The 1812 Streets of Cambridgeport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

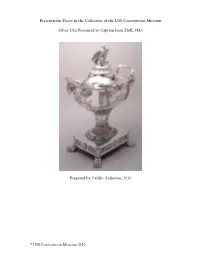

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

1 Overview of USS Constitution Re-Builds & Restorations USS

Overview of USS Constitution Re-builds & Restorations USS Constitution has undergone numerous “re-builds”, “re-fits”, “over hauls”, or “restorations” throughout her more than 218-year career. As early as 1801, she received repairs after her first sortie to the Caribbean during the Quasi-War with France. In 1803, six years after her launch, she was hove-down in Boston at May’s Wharf to have her underwater copper sheathing replaced prior to sailing to the Mediterranean as Commodore Edward Preble’s flagship in the Barbary War. In 1819, Isaac Hull, who had served aboard USS Constitution as a young lieutenant during the Quasi-War and then as her first War of 1812 captain, wrote to Stephen Decatur: “…[Constitution had received] a thorough repair…about eight years after she was built – every beam in her was new, and all the ceilings under the orlops were found rotten, and her plank outside from the water’s edge to the Gunwale were taken off and new put on.”1 Storms, battle, and accidents all contributed to the general deterioration of the ship, alongside the natural decay of her wooden structure, hemp rigging, and flax sails. The damage that she received after her War of 1812 battles with HMS Guerriere and HMS Java, to her masts and yards, rigging and sails, and her hull was repaired in the Charlestown Navy Yard. Details of the repair work can be found in RG 217, “4th Auditor’s Settled Accounts, National Archives”. Constitution’s overhaul of 1820-1821, just prior to her return to the Mediterranean, saw the Charlestown Navy Yard carpenters digging shot out of her hull, remnants left over from her dramatic 1815 battle against HMS Cyane and HMS Levant. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

Thomas Wilkey Journal on Board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey

Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 22, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Library Company of Philadelphia 2012 March 10 Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 - Page 2 - Thomas Wilkey journal on board the U.S.S. Delaware LCP.Wilkey Summary Information Repository Library Company of Philadelphia Creator Wilkey, Thomas Title Thomas Wilkey journal -

The American Navy by Rear-Admiral French E

:*' 1 "J<v vT 3 'i o> -< •^^^ THE AMERICAN BOOKS A LIBRARY OF GOOD CITIZENSHIP " The American Books" are designed as a series of authoritative manuals, discussing problems of interest in America to-day. THE AMERICAN BOOKS THE AMERICAN COLLEGE BY ISAAC SHARPLESS THE INDIAN TO-DAY BY CHARLES A. EASTMAN COST OF LIVING BY FABIAN FRANKLIN THE AMERICAN NAVY BY REAR-ADMIRAL FRENCH E. CHADWICK, U. S. N. MUNICIPAL FREEDOM BY OSWALD RYAN AMERICAN LITERATURE BY LEON KELLNER (translated from THB GERMAN BY JULIA FRANKLIN) SOCIALISM IN AMERICA BY JOHN MACY AMERICAN IDEALS BY CLAYTON S. COOPER THE UNIVERSITY MOVEMENT BY IRA REMSEN THE AMERICAN SCHOOL BY WALTER S. HINCHMAN THE FEDERAL RESERVE BY H. PARKER WILLIS {For more extended notice of the series, see the last pages of this book.) The American Books The American Navy By Rear-Admiral French E. Chadwick (U. S. N., Retired) GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 191S Copyright, 1915, by DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & CoMPANY All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, inxluding the Scandinavian m 21 1915 'CI, A 401 J 38 TO MY COMRADES OF THE NAVY PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Rear-Admiral French Ensor Chadwick was born at Morgantown, W. Va., February 29, 1844. He was appointed to the U. S. Naval Academy from West Virginia (then part of Virginia) in 1861, and graduated in November, 1864. In the summer of 1864 he was attached to the Marblehead in pursuit of the Confederate steamers Florida and Tallahassee. After the Civil War he served successively in a number of vessels, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander in 1869; was instruc- tor at the Naval Academy; on sea-service, and on lighthouse duty (i 870-1 882); Naval Attache at the American Embassy in London (1882- 1889); commanded the Yorktown (1889-1891); was Chief Intelligence Officer (1892-1893); and Chief of the Bureau of Equipment (1893-1897). -

University of California

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The United States and the Barbary Pirates: Adventures in Sexuality, State-Building, and Nationalism, 1784-1815 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jason Raphael Zeledon Committee in charge: Professor Patricia Cohen, co-chair Professor John Majewski, co-chair Professor Salim Yaqub Professor Mhoze Chikowero June 2016 The dissertation of Jason Raphael Zeledon is approved ______________________________________________ Mhoze Chikowero ______________________________________________ Salim Yaqub ______________________________________________ Patricia Cohen, Committee Co-Chair ______________________________________________ John Majewski, Committee Co-Chair June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my eleventh-grade American History teacher, Peggy Ormsby. If I had not taken her AP class, my life probably would have gone in a different direction! At that time math was my favorite subject, but her class got me hooked on studying American History. Thanks, too, to the excellent teachers and mentors in graduate school who shaped and challenged my thinking. At American University (where I earned my M.A.), I’d like to thank Max Friedman, Andrew Lewis, Kate Haulman, and Eileen Findlay. I transferred to UCSB to finish my Ph.D. and have thoroughly enjoyed working with Pat Cohen, John Majewski, Salim Yaqub, and Mhoze Chikowero. I’d especially like to thank Pat, who provided insightful feedback on early drafts of my chapter about the Mellimelli mission (which has been published in Diplomatic History). Additionally, I’d like to thank UCSB’s History, Writing, and English Departments for providing Teaching Assistantships and the staffs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library of Congress Manuscript Reading Room, and the Huntington Library for their help and friendliness. -

War of 1812 Travel Map & Guide

S u sq u eh a n n a 1 Westminster R 40 r e iv v e i r 272 R 15 anal & Delaware C 70 ke Chesapea cy a Northeast River c o Elk River n 140 Havre de Chesapeake o 97 Grace City 49 M 26 40 Susquehanna 213 32 Flats 301 13 795 95 1 r e Liberty Reservoir v i R Frederick h 26 s 9 u B 695 Elk River G 70 u 340 n Sa p ssaf 695 rass 83 o Riv w er r e d 40 e v i r R R Baltimore i 13 95 v e r y M c i 213 a dd c le o B R n 70 ac iv o k e R r M 270 iv e 301 r P o to m ac 15 ster Che River 95 P 32 a R t i v a 9 e r p Chestertown 695 s 13 co R 20 1 i 213 300 1 ve r 100 97 Rock Hall 8 Leesburg 97 177 213 Dover 2 301 r ive r R e 32 iv M R 7 a r k got n hy te Ri s a v t 95 er e 295 h r p 189 S e o e C v 313 h ve i r C n R R e iv o er h 13 ka 267 495 uc 113 T Whitehall Bay Bay Bridge 50 495 Greensboro 193 495 Queen Milford Anne 7 14 50 Selby 404 Harrington Bay 1 14 Denton 66 4 113 y P 258 a a B t u rn 404 x te 66 Washington D.C. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842)

An Incomplete History of the USS FISKE (DD/DDR 842) For The Fiske Association Prepared by R. C. Mabe – Association Historian October 1999 Edited & revised by G. E. Beyer – Association Historian September 2007 Introduction The USS FISKE was a Gearing Class destroyer, the last of the World War II design destroyers. She served in the US Navy from 1945 until 1980 and was subsequently transferred to the Turkish Navy where she served as the TCG Piyale Pasa (D350). The former FISKE was heavily damaged in 1996 when she ran aground and was scrapped in early 1999. Altogether the FISKE served two navies for over 54 years. I am titling this report as an „Incomplete History of the USS Fiske DD/DDR 842‟ for the simple reason that it not complete. I am continuing to try and fill the gaps and inconsistencies to the best of my ability. Any help in this effort will be appreciated. The Soul of a Ship Now, some say that men make a ship and her fame As she goes on her way down the sea: That the crew which first man her will give her a name – Good, bad, or whatever may be. Those coming after fall in line And carry the tradition along – If the spirit was good, it will always be fine – If bad, it will always be wrong/ The soul of a ship is a marvelous thing. Not made of its wood or its steel, But fashioned of mem‟ries and songs that men sing, And fed by the passions men feel. -

The Best Musical in Recent History Seniors Come Together at Cape

The WALRUS The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things: Of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings. - Lewis Carroll Vol LXVIII No. 2 St. Sebastian’s School November 2014 The Best Musical in Recent History By Pat McGowan ‘15 is the leader of a Christian Mission being tipped off about the crap game Band that travels around New York which would end with his arrest for il- HEAD WRITER City looking for sinners to convert to legal underground gambling. Eventu- The St. Sebastian’s Drama Christianity by the Word of God, so ally, Nathan could no longer juggle all Club presented the musical Guys and it would be hard for Sky to woo her these things and his fiancé Adelaide Dolls for the annual fall play this year. into going to Cuba with him so he discovered he was still formulating Led by faculty members Mr. Rogers, could win the bet. Well, Sky worked secret crap games and vowed to never Mrs. Stansfield, and Mr. Grohmann, his magic and convinced Miss Sarah talk to him ever again. Guys and Dolls was a big hit this to accompany him to Havana. At first, At the end of the crap game, year. Auditions were set for late May Sky figured this would just be another in order to save his relationship with because the cast members wanted to girl but the more time he spent with Sarah, Sky Masterson offers each one get a head start on learning the dif- her the more he fell in love with her; of the gamblers a bet that says if he ficult music the play consists of. -

Commodore Perry Farm

Th r.r, I C. *. 1 4 7. tj,vi:S t,’J !.&:-r;JO v . I / jL. Lii . ; United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic PAaces ...received lnventory-Nomnation Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Commodore Perry Farm and/orcommon Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry Birthplace, "The Commodore" 2. Location street & number 184 Post Road - not for publication #2 - Hon. Claudine Schneider city, town South Kings town N ..A vicinity of Cunt.cnoionnl dist4ot state Rhode Island code 44 county Washington code 009 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public i occupied agriculture museum -.JL. buildings .L.. private unoccupied commercial - park structure both work in progress - educational ..._L private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object ?LAJn process ......X yes: restricted government scientific being considered -- yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Mrs. Wisner Townsend street&number 184 Post Road city, town Wake field PLA.vicinity of state Rhode Island 02880 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Town Clerk, South Kingstown Town i-Jail - street & number 111gb Street city, town Wakefield state Rhode is land 02880 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See Continuation Sheet #1. has this property been determined eligible? yes ç4ç_ no date - federal .... state county - local depository for survey records city, town state NP Form I0.900.h OMEI No.1074-0018 .‘‘‘‘‘.t3.82 Eq, 1031-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For Nt’S use on’y t’lationa! Register of Historic Places received’ lnventory-Nominatñon Form dateentéred Continuation sheet 1 *, item number , Page 2 Historic American Bui ] clings Survey 1956, 1959 Library of Congress Washington, D.C.