Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Congress's Power Over Appropriations: Constitutional And

Congress’s Power Over Appropriations: Constitutional and Statutory Provisions June 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46417 SUMMARY R46417 Congress’s Power Over Appropriations: June 16, 2020 Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Sean M. Stiff A body of constitutional and statutory provisions provides Congress with perhaps its most Legislative Attorney important legislative tool: the power to direct and control federal spending. Congress’s “power of the purse” derives from two features of the Constitution: Congress’s enumerated legislative powers, including the power to raise revenue and “pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States,” and the Appropriations Clause. This latter provision states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” Strictly speaking, the Appropriations Clause does not provide Congress a substantive legislative power but rather constrains government action. But because Article I vests the legislative power of the United States in Congress, and Congress is therefore the moving force in deciding when and on what terms to make public money available through an appropriation, the Appropriations Clause is perhaps the most important piece in the framework establishing Congress’s supremacy over public funds. The Supreme Court has interpreted and applied the Appropriations Clause in relatively few cases. Still, these cases provide important fence posts marking the extent of Congress’s -

The American Navy by Rear-Admiral French E

:*' 1 "J<v vT 3 'i o> -< •^^^ THE AMERICAN BOOKS A LIBRARY OF GOOD CITIZENSHIP " The American Books" are designed as a series of authoritative manuals, discussing problems of interest in America to-day. THE AMERICAN BOOKS THE AMERICAN COLLEGE BY ISAAC SHARPLESS THE INDIAN TO-DAY BY CHARLES A. EASTMAN COST OF LIVING BY FABIAN FRANKLIN THE AMERICAN NAVY BY REAR-ADMIRAL FRENCH E. CHADWICK, U. S. N. MUNICIPAL FREEDOM BY OSWALD RYAN AMERICAN LITERATURE BY LEON KELLNER (translated from THB GERMAN BY JULIA FRANKLIN) SOCIALISM IN AMERICA BY JOHN MACY AMERICAN IDEALS BY CLAYTON S. COOPER THE UNIVERSITY MOVEMENT BY IRA REMSEN THE AMERICAN SCHOOL BY WALTER S. HINCHMAN THE FEDERAL RESERVE BY H. PARKER WILLIS {For more extended notice of the series, see the last pages of this book.) The American Books The American Navy By Rear-Admiral French E. Chadwick (U. S. N., Retired) GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 191S Copyright, 1915, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & CoMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, inxluding the Scandinavian m 21 1915 'CI, A 401 J 38 TO MY COMRADES OF THE NAVY PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Rear-Admiral French Ensor Chadwick was born at Morgantown, W. Va., February 29, 1844. He was appointed to the U. S. Naval Academy from West Virginia (then part of Virginia) in 1861, and graduated in November, 1864. In the summer of 1864 he was attached to the Marblehead in pursuit of the Confederate steamers Florida and Tallahassee. After the Civil War he served successively in a number of vessels, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander in 1869; was instruc- tor at the Naval Academy; on sea-service, and on lighthouse duty (i 870-1 882); Naval Attache at the American Embassy in London (1882- 1889); commanded the Yorktown (1889-1891); was Chief Intelligence Officer (1892-1893); and Chief of the Bureau of Equipment (1893-1897). -

Interactive Reader and Study Guide

Interactive Reader and Study Guide HOLT Social Studies United States History Beginnings to 1877 Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Teachers using HOLT SOCIAL STUDIES: UNITED STATES HISTORY may photocopy com- plete pages in sufficient quantities for classroom use only and not for resale. HOLT and the “Owl Design” are registered trademarks licensed to Holt, Rinehart and Winston, registered in the United States of America and/or other jurisdictions. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-03-042643-X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 082 08 07 06 05 Contents Chapter 1 The World before the Opening Chapter 8 The Jefferson Era of the Atlantic Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 66 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 1 Sec 8.1 . 67 Sec 1.1 . 2 Sec 8.2 . 69 Sec 1.2 . 4 Sec 8.3 . 71 Sec 1.3 . 6 Sec 8.4 . 73 Sec 1.4 . 8 Chapter 9 A New National Identity Chapter 2 New Empires in the Americas Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 75 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 10 Sec 9.1 . 76 Sec 2.1 . 11 Sec 9.2 . 78 Sec 2.2 . 13 Sec 9.3 . 80 Sec 2.3 . 15 Chapter 10 The Age of Jackson Sec 2.4 . 17 Chapter Opener with Graphic Organizer . 82 Sec 2.5 . -

2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities

EXPLORING THE HUMAN ENDEAVOR NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES 2ANNU0AL1 REP2ORT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER August 2013 Dear Mr. President, It is my privilege to present the 2012 Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Humanities. For forty-seven years, NEH has striven to support excellence in humanities research, education, preservation, access to humanities collections, long-term planning for educational and cultural institutions, and humanities programming for the public. NEH’s 1965 founding legislation states that “democracy demands wisdom and vision in its citizens.” Understanding our nation’s past as well as the histories and cultures of other peoples across the globe is crucial to understanding ourselves and how we fit in the world. On September 17, 2012, U.S. Representative John Lewis spoke on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial about freedom and America’s civil rights struggle, to mark the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He was joined on stage by actors Alfre Woodward and Tyree Young, and Howard University’s Afro Blue jazz vocal ensemble. The program was the culmination of NEH’s “Celebrating Freedom,” a day that brought together five leading Civil War scholars and several hundred college and high school students for a discussion of events leading up to the Proclamation. The program was produced in partnership with Howard University and was live-streamed from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History to more than one hundred “watch parties” of viewers around the nation. Also in 2012, NEH initiated the Muslim Journeys Bookshelf—a collection of twenty-five books, three documentary films, and additional resources to help American citizens better understand the people, places, history, varieties of faith, and cultures of Muslims in the United States and around the world. -

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport The Last Battle of the Revolution Less than a quarter of a century after the close of the American Revolution, Great Britain and the United States were again in conflict. Britain and her allies were engaged in a long war with Napoleonic France. The shipping-related industries of the neutral United States benefited hugely, conducting trade with both sides. Hundreds of ships, built in yards on America’s Atlantic coast and manned by American sailors, carried goods, including foodstuffs and raw materials, to Europe and the West Indies. Merchants and farmers alike reaped the profits. In Cambridge, men made plans to profit from this brisk trade. “[T]he soaring hopes of expansionist-minded promoters and speculators in Cambridge were based solidly on the assumption that the economic future of Cambridge rested on its potential as a shipping center.” The very name, Cambridgeport, reflected “the expectation that several miles of waterfront could be developed into a port with an intricate system of canals.” In January 1805, Congress designated Cambridge as a “port of delivery” and “canal dredging began [and] prices of dock lots soared." [1] Judge Francis Dana, a lawyer, diplomat, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, was one of the primary investors in the development of Cambridgeport. He and his large family lived in a handsome mansion on what is now Dana Hill. Dana lost heavily when Jefferson declared an embargo in 1807. Britain and France objected to America’s commercial relationship with their respective enemies and took steps to curtail trade with the United States. -

Alumni News & Notes

et al.: Alumni News & Notes and hosted many Homecoming Weekend here are students who maintain strong activities. "The goals of SUSA include pro T ties to Syracuse University after they viding leadership roles for students, pro graduate. Then there are students like viding career and mentoring opportuni Naomi Marcus 'o2. Just beginning her col ties for students, connecting and network lege career, she has already established a ing with Syracuse alumni, and maintain bond with the SU alumni community. ing traditions and a sense of pride in Marcus is an active member of the Syra Syracuse University," says Setek. cuse University Student Alumni Associa Danie Moss '99 says taking an active tion (SUSA}, a student volunteer organiza role in Homecoming Weekend was a mile tion sponsored by the Office of Alumni Re stone for SUSA. She and past SUSA presi lations that serves as a link between students dent Kristin Kuntz '99 saw it as a good way and the University's 22o,ooo alumni. to promote the organization. "Home For Marcus and her fellow student vol coming is a great opportunity for us to unteers, SUSA's appeal lies in its ability to interact with alumni," Moss says. "People bridge generations. "It sounded like a dif don't always realize how much they can ferent kind of organization," Marcus says. learn from other generations, so an organi "Alumni share their experiences with us, zation like this is mutually beneficial." WITH GRATITUDE AND RESPECT and we keep them up-to-date on what's Senior Alison Nathan has been pleas "Thank you"- two simple words that going on here right now. -

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress

Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Updated April 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45101 Congressional Gold Medals: Background, Legislative Process, and Issues for Congress Summary Senators and Representatives are frequently asked to support or sponsor proposals recognizing historic events and outstanding achievements by individuals or institutions. Among the various forms of recognition that Congress bestows, the Congressional Gold Medal is often considered the most distinguished. Through this venerable tradition—the occasional commissioning of individually struck gold medals in its name—Congress has expressed public gratitude on behalf of the nation for distinguished contributions for more than two centuries. Since 1776, this award, which initially was bestowed on military leaders, has also been given to such diverse individuals as Sir Winston Churchill and Bob Hope, George Washington and Robert Frost, Joe Louis and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Congressional gold medal legislation generally has a specific format. Once a gold medal is authorized, it follows a specified process for design, minting, and presentation. This process includes consultation and recommendations by the Citizens Coinage Advisory Commission (CCAC) and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), pursuant to any statutory instructions, before the Secretary of the Treasury makes the final decision on a gold medal’s design. Once the medal has been struck, a ceremony will often be scheduled to formally award the medal to the recipient. In recent years, the number of gold medals awarded has increased, and some have expressed interest in examining the gold medal authorization and awarding process. Should Congress want to make such changes, several individual and institutional options might be available. -

The United States Navy Looks at Its African American Crewmen, 1755-1955

“MANY OF THEM ARE AMONG MY BEST MEN”: THE UNITED STATES NAVY LOOKS AT ITS AFRICAN AMERICAN CREWMEN, 1755-1955 by MICHAEL SHAWN DAVIS B.A., Brooklyn College, City University of New York, 1991 M.A., Kansas State University, 1995 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2011 Abstract Historians of the integration of the American military and African American military participation have argued that the post-World War II period was the critical period for the integration of the U.S. Navy. This dissertation argues that World War II was “the” critical period for the integration of the Navy because, in addition to forcing the Navy to change its racial policy, the war altered the Navy’s attitudes towards its African American personnel. African Americans have a long history in the U.S. Navy. In the period between the French and Indian War and the Civil War, African Americans served in the Navy because whites would not. This is especially true of the peacetime service, where conditions, pay, and discipline dissuaded most whites from enlisting. During the Civil War, a substantial number of escaped slaves and other African Americans served. Reliance on racially integrated crews survived beyond the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, only to succumb to the principle of “separate but equal,” validated by the Supreme Court in the Plessy case (1896). As racial segregation took hold and the era of “Jim Crow” began, the Navy separated the races, a task completed by the time America entered World War I. -

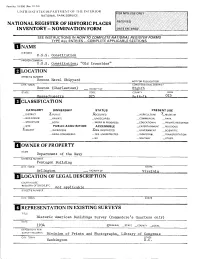

HCLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UN1TLD STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS iNAME HISTORIC U.S.S. Constitution AND/OR COMMON U.S.S. Constitution; "Old Ironsides' LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Boston Naval Shipyard .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston (Charlestown) _.VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 02S Suffolk °25 HCLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE —DISTRICT ^PUBLIC J^OCCUPiED _ AGRICULTURE ^-MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE — UNOCCUPfED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT ^RELIGIOUS X_OBJECT _|N PROCESS -XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY _OTHER: STREET& NUMBER Pentagon Building CITY. TOWN STATE Arlington VICINITY OF Virginia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC not applicable________ STREET& NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (Commodore's Quarters only) DATE ^FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY ,_LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington B.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED _ORIGINALSITE not applicable X_GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE. _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINALUF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The frigate Constitution., as designed by Joshua Humphreys and built during 1794-97, was longer, broader, and higher out of water than existing ships of her class. She had an over-all length of 204 feet and a length on the load water line of 175 feet. -

How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems?

How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems? Naval Postgraduate CRUSER Workshop April 5, 2021 George Galdorisi (Captain- U.S. Navy retired) Naval Information Warfare Center, Pacific Dr. Sam Tangredi (Captain U.S. Navy – retired) U.S. Naval War College 1 How Can We Accelerate the Insertion of Leading-Edge Technologies Into Our Military Weapons Systems? Executive Summary At the highest levels of U.S. intelligence and military policy documents, there is universal agreement that the United States remains at war, even as the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan wind down. As the cost of capital platforms—especially ships and aircraft—continues to rise, the Department of Defense is increasingly looking to procure comparatively inexpensive systems as important assets to supplement the Joint Force. As the United States builds a force structure to contend with high-end threats, it has introduced a “Third Offset Strategy” to find ways to gain an asymmetric advantage over potential adversaries. One of the key technologies embraced by this strategy is that of unmanned systems. Both the DoD and the DoN envision a future force with large numbers of relatively inexpensive unmanned systems complementing manned platforms. The U.S. military’s use of these systems—especially armed unmanned systems—is not only changing the face of modern warfare, but is also altering the process of decision-making in combat operations. These systems are evolving rapidly to deliver enhanced capability to the warfighter and seemed poised to deliver the next “revolution in military affairs.” Big data, artificial intelligence and machine learning represent some of the most cutting-edge technologies today, and will likely be the dominant technologies for the next several decades and beyond.