Outfitting USS Constitution During the War of 1812 Matthew Brenckle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

December 2017.Pdf

MILITARY SEA SERVICES MUSEUM, INC. SEA SERVICES SCUTTLEBUTT December 2017 A message from the President Greetings, The year 2017 was another good year for the Museum. Thanks to our Member's dues, a substantial contribution from our most generous member and contributions from a couple of local patriotic organizations, we will end the year financially sound and feeling confident that we will be able to make any emergency repairs and continue to make improvements to the Museum. As reported in previous Scuttlebutts, most of our major projects have been completed. Our upgraded security system with motion activated cameras inside the Museum and outside the shed John Cecil should be completed this month. The construction of a concrete structure for the mid-1600s British Admiralty Cannon should be completed early next year. I hope everyone has a Merry Christmas and a New Year that is happy, healthy and prosperous. On this Christmas day let's all say a prayer for our troops that can't be home with families and loved ones. They are doing a great job of preventing the spread of terrorism and protecting our freedoms. Please say a prayer for their safe return home. John Military Sea Services entry in Sebring's 2017 Veteran's Day Parade The construction on Fred Carino's boat was done by Fred and his brother Chris. The replica of the bow ornament was done by Mary Anne Lamorte and her granddaughter Dominique Juliano. Military Sea Services Museum Hours of Operation 1402 Roseland Avenue, Sebring, Open: Thursday through Saturday Florida, 33870 Phone: (863) 385-0992 Noon to 4:00 p.m. -

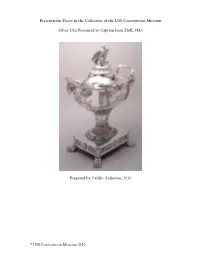

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Volunteer Manual

Gundalow Company Volunteer Manual Updated Jan 2018 Protecting the Piscataqua Region’s Maritime Heritage and Environment through Education and Action Table of Contents Welcome Organizational Overview General Orientation The Role of Volunteers Volunteer Expectations Operations on the Gundalow Workplace Safety Youth Programs Appendix Welcome aboard! On a rainy day in June, 1982, the replica gundalow CAPTAIN EDWARD H. ADAMS was launched into the Piscataqua River while several hundred people lined the banks to watch this historic event. It took an impressive community effort to build the 70' replica on the grounds of Strawbery Banke Museum, with a group of dedicated shipwrights and volunteers led by local legendary boat builder Bud McIntosh. This event celebrated the hundreds of cargo-carrying gundalows built in the Piscataqua Region starting in 1650. At the same time, it celebrated the 20th-century creation of a unique teaching platform that travelled to Piscataqua region riverfront towns carrying a message that raised awareness of this region's maritime heritage and the environmental threats to our rivers. For just over 25 years, the ADAMS was used as a dock-side attraction so people could learn about the role of gundalows in this region’s economic development as well as hundreds of years of human impact on the estuary. When the Gundalow Company inherited the ADAMS from Strawbery Banke Museum in 2002, the opportunity to build a new gundalow that could sail with students and the public became a priority, and for the next decade, we continued the programs ion the ADAMS while pursuing the vision to build a gundalow that could be more than a dock-side attraction. -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

USS Constitution Vs. HMS Guerriere

ANTICIPATION 97 Anticipation What do sailors feel as they wait for battle to begin? Fear – Sailors worry that they or their friends might not survive the battle. What frightens you? Excitement – The adrenaline pumps as the moment the sailors have been training for arrives. How do you feel when something you’ve waited for is about to happen? Anxiety – Sailors are nervous because no one knows the outcome of the battle. What makes you anxious? Illustration from the sketchbook of Lewis Ashfield Kimberly, 1857-1860 Kimberly was Lieutenant on board USS Germantown in the 1850s Collection of the USS Constitution Museum, Boston 98 Gun Crew’s Bible As sailors waited for battle to begin, they were alone with their thoughts. They had time to dwell on the fear that they might never see their families again. Some gun crews strapped a Bible like this one to their cannon’s carriage for extra protection. Bible issued by the Bible Society of Nassau Hall, Princeton, New Jersey Bible was strapped to the carriage of a gun nicknamed “Montgomery” on board USS President, 1813 Collection of the USS Constitution Museum, Boston 99 ENGAGEMENT 100 What are the characteristics of a brave sailor? Courage – Sailors push fear aside to do their job. What have you done that took courage? Responsibility – Each sailor has to do his duty to his country, ship, and shipmates. What are your responsibilities to your community, school, or family? Team Player – Working together is critical to succeed in battle. How do you work or play as part of a team? 101 Engagement USS Constitution vs. -

Museum of Science the Roger Williams Park Zoo New England

The Museum of Fine Arts Price: $10.00 per With 450,000 objects, you will find person / Additional breathtaking works of art, from masters $8.00 for special of American painting to the icons of exhibitions Impressionism, from exquisite Asian People: Max of 2 scrolls to Egyptian mummies, at every turn. Museum of Science Price: $10.00 To reserve a pass: Experience the Museum of Science where People: Max of 4 Call the library - (781) 293-2271, or science comes alive with over 600 Does not include the interactive exhibits that let you explore the Reserve online - holmespubliclibrary.org Omni, Planetarium, world around you. or combination (follow Museum Passes link) tickets. A valid library card is required to check out a pass. New England Aquarium Price: $10.00 /person Boston Children's Museum Price: half-price Boston Children's Museum Price: half-price People: Max of 4 admission The aquarium is one of the premier visitor admission Boston Children’s Museum is the place for attractionsBoston Children’s in Boston Museum and is a isglobal the place for People: Max of 4 Does People:not include Max of 4 children and the adults in their lives to leaderchildren in ocean and the exploration adults in andtheir marine lives to experience the fun of learning. experience the fun of learning. Aquarium boat conservation. Highlights include a 4-story programs or IMAX glass ocean tank with a coral reef display. shows. Boston Harbor Islands Price: 2-for-1 Boston Harbor Islands Price: 2-for-1 A National Park, comprised of 34 island, 8 of ferry fee A National Park, comprised of 34 island, 8 of ferry fee which are accessible via seasonal ferry. -

Digital 3D Reconstruction of British 74-Gun Ship-Of-The-Line

DIGITAL 3D RECONSTRUCTION OF BRITISH 74-GUN SHIP-OF-THE-LINE, HMS COLOSSUS, FROM ITS ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION PLANS A Thesis by MICHAEL KENNETH LEWIS Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Filipe Castro Committee Members, Chris Dostal Ergun Akleman Head of Department, Darryl De Ruiter May 2021 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2021 Michael Lewis ABSTRACT Virtual reality has created a vast number of solutions for exhibitions and the transfer of knowledge. Space limitations on museum displays and the extensive costs associated with raising and conserving waterlogged archaeological material discourage the development of large projects around the story of a particular shipwreck. There is, however, a way that technology can help overcome the above-mentioned problems and allow museums to provide visitors with information about local, national, and international shipwrecks and their construction. 3D drafting can be used to create 3D models and, in combination with 3D printing, develop exciting learning environments using a shipwreck and its story. This thesis is an attempt at using an 18th century shipwreck and hint at its story and development as a ship type in a particular historical moment, from the conception and construction to its loss, excavation, recording and reconstruction. ii DEDICATION I dedicate my thesis to my family and friends. A special feeling of gratitude to my parents, Ted and Diane Lewis, and to my Aunt, Joan, for all the support that allowed me to follow this childhood dream. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee chair, Dr. -

The Consensus View on Camping and Tramping Fiction Is That It First

Camping and Tramping, Swallows and Amazons: Interwar Children’s Fiction and the Search for England Hazel Sheeky A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Newcastle University May 2012 Abstract For many in Britain, the interwar period was a time of significant social, political and cultural anxiety. In the aftermath of the First World War, with British imperial power apparently waning, and with the politics of class becoming increasingly pressing, many came to perceive that traditional notions of British, and particularly English, identity were under challenge. The interwar years saw many cultural responses to the concerns these perceived challenges raised, as seen in H. V. Morton’s In Search of England (1927) and J. B. Priestley’s English Journey (1934). The sense of socio-cultural crisis was also registered in children’s literature. This thesis will examine one significant and under-researched aspect of the responses to the cultural anxieties of the inter-war years: the ‘camping and tramping’ novel. The term ‘camping and tramping’ refers to a sub-genre of children’s adventure stories that emerged in the 1930s. These novels focused on the holiday leisure activities – generally sailing, camping and hiking - of largely middle-class children in the British (and most often English) countryside. Little known beyond Arthur Ransome’s ‘Swallows and Amazons’ novels (1930-1947), this thesis undertakes a full survey of camping and tramping fiction, developing for the first time a taxonomy of this sub-genre (chapter one).