Conifer Communities of the Santa Cruz Mountains and Interpretive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitat Conservation Plan Outline

Low-Effect Habitat Conservation Plan for Endangered Sandhills Species at the Clements Property, Santa Cruz County California Prepared by: Prepared for: Submitted to: Jodi McGraw, Ph.D. Ron and Natalie Clements Mr. Steve Henry Principal and Ecologist 8225 Ridgeview Drive Field Supervisor Jodi McGraw Consulting Ben Lomond, CA 95005 US Fish and Wildlife Service PO Box 221 2493 Portola Road, Suite B Freedom, CA 95019 Ventura, CA 93003 September 2017 HCP for the Clements Property, Ben Lomond, CA Contents Executive Summary 1 Section 1. Introduction and Background 3 Overview/Background ........................................................................ 3 Permit Holder/Permit Duration ............................................................ 3 Permit Boundary/Covered Lands ........................................................ 3 Species to be Covered by Permit ....................................................... 5 Regulatory Framework ....................................................................... 5 Federal Endangered Species Act ............................................ 5 The Section 10 Process - Habitat Conservation Plan Requirements and Guidelines ................................................. 7 National Environmental Policy Act .......................................... 8 National Historic Preservation Act ...................................................... 8 California Endangered Species Act .................................................... 8 California Environmental Quality Act ................................................. -

Botanical Memo

Appendix C Botanical Memo 10 May 2015 To Willow Creek Community Service District Copy to Patrick Kaspari, Senior Project Manager, GHD Inc. From Cara Scott, Botanist, GHD Inc. Tel 707.443.8326 Subject Special-Status Plant Species Survey and Mapping for Job no. 8410746.05 the Downtown Wastewater Development Project, Willow Creek, CA 1 Introduction On April 10 and May 8, 2015, special-status plant surveys and mapping were conducted for the proposed Downtown Wastewater Development Project in Willow Creek, Humboldt County, California . This survey attempted to identify all vascular plants within the project boundary and to document the presence of special-status plants. The purpose of these surveys was to map presence of special-status plant species and to document the approximate number of individuals and percent cover for each occurrence observed. The results will be used to reduce impacts associated with project construction and to avoid special-status plant populations 1.1 Location The unincorporated community of Willow Creek is located in Humboldt County approximately 45 miles northeast of Eureka, California as shown in Figure 1, Attachment 1. Willow Creek is situated along the Trinity River, which is part of the Klamath River Basin. The Willow Creek Community Services District (WCCSD or District) service area or district boundary is shown on Figure 2 and primarily consists of properties along State Highways 299 and 96. The Pacific Ocean is located approximately 26 miles to the west. The site corresponds to portions of Sections 32 and 33, Township 7 North, Range 5 East on the USGS 7.5 Minute Willow Creek and Salyer quadrangles. -

Landscaping Guide 2.1

Town of Los Altos Hills Landscaping Guide 2.1 Environmental Design and Protection Committee 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW 3 IMPORTANCE OF LANDSCAPING GOALS 3 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 4 WILDFIRE PROTECTIONS 5 LIVING WITH CALIFORNIA OAKS 6 RIPARIAN HABITAT 9 LIVING IN THE HILLS 10 LANDSCAPE MAINTENANCE 14 HERITAGE TREES 15 GARDENS DISPLAYING NATIVE PLANTS 15 HELPFUL REFERENCE BOOKS 15 ONLINE RESOURCES 16 TABLE 1: NATIVE PLANTS 17 TABLE 2: RECOMMENDED PLANTS 20 TABLE 3: INVASIVE PLANTS 20 TABLE 4: FLAMMABLE PLANTS 21 TABLE 5: POISONOUS PLANTS 21 2 OVERVIEW OF LANDSCAPING RECOMMENDATIONS Minimize the visual impact of housing structures with plantings which blend with the natural environment. Use native, drought-tolerant plants. Reduce fire danger by creating a defensible space and managing vegetation. Avoid planting trees which will grow to block neighbors' views, interfere with utility lines, become less effective in screening, or create a wildfire hazard. Minimize or eliminate lawn area; do not use artificial turf. Choose plants appropriate to the topography and adapted to our Sunset Climate Zone 16. Protect native oak trees in construction and landscaping; hand-dig trenches within the drip line (canopy) of native oaks. Do not irrigate or place cobblestones under oaks. Choose plants that are compatible with oaks when planting within an oak canopy. Preserve riparian habitat and vegetation, e.g., willows. Control erosion by minimizing hardscape and using plants which can stabilize steep slopes. Do not use invasive plants; avoid poisonous ones. Consider using deer-resistant plants, or create local deer fencing. Fences should be minimized to allow the free movement of wildlife. -

5 Fagaceae Trees

CHAPTER 5 5 Fagaceae Trees Antoine Kremerl, Manuela Casasoli2,Teresa ~arreneche~,Catherine Bod6n2s1, Paul Sisco4,Thomas ~ubisiak~,Marta Scalfi6, Stefano Leonardi6,Erica ~akker~,Joukje ~uiteveld', Jeanne ~omero-Seversong, Kathiravetpillai Arumuganathanlo, Jeremy ~eror~',Caroline scotti-~aintagne", Guy Roussell, Maria Evangelista Bertocchil, Christian kxerl2,Ilga porth13, Fred ~ebard'~,Catherine clark15, John carlson16, Christophe Plomionl, Hans-Peter Koelewijn8, and Fiorella villani17 UMR Biodiversiti Genes & Communautis, INRA, 69 Route d'Arcachon, 33612 Cestas, France, e-mail: [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita "La Sapienza", Piazza A. Moro 5,00185 Rome, Italy Unite de Recherche sur les Especes Fruitikres et la Vigne, INRA, 71 Avenue Edouard Bourlaux, 33883 Villenave d'Ornon, France The American Chestnut Foundation, One Oak Plaza, Suite 308 Asheville, NC 28801, USA Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA-Forest Service, 23332 Highway 67, Saucier, MS 39574-9344, USA Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, Universitk di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 1lIA, 43100 Parma, Italy Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Alterra Wageningen UR, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, P.O. Box 47,6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA lo Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core Laboratory, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, 1201 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101, -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Oaks (Quercus Spp.): a Brief History

Publication WSFNR-20-25A April 2020 Oaks (Quercus spp.): A Brief History Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care / University Hill Fellow University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources Quercus (oak) is the largest tree genus in temperate and sub-tropical areas of the Northern Hemisphere with an extensive distribution. (Denk et.al. 2010) Oaks are the most dominant trees of North America both in species number and biomass. (Hipp et.al. 2018) The three North America oak groups (white, red / black, and golden-cup) represent roughly 60% (~255) of the ~435 species within the Quercus genus worldwide. (Hipp et.al. 2018; McVay et.al. 2017a) Oak group development over time helped determine current species, and can suggest relationships which foster hybridization. The red / black and white oaks developed during a warm phase in global climate at high latitudes in what today is the boreal forest zone. From this northern location, both oak groups spread together southward across the continent splitting into a large eastern United States pathway, and much smaller western and far western paths. Both species groups spread into the eastern United States, then southward, and continued into Mexico and Central America as far as Columbia. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Today, Mexico is considered the world center of oak diversity. (Hipp et.al. 2018) Figure 1 shows genus, sub-genus and sections of Quercus (oak). History of Oak Species Groups Oaks developed under much different climates and environments than today. By examining how oaks developed and diversified into small, closely related groups, the native set of Georgia oak species can be better appreciated and understood in how they are related, share gene sets, or hybridize. -

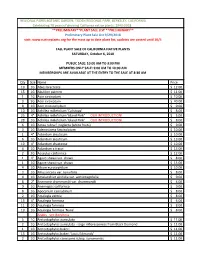

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon

KALMIOPSIS Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon Kalmiopsis leachiana ISSN 1055-419X Volume 20, 2013 &ôùĄÿĂùñü KALMIOPSIS (irteen years, fourteen issues; that is the measure of how long Journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon, ©2013 I’ve been editing Kalmiopsis. (is is longer than I’ve lived in any given house or worked for any employer. I attribute this longevity to the lack of deadlines and time clocks and the almost total freedom to create a journal that is a showcase for our state and society. (ose fourteen issues contained 60 articles, 50 book reviews, and 25 tributes to Fellows, for a total of 536 pages. I estimate about 350,000 words, an accumulation that records the stories of Oregon’s botanists, native )ora, and plant communities. No one knows how many hours, but who counts the hours for time spent doing what one enjoys? All in all, this editing gig has been quite an education for me. I can’t think of a more e*ective and enjoyable way to make new friends and learn about Oregon plants and related natural history than to edit the journal of the Native Plant Society of Oregon. Now it is time for me to move on, but +rst I o*er thanks to those before me who started the journal and those who worked with me: the FEJUPSJBMCPBSENFNCFST UIFBVUIPSTXIPTIBSFEUIFJSFYQFSUJTF UIFSFWJFXFST BOEUIF4UBUF#PBSETXIPTVQQPSUFENZXPSL* especially thank those who will follow me to keep this journal &ôùĄÿĂ$JOEZ3PDIÏ 1I% in print, to whom I also o*er my +les of pending manuscripts, UIFTFSWJDFTPGBOFYQFSJFODFEQBHFTFUUFS BSFMJBCMFQSJOUFSBOE &ôùĄÿĂùñü#ÿñĂô mailing service, and the opportunity of a lifetime: editing our +ne journal, Kalmiopsis. -

Frangula Californica

Frangula californica https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/fracal/all.html#REFE... Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) FEIS Home Page Index of Species Information SPECIES: Frangula californica • Introductory • Distribution and Occurrence • Management Considerations • Botanical and Ecological Characteristics • Fire Ecology • Fire Effects • References California buckthorn. Image ©2012 Jean Pawek, used with permission. Introductory AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: McMurray, Nancy E. 1990. Frangula californica. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/fracal [2021, August 31]. Updates: On 10 July 2018, the common name of this species was changed from: California coffeeberry to: California buckthorn. Images were also added. ABBREVIATION: FRACAL NRCS PLANT CODE [79]: FRCA12 COMMON NAMES: California buckthorn California coffeeberry California false buckthorn hoary coffeeberry 1 of 17 8/31/21, 10:10 AM Frangula californica https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/fracal/all.html#REFE... TAXONOMY: The scientific name of California buckthorn is Frangula californica (Eschsch.) Gray (Rhamnaceae). There are 6 subspecies [37,79,81]: Frangula californica subsp. californica Frangula californica subsp. crassifolia (Jep.) Kartesz & Gandhi Frangula californica subsp. cuspidata (Greene) Kartesz & Gandhi Frangula californica subsp. occidentalis (J. Howell) Kartesz & Gandhi Frangula californica subsp. tomentella (Benth.) Kartesz & Gandhi, hoary coffeeberry Frangula californica subsp. ursina (Greene) Kartesz & Gandhi SYNONYMS: Rhamnus californica Esch. Rhamnus californica subsp. californica Rhamnus californica subsp. occidentalis (J. Howell) C. Wolf Rhamnus tomentella Benth. Rhamnus tomentella Benth. subsp. crassifolia (Jeps.) J.S. Sawyer Rhamnus tomentella Benth. subsp. cuspidata (Greene) J.S. -

Site Assessemnt (PDF)

Site Assessment Report Scotts Valley Hotel SCOTTS VALLEY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA December 29, 2014 Prepared by: On behalf of: Johnson Marigot Consulting, LLC City Ventures, LLC Cameron Johnson Mr. Jason Bernstein 88 North Hill Drive, Suite C 444 Spear Street, Suite 200 Brisbane, California 94005 San Francisco, California 94105 1 Table Of Contents SECTION 1: Environmental Setting ................................................................................... 4 A. Project Location ........................................................................................................................... 4 B. Surrounding Land Use ................................................................................................................ 4 C. Study Area Topography and Hydrology ............................................................................... 4 D. Study Area Soil .............................................................................................................................. 5 E. Vegetation Types .......................................................................................................................... 5 SECTION 2: Methods ............................................................................................................... 7 A. Site Visit .......................................................................................................................................... 7 B. Study Limits .................................................................................................................................. -

Estado Actual De Las Microrreservas De Flora De La Comarca De La Canal De Navarrés”

UNIVERSIDAD POLITECNICA DE VALENCIA ESCUELA POLITE CNICA SUPERIOR DE GANDIA Licenciado en Ciencias Ambientales “Estado Actual de las Microrreservas de Flora de la Comarca de la Canal de Navarrés” TRABAJO FINAL DE CARRERA Autor/es: Maria Amparo Castelló Hernández Director/es: Enrique Sanchis Duato GANDIA, 2013 INDICE 1- INTRODUCCIÓN ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 1.1- Microrreservas ------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.1.1- Definición ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.1.2- Grados de protección de las MRF ------------------------------------------------------------------ 6 1.1.3- Declaración de las MRF --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 1.1.4- ¿Dónde pueden encontrarse las MRF? ----------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.2- Endemismos ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.2.1- Definición ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.2.2- Tipos de endemismos ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.2.3- Grados de endemicidad -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2.4- Origen de los endemismos ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 1.2.5- Fragilidad de los endemismos -

Conifer Quarterly

Conifer Quarterly Vol. 24 No. 4 Fall 2007 Picea pungens ‘The Blues’ 2008 Collectors Conifer of the Year Full-size Selection Photo Credit: Courtesy of Stanley & Sons Nursery, Inc. CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 1 The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of the American Conifer Society Contents 6 Competitors for the Dwarf Alberta Spruce by Clark D. West 10 The Florida Torreya and the Atlanta Botanical Garden by David Ruland 16 A Journey to See Cathaya argyrophylla by William A. McNamara 19 A California Conifer Conundrum by Tim Thibault 24 Collectors Conifer of the Year 29 Paul Halladin Receives the ACS Annual Award of Merits 30 Maud Henne Receives the Marvin and Emelie Snyder Award of Merit 31 In Search of Abies nebrodensis by Daniel Luscombe 38 Watch Out for that Tree! by Bruce Appeldoorn 43 Andrew Pulte awarded 2007 ACS $1,000 Scholarship by Gerald P. Kral Conifer Society Voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 8 ACS 2008 National Meeting 26 History of the American Conifer Society – Part One 34 2007 National Meeting 42 Letters to the Editor 44 Book Reviews 46 ACS Regional News Vol. 24 No. 4 CONIFER QUARTERLY 1 CQ_FALL07_FINAL.qxp:CQ 10/16/07 1:45 PM Page 2 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Conifer s I start this letter, we are headed into Afall. In my years of gardening, this has been the most memorable year ever. It started Quarterly with an unusually warm February and March, followed by the record freeze in Fall 2007 Volume 24, No 4 April, and we just broke a record for the number of consecutive days in triple digits.