the tropics • Over 3000 species so taxonomy is poorly understood • Important essential oils: repel insects, perfumes, spices, fragrant wood and www.mobot.org medicine • Agriculturally important: avocado and spices Non-native Lauraceae susceptibility to Raffaelea lauricola Cinnamomum pedunculatum (Japanese cinnamon) Lindera megaphylla 30 days PI (Asia) wilt some, then stop 20 days PI overall tolerant but not resistant Persea podadenia (Mexico) overall susceptible 30 days PI ~35 more species to test Known hosts in the USA Persea borbonia - Redbay Persea palustris – Swamp bay Persea humilis - Silkbay Persea americana - Avocado *Persea indica Cinnamomum camphora – Camphor tree AGprofessional.com Sassafras albidum - Sassafras *Umbellularia californica – California bay laurel Laurus nobilis – European bay laurel *Lindera benzoin - Northern spicebush en.wikipedia.org/ aLindera melissifolia - Pondberry wiki/Sassafras aLitsea aestivalis - Pondspice *Licaria triandra - Gulf licaria *Ocotea coriacea - Lancewood *Persea mexicana – Mexican redbay *artificial fungal inoculation a threatened or endangered Palamedes swallowtail (Papilio palamedes) Laurel Wilt Disease-Widespread and High Mortality Percent redbay -

Conifer Communities of the Santa Cruz Mountains and Interpretive

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA CONIFERS: CONIFER COMMUNITIES OF THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS AND INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE FOR THE UCSC ARBORETUM AND BOTANIC GARDEN A senior internship project in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES by Erika Lougee December 2019 ADVISOR(S): Karen Holl, Environmental Studies; Brett Hall, UCSC Arboretum ABSTRACT: There are 52 species of conifers native to the state of California, 14 of which are endemic to the state, far more than any other state or region of its size. There are eight species of coniferous trees native to the Santa Cruz Mountains, but most people can only name a few. For my senior internship I made a set of ten interpretive signs to be installed in front of California native conifers at the UCSC Arboretum and wrote an associated paper describing the coniferous forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Signs were made using the Arboretum’s laser engraver and contain identification and collection information, habitat, associated species, where to see local stands, and a fun fact or two. While the physical signs remain a more accessible, kid-friendly format, the paper, which will be available on the Arboretum website, will be more scientific with more detailed information. The paper will summarize information on each of the eight conifers native to the Santa Cruz Mountains including localized range, ecology, associated species, and topics pertaining to the species in current literature. KEYWORDS: Santa Cruz, California native plants, plant communities, vegetation types, conifers, gymnosperms, environmental interpretation, UCSC Arboretum and Botanic Garden I claim the copyright to this document but give permission for the Environmental Studies department at UCSC to share it with the UCSC community. -

Phylogeny and Historical Biogeography of Lauraceae

PHYLOGENY Andre'S. Chanderbali,2'3Henk van der AND HISTORICAL Werff,3 and Susanne S. Renner3 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF LAURACEAE: EVIDENCE FROM THE CHLOROPLAST AND NUCLEAR GENOMES1 ABSTRACT Phylogenetic relationships among 122 species of Lauraceae representing 44 of the 55 currentlyrecognized genera are inferredfrom sequence variation in the chloroplast and nuclear genomes. The trnL-trnF,trnT-trnL, psbA-trnH, and rpll6 regions of cpDNA, and the 5' end of 26S rDNA resolved major lineages, while the ITS/5.8S region of rDNA resolved a large terminal lade. The phylogenetic estimate is used to assess morphology-based views of relationships and, with a temporal dimension added, to reconstructthe biogeographic historyof the family.Results suggest Lauraceae radiated when trans-Tethyeanmigration was relatively easy, and basal lineages are established on either Gondwanan or Laurasian terrains by the Late Cretaceous. Most genera with Gondwanan histories place in Cryptocaryeae, but a small group of South American genera, the Chlorocardium-Mezilauruls lade, represent a separate Gondwanan lineage. Caryodaphnopsis and Neocinnamomum may be the only extant representatives of the ancient Lauraceae flora docu- mented in Mid- to Late Cretaceous Laurasian strata. Remaining genera place in a terminal Perseeae-Laureae lade that radiated in Early Eocene Laurasia. Therein, non-cupulate genera associate as the Persea group, and cupuliferous genera sort to Laureae of most classifications or Cinnamomeae sensu Kostermans. Laureae are Laurasian relicts in Asia. The Persea group -

Vegetation Mapping of Eastman and Hensley Lakes and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California

Vegetation Mapping of Eastman and Hensley Lakes and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California By Sara Taylor, Daniel Hastings, Jaime Ratchford, Julie Evens, and Kendra Sikes of the 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento CA, 95816 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Those Who Generously Provided Support and Guidance: Many groups and individuals assisted us in completing this report and the supporting vegetation map/data. First, we expressly thank an anonymous donor who provided financial support in 2010 for this project’s fieldwork and mapping in the southern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We also are thankful of the generous support from California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW, previously Department of Fish and Game) in funding 2008 field survey work in the region. We are indebted to the following additional staff and volunteers of the California Native Plant Society who provided us with field surveying, mission planning, technical GIS, and other input to accomplish this project: Jennifer Buck, Andra Forney, Andrew Georgeades, Brett Hall, Betsy Harbert, Kate Huxster, Theresa Johnson, Claire Muerdter, Eric Peterson, Stu Richardson, Lisa Stelzner, and Aaron Wentzel. To Those Who Provided Land Access: Angela Bradley, Ranger, Eastman Lake, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Bridget Fithian, Mariposa Program Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Chuck Peck, Founder, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Diana Singleton, private landowner Diane Bohna, private landowner Duane Furman, private landowner Jeannette Tuitele-Lewis, Executive Director, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Kristen Boysen, Conservation Project Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Park staff at Hensley Lake, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers i This page has been intentionally left blank. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I.