Copyright by Naoko Kato 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanghai, China's Capital of Modernity

SHANGHAI, CHINA’S CAPITAL OF MODERNITY: THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE AND URBAN EXPERIENCE OF WORLD EXPO 2010 by GARY PUI FUNG WONG A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY School of Government and Society Department of Political Science and International Studies The University of Birmingham February 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines Shanghai’s urbanisation by applying Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space and everyday life. A review of Lefebvre’s theories indicates that each mode of production produces its own space. Capitalism is perpetuated by producing new space and commodifying everyday life. Applying Lefebvre’s regressive-progressive method as a methodological framework, this thesis periodises Shanghai’s history to the ‘semi-feudal, semi-colonial era’, ‘socialist reform era’ and ‘post-socialist reform era’. The Shanghai World Exposition 2010 was chosen as a case study to exemplify how urbanisation shaped urban experience. Empirical data was collected through semi-structured interviews. This thesis argues that Shanghai developed a ‘state-led/-participation mode of production’. -

How China Started the Second Sino-Japanese War: Why Should Japan Apologize to China?

How China Started the Second Sino-Japanese War: Why Should Japan Apologize to China? By Moteki Hiromichi Society for the Dissemination of Historical Facts © 1 Introduction In the so-called "apology issue," which concerns Japan's conduct in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War, there exists two opposing points of view: "I guess the only thing we can do is to keep on apologizing until China tells us, 'The problems between us may not be settled, but for now you have sufficiently apologized.'" -Murakami Haruki1 "A grateful China should also pay respect to Yasukuni Shrine." -Ko Bunyu2 Mr. Murakami's opinion is based on the belief that Japan waged an aggressive war against China, a belief shared by many Japanese even if they don't know the reason why. This belief holds that the Japanese should be completely repentant over that act of aggression for the sake of clearing our own conscience. There are two major problems with this point of view. First of all, it rests on the conventional wisdom that Japan was guilty of aggression towards China. Many people will perhaps respond to that by saying something like, "What are you talking about? The Japanese Army invaded continental China and waged war there. Surely that constitutes a war of aggression." However, let's imagine the following scenario. What if the Japan Self-Defense Forces launched an unprovoked attack on American military units, which are stationed in Japan in accordance with the provisions of the US-Japan Security Treaty, and a war broke out on Japanese territory? Because the fighting would be taking place in Japan, does that mean that, in this scenario, the US Army is undeniably the aggressor? No matter how distasteful a person might find the US military presence to be, under international law, Japan would be deemed the aggressor here. -

The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in U.S.- Japan-China Relations サンフランシスコ体制 米日中関係の過去、 現在、そして未来

Volume 12 | Issue 8 | Number 2 | Article ID 4079 | Feb 23, 2014 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in U.S.- Japan-China Relations サンフランシスコ体制 米日中関係の過去、 現在、そして未来 John W. Dower controversies and tensions involving Japan, China, and the United States. NOTE: This essay, written in January 2013, appears as the first section in a book co- Take, for example, a single day in China: authored by John W. Dower and GavanSeptember 18, 2012. Demonstrators in scores McCormack and published in Japaneseof Chinese cities were protesting Japan's claims translation by NHK Shuppan Shinsho in to the tiny, uninhabited islands in the East January 2014 under the title Tenkanki no Nihon China Sea known as Senkaku in Japanese and e: "Pakkusu Amerikana" ka-"Pakkusu Ajia" ka Diaoyu in Chinese-desecrating the Hi no Maru ("Japan at a Turning Point-Pax Americana? Pax flag and forcing many China-based Japanese Asia?"; the second section is an essay by factories and businesses to temporarily shut McCormack on Japan's client-state relationship down. with the United States focusing on the East China Sea "periphery," and the book concludes Simultaneously, Chinese leaders were accusing with an exchange of views on current tensions the United States and Japan of jointly pursuing in East Asia as seen in historical perspective). a new "containment of China" policy- An abbreviated version of the Dower essay also manifested, most recently, in the decision to will be included in a forthcoming volume on the build a new level of ballistic-missile defenses in San Francisco System and its legacies edited Japan as part of the Obama administration's by Kimie Hara and published by Routledge. -

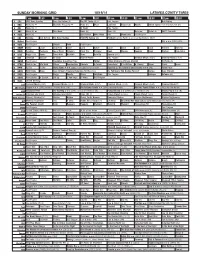

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray. Dancer who was introduced to reality TV audiences as a competitor on Lifetime's Dance Moms. She became the star of the Lifetime series Raising Asia. She played Sydney Simpson on American Crime Story in 2016. Before Fame. She started dancing at age 2. She trained in figure skating and dance while growing up. Trivia. She has placed first on the Dance Moms episodes "Rock That," "Ready for War," and "The Robot." She played Jasmine in two episodes of Grey's Anatomy in 2016. She sang the national anthem at a Los Angeles Clippers game at the Staples Center. She performed on tour with Mariah Carey. Family Life. She has a younger sister named Bella Blu. Her parents are named Kristie Ray and Shawn Ray. Green Print. Edited As digital technology became integral to the capitalist market dystopia of the first decades of the 21st century, it refashioned both our ways of working and our ways of consuming, as well as. Green Print. About. Merlin Press has been publishing books for over 30 years. We cover wide variety of subjects and categories with our main focus being on social & political titles covering key issues that concern all of us. For further information visit the representation page, or contact our team. Contact. Contact: Customer Services. Merlin Press, Central Books Building 50 Freshwater Rd Chadwell Heath London RM8 1RX. Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland. Automatic capture for your stadium has arrived. Hudl Focus Outdoor records, uploads and livestreams American football and soccer games. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science the Crafting Of

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Crafting of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, 1945-1951 Seung Mo Kang A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2020 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,908 words. 2 Acknowledgements I really could not have done this project alone and I owe thanks to so many people. I would first like to thank my supervisor Dr. Antony Best for always being willing to talk to me and for his meticulous review of my work. Throughout the course of my studies, he has taught me how to prioritize, summarize, clarify and most importantly to engage and write like an historian and not simply copy-and-paste interesting facts that previous books and articles did not mention. -

Your Name Here

PHENOMENAL BODIES, PHENOMENAL GIRLS: HOW YOUNG ADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPERIENCE BEING ENOUGH IN THEIR BODIES by HILARY ELIZABETH HUGHES (Under the Direction of Mark D. Vagle) ABSTRACT Drawing on philosophers (Ahmed, 2006; Fanon, 1986; Heidegger, 1927, 1962, 1992; Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and social science scholars (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008; Vagle, 2009, 2010, 2011; van Manen, 1990, 2000) for this phenomenological study, I asked what it was like for the seventh grade girls who participated with me in a year-long writing group to experience moments where they found themselves in bodily-not-enoughness: moments when someone or something was telling them they were not enough of something in their bodies. Using a multigenre magazine format for the dissertation, I describe how I learned—as an adult, a qualitative researcher, a middle grades teacher, and a teacher educator—from these seventh grade girls how to be-enough in my own body, by illustrating various moments when some of the girls seemed to talk-back-TO those societal messages telling them they were not pretty- enough, thin-enough, English-speaking-enough, white-enough, popular-enough, or smart-enough by embodying some kind of resistance-to those messages. I then suggest that if we as adults, qualitative researchers, middle grades educators, and teacher educators wish to try and understand better how female young adolescents of color experience living in their bodies, we should begin listening differently so that we can begin seeing/knowing/thinking the bodies of young adolescents, -

Csr Report 2017

Towards the Realization of a Resource-Recycling Society CSR REPORT 2017 * This report uses forest-certified paper and eco-friendly soy ink. Contents Highly efficient recovery of multi-elements 1 DOWA’s CSR Supply of conflict mineral-free gold and tin 3 Special Feature: The Advancement of DOWA 9 Top Message Proper treatment and prevention of pollution 11 About the DOWA Group Reduction of waste volume Metal Heat recovery and power generation products 15 CSR Policy and Plan Resource Recycling at the DOWA Group 17 CSR Initiatives by Sector Governance Society 23 Safety 27 Environment Manufacturing 35 Society 45 Editorial Policy and Target Organizations of the Report Market research and analysis Stable recovery 46 Opinion of a Third Party Research and new technology development Raw material analysis and evaluation Landfill Rare metals plant Environmental conservation measures Incineration plant Recycling smelter Zinc smelter Sales Stable supply of base metals Sales and Improvement logistics of recovery Securing the stability Laboratory of rare metals Utilization Analytical center External partners Precious metal Joint research and recycling plant Environment technical cooperation consulting Supply chain management Recycled material manufacturing plant Home appliance recycling factory Reuse usage Shredder dust processing plant Automobile Recycling rate recycling plant Recycled improvement Recycled item raw expansion materials DOWA’s CSR Reduction of waste Corporate Philosophy Energy Water Ore Through its business operations on the world stage, Natural Minimizing the environmental resources burden of resource development Dowa seeks to contribute to the creation of Saving energy, circulating water prosperous communities and the emergence of a and minimizing input resource recycling society. DOWA’s Business and SDGs Based on this corporate philosophy, we work on solving various social The responsibility of making. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 282 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. OUR READERS Dai Min Many thanks to the travellers who used the Massive thanks to Dai Lu, Li Jianjun and Cheng Yuan last edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, for all their help and support while in Shanghai, your useful advice and interesting anecdotes: Thomas assistance was invaluable. Gratitude also to Wang Chabrieres, Diana Cioffi, Matti Laitinen, Stine Schou Ying and Ju Weihong for helping out big time and a Lassen, Cristina Marsico, Rachel Roth, Tom Wagener huge thank you to my husband for everything. -

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District

China International Import Expo Presentation of Investment Promotion Activities in Hongkou District Shanghai Hongkou District Comm ission of Commerce (Economy) October 1 0, 2018 SHANGHAI HONGKOU Hongkou district is one of the earliest open areas in China, with a deep cultural background and excellent geographical location. On the south side of Hongkou district lies the Huangpu River and the Wusong River. The North Bund of Hongkou district, the old Bund of Huangpu district and the Lujiazui of Pudong New Area form a golden triangle, separated by the Huangpu River. Hongkou district has a total area of 23.48 k㎡, with a resident population of 800,000. 虹 口 上 海 23.4 k㎡ 6340 k㎡ 中 国 9,634,057 k㎡ SHANGHAI HONGKOU Development Planning of Hongkou District Target for 2020 The Northern Science and Technology Innovation Industry Gathering Area mainly includes the Dabaishu Science and Technology Innovation Center, 1.Establish the Shanghai international Fu Dan-Caida Innovation Area, Tongji Innovation Area, etc. We will focus financial center and international shipping on the renewal and utilization of stock plots, industrial plants and industrial parks. center as import ant functional area 2. Establish an influential creative The Central Commercial and Tourist Sports Development Area is mainly including the area of Hongkou football field area, Sichuan entrepreneurial zone North Road Park-Music Valley, and the area of Ruihong Tiandi. The 3. Establish an accessible and diversified key projects include Financial Street Hailun Center etc. Shanghai cultural heritage development zone. Double Loading Area for Financial and Shipping 4. Establish a high quality urban areas that Industry in the North Bund includes the North Bund are suitable for living, working and Business and Cultural District, Zhoushan Road Historical Creative Block ect. -

Meiji University Application Guidelines for Fall Admission for International Undergraduate Programs (TRANSFER) -English Track 2013

Meiji University Application Guidelines for Fall Admission for International Undergraduate Programs (TRANSFER) -English Track 2013- Meiji University School of Global Japanese Studies Address : 1-9-1 Eifuku, Suginami-ku, Tokyo, JAPAN 168-8555 Telephone : +81-3-5300-1519 Fax : +81-3-5300-1549 URL : http://www.meiji.ac.jp/nippon/ english/englishtrack/ *School of Global Japanese Studies is scheduled to move to Nakano Campus in April, 2013. New contact information after April, 2013 will be out on website. 【 Contents 】 1. Before Applying ··························································· 1 2. Application Eligibility ··················································· 1 3. Admission Schedule and Procedure ··········································· 2 4. Application Procedure ····················································· 2 5. Screening Fee and Payment Procedure ········································ 5 6. Application Documents ····················································· 7 7. Announcement of Admission Decision ········································· 16 8. Admission Procedure ························································ 16 9. Visa ······································································· 17 10. Additional Information ···················································· 19 11. Tuition and Fees for 2013 ·················································· 20 【Access】 ····································································· 21 【Inquiries about application documents】 International Student -

The 15 Macroeconomics Conference

The 15th Macroeconomics Conference December 14 (Sat.) and 15 (Sun.), 2013 Venue: Kojima Hall 2nd Floor, Conference Room Hongo Campus, University of Tokyo http://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/about/documents/Hongo_CampusMap_E.pdf Organizers (Representatives) Tsutomu Watanabe (University of Tokyo) Yoshiyasu Ono (Osaka University) Naohito Abe (Hitotsubashi University) Program Committee Kosuke Aoki (University of Tokyo) Kazuo Ogawa (Osaka University) Etsuro Shioji (Hitotsubashi University) Main Sponsor UTokyo Price Project Co-sponsors Grant for Prominent Graduate Schools under the Program "Human Behavior and Socioeconomic Dynamics", Graduate School of Economics and Institute of Social and Economic Research, Osaka University Research Center for Price Dynamics, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University Tokyo Center for Economic Research (TCER) Session format: paper presentation (20 minutes), discussant’s comments (20 minutes) and general discussion (20 minutes) Language: Unless otherwise noted, paper presenters and discussants have agreed to switch to English if at least one person in the audience is a non-Japanese speaker. 1 Program Saturday, December 14 (Please note: no lunch will be served!) 12:30 Registration Session 1: Financing and Macroeconomics Chair: Kosuke Aoki (University of Tokyo) 13:00-14:00 Ryo Jinnai (Texas A&M) “Liquidity, Trends and the Great Recession” (with Pablo A. Guerron-Quintana) Slides Discussant: Yasuo Hirose (Keio University) Slides 14:00-15:00 Takushi Kurozumi (Bank of Japan) “What Caused Japan’s Great Stagnation