Building Order on Beacon Hill, 1790-1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rebecca J. Bertrand All Rights Reserved MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand Approved: __________________________________________________________ Brock Jobe, M.A. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Every Massachusetts schoolchild walks Boston’s Freedom Trail and learns the story of the Hancock house. Its demolition served as a rallying cry for early preservationists and students of historic preservation study its importance. Having been both a Massachusetts schoolchild and student of historic preservation, this project has inspired and challenged me for the past nine months. To begin, I must thank those who came before me who studied the objects and legacy of the Hancock house. I am greatly indebted to the research efforts of Henry Ayling Phillips (1852- 1926) and Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1856-1951). Their research notes, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts served as the launching point for this project. This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of my thesis adviser, Brock Jobe. -

Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice in Boston, 1900 to 2000

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-22-2019 "The Dream is in the Process:" Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice in Boston, 1900 to 2000 Michael J. Brennan University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Brennan, Michael J., ""The Dream is in the Process:" Environmental Racism and Environmental Justice in Boston, 1900 to 2000" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3102. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3102 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE DREAM IS IN THE PROCESS:” ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN BOSTON, 1900 TO 2000 By Michael J. Brennan B.S. University of Maine at Farmington, 2001 A.L.M. Harvard University Extension School, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American History) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2019 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor Emeritus of History Elizabeth McKillen, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Liam Riordan, Professor of History Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History and Graduate Coordinator of History Program Roger J.H. King, Associate Professor of Philosophy THE DREAM IS IN THE PROCESS: ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE IN BOSTON, 1900 TO 2000 By: Michael J. Brennan Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Richard Judd An Abstract of the Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in American History (August 2019) The following work explores the evolution of a resident-directed environmental activism that challenged negative public perception to redevelop their community. -

City of Gloucester Community Preservation Committee

CITY OF GLOUCESTER COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE BUDGET FORM Project Name: Masonry and Palladian Window Preservation at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Applicant: Historic New England SOURCES OF FUNDING Source Amount Community Preservation Act Fund $10,000 (List other sources of funding) Private donations $4,000 Historic New England Contribution $4,000 Total Project Funding $18,000 PROJECT EXPENSES* Expense Amount Please indicate which expenses will be funded by CPA Funds: Masonry Preservation $13,000 CPA and Private donations Window Preservation $2,200 Historic New England Project Subtotal $15,200 Contingency @10% $1,520 Private donations and Historic New England Project Management $1,280 Historic New England Total Project Expenses $18,000 *Expenses Note: Masonry figure is based on a quote provided by a professional masonry company. Window figure is based on previous window preservation work done at Beauport by Historic New England’s Carpentry Crew. Historic New England Beauport, The Sleeper-McCann House CPA Narrative, Page 1 Masonry Wall and Palladian Window Repair Historic New England respectfully requests a $10,000 grant from the City of Gloucester Community Preservation Act to aid with an $18,000 project to conserve a portion of a masonry wall and a Palladian window at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a National Historic Landmark. Project Narrative Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, was the summer home of one of America’s first professional interior designers, Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934). Sleeper began constructing Beauport in 1907 and expanded it repeatedly over the next twenty-seven years, working with Gloucester architect Halfdan M. -

FORM a - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet

Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area FORM A - AREA See Data Wilmington TEW.A, See Data Sheet E Sheet MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION MASSACHUSETTS ARCHIVES BUILDING 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Town/City: Tewksbury Photograph Place (neighborhood or village): Tewksbury Centre Name of Area: Tewksbury Centre Area Present Use: Mixed use Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1737–2016 Overall Condition: Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: Vinyl siding and windows, spot demolition leaving vacant lots, late 20th c. Acreage: 57.5ac Photo 1. 60 East Street, looking northwest. Recorded by: V. Adams, G. Pineo, J. Chin, E. Totten, PAL Organization: Tewksbury Historical Commission Date (month/year): March 2020 Locus Map ☐ see continuation sheet 4/11 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET TEWKSBURY TEWKSBURY CENTRE AREA MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 TEW.A, E See Data Sheet ☒ Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Tewksbury Centre Area (TEW.A), the civic and geographic heart of Tewksbury, encompasses approximately 58 buildings across 57.5 acres centered on the Tewksbury Common at the intersection of East, Pleasant, and Main streets and Town Hall Avenue. Tewksbury Centre has a concentration of civic, institutional, commercial, and residential buildings from as early as ca. 1737 through the late twentieth century; mid-twentieth-century construction is generally along smaller side streets on the outskirts of the Tewksbury Centre Area. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1 SARA B. CHASE* ven before they built their first governmental bodies. The Royal Governor structure to house a merchants ’ ex- and his Council met in a chamber at the east E change and government meeting end of the second floor, while the General hall, the early settlers of Boston had Assembly of the Province, with representa- selected a site near Long Wharf for a tives from each town, met in a larger marketplace. Early in 1658 they built there chamber in the middle of the second floor. a medieval half-timbered Town House. At the west end of the second floor was a That building, the first Boston Town smaller chamber where both the superior House, burned to the ground in October, and the inferior courts of Suffolk County 1711. It was replaced by a brick building, held sessions. Until 1742 when they moved erected on the same site. This building, like to Faneuil Hall, Bostons’ Selectmen met in the earlier Town House, had a “merchants’ the middle (or representatives)’ chamber walk” on the first floor and meeting cham- and used a few finished rooms on the third bers for the various colonial government floor for committee meetings. bodies on the second floor. The first floor served primarily as a mer- Although this new building was called by chants ’ exchange, as it had in the previous various names--the Court House, the Town House. Situated less than one- Second Town House, the Province House quarter mile from Long Wharf, the Old (not to be confused with the Peter Sergeant State House was a convenient first stop for House which was also called by that name) ships ’ captains when they landed in Bos- --the name most frequently used in refer- ton. -

Gentrification of Codman Square Neighborhood: Fact Or Fiction?

fi ti n of Codman Square Neighborhood: Fact or Fiction? Gentri ca o Challenges and Opportunities for Residential and Economic Diversity of a Boston Neighborhood A Study of Neighborhood Transformation and Potential Impact on Residential Stability A A Publication of Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation 587 Washington Street Dorchester Boston MA 02124 Executive Director: Gail Latimore Gentrification Blues I woke up this morning, I looked next door — There was one family living where there once were four. I got the gentrifi-, gentrification blues. I wonder where my neighbors went ‘cause I Know I’ll soon be moving there too. Verse from the song ‘Gentrification Blues’ by Judith Levine and Laura Liben, Broadside (Magazine), August, 1985, issue #165 Report Credits: Principal Researcher and Consultant: Eswaran Selvarajah (Including graphics & images) Contributor: Vidhee Garg, Program Manager, CSNDC (Sec. 6 - HMDA Analysis & Sec. 7 - Interviews with the displaced) Published on: July 31, 2014 Contact Information Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation 587 Washington Street Dorchester MA 02124 Telephone: 617 825 4224 FAX: 617 825 0893 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: http://www.csndc.com Executive Director: Gail Latimore [email protected] Gentrification of Codman Square: Fact or Fiction? Challenges and Opportunities for Residential and Economic Diversity of a Boston Neighborhood A Study of Neighborhood Transformation and Potential Impact on Residential Stability A Publication of Codman Square Neighborhood Development Corporation 587 Washington Street Dorchester Boston MA 02124 Executive Director: Gail Latimore Codman Square, Dorchester ii CONTENTS Abbreviations Acknowledgments Executive Summary Introduction 1 1. Context: Studying Neighborhood Change and Housing Displacement 4 2. Gentrification: Regional and Local Factors Behind the Phenomenon 8 3. -

Creating an American Identity

Creating an American Identity 9780230605268ts01.indd i 4/24/2008 12:26:30 PM This page intentionally left blank Creating an American Identity New England, 1789–1825 Stephanie Kermes 9780230605268ts01.indd iii 4/24/2008 12:26:30 PM CREATING AN AMERICAN IDENTITY Copyright © Stephanie Kermes, 2008. All rights reserved. First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978–0–230–60526–8 ISBN-10: 0–230–60526–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kermes, Stephanie. Creating an American identity : New England, 1789–1825 / Stephanie Kermes. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–230–60526–5 1. New England—Civilization—18th century. 2. New England— Civilization—19th century. 3. Regionalism—New England—History. 4. Nationalism—New England—History. 5. Nationalism—United States—History. 6. National characteristics, American—History. 7. Popular culture—New England—History. 8. Political culture—New England—History. 9. New England—Relations—Europe. 10. Europe— Relations—New England. I. Title. F8.K47 2008 974Ј.03—dc22 2007048026 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: July 2008 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America. -

House Research Bibliography

HOUSE RESEARCH LISTING, comp. by James P. LaLone, rev. Aug., 2016. “A FARM BY ANY OTHER NAME…”, by David A. Norris, in INTERNET GENEALOGY, Oct/Nov 2010, pp.13-15 ABBEYS, CASTLES AND ANCIENT HALLS OF ENGLAND & WALES: THEIR LEGENDARY LORE & POPULAR HISTORY, by John Timbs & Alexander Gunn, 3 vls. ABRAMS GUIDE TO AMERICAN HOUSE STYLES, by William Morgan. “AGAINST THE TIDE: FRENCH CANADIAN BARN BUILDING TRADITIONS IN THE ST. JOHN VALLEY OF MAINE”, by Victor A. Konrad,, in THE AMERICAN REVIEW OF CANADIAN STUDIES, v.12, #2, Summer 1982, pp.22-36. THE AMBROISE TREMBLE FARM: KENSINGTON ROAD, (MI), by Bruce L. Sanders THE AMERICAN BUNGALOW, 1880-1930, by Clay Lancaster AMERICAN ESTATES AND GARDENS, by Barr Ferree AMERICAN HOUSES IN HISTORY, by Arnold Nicholson AMERICA'S HISTORIC HOUSES AND RESTORATIONS., by Ivan Haas AMERICA'S HISTORIC HOUSES; THE LIVING PAST, by Robert L. Polley AN ACCOMPT OF THE MOST CONSIDERABLE ESTATES AND FAMILIES IN THE COUNTY OF CUMBERLAND … (ENG.), by John Denton ANCIENT CATHOLIC HOMES OF SCOTLAND, by Odo Blundell ARCHAEOLOGY OF BUILDINGS, by Richard K. Morriss ARCHITECTURE AND TOWN PLANNING IN COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA, by James D. & Georgiana W. Kornwolf ARCHITECTURE IN EARLY NEW ENGLAND, by Abbott Lowell Cummings THE ARCHITECTURE OF COUNTRY HOUSES, by A. J. Downing. New introd. by George B. Tatum. ARCHITECTURE STYLES SPOTTER’S GUIDE: CLASSICAL TEMPLES TO SOARING SKYSCRAPERS, by Sarah Cunliffe & Jean Loussier, eds. ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN CANADA: A BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE TO THE LITERATURE, by Loren R. Lerner & Mary F. Williamson -

Applying Concepts from Historical Archaeology to New England's Nineteenth-Century Cookbooks Anne Yentsch

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 42 Foodways on the Menu: Understanding the Lives of Households and Communities through the Article 8 Interpretation of Meals and Food-Related Practices 2013 Applying Concepts from Historical Archaeology to New England's Nineteenth-Century Cookbooks Anne Yentsch Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Yentsch, Anne (2013) "Applying Concepts from Historical Archaeology to New England's Nineteenth-Century Cookbooks," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 42 42, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol42/iss1/8 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol42/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 42, 2013 111 Applying Concepts from Historical Archaeology to New England’s Nineteenth-Century Cookbooks Anne Yentsch This article describes a study of New England cookbooks as a data source for historical archaeologists. The database for this research consisted of single-authored, first-edition cookbooks written by New England women between 1800 and 1900, together with a small set of community cookbooks and newspaper advertisements. The study was based on the belief that recipes are equivalent to artifact assemblages and can be analyzed using the archaeological methods of seriation, presence/absence, and chaîne opératoire. The goal was to see whether change through time could be traced within a region, and why change occurred; whether it was an archetypal shift in food practice, modifications made by only a few families, change that revolved around elite consumption patterns, or transformations related to gender and other social forces unrelated to market price. -

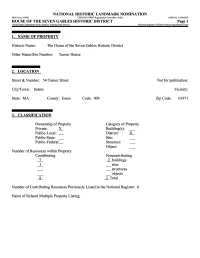

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: The House of the Seven Gables Historic District Other Name/Site Number: Turner House 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 54 Turner Street Not for publication: City/Town: Salem Vicinity: State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01971 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: 2L_ Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal:_ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 7 2 buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 8 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria.