THE TEXTUALITY of the CONSTITUTION and the ORIGINS of ORIGINAL INTENT a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate Sc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

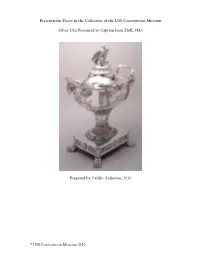

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Congress's Power Over Appropriations: Constitutional And

Congress’s Power Over Appropriations: Constitutional and Statutory Provisions June 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46417 SUMMARY R46417 Congress’s Power Over Appropriations: June 16, 2020 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Sean M. Stiff A body of constitutional and statutory provisions provides Congress with perhaps its most Legislative Attorney important legislative tool: the power to direct and control federal spending. Congress’s “power of the purse” derives from two features of the Constitution: Congress’s enumerated legislative powers, including the power to raise revenue and “pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States,” and the Appropriations Clause. This latter provision states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Strictly speaking, the Appropriations Clause does not provide Congress a substantive legislative power but rather constrains government action. But because Article I vests the legislative power of the United States in Congress, and Congress is therefore the moving force in deciding when and on what terms to make public money available through an appropriation, the Appropriations Clause is perhaps the most important piece in the framework establishing Congress’s supremacy over public funds. The Supreme Court has interpreted and applied the Appropriations Clause in relatively few cases. Still, these cases provide important fence posts marking the extent of Congress’s -

Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rebecca J. Bertrand All Rights Reserved MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand Approved: __________________________________________________________ Brock Jobe, M.A. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Every Massachusetts schoolchild walks Boston’s Freedom Trail and learns the story of the Hancock house. Its demolition served as a rallying cry for early preservationists and students of historic preservation study its importance. Having been both a Massachusetts schoolchild and student of historic preservation, this project has inspired and challenged me for the past nine months. To begin, I must thank those who came before me who studied the objects and legacy of the Hancock house. I am greatly indebted to the research efforts of Henry Ayling Phillips (1852- 1926) and Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1856-1951). Their research notes, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts served as the launching point for this project. This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of my thesis adviser, Brock Jobe. -

Interactive Reader and Study Guide

Interactive Reader and Study Guide HOLT Social Studies United States History Beginnings to 1877 Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Teachers using HOLT SOCIAL STUDIES: UNITED STATES HISTORY may photocopy com- plete pages in sufficient quantities for classroom use only and not for resale. HOLT and the “Owl Design” are registered trademarks licensed to Holt, Rinehart and Winston, registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-03-042643-X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 082 08 07 06 05 Contents Chapter 1 The World before the Opening Chapter 8 The Jefferson Era of the Atlantic Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 66 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 1 Sec 8.1 . 67 Sec 1.1 . 2 Sec 8.2 . 69 Sec 1.2 . 4 Sec 8.3 . 71 Sec 1.3 . 6 Sec 8.4 . 73 Sec 1.4 . 8 Chapter 9 A New National Identity Chapter 2 New Empires in the Americas Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 75 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 10 Sec 9.1 . 76 Sec 2.1 . 11 Sec 9.2 . 78 Sec 2.2 . 13 Sec 9.3 . 80 Sec 2.3 . 15 Chapter 10 The Age of Jackson Sec 2.4 . 17 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 82 Sec 2.5 . -

Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820

128 American Antiquarian Society. [April, BIBLIOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS, 1690-1820 PART III ' MARYLAND TO MASSACHUSETTS (BOSTON) COMPILED BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM The following bibliography attempts, first, to present a historical sketch of every newspaper printed in the United States from 1690 to 1820; secondly, to locate all files found in the various libraries of the country; and thirdly, to give a complete check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society. The historical sketch of each paper gives the title, the date of establishment, the name of the editor or publisher, the fre- quency of issue and the date of discontinuance. It also attempts to give the exact date of issue when a change in title or name of publisher or frequency of publication occurs. In locating the files to be found in various libraries, no at- tempt is made to list every issue. In the case of common news- papers which are to be found in many libraries, only the longer files are noted, with a description of their completeness. Rare newspapers, which are known by only a few scattered issues, are minutely listed. The check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society follows the style of the Library of Con- gress "Check List of Eighteenth Century Newspapers," and records all supplements, missing issues and mutilations. The arrangement is alphabetical by states and towns. Towns are placed according to their present State location. For convenience of alphabetization, the initial "The" in the titles of papers is disregarded. Papers are considered to be of folio size, unless otherwise stated. -

2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

EXPLORING THE HUMAN ENDEAVOR NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES 2ANNU0AL1 REP2ORT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER August 2013 Dear Mr. President, It is my privilege to present the 2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. For forty-seven years, NEH has striven to support excellence in humanities research, education, preservation, access to humanities collections, long-term planning for educational and cultural institutions, and humanities programming for the public. NEH’s 1965 founding legislation states that “democracy demands wisdom and vision in its citizens.” Understanding our nation’s past as well as the histories and cultures of other peoples across the globe is crucial to understanding ourselves and how we fit in the world. On September 17, 2012, U.S. Representative John Lewis spoke on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial about freedom and America’s civil rights struggle, to mark the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He was joined on stage by actors Alfre Woodward and Tyree Young, and Howard University’s Afro Blue jazz vocal ensemble. The program was the culmination of NEH’s “Celebrating Freedom,” a day that brought together five leading Civil War scholars and several hundred college and high school students for a discussion of events leading up to the Proclamation. The program was produced in partnership with Howard University and was live-streamed from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History to more than one hundred “watch parties” of viewers around the nation. Also in 2012, NEH initiated the Muslim Journeys Bookshelf—a collection of twenty-five books, three documentary films, and additional resources to help American citizens better understand the people, places, history, varieties of faith, and cultures of Muslims in the United States and around the world. -

The Federal Constitution and Massachusetts Ratification : A

, 11l""t,... \e ,--.· ', Ir \" ,:> � c.'�. ,., Go'.l[f"r•r•r-,,y 'i!i • h,. I. ,...,,"'P�r"'T'" ""J> \S'o ·� � C ..., ,' l v'I THE FEDERAL CONSTlTUTlON \\j\'\ .. '-1',. ANV /JASSACHUSETTS RATlFlCATlON \\r,-,\\5v -------------------------------------- . > .i . JUN 9 � 1988 V) \'\..J•, ''"'•• . ,-· �. J ,,.._..)i.�v\,\ ·::- (;J)''J -�·. '-,;I\ . � '" - V'-'� -- - V) A TEACHING KIT PREPAREV BY � -r THE COIJMOMVEALTH M,(SEUM ANV THE /JASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES AT COLUM.BIA POINf ]') � ' I � Re6outee Matetial6 6ot Edueatot6 and {I · -f\ 066ieial& 6ot the Bieentennial 06 the v-1 U.S. Con&titution, with an empha6i& on Ma&&aehu&ett6 Rati6ieation, eontaining: -- *Ma66aehu6ett& Timeline *Atehival Voeument6 on Ma&&aehu&ett& Rati6ieation Convention 1. Govetnot Haneoek'6 Me&6age. �����4Y:t4���� 2. Genetal Coutt Re6olve& te C.U-- · .....1. *. Choo6ing Velegate& 6ot I\) Rati6ieation Convention. 0- 0) 3. Town6 &end Velegate Name&. 0) C 4. Li6t 06 Velegate& by County. CJ) 0 CJ> c.u-- l> S. Haneoek Eleeted Pte6ident. --..J s:: 6. Lettet 6tom Elbtidge Getty. � _:r 7. Chatge6 06 Velegate Btibety. --..J C/)::0 . ' & & • o- 8 Hane oe k Pt op o 6e d Amen dme nt CX) - -j � 9. Final Vote on Con&titution --- and Ptopo6ed Amenwnent6. Published by the --..J-=--- * *Clue6 to Loeal Hi&toty Officeof the Massachusetts Secretary of State *Teaehing Matetial6 Michaelj, Connolly, Secretary 9/17/87 < COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS !f1Rl!j OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE CONSTITUTtON Michael J. Connolly, Secretary The Commonwealth Museum and the Massachusetts Columbia Point RATIFICATION OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION MASSACHUSETTS TIME LINE 1778 Constitution establishing the "State of �assachusetts Bay" is overwhelmingly rejected by the voters, in part because it lacks a bill of rights. -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs July 21, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22478 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers in recent years have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. The 10 most recently named aircraft carriers have been named for U.S. presidents (8 ships) and Members of Congress (2 ships). Virginia (SSN-774) class attack submarines are being named for states. An exception occurred on January 8, 2009, when the Secretary of the Navy announced that SSN-785, the 12th ship in the class, would be named for former Senator John Warner. Destroyers are named for U.S. naval leaders and heroes. Littoral Combat Ships (LCSs) are being named for small and medium-sized cities. San Antonio (LPD-17) class amphibious ships are being named for U.S. cities. An exception occurred on April 23, 2010, when the Secretary of the Navy announced that LPD-26, the 10th ship in the class, would be named for the late Representative John P. -

Autumn 2007 Full Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 60 Article 1 Number 4 Autumn 2007 Autumn 2007 Full Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2007) "Autumn 2007 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 60 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol60/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Autumn 2007 60, Number 4 Volume Naval War College: Autumn 2007 Full Issue NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2007 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW Autumn 2007 R COL WA LEG L E A A I V R A N O T C I V I R A M S U S E B I T A T R T I H S E V D U E N T I Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 60 [2007], No. 4, Art. 1 Cover The Kongo-class guided-missile destroyer JDS Chokai (DDF 176) of the Japan Mar- itime Self-Defense Force alongside USS Kitty Hawk (CV 63) on 10 December 2002. The scene is evocative of one of the many levels at which the “thousand-ship navy,” examined in detail in this issue by Ronald E. -

The Commander-In-Chief and the Necessities of War: a Conceptual Framework

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2011 The ommC ander-in-Chief and the Necessities of War: A Conceptual Framework John C. Dehn Loyola University Chicago, School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John C. Dehn, The ommC ander-in-Chief and the Necessities of War: A Conceptual Framework, 83 Temp. L. Rev. 599 (2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEMPLE LAW REVIEW © 2011 TEMPLE UNIVERSITY OF THE COMMONWEALTH SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION VOL. 83 NO. 3 SPRING 2011 ARTICLES THE COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF AND THE NECESSITIES OF WAR: A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK * John C. Dehn While the current Administration has largely abandoned claims of plenary presidential authority to fight the nation’s wars, courts, scholars, and policy makers continue to debate the nature and scope of the powers conferred by the September 18, 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force. This Article examines primarily Supreme Court precedent to distill the general scope and limits of the President’s powers to fight the nation’s international and non-international armed conflicts. It concludes that the Supreme Court has expressly endorsed and consistently observed (although inconsistently applied) two concepts of necessity attributable to the Commander-in- Chief power. The first is military necessity: the power to employ all military measures not prohibited by applicable law and reasonably calculated to defeat a national enemy.