Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Gloucester Community Preservation Committee

CITY OF GLOUCESTER COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE BUDGET FORM Project Name: Masonry and Palladian Window Preservation at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Applicant: Historic New England SOURCES OF FUNDING Source Amount Community Preservation Act Fund $10,000 (List other sources of funding) Private donations $4,000 Historic New England Contribution $4,000 Total Project Funding $18,000 PROJECT EXPENSES* Expense Amount Please indicate which expenses will be funded by CPA Funds: Masonry Preservation $13,000 CPA and Private donations Window Preservation $2,200 Historic New England Project Subtotal $15,200 Contingency @10% $1,520 Private donations and Historic New England Project Management $1,280 Historic New England Total Project Expenses $18,000 *Expenses Note: Masonry figure is based on a quote provided by a professional masonry company. Window figure is based on previous window preservation work done at Beauport by Historic New England’s Carpentry Crew. Historic New England Beauport, The Sleeper-McCann House CPA Narrative, Page 1 Masonry Wall and Palladian Window Repair Historic New England respectfully requests a $10,000 grant from the City of Gloucester Community Preservation Act to aid with an $18,000 project to conserve a portion of a masonry wall and a Palladian window at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a National Historic Landmark. Project Narrative Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, was the summer home of one of America’s first professional interior designers, Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934). Sleeper began constructing Beauport in 1907 and expanded it repeatedly over the next twenty-seven years, working with Gloucester architect Halfdan M. -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

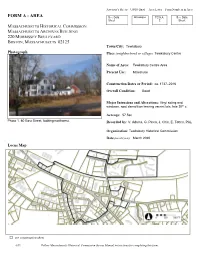

FORM a - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet

Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area FORM A - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Town/City: Tewksbury Photograph Place (neighborhood or village): Tewksbury Centre Name of Area: Tewksbury Centre Area Present Use: Mixed use Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1737–2016 Overall Condition: Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: Vinyl siding and windows, spot demolition leaving vacant lots, late 20th c. Acreage: 57.5ac Photo 1. 60 East Street, looking northwest. Recorded by: V. Adams, G. Pineo, J. Chin, E. Totten, PAL Organization: Tewksbury Historical Commission Date (month/year): March 2020 Locus Map ☐ see continuation sheet 4/11 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET TEWKSBURY TEWKSBURY CENTRE AREA MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 TEW.A, E See Data Sheet ☒ Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Tewksbury Centre Area (TEW.A), the civic and geographic heart of Tewksbury, encompasses approximately 58 buildings across 57.5 acres centered on the Tewksbury Common at the intersection of East, Pleasant, and Main streets and Town Hall Avenue. Tewksbury Centre has a concentration of civic, institutional, commercial, and residential buildings from as early as ca. 1737 through the late twentieth century; mid-twentieth-century construction is generally along smaller side streets on the outskirts of the Tewksbury Centre Area. -

Bischof Associate Professor of History and Chair Department of History and Political Science, University of Southern Maine

Elizabeth (Libby) Bischof Associate Professor of History and Chair Department of History and Political Science, University of Southern Maine 200G Bailey Hall 59 Underhill Dr. 37 College Ave. Gorham, Maine 04038 Gorham, Maine 04038 Cell: 617-610-8950 [email protected] [email protected] (207) 780-5219 Twitter: @libmacbis EMPLOYMENT: Associate Professor of History, with tenure, University of Southern Maine, 2013-present. Assistant Professor of History, University of Southern Maine, 2007-2013. Post-Doctoral Fellow, Boston College, 2005-2007. EDUCATION: August 2005 Ph.D., American History, Boston College. Dissertation: Against an Epoch: Boston Moderns, 1880-1905 November 2001 Master of Arts, with distinction, History, Boston College May 1999 Bachelor of Arts, cum laude, History, Boston College RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS: Nineteenth-century US History (Cultural/Social) American Modernism History of Photography/Visual Culture Artist Colonies/Arts and Crafts Movement New England Studies/Maine History Popular Culture/History and New Media PUBLICATIONS: Works in Progress/Forthcoming: Libby Bischof, Susan Danly, and Earle Shettleworth, Jr. Maine Photography: A History, 1840-2015 (Forthcoming, Down East Books/Rowman & Littlefield and the Maine Historical Society, Fall 2015). “A Region Apart: Representations of Maine and Northern New England in Personal Film, 1920-1940,” in Martha McNamara and Karan Sheldon, eds., Poets of Their Own Acts: The Aesthetics of Home Movies and Amateur Film (Forthcoming, Indiana University Press). Modernism and Friendship in 20th Century America (current book project). Books: (With Susan Danly) Maine Moderns: Art in Seguinland, 1900-1940 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011). Winner, 2013 New England Society Book Award for Best Book in Art and Photography Peer-Reviewed Articles/Chapters in Scholarly Books: “Who Supports the Humanities in Maine? The Benefits (and Challenges) of Volunteerism,” forthcoming from Maine Policy Review: Special Issue on the Humanities and Policy, Vol. -

James Bowdoin: Patriot and Man of the Enlightenment (Pamphlet)

JAMES BOWDOIN N COLLEGE May 2 8 — September i 2 1976 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/jannesbowdoinpatrOObowd_0 JAMES BOWDOIN Patriot and Man of The Enlightenment JAMES Bowdoin's role in the American Revolution has never re- ceived frofer fublic recognition. Bowdoin^s friendship with Franklin, Washington, Revere and others fut him in the midst of the struggle for Independence; at the same time his social position and family ties gave him entree to British leaders and officials. In lyyo, his own brother-in-law was Colonial Secretary for the Gover- nor, yet Bowdoin wrote the tract on the Boston Massacre, which clearly blamed the British for the incident and sent Boston down the road toward Revolution. This exhibition seeks not only to reveal Bowdoin^s importance in the Revolution, but also his contributions in the field of finance, science, literature and the arts. He was as well educated as any American in the eighteenth century and subscribed to the principles of The Enlightenment, which encouraged iyivestigation into the nat- ural world and practice of the graces of life. To accomplish these goals, the Museum commissioned the frst major biography of Bowdoin in the form of a catalogue which will be published on July 4, igy6. We are most grateful to Professor Gordon E. Kershaw, author of The Kennebeck Proprietors, 1749- 1775, and specialist on James Bowdoin, for writing the catalogue. The Museum has also attempted to tell the Bowdoin story purely with objects of art. Like books, objects contain data and ideas. Their stories can be ^Wead^^ if only one examines the object and asks certain questions such as: what kind of society is needed to produce such a work? What traditional or European motifs are used, which motifs are rejected and what new ones are introduced? What was the use or function of the object? Beyond this, the exhibition is intended to show that James Bowdoin expressed an interest in art not only in commissions for painting and silver but also in the execution of a bank note or scientific instrument. -

Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820

128 American Antiquarian Society. [April, BIBLIOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN NEWSPAPERS, 1690-1820 PART III ' MARYLAND TO MASSACHUSETTS (BOSTON) COMPILED BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM The following bibliography attempts, first, to present a historical sketch of every newspaper printed in the United States from 1690 to 1820; secondly, to locate all files found in the various libraries of the country; and thirdly, to give a complete check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society. The historical sketch of each paper gives the title, the date of establishment, the name of the editor or publisher, the fre- quency of issue and the date of discontinuance. It also attempts to give the exact date of issue when a change in title or name of publisher or frequency of publication occurs. In locating the files to be found in various libraries, no at- tempt is made to list every issue. In the case of common news- papers which are to be found in many libraries, only the longer files are noted, with a description of their completeness. Rare newspapers, which are known by only a few scattered issues, are minutely listed. The check list of the issues in the library of the American Antiquarian Society follows the style of the Library of Con- gress "Check List of Eighteenth Century Newspapers," and records all supplements, missing issues and mutilations. The arrangement is alphabetical by states and towns. Towns are placed according to their present State location. For convenience of alphabetization, the initial "The" in the titles of papers is disregarded. Papers are considered to be of folio size, unless otherwise stated. -

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1 SARA B. CHASE* ven before they built their first governmental bodies. The Royal Governor structure to house a merchants ’ ex- and his Council met in a chamber at the east E change and government meeting end of the second floor, while the General hall, the early settlers of Boston had Assembly of the Province, with representa- selected a site near Long Wharf for a tives from each town, met in a larger marketplace. Early in 1658 they built there chamber in the middle of the second floor. a medieval half-timbered Town House. At the west end of the second floor was a That building, the first Boston Town smaller chamber where both the superior House, burned to the ground in October, and the inferior courts of Suffolk County 1711. It was replaced by a brick building, held sessions. Until 1742 when they moved erected on the same site. This building, like to Faneuil Hall, Bostons’ Selectmen met in the earlier Town House, had a “merchants’ the middle (or representatives)’ chamber walk” on the first floor and meeting cham- and used a few finished rooms on the third bers for the various colonial government floor for committee meetings. bodies on the second floor. The first floor served primarily as a mer- Although this new building was called by chants ’ exchange, as it had in the previous various names--the Court House, the Town House. Situated less than one- Second Town House, the Province House quarter mile from Long Wharf, the Old (not to be confused with the Peter Sergeant State House was a convenient first stop for House which was also called by that name) ships ’ captains when they landed in Bos- --the name most frequently used in refer- ton. -

Financial District.04

t Christopher Clinton St Columbus C t o S Waterfront t th n or w membershipapplication S g N Park t r e e rf s ha s g W s r Lon C e e 2 a M h I would like to: 0 v t m S am a 0 o e h A at 2 h t C R r h Government n S n c join renew be on email list o a o i l l h Aquarium A t w m Center s ܙ ܙ ܙ k R C a C o ornhil A t l l n S n t B k o e a I r 4 k a t C n n l w n o r s t u d e a corporate levels [benefits on back] t r t t F r i n W i r t S c S a t 6 y a al B tr t n © S A e e l C t S 5 racewalker $5000 State Sta K START v i 3 t ܙ l e b t t e k S y Mil o r strider $2500 e v t F S u r 7 ܙ A END C 2 S al o a l 1 r t t e l o n C u t e stroller $1000 e a n C q S s g m Q ܙ H t t S r n S a S e y u 8 ambler $300 t o Pl n i s t a by k e e il t l l s g K t i I ܙ 20 C g r k n t n i ha S m d y M P e c n r P S x S ia i h E e o t i t t r t o A S s t a l h e n l s t L W a individual/family levels [benefits on back] s n P t u s di e o S W t In a s B u as a o e e E i aw ro C o ll m 19 v H a S W d n c e e H t sustaining $500—$5000 S t r B t T t l D Water o ܙ a w c S P tte Ro 9 i supporter $100—$499 t 17 ry S - n n Sc 18 m r ܙ o a ho St ol a t m B m t St O n o r friend $65 e p S ing l c s r s Spr iv h w - a n i ܙ a T e e o h c La r to S t i rt P n S S D dual/family $50 h C in ro e t l S v v t t J y l ܙ n t in 16 a e o S d l B r ce k W n $30 o r C il e individual o P t t W a t m Milk S M ܙ f i ie C s 15 P ld St c o t h H S t e S Hig n o a a t n S F 10 n additional contribution $___________ D m g r in e l l i y r l a e k B t S o d le e n n v t a e s r n P o F w s F l r e i r a n a name a o s l n H F h ic l k h S t s l i t r P i 11 t n H O s u e ll a organization w ’ M a le S li S v d H y t e Pl n W t r n in S s address ter St t o a St Downtown 13 12 t s n e Crossing S o P no o o l t w P S B t P e S y l 14 a s u e r day phone m l B l w u G S | o m s B a s r t e H e t id B r y S t l eve. -

Building Order on Beacon Hill, 1790-1850

BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Spring 2016 © 2016 Jeffrey Eugene Klee All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 10157856 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10157856 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

A General History of the Burr Family, 1902

historyAoftheBurrfamily general Todd BurrCharles A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE BURR FAMILY WITH A GENEALOGICAL RECORD FROM 1193 TO 1902 BY CHARLES BURR TODD AUTHOB OF "LIFE AND LETTERS OF JOBL BARLOW," " STORY OF THB CITY OF NEW YORK," "STORY OF WASHINGTON,'' ETC. "tyc mis deserves to be remembered by posterity, vebo treasures up and preserves tbe bistort of bis ancestors."— Edmund Burkb. FOURTH EDITION PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR BY <f(jt Jtnuhtrboclur $«88 NEW YORK 1902 COPYRIGHT, 1878 BY CHARLES BURR TODD COPYRIGHT, 190a »Y CHARLES BURR TODD JUN 19 1941 89. / - CONTENTS Preface . ...... Preface to the Fourth Edition The Name . ...... Introduction ...... The Burres of England ..... The Author's Researches in England . PART I HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL Jehue Burr ....... Jehue Burr, Jr. ...... Major John Burr ...... Judge Peter Burr ...... Col. John Burr ...... Col. Andrew Burr ...... Rev. Aaron Burr ...... Thaddeus Burr ...... Col. Aaron Burr ...... Theodosia Burr Alston ..... PART II GENEALOGY Fairfield Branch . ..... The Gould Family ...... Hartford Branch ...... Dorchester Branch ..... New Jersey Branch ..... Appendices ....... Index ........ iii PART I. HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL PREFACE. HERE are people in our time who treat the inquiries of the genealogist with indifference, and even with contempt. His researches seem to them a waste of time and energy. Interest in ancestors, love of family and kindred, those subtle questions of race, origin, even of life itself, which they involve, are quite beyond their com prehension. They live only in the present, care nothing for the past and little for the future; for " he who cares not whence he cometh, cares not whither he goeth." When such persons are approached with questions of ancestry, they retire to their stronghold of apathy; and the querist learns, without diffi culty, that whether their ancestors were vile or illustrious, virtuous or vicious, or whether, indeed, they ever had any, is to them a matter of supreme indifference. -

Conference Program

Special ThankS for Your SupporT: Conference Chairs Scholarship Committee Treasurer Susan Leidy, Deputy Director, Currier Maria Cabrera, MA Scott Stevens, Executive Director Museum of Art Trudie Lamb Richmond, CT Museums of Old York Wendy Lull, President, Seacoast Science Secretary Center Conference Sponsors Pieter Roos, Executive Director Michelle Stahl, Executive Director, Directors and Trustees Dinner Newport Restoration Foundation Peterborough Historical Society Museum Search & Reference Opening Lunch Dessert Sponsor PAG Representatives Conference Program Selection Tru Vue, Inc Elaine Clements, Director Andover Historical Society Committee Newcomers Reception Kay Simpson, MA, Chair Tufts University Museum Studies Program Emmie Donadio, Chief Curator Maureen Ahern, NH Middlebury College Museum of Art Jennifer Dubé-Works, ME Welcome and Wake-up Coffee Sponsor Julie Edwards, VT Opportunity Resources, Inc. Ron Potvin, Assistant Director and Curator Emily Robertson, MA Supporting Sponsors John Nicholas Brown Center Douglas Stark, RI Andrew Penziner Productions LLC Kay Simpson, Director of Education and Anne von Stuelpnagel, CT Cherry Valley Group Institutional Advancement CultureCount Springfield Museums Local Committee Scholarship Sponsors At-large Representatives David Blackburn Gaylord Bros., Inc. Neil Gordon, CEO Gina Bowler John Nicholas Brown Center The Discovery Museums, MA Mal Cameron Laura B. Roberts Linda Carpenter University Products Diane Kopec, Independent Museum Professional James Coleman Connie Colom NEMA Staff Michelle Stahl, Executive Director Peterborough Historical Society Lisa Couturier Jane Coughlin Michael Creasey BJ Larson State Representatives Aurore Eaton Heather A. Riggs Connecticut Margaret Garneau Katheryn P. Viens Trudie Lamb Richmond, Director of Public Jeanne Gerulskis Programs A special thank you to Beverly Joyce, President Tom Haynes Mashantucket Pequot Museum Douglas Heuser of Design Solutions for her design of this year’s Beth McCarthy conference logo. -

Freedom Trail N W E S

Welcome to Boston’s Freedom Trail N W E S Each number on the map is associated with a stop along the Freedom Trail. Read the summary with each number for a brief history of the landmark. 15 Bunker Hill Charlestown Cambridge 16 Musuem of Science Leonard P Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Boston Harbor Charlestown Bridge Hatch Shell 14 TD Banknorth Garden/North Station 13 North End 12 Government Center Beacon Hill City Hall Cheers 2 4 5 11 3 6 Frog Pond 7 10 Rowes Wharf 9 1 Fanueil Hall 8 New England Downtown Crossing Aquarium 1. BOSTON COMMON - bound by Tremont, Beacon, Charles and Boylston Streets Initially used for grazing cattle, today the Common is a public park used for recreation, relaxing and public events. 2. STATE HOUSE - Corner of Beacon and Park Streets Adjacent to Boston Common, the Massachusetts State House is the seat of state government. Built between 1795 and 1798, the dome was originally constructed of wood shingles, and later replaced with a copper coating. Today, the dome gleams in the sun, thanks to a covering of 23-karat gold leaf. 3. PARK STREET CHURCH - One Park Street, Boston MA 02108 church has been active in many social issues of the day, including anti-slavery and, more recently, gay marriage. 4. GRANARY BURIAL GROUND - Park Street, next to Park Street Church Paul Revere, John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and the victims of the Boston Massacre. 5. KINGS CHAPEL - 58 Tremont St., Boston MA, corner of Tremont and School Streets ground is the oldest in Boston, and includes the tomb of John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.