The Ghost Ship on the Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mean Serious Business Page 18

A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION MAY/JUNE 2011 VOL. 18 NO. 3 $9.00 www.TheMeetingMagazines.com THE EXECUTIVE SOURCE FOR PLANNING MEETINGS & INCENTIVES Golf Resorts Mean Serious Business Page 18 Ken A. Crerar, President of The Council of Insurance Agents & Brokers, holds his annual leadership forums at The Broadmoor (pictured) — the venerable Colorado Springs resort featuring three championship golf courses. Photo courtesy of The Broadmoor Small Meetings Page 10 Cruise Meetings Page 24 Arizona Page 28 ISSN 1095-9726 .........................................USPS 012-991 Tapatio Cliffs A COASTAL COMMUNICATIONS CORPORATION PUBLICATION THE EXECUTIVE SOURCE FOR PLANNING MEETINGS & INCENTIVES MAY/JUNE 2011 Vol. 18 No. 3 Photo courtesy of Regent Seven Seas Cruises Seven Photo courtesy of Regent Page 24 FEATURES Seven Seas Navigator features 490 suites with ocean views — the majority with private balconies. The luxury ship 10 Small Meetings sails to the Tropics, Alaska, Are a Big Priority Canada and New England. By Derek Reveron Squaw Peak 18 Golf Resorts Page 10 Mean Business Dunes Photo courtesy of Marina Inn at Grande DEPARTMENTS By Steve Winston The Sand Dollar Boardroom at Marina Inn at Grande Dunes, Myrtle 4 PUBLISHER’S MESSAGE Beach, SC, is 600 sf and offers a distinctive, comfortable environment 6 INDUSTRY NEWS 24 Smooth Sailing for executive and small meetings. All-Inclusive Cruise 6 VALUE LINE Meetings Keep Budgets On an Even Keel 7 EVENTS By John Buchanan 8 MANAGING PEOPLE How to Overcome the Evils of Micromanaging By Laura Stack DESTINATION 34 CORPORATE LADDER 35 READER SERVICES 28 Arizona A Meetings Oasis Elevate your meetings By Stella Johnson At Sanctuary on Camelback Mountain, exciting new venues for Scottsdale luxury Page 28 dining include Praying Monk (left) and XII. -

Ma2014-8 Marine Accident Investigation Report

MA2014-8 MARINE ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT August 29, 2014 The objective of the investigation conducted by the Japan Transport Safety Board in accordance with the Act for Establishment of the Japan Transport Safety Board is to determine the causes of an accident and damage incidental to such an accident, thereby preventing future accidents and reducing damage. It is not the purpose of the investigation to apportion blame or liability. Norihiro Goto Chairman, Japan Transport Safety Board Note: This report is a translation of the Japanese original investigation report. The text in Japanese shall prevail in the interpretation of the report. MARINE ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT Vessel type and name: Container ship BAI CHAY BRIDGE IMO number: 9463346 Gross tonnage: 44,234 tons Vessel type and name: Fishing vessel SEIHOU MARU No. 18 Fishing vessel registration number: KO2-6268 Gross tonnage: 18 tons Accident type: Collision Date and time: At around 23:12 (JST) on January 23, 2013 Location: On a true bearing of approximately 116º and at a distance of 11.4 nautical miles from the Katsuura Lighthouse, Katsuura City, Chiba Prefecture (Approximately 35°03.3'N 140°31.6'E) August 7, 2014 Adopted by the Japan Transport Safety Board Chairman Norihiro Goto Member Tetuo Yokoyama Member Kuniaki Syouji Member Toshiyuki Ishikawa Member Mina Nemoto SYNOPSIS < Summary of the Accident > On January 23, 2013, the container ship BAI CHAY BRIDGE with the master, third officer and 21 other crewmembers on board was proceeding southwestward to Keihin Port, and the fishing vessel SEIHOU MARU No. 18 with the skipper and five other crewmembers on board was proceeding north-northeastward to Choshi Port. -

USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 USS CONSTELLATION Page 4 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Summary The USS Constellation’s career in naval service spanned one hundred years: from commissioning on July 28, 1855 at Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia to final decommissioning on February 4, 1955 at Boston, Massachusetts. (She was moved to Baltimore, Maryland in the summer of 1955.) During that century this sailing sloop-of-war, sometimes termed a “corvette,” was nationally significant for its ante-bellum service, particularly for its role in the effort to end the foreign slave trade. It is also nationally significant as a major resource in the mid-19th century United States Navy representing a technological turning point in the history of U.S. naval architecture. In addition, the USS Constellation is significant for its Civil War activities, its late 19th century missions, and for its unique contribution to international relations both at the close of the 19th century and during World War II. At one time it was believed that Constellation was a 1797 ship contemporary to the frigate Constitution moored in Boston. This led to a long-standing controversy over the actual identity of the Constellation. Maritime scholars long ago reached consensus that the vessel currently moored in Baltimore is the 1850s U.S. navy sloop-of-war, not the earlier 1797 frigate. Describe Present and Historic Physical Appearance. The USS Constellation, now preserved at Baltimore, Maryland, was built at the navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia. -

Cruise Vessels & Ferries

FROM OUR DESIGN PORTFOLIO CRUISE VESSELS & FERRIES Expedition Cruise Vessels (Endeavor Class) 2017 -19 Client / Shipyard: MV WERFTEN, Stralsund, Germany Owner / Operator: Genting International Plc., Malaysia / Crystal Yacht Expedition Cruises, USA ICE Scope of work: Basic Design Assistance & Detail Crystal Endeavor. Class: DNV GL Design. All-Electric Ferry Concept Design 2018 -19 Type: Battery Electric Ferry Duty: Passenger and Car Ferry Capacity: 200 passengers and 45 cars. Speed: 15 knots in open water and operating with 10 knots in harbour. AIDAprima cruise ship. Client / Shipyard: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI). ICE Scope of work: Coordination drawings. Class: DNV GL International Contract Engineering Ltd. © 2019 International Contract Engineering Ro-Ro Passenger Ferry 2003 -04 Client / Shipyard: Chantiers de l' Atlantique, France Owner: Euro-Transmanche 3 BE (2012-Present); Seafrance (2005-2012) Operator: DFDS Seaways France ICE Scope of Work: Detail design: Côte Des Flandres (ex SeaFrance Berlioz (2005-2012)). Yard number O32. Class: BV - hull structure for the entire vessel - machinery & tanks area. Fast Displacement Ro-Ro Passenger Ferry 1999 -02 Client / Shipyard: Hellenic Shipyard, Greece Owner / Operator: Hellenic Seaways ICE Scope of work: 3-D Model (Tribon); Detail design (hulls 1701 and 1702): Coordination drawings, workshop drawings and production information for all disciplines; Full ship FE model. Armand Imbeau II. Class: Lloyd’s Register LNG-powered Ro-Pax Ferry 2013 Client / Shipyard: Chantier Davie Canada Inc. Operator: Société des Traversiers du Québec (STQ) ICE Scope of work: Concept design review; Design planning and scheduling; Design risk analysis; Nissos Mykonos. Class: BV Initial 3-D modeling (Tribon). Oasis of the Seas, the first of the Oasis Class (formerly the Genesis Class). -

The Journey Continues

The Magazine of Volume 67 Moran Towing Corporation November 2020 The J our ney Continu es In Moran’s New Training Programs, Boots, Books, and Technology Redouble a Shared Vision of Safety PHOTO CREDITS Page 25 (inset) : Moran archives Cover: John Snyder, Pages 26 –27, both photos: marinemedia.biz Will Van Dorp Inside Front Cover: Pages 28 –29: Marcin Kocoj Moran archives Page 30: John Snyder, Page 2: Moran archives ( Fort marinemedia.biz Bragg ONE Stork ); Jeff Thoresen ( ); Page 31 (top): Dave Byrnes Barry Champagne, courtesy of Chamber of Shipping of America Page 31 (bottom): John Snyder, (CSA Environmental Achievement marinemedia.biz Awards) Pages 32 –33: John Snyder, Page 3 : Moran archives marinemedia.biz Pages 5 and 7 –13: John Snyder, Pages 3 6–37, all photos: Moran marinemedia.biz archives Page 15 –17: Moran archives Page 39, all photos: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz Page 19: MER archives Page 40: John Snyder, Page 20 –22: John Snyder, marinemedia.biz marinemedia.biz; Norfolk skyline photo by shutterstock.com Page 41: Moran archives Page 23, all photos: Pages 42 and 43: Moran archives Will Van Dorp Inside Back Cover: Moran Pages 24 –25: Stephen Morton, archives www.stephenmorton.com The Magazine of Volume 67 Moran Towing Corporation November 2020 2 News Briefs Books 34 Queen Mary 2: The Greatest Ocean Liner of Our Time , by John Maxtone- Cover Story Graham 4 The Journey Continues Published by Moran’s New Training Programs Moran Towing Corporation Redouble a Shared Vision of Safety The History Pages 36 Photographic gems from the EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Grandone family collection Mark Schnapper Operations REPORTER John Snyder 14 Moran’s Wellness Program Offers Health Coaching Milestones DESIGN DIRECTOR Mark Schnapper 18 Amid Continued Growth, MER Is 38 The christenings of four new high- Now a Wholly Owned Moran horsepower escort tugs Subsidiary People Moran Towing Corporation Ship Call Miles tones 40 50 Locust Avenue Capt. -

M.E.B.A. Telex Times for January 5, 2017

Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (AFL-CIO) 444 N. Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 800 Washington, DC 20001-1570 Hot Off the Press TEL: (202) 257-2825 FAX: (202) 638-5369 To: All Ports Total Pages Including Cover: From: Marco Cannistraro 4 Date: 1/5/17 Telex Times #01 E-Mail: [email protected] MARINE ENGINEERS’ BENEFICIAL ASSOCIATION (AFL-CIO) “On Watch in Peace and War since 1875” M.E.B.A. TELEX TIMES JANUARY 5, 2017 The Official Union Newsletter NUMBER 1 In this issue//Re-Opener with NCL//New Alternate Training Location Procedures//Note on CMES BST Refresher Course//OCEAN GIANT Sails for Operation Deep Freeze//WSF Passenger Fined for Laser Strike & New Incident//Union Plus Scholarships//Oakland, N.O. Rep. Positions// ECONOMIC REOPENER FINALIZED WITH NCL The Union has reached terms with Norwegian Cruise Line-America, Inc. on a reopener covering wage, benefits and work rules for the 32 officer positions aboard the PRIDE OF AMERICA. The cruise ship is the lone U.S.-flag large passenger vessel and also the only cruise ship operating exclusively between the Hawaiian Islands. Our contract with NCL goes through June 2020. Negotiators agreed upon increases in wages and wage related items for each year, as well as boosts to the medical and other plans in each remaining year. NCL is also covering the Pension contribution and improvements were made in other areas such as vacation days, duty pay and travel language among other items. The M.E.B.A. negotiating team was led by Executive V.P. Adam Vokac and included Christian Yuhas, HQ Contracts Rep. -

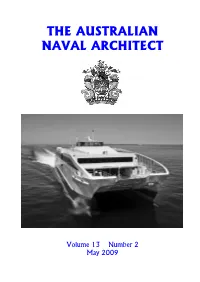

The Australian Naval Architect

THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Volume 13 Number 2 May 2009 The Australian Naval Architect 4 THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL ARCHITECT Journal of The Royal Institution of Naval Architects (Australian Division) Volume 13 Number 2 May 2009 Cover Photo: CONTENTS The 69 m vehicle-passenger catamaran ferry 2 From the Division President Farasan, recently delivered by Austal to Saudi Arabia (Photo courtesy Austal Ships) 2 Editorial 3 Letter to the Editor 4 News from the Sections The Australian Naval Architect is published four times per year. All correspondence and advertising should be sent 22 Coming Events to: 24 Classification Society News The Editor The Australian Naval Architect 25 General News c/o RINA PO Box No. 976 34 From the Crows Nest EPPING NSW 1710 37 What Future for Fast Ferries on Sydney AUSTRALIA email: [email protected] Harbour, Part 2 — Martin Grimm and The deadline for the next edition of The Australian Naval Ar- Garry Fry chitect (Vol. 13 No. 3, August 2009) is Friday 24 July 2009. 42 Computational Analysis of Submarine Propeller Hydrodynamics and Validation against Articles and reports published in The Australian Naval Architect reflect the views of the individuals who prepared Experimental Measurement — G. J. Seil, them and, unless indicated expressly in the text, do not neces- R. Widjaja, B. Anderson and P. A. Brandner sarily represent the views of the Institution. The Institution, 51 Education News its officers and members make no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness or 56 Industry News correctness of information in articles or reports and accept no responsibility for any loss, damage or other liability 58 Vale Ernie Tuck arising from any use of this publication or the information which it contains. -

Master Mates and Pilots July 1953

~]1 ~ .~ In This Issue Gains in Inland Agreements Radio Officers* Urge Talks East German Relief* Ship Sails Hospital Facilities Curtailed VOL. XVI JULY, 1953 NO.7 r I .~. \ Officers of the S. S. "American Inventor" watch cargo assigned to East Germany lowered to hold of the ship. They are (left to right) Ward W. Warren, junior 3rd officer; Floyd Gergler, 3rd officer; Captain H. J. Johnson, ship's master' J. M. Coady, chief officer; James McDermott, 2nd officer. At right, a slingload of milk products is hoisted ahoa ' First Ship With Relief for East Germany Sails The United States Lines cargo vessel, the worked out by him and the West Germany Arner'ican Inventor, sailed from New York at ernment. 5 :00 p, m., July 17, with the first part of the The recent uprisings in East Germany by Mutual Security Agency's $15,000,000 food relief who oppose Communism indicates that all i shipment,. destined for East Germany. In its well behind the Iron Curtain. President holds were 1,600 tons .of flour, dried milk and lard, hower's well-timed move of offering this shi a foretoken only of 50,000 tons that President of food should indicate to the citizens of the Eisenhower had instructed the Agency to send to ern Zone of Germany that they have the ha Germany to relieve the food shortage in the friendship extended to them from across th Eastern Zone. Captain Johnson, of North Bergen, N. J. The remainder of the tonnage was loaded on shipside interview called the shipment "a the American Flyer' on July 23 and on the Ameri while thing" and added that "we must ba can Clipper' sailing July 25, from New York. -

A Century at Sea Jul

Guernsey's A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI Friday - July 19, 2019 A Century at Sea (Day 1) Newport, RI 1: NS Savannah Set of China (31 pieces) USD 800 - 1,200 A collection of thirty-one (31) pieces of china from the NS Savannah. This set of china includes the following pieces: two (2) 10" round plates, three (3) 9 1/2" round plates, one (1) 10" novelty plate, one (1) 9 1/4" x 7" oval plate, one (1) 7 1/4" round plate, four (4) 6" round plates, one (1) ceramic drinking pitcher, one (1) cappachino cup and saucer (diameter of 4 1/2"), two (2) coffee cups and saucers (diameter 4"), one (1) 3 1/2" round cup, one (1) 3" x 3" round cup, one (1) 2 1/2" x 3" drinking glass, one (1) mini cognac glass, two (2) 2" x 4 1/2" shot glasses, three (3) drinking glasses, one (1) 3" x 5" wine glass, two (2) 4 1/2" x 8 3/4" silver dishes. The ship was remarkable in that it was the first nuclear-powered merchant ship. It was constructed with funding from United States government agencies with the mission to prove that the US was committed to the proposition of using atomic power for peace and part of President Eisenhower's larger "Atoms for Peace" project. The sleek and modern design of the ship led to some maritime historians believing it was the prettiest merchant ship ever built. This china embodies both the mission of using nuclear power for peace while incorporating the design inclinations of the ship. -

Norwegian Cruise Line Corporate Overview

NORWEGIAN CRUISE LINE CORPORATE OVERVIEW Norwegian Cruise Line is the innovator in cruise travel with a 44-year history of breaking the boundaries of traditional cruising, most notably with the introduction of Freestyle Cruising which has revolutionized the industry by allowing guests more freedom and flexibility. Today, Norwegian has 11 purpose-built Freestyle Cruising ships providing guests the opportunity to enjoy a relaxed cruise vacation on some of the newest and most contemporary ships at sea. In 2010, the Company reached an agreement with MEYER WERFT GMBH of Germany to build two new next generation Freestyle Cruising ships for delivery in spring 2013 and spring 2014, respectively. Each of the 143,500 gross ton vessels, the largest passenger/cruise ships to be built in Germany, will have approximately 4,000 passenger berths and a rich cabin mix. In February 2000, Norwegian was acquired by Genting Hong Kong Limited formerly Star Cruises Ltd (SES: STRC), a Hong Kong stock exchange listed company, and part of Malaysia's Genting Group. Following the acquisition of Norwegian, Star Cruises became the third largest cruise line in the world. While under 100 percent ownership by Star, the company embarked on an expansion program that involved new ships, on-board product enhancements and innovative itineraries. In August 2007, private equity group, Apollo Management, LP, agreed to make a $1 billion cash equity investment in Norwegian. Under the terms of the investment which closed on January 7, 2008, Apollo became a 50 percent owner of Norwegian and has named a majority of the company’s board with certain consent rights retained by Genting. -

To Bermuda Please Join Us Aboard the Gts Celebrity Summit

TO BERMUDA PLEASE JOIN US ABOARD THE GTS CELEBRITY SUMMIT MAY 6–13, 2018 The SS United States Conservancy is pleased to announce an wonderful cruising opportunity and a ITINERARY chance to support the preservation of the SS United SUNDAY MAY 6 CAPE LIBERTY (BAYONNE, NJ) States and support the SS United States Conservancy’s growing curatorial collections. MONDAY MAY 7 CRUISING While we wish we could fire up the engines, pull up TUESDAY MAY 8 CRUISING the gangways and set sail together aboard America’s Flagship, the Pollin Group and the Conservancy have WEDNESDAY MAY 9 KING’S WHARF, BERMUDA partnered to offer the next best thing: a 7-night cruise THURSDAY MAY 10 KING’S WHARF, BERMUDA sailing in May, 2018 to Bermuda aboard the Celebrity Summit. The cruise will depart from Cape Liberty FRIDAY MAY 11 CRUISING (Bayonne, New Jersey) on Sunday, May 6 and will SATURDAY MAY 12 CRUISING make port at King’s Wharf, Bermuda on May 9 for a three-night stay. The ship will return to New Jersey on SUNDAY MAY 13 CAPE LIBERTY (BAYONNE, NJ) Sunday, May 13. THE CRUISE WILL INCLUDE • Festive social gatherings featuring the music, dance and TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THIS fashion of the transatlantic liner era. VOYAGE, VISIT THE GROUP REGISTRATION PAGE • Riveting talks on design, innovation and “The Way http://www.jpollin.cruiseonegroups.com/SSUnitedStates Things Work” by award-winning author and illustrator David Macaulay. OR CONTACT: GEISHA CUMBERBATCH • Special presentation by Susan Gibbs, SS United States Pollin Group Sales Director Conservancy executive director and granddaughter of the 301.656.5740, Ext. -

Hotel Directions

PHILADELPHIA MARRIOTT DOWNTOWN DIRECTIONS TO THE HOTEL For GPS: Enter 1200 Filbert Street, Philadelphia PA as the address From the North: Using I-95 South-Trenton, Princeton and From the South: Using I-95 North- Phila. Airport, Baltimore, Washington DC Take I-95 to Exit 22 (I-676 West/Central Philadelphia). Follow I-676 West for one mile to the Broad Street exit. At the end of the ramp make the first left onto Vine Street/Local Traffic. Proceed on Vine Street 3 traffic lights to 12th Street. Make a right on onto 12th Street, proceed 3 blocks to Filbert Street. The hotel will be on the right corner of 12th & Filbert, one block past the PA Convention Center. From the Northeast: Using the PA Turnpike, Northeast Extension, Route 9 Follow the Northeast Extension South until it ends. Take I-476 South to Exit 6: (I-76East/Philadelphia). Proceed on I-76 East to Exit 38: (I-676 East/Central Philadelphia). Proceed on I-676 East for one mile to the Broad Street exit. Exit to the left, follow the traffic signs to Vine Street/Local Traffic. Proceed on Vine Street 3 traffic lights to 12th Street. Make a right on 12th Street and proceed 3 blocks to Filbert Street. The hotel will be on the right corner of 12th & Filbert, one block past the PA Convention Center. From the East: Using the New Jersey Turnpike-Northern New Jersey, New York Take the New Jersey Turnpike to exit 4: Camden/Philadelphia. Stay to the right though the tollbooths, take Route 73 North to Route 38 West.