The Historical Aspects of Pan-Africanism a Personal Chronicle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dangerous Vagabonds”: Resistance to Slave

“DANGEROUS VAGABONDS”: RESISTANCE TO SLAVE EMANCIPATION AND THE COLONY OF SENEGAL by Robin Aspasia Hardy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2016 ©COPYRIGHT by Robin Aspasia Hardy 2016 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION PAGE For my dear parents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 Historiography and Methodology .............................................................................. 4 Sources ..................................................................................................................... 18 Chapter Overview .................................................................................................... 20 2. SENEGAL ON THE FRINGE OF EMPIRE.......................................................... 23 Senegal, Early French Presence, and Slavery ......................................................... 24 The Role of Slavery in the French Conquest of Senegal’s Interior ......................... 39 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 51 3. RACE, RESISTANCE, AND PUISSANCE ........................................................... 54 Sex, Trade and Race in Senegal ............................................................................... 55 Slave Emancipation and the Perpetuation of a Mixed-Race -

Practical Information – Dakar

Practical information – Dakar Dakar Dakar, capital of Senegal and one of the chief seaports on the western African coast. It is located midway between the mouths of the Gambia and Sénégal rivers on the south-eastern side of the Cape Verde Peninsula, close to Africa’s most westerly point. Dakar’s harbour is one of the best in Western Africa, being protected by the limestone cliffs of the cape and by a system of breakwaters. The city’s name comes from dakhar, a Wolof name for the tamarind tree, as well as the name of a coastal Lebu village that was located south of what is now the first pier. King Fahd Conference Centre The meetings will be held at the King Fahd Conference Centre which also houses the King Fahd Hotel. Those of you staying at the King Fahd Hotel can move from the lobby to the Conference Centre without leaving the building. The Yaas Hotel is the closest recommended hotel to the venue and is only 5 minutes away. Attached is a map of the King Fahd Conference Centre for reference. The Airport The main airport in Dakar is the Blaise Diagne International (DSS). Blaise Diagne International Airport is located on the east of the downtown of Dakar near the town of Diass. It is linked to the city via taxis, busses and shuttles. Travel to and from the Airport The Government of Senegal has kindly offered shuttle busses between the airport and the hotels recommended to the Secretariat. Please send Leah Krogsund ([email protected]) your arrival and departure dates and times should you require the use of these services. -

The Crisis, Vol. 1, No. 2. (December, 1910)

THE CRISIS A RECORD OF THE DARKER RACES Volume One DECEMBER, 1910 Number Two Edited by W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS, with the co-operation of Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, VV. S. Braithwaite and M. D. Maclean. CONTENTS Along the Color Line 5 Opinion . 11 Editorial ... 16 Cartoon .... 18 By JOHN HENRY ADAMS Editorial .... 20 The Real Race Prob lem 22 By Profeaor FRANZ BOAS The Burden ... 26 Talks About Women 28 By Mn. J. E. MILHOLLAND Letters 28 What to Read . 30 PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE National Association for the Advancement of Colored People AT TWENTY VESEY STREET NEW YORK CITY ONE DOLLAR A YEAR TEN CENTS A COPY THE CRISIS ADVERTISER ONE OF THE SUREST WAYS TO SUCCEED IN LIFE IS TO TAKE A COURSE AT The Touissant Conservatory of Art and Music 253 West 134th Street NEW YORK CITY The most up-to-date and thoroughly equipped conservatory in the city. Conducted under the supervision of MME. E. TOUISSANT WELCOME The Foremost Female Artist of the Race Courses in Art Drawing, Pen and Ink Sketching, Crayon, Pastel, Water Color, Oil Painting, Designing, Cartooning, Fashion Designing, Sign Painting, Portrait Painting and Photo Enlarging in Crayon, Water Color, Pastel and Oil. Artistic Painting of Parasols, Fans, Book Marks, Pin Cushions, Lamp Shades, Curtains, Screens, Piano and Mantel Covers, Sofa Pillows, etc. Music Piano, Violin, Mandolin, Voice Culture and all Brass and Reed Instruments. TERMS REASONABLE THE CRISIS ADVERTISER THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION for the ADVANCEMENT of COLORED PEOPLE OBJECT.—The National Association COMMITTEE.—Our work is car for the Advancement of Colored People ried on under the auspices of the follow is an organization composed of men and ing General Committee, in addition to the women of all races and classes who be officers named: lieve that the present widespread increase of prejudice against colored races and •Miss Gertrude Barnum, New York. -

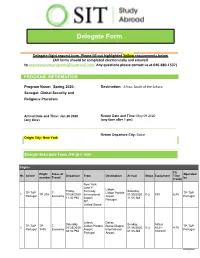

Delegate Form

Delegate Form Delegate flight request form. Please fill out highlighted Yellow requirements below (All forms should be completed electronically and emailed to [email protected]. Any questions please contact us at 646-880-1537) PROGRAM INFORMATION Program Name: Spring 2020: Destination: Africa, South of the Sahara Senegal: Global Security and Religious Pluralism Arrival Date and Time: Jan 26 2020 Return Date and Time: May 09 2020 (any time) (any time after 1 pm) Return Departure City: Dakar Origin City: New York Sample Schedule From JFK @ $ 1800 Flights Flt Flight Class of Operated Nr. Airline Departure From Destination Arrival Stops Equipment Time number Travel by (Total) New York, John F. Lisbon, Friday, Kennedy Saturday, TP-TAP T- Lisbon Portela TP-TAP 1 TP 208 01/24/2020 International 01/25/2020 0 () 339 6:35 Portugal Economy Airport, Portugal 11:30 PM Airport, 11:05 AM Portugal NY, United States Lisbon, Dakar, Saturday, Sunday, Airbus TP-TAP TP T- Lisbon Portela Blaise Diagne TP-TAP 2 01/25/2020 01/26/2020 0 () A321- 4:15 Portugal 1485 Economy Airport, International Portugal 08:50 PM 01:05 AM 100/200 Portugal Airport, 1 Delegate Form Dakar, Paris, Saturday, Sunday, AF-Air Q- Blaise Diagne Charles De Boeing 777- AF-Air 3 AF 719 05/09/2020 05/10/2020 0 () 5:30 France Economy International Gaulle Airport, 300 France 11:05 PM 06:35 AM Airport, France New York, John F. Paris, Sunday, Kennedy Sunday, AF-Air Q- Paris Orly Boeing 777- AF-Air 4 AF 032 05/10/2020 International 05/10/2020 0 () 8:25 France Economy Airport, 200 France 02:15 PM Airport, 04:40 PM France NY, United States Nonrefundable Changeable for a fee 2 bags permitted with AF, Zero bag with TP Please see below for Personal Details. -

The Speculative Fiction of Octavia Butler and Tananarive Due

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University DigitalCommons@WayneState Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 An Africentric Reading Protocol: The pS eculative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due Tonja Lawrence Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Lawrence, Tonja, "An Africentric Reading Protocol: The peS culative Fiction Of Octavia Butler And Tananarive Due" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 198. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. AN AFRICENTRIC READING PROTOCOL: THE SPECULATIVE FICTION OF OCTAVIA BUTLER AND TANANARIVE DUE by TONJA LAWRENCE DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: COMMUNICATION Approved by: __________________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY TONJA LAWRENCE 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my children, Taliesin and Taevon, who have sacrificed so much on my journey of self-discovery. I have learned so much from you; and without that knowledge, I could never have come this far. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the direction of my dissertation director, help from my friends, and support from my children and extended family. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation director, Dr. Mary Garrett, for exceptional support, care, patience, and an unwavering belief in my ability to complete this rigorous task. -

2011 Minerals Yearbook

2011 Minerals Yearbook THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL U.S. Department of the Interior September 2013 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF THE GAMBIA, GUINEA-BISSAU, AND SENEGAL By Omayra Bermúdez-Lugo THE GAMBIA Industrial Minerals Mining in The Gambia was limited to the production of Phosphate Rock.—On February 22, Plains Creek Phosphate industrial minerals and did not play a significant role in the Corp. of Canada announced the results of a technical study country’s economy. In 2011, the Government did not publish [National Instrument 43–101 (NI 43–101)] regarding the mineral production data, and information on the production of economic potential of the Farim phosphate project. Measured clay, ilmenite, laterite, silica sand, and zircon was not available and indicated resources of phosphate rock ore were reported to make reliable estimates of output. Although the Government to be 84 million metric tons (Mt) at an average grade of 29.9% reported production of ilmenite and rutile in 2009 and 2010 P2O5 and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 meters (m). Inferred resources and that of rutile concentrate and zircon in 2007, there were no were estimated to be 44 Mt at an average grade of 29.6% P2O5 known ongoing titanium mineral projects in the country. The and a cutoff thickness of 1.5 m. Plains Creek owned a 50.1% country did not produce petroleum and depended upon imports interest in the Farim deposit and had the right to acquire the to meet its domestic energy requirements. remaining 49.9% interest in the project from GB Minerals AG of Switzerland. -

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal –

The French Model of Assimilation and Direct Rule - Faidherbe and Senegal – Key terms: Assimilation Association Direct rule Mission Dakar–Djibouti Direct Rule Direct rule is a system whereby the colonies were governed by European officials at the top position, then Natives were at the bottom. The Germans and French preferred this system of administration in their colonies. Reasons: This system enabled them to be harsh and use force to the African without any compromise, they used the direct rule in order to force African to produce raw materials and provide cheap labor The colonial powers did not like the use of chiefs because they saw them as backward and African people could not even know how to lead themselves in order to meet the colonial interests It was used to provide employment to the French and Germans, hence lowering unemployment rates in the home country Impacts of direct rule It undermined pre-existing African traditional rulers replacing them with others It managed to suppress African resistances since these colonies had enough white military forces to safeguard their interests This was done through the use of harsh and brutal means to make Africans meet the colonial demands. Assimilation (one ideological basis of French colonial policy in the 19th and 20th centuries) In contrast with British imperial policy, the French taught their subjects that, by adopting French language and culture, they could eventually become French and eventually turned them into black Frenchmen. The famous 'Four Communes' in Senegal were seen as proof of this. Here Africans were granted all the rights of French citizens. -

PAID February 1994 UC San Diego's African-American Newspaper

U.S. POSTAGE PAID LA JOLLA,CA. February 1994 UC San Diego’s African-American Newspaper ! t. The People’sVoice Mission :. The. Voic_....__ee (based on "The People’s Voice Manifesto,’ ~ag...~, TPVVol. 15, ...... No.1, Feb.92) i,, Editorials... The People’sVoice ) Ourmission: Vol.16 No.1 New visions institutionallyracist, but there’s nothing anyone can thosethat do aregetting paid very well. Well maybe do aboutit becausechange is unthinkabletoday. We notthat much, but enough to keepthem complacent. By Paul Beaudry 1) We willeducate and uplift the African-American peoples in gen- needsegregation, blatant racism, and some2000 WAKE UPI!!I!!! lynchingsper yearagain before anybody will do eral.We planto reportpast and current news, and offer commentary on Editors PaulBeau&y, editor-in-chief YEAH,TPV IS IN THEHOUSE! ! ! ! Helloto allyou anything.In themeantime let’s ask the government Thisis a partof thereality that we facetoday and it’s thestate of African-American affairs. oldfans, and welcome for all you new fans. TPV is for anothersocial program so we can he more timeto start being pro-active about your attitudes (as We supportand uplift African-Americans in general, and particu- DeniseCarter backon theblock and we havea newstaff, new ideas, dependenton frees*#t. No, the plantation days are opposedto beingre-active after you’ve been jacked). larlythose on UCSD’scampus. In an eraof decliningenrollment of JamesPatterson andsome new directions we would like to pursue.It’s overand thosedumb niggers over there that are Howare our G.P.A.’s? How is ourenrollment in the African-Americansat UCSD and abroad, we arefully committed to in- greatto seebow many people wanted to seeTPV back studyingtheir heritage are running their mouths Universityof California? When was the last time we BusinessManager in fulleffect and supported us as we worked24-7 (or againabout doing something African. -

"Double Consciousness" in the Souls of Black Folk Ernest Allen Jr

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 9 Special Double Issue: African American Article 5 Double Consciousness 1992 Ever Feeling One's Twoness: "Double Ideals" and "Double Consciousness" in the Souls of Black Folk Ernest Allen Jr. University of Massachusetts Amherst, W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Allen, Ernest Jr. (1992) "Ever Feeling One's Twoness: "Double Ideals" and "Double Consciousness" in the Souls of Black Folk," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Allen: Ever Feeling One's Twoness: "Double Ideals" and "Double Conscious ErnestAllen, Jr. EVER FEELING ONE'S TWONESS: "DOUBLE IDEALS" AND "DOUBLE CONSCIOUSNESS" IN THE SOULS OF BLACK FOLK Two souls, alas! reside within my breast, and each is eager for a separation: in throes of coarse desire, one grips the earth with all its senses; the other struggles from the dust to rise to high ancestral spheres. Ifthere are spirits in the air who hold domain between this world and heaven out ofyour golden haze descend, transport me to a new and brighter life! ---Goethe, Faust N ms The Souls ojBlackFolk publishedat the tum ofthe century, W. -

The Negro in France

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Black Studies Race, Ethnicity, and Post-Colonial Studies 1961 The Negro in France Shelby T. McCloy University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation McCloy, Shelby T., "The Negro in France" (1961). Black Studies. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_black_studies/2 THE NEGRO IN FRANCE This page intentionally left blank SHELBY T. McCLOY THE NEGRO IN FRANCE UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY PRESS Copyright© 1961 by the University of Kentucky Press Printed in the United States of America by the Division of Printing, University of Kentucky Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 61-6554 FOREWORD THE PURPOSE of this study is to present a history of the Negro who has come to France, the reasons for his coming, the record of his stay, and the reactions of the French to his presence. It is not a study of the Negro in the French colonies or of colonial conditions, for that is a different story. Occasion ally, however, reference to colonial happenings is brought in as necessary to set forth the background. The author has tried assiduously to restrict his attention to those of whose Negroid blood he could be certain, but whenever the distinction has been significant, he has considered as mulattoes all those having any mixture of Negro and white blood. -

Du Bois, the NAACP, and the Pan-African Congress of 1919 Author(S): Clarence G

Du Bois, the NAACP, and the Pan-African Congress of 1919 Author(s): Clarence G. Contee Source: The Journal of Negro History , Jan., 1972, Vol. 57, No. 1 (Jan., 1972), pp. 13-28 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2717070 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Association for the Study of African American Life and History and The University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Negro History This content downloaded from 130.58.64.51 on Thu, 11 Feb 2021 17:10:40 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms DU BOIS, THE NAACP, AND THE PAN-AFRICAN CONGRESS OF 1919 by Clarence G. Contee Clarence G. Contee is Associate Professor of History at Howard University. One of the great contributions of W. E. Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963) to the growth of organized Pan-Africanism was the "revival" of the move- ment, which seemed moribund, as his Pan-African Congress convened in Paris in February, 1919. -

Airports and Air Navigation Services Providers

Case Study: Senegal Background There are 20 aerodromes in Senegal. Among them, one receives scheduled international traffic, and four are major regional airports. The international airport is Dakar-Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport, which is also Senegal’s busiest airport. The four most important regional airports are Saint-Louis Airport in the Northeast, Cap Skirring Airport in the Southeast, Ziguinchor airport in the Casamance region, and Tambacounda Airport in the East. Since the suspension of Air Sénégal International in 2009, traffic at these regional airports has decreased substantially. The Directorate of Civil Aviation (DAC, Direction de l’Aviation Civile) used to be a structure of the Ministry of Transport. Its main role was to implement Senegal’s air transport policy and to supervise the provision of airport and air navigation services. These services were delivered by the Agency for Air Navigation Safety in Africa & Madagascar (ASECNA, Agence pour la sécurité de la navigation aérienne en Afrique et à Madagascar). ASECNA was created in 1959 as a multinational public corporation. It comprises 18 Member States from francophone Africa. ASECNA used to operate the Dakar-Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport and other regional airports in Senegal (under the article 10 of the Convention of Dakar of 25 October 1974). More specifically, airports used to be managed by the Senegal National Aeronautic Activities Agency (AAANS, Administration des activités aéronautiques nationales du Sénégal), whose Chief Executive was appointed by ASECNA’s General Director on the advice of the Senegal’s Minister of Civil Aviation. ASECNA still provides air navigation services through six flight information regions (Antananarivo, Brazzaville, Dakar Oceanic and Terrestrial, Niamey, and N’Djamena).