04 TEN Group, Report of Meeting 4, Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S:\Aybplan\Bpläne\01-0008Ba\ Ib\01

R N s o o t s s r v . e K t R a r 1 n l . 3 o 1 K 1 J 203 e l 1 i 3 o t s s 1194 l i 5 St.Adelbert- 1 e A n Abzeichnung h 0 a e 54 - Übersichtskartei 1:10e 000 n c n 21 Bebauungsplan 1-8Ba s 1 a 3 1 2 kirche h Garnisons- 4 e t 2 2 K 7 3 2 0 t h 0 6 Koppen- i l 12 3 r l 1 6 2 6 . Kita m e . 4 . A 5 a friedhof 6 2 199 80 H 20 r 1 2 a 5 Spielpl. u - r l t 0 e s m 1 g 44 r Franz-Mett- S 6 t Volkshochschule u 9 . 9 S 1 2 b 5 r platz 9 r 4 1 4 s 5 u noch nicht rechtsverbindlich 0 Sporthalle t . 2 t 1 r t . g s A r r 7 . e 50 6 M Standes- t Spiel- S für die Grundstücke r t 8 J u r r . r l s tr Theaterhaus 1 o 2 ac t14 r t . s 1 1 . r k A plätze 3 st 8 34 21 - s amt I e 3 a s Sozio-kult. 11 k 3 Sportplatz c 0 . 5 58 Sporthalle c r - 1 Spiel- h S 6 1 1 Zentrum 5 1 ü t r S 5 i te 2 o 4 3 m i T t 4 G 0 n 1 R s r 2 - 7 . -

Stadtumbaugebiet Spandauer Vorstadt Bezirk Mitte

Stadtumbaugebiet Spandauer Vorstadt Kinderbeteiligung in der Kita Kleine Auguststraße © Brigitte Gehrke Ansprechpartner: Ergebnis Senatsverwaltung für Um die großen Herausforderungen der Gebietsentwicklung in der Spandau- Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen er Vorstadt meistern zu können, profitierte das Gebiet von drei Program- Referat IV B Soziale Stadt, Stadtumbau, men der Städtebauförderung: Es war als Sanierungsgebiet, als Gebiet des Zukunftsinitiative Stadtteil Städtebaulichen Denkmalschutzes und als Stadtumbaugebiet ausgewiesen. Birgit Hunkenschroer IV B 46 Durch diesen gezielten Mitteleinsatz wurde nicht nur die bauliche Erneue- Telefon (030) 90139 4866 rung der privaten und öffentlichen Gebäude gemeistert und damit bezahl- Stadtumbau [email protected] barer Wohnraum gesichert. Es konnte gleichzeitig dem hohem Umnut- zungs- und Veränderungsdruck mit sinnvollen Investitionen in die soziale Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin Infrastruktur und qualitätsvollen öffentlichen Raum begegnet werden. FB Stadtplanung Für die Konkretisierung der Pläne und die Auswahl geeigneter Maßnahmen Wolf-Dieter Blankenburg Stadt 1 513 zur Gebietsentwicklung wurde die Bewohnerschaft, örtliche Gewerbetrei- Telefon (030) 9018 45721 bende und Hauseigentümer beteiligt. [email protected] Durch die Förderung ist die Spandauer Vorstadt bis heute für alle Bewoh- nergruppen mit ihren unterschiedlichen Bedürfnissen, insbesondere jedoch für Haushalte mit Kindern, attraktiv geblieben. Stadtumbaugebiet Spandauer Vorstadt Ein deutliches -

(Or) Dead Heroes?

Juli Székely HEROES AFTER THE END OF THE HEROIC COMMEMORATING SILENT HEROES IN BERLIN Living (or) dead heroes? Although meditations over the influence of key figures on the course of history have already been present since antiquity, the heroic imagination of Europe considerably changed in the nineteenth century when the phenomenon of hero worship got deeply interwoven with a project of nation-states.1 As historian Maria Todorova describes, ‘the romantic enterprise first recovered a host of “authentic” folk heroes, and encouraged the exalted group identity located in the nation’ and then it ‘underwrote the romantic political vision of the powerful and passionate individual, the voluntaristic leader, the glorious sculptor of human destinies, the Great Man of history.’2 Nevertheless, in the period after 1945 these great men – who traditionally functioned as historical, social and cultural models for a particular society – slowly began to appear not that great. In 1943 already Sidney Hook cautioned that ‘a democratic community must be eternally on guard’ against heroic leaders because in such a society political leadership ‘cannot arrogate to itself heroic power’.3 But after World War II the question was not simply about adjusting the accents of heroism, as Hook suggested, but about the future legitimacy of the concept itself. Authors extensively elaborated on the crises of the hero that, from the 1970s, also entailed a Juli Székely, ‘Heroes after the end of the heroic. Commemorating silent heroes in Berlin’, in: Studies on National Movements, -

Gestaltungs- Verordnung Historisches Zentrum

Architekturgespräch Gestaltungsverordnung historisches Zentrum Diskussion zum Entwurf 23. April 09 I 19.00 Uhr Bauakademie, Musterraum Schinkelplatz 1 / Werderscher Markt 10117 Berlin Gestaltungs- verordnung historisches Zentrum Diskussion zum Entwurf Wir laden Sie herzlich ein, mit Senatsbau- Entwurf Stand 18.02.2009 direktorin Regula Lüscher über den Entwurf Verordnung der Gestaltungsverordnung für das historische über die äußere Gestaltung baulicher Anlagen Zentrum Berlins zu diskutieren. im historischen Zentrum Berlins im Bezirk Mitte, Ortsteil Mitte Mit Hilfe dieser Regelungen soll das Erschei- (Gestaltungsverordnung historisches Zentrum) nungsbild im repräsentativsten und am stärk- Vom ..................... sten von historisch bedeutsamen Gebäuden geprägten Bereich des historischen Zentrums Auf Grund des § 12 Abs. 1 i.V.m. § 12 Abs. 3 des Gesetzes zur Ausführung des im Umfeld der Straße Unter den Linden, des Baugesetzbuches (AGBauGB) in der Fassung vom 7. November 1999 (GVBl. Gendarmenmarktes sowie der Museumsinsel S. 578), zuletzt geändert durch Art. I Nr. 4 des Gesetzes vom 3. November 2005 bewahrt und baulich weiterentwickelt werden. (GVBl. S. 692), wird verordnet: § 1 Regelungsziel und Geltungsbereich (1) Diese Verordnung soll sicherstellen, dass bei der Errichtung oder Ände- rung baulicher Anlagen im historischen Teil des Berliner Zentrums deren äußere Gestaltung der Bedeutung und Qualität dieses Ortes gerecht werden. Die Fest- legungen des Gesetzes zum Schutz von Denkmalen in Berlin (Denkmalschutz- gesetz Berlin – DSchG Bln) -

Spandauer Vorstadt – Die Entwicklungssteuerung Eines Sanierungsgebiets Im Zentrum Berlins

Dorothee Dubrau Bezirksstadträtin für Stadtentwicklung im Bezirk Mitte von Berlin Spandauer Vorstadt – Die Entwicklungssteuerung eines Sanierungsgebiets im Zentrum Berlins 1 Die Spandauer Vorstadt – Entwicklungssteuerung eines Sanierungsgebiets im Zentrum Berlins 1 Das Gebiet 2 Die Ausgangslage 3 Die Sanierungsziele 4 Die Instrumente zur Umsetzung der Sanierungsziele 5 Was ist bisher erreicht worden? 6 Bilanz in Zahlen 7 Resümee und Ausblick Hackescher Markt 2 1 Das Gebiet • Historisch vor der Stadtmauer, vor dem Spandauer Thore gelegen • Das unregelmäßige Straßensystem und der Stadtgrundriss von 1716 sind noch heute vorhanden 3 1 Das Gebiet Herausragende stadträumliche Lage zwischen Alexanderplatz, Regierungsviertel und Friedrich- straße Berlin, Fusionsbezirk Mitte und Ortsteil Mitte Spandauer Vorstadt im Ortsteil Mitte 4 1 Das Gebiet Die Spandauer Vorstadt im räumlichen Kontext der baulichen Verdichtung im zentralen Bereich nach dem Planwerk Innenstadt Spandauer Vorstadt Planwerk Innenstadt 5 1 Das Gebiet Rahmendaten und Besonderheiten •Fläche 67 ha • Grundstücke 572 • davon unbebaut, 1993 120 • restitutionsbelastete Grundstücke, 1992 96,3 % • Baudenkmale 108 • Einwohner, 2004 8 252 • Flächendenkmal • Sanierungsgebiet seit 1993 • Gebiet zur Erhaltung baulicher Anlagen und der städtebaulichen Eigenart seit 1993 • Fördergebiet des Programms Städtebaulicher Denkmalschutz seit 1991 6 2 Die Ausgangslage • Vernachlässigte, verfallene, vielfach nicht bewohnbare Altbauten • Ca. 25 % der Läden standen leer • Etwa 20 % der Grundstücke unbebaut, -

Karl-Marx-Allee (Stalinallee), Frankfurter Tor Osthafen, Oberbaumbr

A 3: Die City und der Westen, ab Alex/an Zoo (6 h) ● Karl-Marx-Allee (Stalinallee), Frankfurter Tor ● Osthafen, Oberbaumbrücke, East-Side-Gallery, O2-World, Ostbahnhof ● Alexanderplatz, Alexa, Fernsehturm ● Rotes Rathaus, Stadthaus und Nikolaiviertel ● Schlossplatz, (Schloss-) Baustelle Humboldtforum, Humboldtbox, Staatsrat ● Berliner Dom, Museumsinsel ● Bahnhof Friedrichstraße, Tränenpalast, Admiralspalast ● Pariser Platz , Unter den Linden, Russische Botschaft ● Friedrichforum mit Staatsoper, Hedwigs-Kathedrale und Humboldtuniversität ● Neue Wache, Zeughaus, Opern- und Kronprinzenpalais, Kommandantur ● Spandauer Vorstadt, Hackesche Höfe, Oranienburger Straße, Neue Synagoge ● Tacheles, Friedrichstadtpalast ● Hauptbahnhof, Charité, Wirtschaftsministerium ● Band des Bundes mit Kanzleramt und Parlamentsbauten, Reichstag ● Haus der Kulturen der Welt , Schloss Bellevue mit Bundespräsidialamt ● Großer Stern mit Siegessäule, Straße des 17. Juni ● Pause am Brandenburger Tor ● Holocaust-Mahnmal, Führerbunker, Bundesrat, Wilhelmplatz ● Friedrichstraße mit Friedrichstadtpassagen ● Gendarmenmarkt mit Deutschem und Französischem Dom, Schauspielhaus ● Außenministerium, Townhouses an der Neuen Kurstraße ● Checkpoint Charlie ● Highflyer, Finanzministerium, Wilhelmstraße ● Abgeordnetenhaus, Martin-Gropius-Bau, Topografie des Terrors, Mauer ● Potsdamer Platz mit Daimlercity, Sony- und Beisheimcenter ● Kulturforum Tiergarten mit Philharmonie, Neuer Nationalgalerie usw. ● Diplomatenviertel am Tiergarten ● Technische Universität ● Schloss Charlottenburg ● -

Pdf/133 6.Pdf (Abgerufen Am 07.04.02)

ARBEITSBERICHTE Geographisches Institut, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin M. Schulz (Hrsg.) Geographische Exkursionen in Berlin Teil 1 Heft 93 Berlin 2004 Arbeitsberichte Geographisches Institut Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Heft 93 M. Schulz (Hrsg.) Geographische Exkursionen in Berlin Teil 1 Berlin 2004 ISSN 0947 - 0360 Geographisches Institut Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Sitz: Rudower Chaussee 16 Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin (http://www.geographie.hu-berlin.de) Vorwort Der vorliegende Band ist im Rahmen eines Oberseminars zur Stadtentwicklung Berlins im Sommersemester 2002 entstanden. Die Leitidee der Lehrveranstaltung war die Kopplung von zwei wichtigen Arbeitsfeldern für Geographen - die Bearbeitung von stadtgeographischen Themen in ausgewählten Gebieten der Stadt und die Erarbeitung und Durchführung einer Exkursion zu diesem Thema. Jeder Teilnehmer konnte sich eine für ihn interessante Thematik auswählen und musste dann die Orte in Berlin suchen, in denen er das Thema im Rahmen einer zweistündigen Exkursion den anderen Teilnehmern des Oberseminars vorstellte. Das Ergebnis dieser Lehrveranstaltung liegt in Form eines Exkursionsführers vor. Die gewählten Exkursionsthemen spiegeln eine große Vielfalt wider. Sie wurden inhaltlich in drei Themenbereiche gegliedert: - Stadtsanierung im Wandel (drei Exkursionen) - Wandel eines Stadtgebietes als Spiegelbild politischer Umbrüche oder städtebaulicher Leitbilder (sieben Exkursionen) und - Bauliche Strukturen Berlins (drei Exkursionen). Die Exkursionen zeugen von dem großen Interesse aller beteiligten Studierenden an den selbst gewählten Themen. Alle haben mit großem Engagement die selbst erarbeitete Aufgabenstellung bearbeitet und viele neue Erkenntnisse gewonnen. Besonders hervorzuheben ist die Bereitschaft und Geduld von Herrn Patrick Klemm, den Texten der einzelnen Exkursionen ein einheitliches Layout zu geben, so dass die Ergebnisse nun in dieser ansprechenden Form vorliegen. Marlies Schulz Mai 2003 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS STADTSANIERUNG IM WANDEL 1. -

Dienstag, 02. Juni 2020 Beschluss Des Kreisvorstands Der SPD Berlin

Dienstag, 02. Juni 2020 1 Beschluss des Kreisvorstands der SPD Berlin-Mitte Zukunftsort Berliner Mitte: lebenswert – klimaresilient – gemeinwohlorientiert – geschichtsbewusst – autoarm – kulturstark Unser Plan für eine lebendige und lebenswerte Stadtmitte Die Berliner Mitte ist unter Berücksichtigung der sorgfältig im Partizipationsprozess „Alte Mitte. neue Liebe“ erarbeiteten und vom Abgeordnetenhaus im Jahr 2016 beschlossenen „Bürgerleitlinien für die Berliner Mitte“ behutsam zu reurbanisieren. Hierbei sind die Bereiche Molkenmarkt, Nikolaiviertel, Museumsinsel, Humboldtforum, Alt-Cölln, Fischerinsel, Spittelmarkt und Leipziger Straße, Unter den Linden, Spandauer Vorstadt, Alexanderplatz, Karl-Marx-Allee und Nördliche Luisenstadt konzeptionell einzubeziehen. Das Spreeufer ist, als verbindendes Element der Stadtmitte, in das Konzept mit einzubeziehen. Rathaus- und Marx-Engels-Forum: Für den anstehenden Wettbewerb zur Gestaltung von Rathaus- und Marx-Engels-Forum sind – aufbauend auf den zehn Bürgerleitlinien – folgende Aspekte zu berücksichtigen: Verkehr: Der Autoverkehr ist zugunsten von Fußgängern, Radfahrer*innen und dem öffentlichen Nahverkehr radikal auf ein Minimum zu reduzieren. Die Karl-Liebknecht-Straße wird je Richtung auf Tram und eine überbreite Mischspur für Bus, Taxi und notwendigen Anliegerverkehr sowie einen Radweg reduziert. Dies macht die Pflanzung von zwei Reihen Straßenbäumen möglich. Die Spandauer Straße wird eine die beiden Grünflächen verbindende Platzfläche, die die Ausweichstrecke für die neue Tram Richtung Mühlendammbrücke aufnimmt. Die reguläre Strecke der Tram wird über die Rathausstraße Richtung Alexanderplatz geführt. Fußgänger*innen sollen Vorfahrt erhalten. Alle öffentlichen Flächen sollen in vorbildlicher Weise barrierefrei gestaltet werden. Kultur und Geschichte: Die vorhandenen Denkmäler (auch Luther-Denkmal, Mendelssohn- Denkmal, die beiden Arbeiter vis-a-vis zum Rathaus, das Marx-Engels-Denkmal) sollen erhalten bleiben. Der Neptunbrunnen soll an seinem derzeitigen Platze erhalten bleiben. -

PDF-Dokument

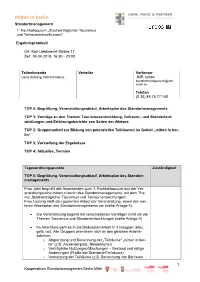

mitten in berlin Standortmanagement 1. Fachkolloquium „Stadtverträglicher Tourismus und Teilraumentwicklungen“ Ergebnisprotokoll Ort: Karl-Liebknecht-Straße 11 Zeit: 04.04.2019, 16:30 - 20:00 Teilnehmende Verteiler Verfasser siehe Anhang Teilnahmeliste JMP, urbos standortmanagement@jahn- mack.de Telefon (0 30) 85 75 77 140 TOP 0: Begrüßung, Veranstaltungsablauf, Arbeitsplan des Standortmanagements TOP 1: Vorträge zu den Themen Tourismusentwicklung, Teilraum-, und Standortent- wicklungen und Erfahrungsberichte von Seiten der Akteure TOP 2: Gruppenarbeit zur Bildung von potenziellen Teilräumen im Gebiet „mitten in ber- lin“ TOP 3: Vorstellung der Ergebnisse TOP 4: Aktuelles, Termine Tagesordnungspunkte Zuständigkeit TOP 0: Begrüßung, Veranstaltungsablauf, Arbeitsplan des Standort- managements Frau Jahn begrüßt alle Anwesenden zum 1. Fachkolloquium aus der Ver- anstaltungsreihe mitten in berlin des Standortmanagements, mit dem The- ma „Stadtverträglicher Tourismus und Teilraumentwicklungen“. Frau Lassnig stellt den geplanten Ablauf der Veranstaltung, sowie den wei- teren Arbeitsplan des Standortmanagements vor (siehe Anlage II) Die Veranstaltung beginnt mit verschiedenen Vorträgen rund um die Themen Tourismus und Standortentwicklungen (siehe Anlage II) Im Anschluss geht es in die Diskussion/Arbeit in 3 Gruppen (blau, gelb, rot). Alle Gruppen orientieren sich an den gleichen Arbeits- schritten o Abgrenzung und Benennung der „Teilräume“ „mitten in ber- lin“ (z.B. Alexanderplatz, Nikolaiviertel) o Verträgliche Nutzungen/Mischungen – Bestand -

MEET BERLIN DAY SIGHTSEEING TOURS 02:00 - 05:00 Pm

MEET BERLIN DAY SIGHTSEEING TOURS 02:00 - 05:00 pm OFF THE BEATEN TRACK This tour will be an emotional, entertaining and informative experience with your guide Burkhard. Here are the »Big 5« of this tour: the »Abandoned Room« - an art installation, the «DC3-Airplane« - used during the airlift of Cold War time, the »I. M Pei Building« - a masterpiece of the world wide acknowledged architect, the »Tiergarten Park« - Berlin’s huge green lung, an unexpected leisure area and - last but not least - I will surprise you with nice locations, where to have a coffee during our tour and where to shop. Your Berlin Insider: Burkhard Heyl BLIND DATE BERLIN-CHARLOTTENBURG Charlottenburg, the city’s former intellectual and cultural center during the 1920s was the main shopping area during the cold war period. We might find boutiques and Pop-up-Stores while strolling on Kurfürstendamm boulevard, visit some renowned art gallery that has suddenly moved here, see the Charlottenburg Palace facade in fresh yellow paint, find a construction site where until yesterday used to be the Memorial church bell tower and discover a design café with view into the zoo. Whatever we find, you might love it. Your Berlin Insider: Dr. Jeannette Malin-Berdel BERLIN – A RAPIDLY CHANGING CITY Berlin has always been a city of change, but since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the changes have become even more rapid. Half of the buildings in the center of Berlin were built after reunification. Over 200 billion euros were invested in new buildings, refurbishments and infrastructure. Famous architects such as Renzo Piano, Lord Norman Foster, Daniel Liebeskind and Peter Eisenman have left their marks here. -

101 Berlin Geheimtipps Und Top-Ziele

IWANOWSKI’S Insider-Tipps von Berlin-Experten 11 Ausflüge in die Umgebung „Anregende Tipps, die neugierig machen und informieren.“ Eine Leserin Tipps für individuelle Entdecker 101 BERLIN GEHEIMTIPPS UND TOP-ZIELE Mit vielen Karten Iwanowski 101 Berlin Karte U1 237 x 180 mm 19.09.2016 Stendaler Lehrter Str. Chausseestr. 24 101 48 16 Heide- str. Naturkunde- F Str. Nord- Veteranen- eh Berlin Innenstadt Invaliden- A. Brunnen- str. rb e museum e e Metzer Birkenstr.Birkenstr. Nordbf. Volkspark l l Kruppstr. friedhof l l Schifffahrtskanal bf. in Ackerstr. am e Birken- Wils-str. Scharnhorststr. r ASenefel- str. Str. Invali- Garten- den- str. Bergstr.str. Str. Z Str. Wein- Hamburger Mus. f. Weinb.-wegeh Lottum- str. r derpl. str. d S r. Rathenower Str. Habersaathstr. berg en tr e S t Wiclefstr. B ic . s a S und Lehrter Naturkunde Rosen- ke Christinenstr. u ar Post- o r a b r S h . rü Fritz- Invaliden- s Schröder- thaler Pl. t n b ck nacker stadion i str. r. Containerbf. Chausseestr. g ö ß e park 60 a r Hess. N - h r Bandelstr. MO ABIT Torstr. c t S Perleberger Str. o S t Waldenser- str. Schloß- Str. v Torstr. S r Tieck- a str.s R . l t Linienstr. Mus. f. i r s . o Linienstr. RRosa-Luxemburg-Pl.osa-Luxemburg-Pl. s Große Hamburger Str. Dreysestr. Hannoversc t 32 s Park Gegenwart h 40 r e . e n . ner Lehrter Str. Invaliden- str. t r Torstr.49 Emde- Linienstr. Luisenstr. S h t r Torstr. Mulackstr. s Bremer Str. -

I/2021 Landesparteitag 24.04.2021 Antrag 50/I/2020

I/2021 Landesparteitag 24.04.2021 Antrag 50/I/2020 KDV Mitte Zukunftsort Berliner Mitte: lebenswert – klimaresilient – gemeinwohlorientiert – geschichtsbewußt – autoarm – kulturstark Beschluss: Die Berliner Mitte ist unter Berücksichtigung der sorgfältig im Partizipationsprozess „Alte Mitte. neue Liebe“ erarbeiteten und vom Abgeordnetenhaus im Jahr 2016 beschlossenen „Bürgerleitlinien für die Berliner Mitte“ behutsam zu reurbanisieren. Hier- bei sind die Bereiche Molkenmarkt, Nikolaiviertel, Museumsinsel, Humboldtforum, Alt-Cölln, Fischerinsel, Spittelmarkt und Leipziger Straße, Unter den Linden, Spandauer Vorstadt, Alexanderplatz, Karl-Marx-Allee und Nördliche Luisenstadt konzep- tionell einzubeziehen. Das Spreeufer ist, als verbindendes Element der Stadtmitte, in das Konzept mit einzubeziehen. Rathaus- und Marx-Engels-Forum: Für den anstehenden Wettbewerb zur Gestaltung von Rathaus- und Marx-Engels-Forum sind – aufbauend auf den zehn Bürgerleitlinien – folgende Aspekte zu berücksichtigen: Verkehr: Der Autoverkehr ist zugunsten von Fußgängern, Radfahrer*innen und dem öffentlichen Nahverkehr radikal auf ein Minimum zu reduzieren. Die Karl-Liebknecht-Straße wird je Richtung auf Tram und eine überbreite Mischspur für Bus, Taxi und notwendigen Anliegerverkehr sowie einen Radweg reduziert. Dies macht die Pflanzung von zwei Reihen Straßenbäumen möglich. Die Spandauer Straße wird eine die beiden Grünflächen verbindende Platzfläche, die die Ausweichstrecke für die neue Tram Richtung Mühlendammbrücke aufnimmt. Die reguläre Strecke der Tram wird über die Rathausstraße Richtung Alexan- derplatz geführt. Fußgänger*innen sollen Vorfahrt erhalten. Alle öffentlichen Flächen sollen in vorbildlicher Weise barrierefrei gestaltet werden. Kultur und Geschichte: Die vorhandenen Denkmäler (auch Luther-Denkmal, Mendelssohn-Denkmal, die beiden Arbeiter vis- a-vis zum Rathaus, das Marx-Engels-Denkmal) sollen erhalten bleiben. Der Neptunbrunnen soll an seinem derzeitigen Platze erhalten bleiben. Auf dem Schlossplatz kann über einen Wettbewerb ein neuer Brunnen geschaffen werden.