Autumn 2007 Full Issue the .SU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

European Electronic Cigarette & Vaporizer Market

EUROPEAN ELECTRONIC CIGARETTE & VAPORIZER MARKET Size, Share, Analysis & Forecast: 2015-2025 European Electronic Cigarette & E Vapor Market Size, Share, Analysis & Forecast: 2015-2025 BIS Research is a leading market intelligence and technology research company. BIS Research publishes in-depth market intelligence reports focusing on the market estimations, technology analysis, emerging high-growth applications, deeply segmented granular country-level market data and other important market parameters useful in the strategic decision making for senior management. BIS Research provides multi-client reports, company profiles, databases, and custom research services. Copyright © 2015 BIS Research All Rights Reserved. This document contains highly confidential information and is the sole property of BIS Research. Disclosing, copying, circulating, quoting or otherwise reproducing any or all contents of this document is strictly prohibited. Access to this information is provided exclusively for the benefit of the people or organization concerned. It may not be accessed by, or offered whether for sale or otherwise to any third party. BIS Research Sample Pages 2 European Electronic Cigarette & E Vapor Market Size, Share, Analysis & Forecast: 2015-2025 1 E-CIGARETTE MARKET DYNAMICS 1.1 INTRODUCTION The market dynamics section of the report examines the diverse factors which govern the production and consumption of e-cigarettes in the European market. This analysis will provide an in-depth understanding of the direction in which the market is headed and the impacts of various factors on it. This section covers the market dynamics – namely the drivers, challenges, and the opportunities in the electronic cigarette market, listing and analyzing several factors that positively and negatively affect it. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Alternative Naval Force Structure

Alternative Naval Force Structure A compendium by CIMSEC Articles By Steve Wills · Javier Gonzalez · Tom Meyer · Bob Hein · Eric Beaty Chuck Hill · Jan Musil · Wayne P. Hughes Jr. Edited By Dmitry Filipoff · David Van Dyk · John Stryker 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................ 3 The Perils of Alternative Force Structure ................................................... 4 By Steve Wills UnmannedCentric Force Structure ............................................................... 8 By Javier Gonzalez Proposing A Modern High Speed Transport – The Long Range Patrol Vessel ................................................................................................... 11 By Tom Meyer No Time To Spare: Drawing on History to Inspire Capability Innovation in Today’s Navy ................................................................................. 15 By Bob Hein Enhancing Existing Force Structure by Optimizing Maritime Service Specialization .............................................................................................. 18 By Eric Beaty Augment Naval Force Structure By Upgunning The Coast Guard .......................................................................................................... 21 By Chuck Hill A Fleet Plan for 2045: The Navy the U.S. Ought to be Building ..... 25 By Jan Musil Closing Remarks on Changing Naval Force Structure ....................... 31 By Wayne P. Hughes Jr. CIMSEC 22 www.cimsec.org -

Military History Anniversaries 16 Thru 30 November

Military History Anniversaries 16 thru 30 November Events in History over the next 15 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: British and Hessian units capture Fort Washington from the Patriots. Nearly 3,000 Patriots were taken prisoner, and valuable ammunition and supplies were lost to the Hessians. The prisoners faced a particularly grim fate: Many later died from deprivation and disease aboard British prison ships anchored in New York Harbor. Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: The United Provinces (Low Countries) recognize the independence of the United States. Nov 16 1776 – American Revolution: The first salute of an American flag (Grand Union Flag) by a foreign power is rendered by the Dutch at St. Eustatius, West Indies in reply to a salute by the Continental ship Andrew Doria. Nov 16 1798 – The warship Baltimore is halted by the British off Havana, intending to impress Baltimore's crew who could not prove American citizenship. Fifty-five seamen are imprisoned though 50 are later freed. Nov 16 1863 – Civil War: Battle of Campbell's Station near Knoxville, Tennessee - Confederate troops unsuccessfully attack Union forces. Casualties and losses: US 316 - CSA 174. Nov 16 1914 – WWI: A small group of intellectuals led by the physician Georg Nicolai launch Bund Neues Vaterland, the New Fatherland League in Germany. One of the league’s most active supporters was Nicolai’s friend, the great physicist Albert Einstein. 1 Nov 16 1941 – WWII: Creed of Hate - Joseph Goebbels publishes in the German magazine Das Reich that “The Jews wanted the war, and now they have it”—referring to the Nazi propaganda scheme to shift the blame for the world war onto European Jewry, thereby giving the Nazis a rationalization for the so-called Final Solution. -

Headmark 010 Nov 1977

JOURNAL OF tTHE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE VOLUME 3 NOVEMBER 1977 NUMBER 4 AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE 1. The Australian Naval Institute has been formed and incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory. The main objects of the Institute are: — a. to encourage and promote the advancement of knowledge related to the Navy and the Maritime profession. b. to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas concerning subjects related to the Navy and the Maritime profession. c. to publish a journal. 2. The Institute is self supporting and non-profit making. The aim is to encourage freedom of dis- cussion, dissemination of information, comment and opinion and the advancement of professional knowledge concerning naval and maritime matters. 3. Membership of the Institute is open to:— a. Regular Members—Members of the Permanent Naval Forces of Australia. b. Associate Members-! 1) Members of the Reserve Naval Forces of Australia. (2) Members of the Australian Military Forces and the Royal Australian Air Force both permanent and reserve. (3) Ex-members of the Australian Defence Forces, both permanent and reserve components, provided that they have been honourably discharged from that force. (4) Other persons having and professing a special interest in naval and maritime affairs. c. Honorary Members—A person who has made a distinguished contribution to the Naval or maritime profession or who has rendered distinguished service to the Institute may be elected by the Council to Honorary Membership. 4. Joining fee for Regular and Associate Member is $5. Annual Subscription for both is $10. 5. Inquiries and application for membership should be directed to:— The Secretary, Australian Naval Institute, P.O. -

FY 2020 Announcement.Pdf

17 February 2021 –PRELIMINARY RESULTS BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO p.l.c. YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 ‘ACCELERATING TRANSFORMATION’ GROWTH IN NEW CATEGORIES AND GROUP EARNINGS DESPITE COVID-19 PERFORMANCE HIGHLIGHTS REPORTED ADJUSTED Current Vs 2019 Current Vs 2019 rates Rates (constant) Cigarette and THP volume share +30 bps Cigarette and THP value share +20 bps Non-Combustibles consumers1 13.5m +3.0m Revenue (£m) £25,776m -0.4% £25,776m +3.3% Profit from operations (£m) £9,962m +10.5% £11,365m +4.8% Operating margin (%) +38.6% +380 bps +44.1% +100 bps2 Diluted EPS (pence) 278.9p +12.0% 331.7p +5.5% Net cash generated from operating activities (£m) £9,786m +8.8% Free cash flow after dividends (£m) £2,550m +32.7% Cash conversion (%)2 98.2% -160 bps 103.0% +650 bps Borrowings3 (£m) £43,968m -3.1% Adjusted Net Debt (£m) £39,451m -5.3% Dividend per share (pence) 215.6p +2.5% The use of non-GAAP measures, including adjusting items and constant currencies, are further discussed on pages 48 to 53, with reconciliations from the most comparable IFRS measure provided. Note – 1. Internal estimate. 2. Movement in adjusted operating margin and operating cash conversion are provided at current rates. 3. Borrowings includes lease liabilities. Delivering today Building A Better TomorrowTM • Revenue, profit from operations and earnings • 1 growth* absorbing estimated 2.5% COVID-19 revenue 13.5m consumers of our non-combustible products , headwind adding 3m in 2020. On track to 50m by 2030 • New Categories revenue up 15%*, accelerating • Combustible revenue -

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut

Scott Wadsworth Heaney Member, Board of Directors World Affairs Council of Connecticut Scott Wadsworth Heaney was born in Hartford Connecticut on June 3, 1973 and was raised in Glastonbury, Connecticut where he graduated from Glastonbury High School in 1992. From 1992-1996, Scott attended Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts earning a Bachelors of Science Degree in Psychology. While at Springfield College, Scott was the Student assistant to the Director of Alumni Relations, was a member of both the track and cross country teams, and was involved in numerous extra curricular activities on and off campus. Scott was also a founding member of the Springfield College Student Alumni Council and the Springfield College Veteran’s Day Committee. In 1993, Scott was accepted into the Marine Corps Platoon Leader’s Class Officer Candidate Program. Upon graduation, he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps. In September 1996, he reported to the Marine Corps Combat Development Command in Quantico, Virginia for The Basic School (TBS), a grueling six month officer development program which all Marine Corps officers must complete after after becoming a commissioned officer. Having graduated from the Basic Logistics Officer’s Course, The Landing Force Logistics Officers Course and the Joint Maritime Pre-positioned Force Staff Planner’s Course, Scott became a logistics officer and was assigned to his first duty station in California. In 1998, Scott reported to First Marine Corps Division in Camp Pendleton California to serve in the infantry battalion as the Assistant Logistics Officer for First Battalion First Marines (1/1). During his tour from 1999-2000, Scott’s battalion completed a six month deployment on the USS Peleliu operating in Korea, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and conducting peace keeping operations in East Timor. -

Spring 2003 Vol

ISSN 1536-4003 University of California, Berkeley Center forSlavic and East European Studies Newsletter Notes from the Director Spring 2003 Vol. 20, No. 1 In these unsettled times, it behooves us more than ever to understand the In this issue: causes and consequences of violence inflicted by extremist groups. The Notes from the Director .....................1 United States is not alone in facing profound challenges following the Bear Treks ........................................2 terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Like us, our West European allies are Berkeley-Stanford Conference ...........3 struggling to find a reasonable balance between respect for civil liberties Spring Courses .................................4 and freedom of expression on the one hand and the need to protect society Michael Carpenter from acts of terrorism carried out in the name of extremist ideologies. So, too, The Modern Slave Trade in is Russia wrestling with these issues, as highlighted most dramatically by Post-Communist Europe ...................5 the ongoing violence and human rights abuses being perpetrated by federal Michael Kunichika forces in Chechnya, as well as human rights violations and acts of terrorism A Window On the Lake: On and by the Chechen resistance, such as the recent hostage-taking incident in Around Stalin's Belomorkanal ...........9 Moscow. Nor should it be assumed that the only extremist challenge in Campus Visitors ............................. 16 Russia, or indeed elsewhere, comes from Islamist extremists. As Vladimir Christine Kulke Putin put it in his state of the nation address on April 18, 2002: “The growth Book Review: Historical Atlas of of extremism presents a serious threat to stability and public safety in our Central Europe ............................... -

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

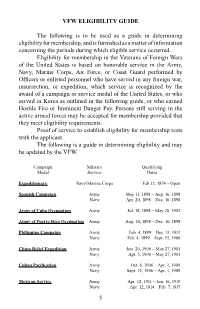

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

137733NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. -.. ~ r---~~~--------' • Thru: 3/31/92 U.S. COAST GUARD \ " DIGEST OF LAW ENFORCEMENT ~. L STATISTICS Compiled by (G-OLE -1 ) I I!:'::l, , L~.~Jr CJ" If"\i. .§J~ ;J f I I. '-----_________----1 II I The U.S. Coast Guard's General Digest of Law Enforcement Statistics is published semi-annually. It is distributed primarily within the Coast Guard. It is, however, provided to interested agencies and individuals on request. • This booklet represents the most recent information available for the reported period. Some changes may occasionally be noted for prior year information as cases are reviewed and updated. The information presented herein is compiled, reviewed, and promulgated by the Operational Law Enforcement Division of U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters. To provide comments or ask questions please call (202) 267-1766 (FTS callers use same number without area code). To aid the reader in corresponding with this office, our mailing address is provided below: Commandant (G-OLE-1) USCG Headquarters Room 3110 2100 2nd Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20593-0001 • 137733 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Po in Is of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this nqa '1'%1 material has been granted by U.S. Coast GJard~ ___________ to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS).