FSU ETD Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

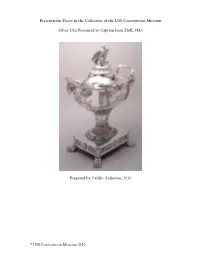

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922

Cover: During World War I, convoys carried almost two million men to Europe. In this 1920 oil painting “A Fast Convoy” by Burnell Poole, the destroyer USS Allen (DD-66) is shown escorting USS Leviathan (SP-1326). Throughout the course of the war, Leviathan transported more than 98,000 troops. Naval History and Heritage Command 1 United States Navy and World War I: 1914–1922 Frank A. Blazich Jr., PhD Naval History and Heritage Command Introduction This document is intended to provide readers with a chronological progression of the activities of the United States Navy and its involvement with World War I as an outside observer, active participant, and victor engaged in the war’s lingering effects in the postwar period. The document is not a comprehensive timeline of every action, policy decision, or ship movement. What is provided is a glimpse into how the 20th century’s first global conflict influenced the Navy and its evolution throughout the conflict and the immediate aftermath. The source base is predominately composed of the published records of the Navy and the primary materials gathered under the supervision of Captain Dudley Knox in the Historical Section in the Office of Naval Records and Library. A thorough chronology remains to be written on the Navy’s actions in regard to World War I. The nationality of all vessels, unless otherwise listed, is the United States. All errors and omissions are solely those of the author. Table of Contents 1914..................................................................................................................................................1 -

A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Sailor of King George Author: Frederick Hoffman Release Date: December 13, 2008 [Ebook 27520] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE*** [I] A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN FREDERICK HOFFMAN, R.N. 1793–1814 EDITED BY A. BECKFORD BEVAN AND H.B. WOLRYCHE-WHITMORE v WITH ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1901 [II] BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS, LONDON AND TONBRIDGE. [III] PREFACE. In a memorial presented in 1835 to the Lords of the Admiralty, the author of the journals which form this volume details his various services. He joined the Navy in October, 1793, his first ship being H.M.S. Blonde. He was present at the siege of Martinique in 1794, and returned to England the same year in H.M.S. Hannibal with despatches and the colours of Martinique. For a few months the ship was attached to the Channel Fleet, and then suddenly, in 1795, was ordered to the West Indies again. Here he remained until 1802, during which period he was twice attacked by yellow fever. The author was engaged in upwards of eighteen boat actions, in one of which, at Tiberoon Bay, St. -

Social Life in the Early Republic: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Social life in the early republic vii PREFACE peared to them, or recall the quaint figures of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and Mrs. Madison in old age, or the younger faces of Cora Livingston, Adèle Cutts, Mrs. Gardiner G. Howland, and Madame de Potestad. To those who have aided her with personal recollections or valuable family papers and letters the author makes grateful acknowledgment, her thanks being especially due to Mrs. Samuel Phillips Lee, Mrs. Beverly Kennon, Mrs. M. E. Donelson Wilcox, Miss Virginia Mason, Mr. James Nourse and the Misses Nourse of the Highlands, to Mrs. Robert K. Stone, Miss Fanny Lee Jones, Mrs. Semple, Mrs. Julia F. Snow, Mr. J. Henley Smith, Mrs. Thompson H. Alexander, Miss Rosa Mordecai, Mrs. Harriot Stoddert Turner, Miss Caroline Miller, Mrs. T. Skipwith Coles, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, and Mr. Charles Washington Coleman. A. H. W. Philadelphia, October, 1902. ix CONTENTS Chapter Page I— A Social Evolution 13 II— A Predestined Capital 42 Social life in the early republic http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.29033 Library of Congress III— Homes and Hostelries 58 IV— County Families 78 V— Jeffersonian Simplicity 102 VI— A Queen of Hearts 131 VII— The Bladensburg Races 161 VII— Peace and Plenty 179 IX— Classics and Cotillions 208 X— A Ladies' Battle 236 XI— Through Several Administrations 267 XII— Mid-Century Gayeties 296 xi ILLUSTRATIONS Page Mrs. Richard Gittings, of Baltimore (Polly Sterett) Frontispiece From portrait by Charles Willson Peale, owned by her great-grandson, Mr. D. Sterett Gittings, of Baltimore. Mrs. Gittings eyes are dark brown, the hair dark brown, with lighter shades through it; the gown of delicate pink, the sleeves caught up with pearls, the sash of a gray shade. -

Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS THE FEDERAL LIBRARY AND BICENTENNIAL INFORMATION CENTER 1800 - 2000 COMMITTEE American Federal Libraries/Information Centers Chronology 1780 Military garrison at West Point establishes library by assessing officers at the rate of one day’s pay per month to purchase books—arguably the first federal library since it existed when the country was founded (predecessor to U.S. Military Academy Library) 1789 First official federal library established at the Department of State 1795 War Department Library established in Philadelphia as a general historical military library by Henry Knox, the first Secretary of War 1800 The Navy Department Library established on March 31 by direction of President John Adams to Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert 1800 Library of Congress (LoC) founded on April 24 1800 War Department Library collections destroyed in fire at War Office Building on November 8, soon after relocation to Washington 1802 The President and Vice President authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Supreme Court Justices authorized to use LoC collections 1812 Congress appropriates $50,000 for the procurement of instruments and books for Coast Survey 1814 British burn both State Department Library and LoC collections during War of 1812 1815 Congress purchases Thomas Jefferson’s private library to replace LoC collections and opens collections to the general public 1817 Earliest documentation of book purchasing for Department of Treasury library 1820 Army Surgeon General James Lovell establishes office collection of books -

World War I Context Follow up in 1915, Europe Was Embroiled in U.S

1915: World War I Context Follow Up In 1915, Europe was embroiled in U.S. newspapers aroused outrage war, but U.S. public sentiment op- against Germany for ruthlessly kill- posed involvement. President ing defenceless Americans. The U.S. Woodrow Wilson said they would was being drawn into the war. In “remain neutral in fact as well as in June 1916, Congress increased the name.”23 size of the army. In September, Con- gress allocated $7 billion for national Pretext Incident defense, “the largest sum appropri- On May 7, 1915, a German subma- ated to that time.”30 rine (U-boat) sank the Lusitania, a In January 1917, the British British passenger ship killing 1,198, said they had intercepted a German including 128 Americans.24 message to Mexico seeking an alli- The public was not told that ance with Germany and offering to passengers were, in effect, a ‘human help Mexico recover land ceded to shield’ protecting six million rounds the U.S. On April 2, Wilson told of U.S. ammunition bound for Brit- Congress: “The world must be safe ain.25 To Germany, the ship was a for democracy.” Four days later the threat. To Britain, it was bait for lur- U.S. declared war on Germany.31 ing an attack. Why? A week before the attack, Real Reasons British Admiralty leader, Winston The maneuvre which brings Influential British military, political Churchill wrote to the Board of an ally into the field is as and business interests wanted U.S. Trade’s president saying it is “most serviceable as that which help in their war with Germany. -

Hornblower's Ships

Names of Ships from the Hornblower Books. Introduction Hornblower’s biographer, C S Forester, wrote eleven books covering the most active and dramatic episodes of the life of his subject. In addition, he also wrote a Hornblower “Companion” and the so called three “lost” short stories. There were some years and activities in Hornblower’s life that were not written about before the biographer’s death and therefore not recorded. However, the books and stories that were published describe not only what Hornblower did and thought about his life and career but also mentioned in varying levels of detail the people and the ships that he encountered. Hornblower of course served on many ships but also fought with and against them, captured them, sank them or protected them besides just being aware of them. Of all the ships mentioned, a handful of them would have been highly significant for him. The Indefatigable was the ship on which Midshipman and then Acting Lieutenant Hornblower mostly learnt and developed his skills as a seaman and as a fighting man. This learning continued with his experiences on the Renown as a lieutenant. His first commands, apart from prizes taken, were on the Hotspur and the Atropos. Later as a full captain, he took the Lydia round the Horn to the Pacific coast of South America and his first and only captaincy of a ship of the line was on the Sutherland. He first flew his own flag on the Nonsuch and sailed to the Baltic on her. In later years his ships were smaller as befitted the nature of the tasks that fell to him. -

CHAINING the HUDSON the Fight for the River in the American Revolution

CHAINING THE HUDSON The fight for the river in the American Revolution COLN DI Chaining the Hudson Relic of the Great Chain, 1863. Look back into History & you 11 find the Newe improvers in the art of War has allways had the advantage of their Enemys. —Captain Daniel Joy to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, January 16, 1776 Preserve the Materials necessary to a particular and clear History of the American Revolution. They will yield uncommon Entertainment to the inquisitive and curious, and at the same time afford the most useful! and important Lessons not only to our own posterity, but to all succeeding Generations. Governor John Hancock to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, September 28, 1781. Chaining the Hudson The Fight for the River in the American Revolution LINCOLN DIAMANT Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ii retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation: printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson : the fight for the river in the American Revolution / Lincoln Diamant.—Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Carol Pub. Group, 1994. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 (pbk.) 1. New York (State)—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 2. United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 3. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. -

Alumni News & Notes

et al.: Alumni News & Notes and hosted many Homecoming Weekend here are students who maintain strong activities. "The goals of SUSA include pro T ties to Syracuse University after they viding leadership roles for students, pro graduate. Then there are students like viding career and mentoring opportuni Naomi Marcus 'o2. Just beginning her col ties for students, connecting and network lege career, she has already established a ing with Syracuse alumni, and maintain bond with the SU alumni community. ing traditions and a sense of pride in Marcus is an active member of the Syra Syracuse University," says Setek. cuse University Student Alumni Associa Danie Moss '99 says taking an active tion (SUSA}, a student volunteer organiza role in Homecoming Weekend was a mile tion sponsored by the Office of Alumni Re stone for SUSA. She and past SUSA presi lations that serves as a link between students dent Kristin Kuntz '99 saw it as a good way and the University's 22o,ooo alumni. to promote the organization. "Home For Marcus and her fellow student vol coming is a great opportunity for us to unteers, SUSA's appeal lies in its ability to interact with alumni," Moss says. "People bridge generations. "It sounded like a dif don't always realize how much they can ferent kind of organization," Marcus says. learn from other generations, so an organi "Alumni share their experiences with us, zation like this is mutually beneficial." WITH GRATITUDE AND RESPECT and we keep them up-to-date on what's Senior Alison Nathan has been pleas "Thank you"- two simple words that going on here right now. -

USS Constitution Vs. HMS Guerriere

ANTICIPATION 97 Anticipation What do sailors feel as they wait for battle to begin? Fear – Sailors worry that they or their friends might not survive the battle. What frightens you? Excitement – The adrenaline pumps as the moment the sailors have been training for arrives. How do you feel when something you’ve waited for is about to happen? Anxiety – Sailors are nervous because no one knows the outcome of the battle. What makes you anxious? Illustration from the sketchbook of Lewis Ashfield Kimberly, 1857-1860 Kimberly was Lieutenant on board USS Germantown in the 1850s Collection of the USS Constitution Museum, Boston 98 Gun Crew’s Bible As sailors waited for battle to begin, they were alone with their thoughts. They had time to dwell on the fear that they might never see their families again. Some gun crews strapped a Bible like this one to their cannon’s carriage for extra protection. Bible issued by the Bible Society of Nassau Hall, Princeton, New Jersey Bible was strapped to the carriage of a gun nicknamed “Montgomery” on board USS President, 1813 Collection of the USS Constitution Museum, Boston 99 ENGAGEMENT 100 What are the characteristics of a brave sailor? Courage – Sailors push fear aside to do their job. What have you done that took courage? Responsibility – Each sailor has to do his duty to his country, ship, and shipmates. What are your responsibilities to your community, school, or family? Team Player – Working together is critical to succeed in battle. How do you work or play as part of a team? 101 Engagement USS Constitution vs. -

The Life of Silas Talbot, a Commodore in the Navy of the United States

•' %/ .i o LIFE OF TALBOT THE LIFE OF SILAS TALBOT COMMODORE IN THE NAVY OF THE UNITED STATES, BY HENRY T. TUCKERMAN. NEW-YORK: I C. RIKER, 129 FULTON-STREET. 1850. ETgoT Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1850, by H. T. TUCKERMAN, in the Clerk's Office of the Southern District of New-York. John F. Trow, Printer, 49 Ann-st., N. Y. PREFACE The following memoir was intended for the series of American Biography edited by- President Sparks. Owing to the suspension of that valuable work, and at the suggestion of its accomplished editor, the present sketch appears in a separate volume. In preparing it, I have been actuated by a desire to ren- der justice to a highly efficient and patriotic American officer, and, at the same time, to preserve some of the incidents and corre- spondence which belong to that period of our country's annals, to which the flight of time only adds new significance and interest. There has been manifest, until within a few 1* VI PREFACE. years, a singular indifference to the histori- cal and biographical details of our revolu- tionary era ; and an absence of that cordial recognition of individual merit in some of the chief actors of that great drama, which confirm, not only the proverbial charge of ingratitude against republics, but justify De Tocqueville's theory with regard to their exclusive devotion to the immediate, and their peculiar insensibility to the lessons of the past. The difficulty experienced in ob- taining many of the facts in this brief and imperfect sketch, as well as the original documents requisite to authenticate them, is sufficient evidence of the forgetfulness and neglect to which the records of American public characters are liable. -

Defeating the U-Boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 36 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Defeating the U-boat Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT S NA N E V ES AV T AT A A A L L T T W W S S A A D D R R E E C C T T I I O O L N L N L L U U E E E E G G H H E E T T I I VIRIBU VOIRRIABU OR A S CT S CT MARI VI MARI VI 36 Jan S. Breemer Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE This perspective aerial view of Newport, Rhode Island, drawn and published by Galt & Hoy of New York, circa 1878, is found in the American Memory Online Map Collections: 1500–2003, of the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C. The map may be viewed at http://hdl.loc.gov/ loc.gmd/g3774n.pm008790. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. ISBN 978-1-884733-77-2 is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Govern- ment Printing Office requests that any reprinted edi- tion clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Defeating the U- boat: Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare, by Jan S.