Your Name Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Ashley N. Mack 2013

Copyright by Ashley N. Mack 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Ashley N. Mack Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: DISCIPLINING MOMMY: RHETORICS OF REPRODUCTION IN CONTEMPORARY MATERNITY CULTURE Committee: Dana L. Cloud, Supervisor Joshua Gunn Barry Brummett Sharon J. Hardesty Christine Williams DISCIPLINING MOMMY: RHETORICS OF REPRODUCTION IN CONTEMPORARY MATERNITY CULTURE by Ashley N. Mack, B.A.; B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2013 Dedication To Tiffany—for being an awesome lady, thinker, worker, “true” sister, daughter, and mother. Acknowledgements My family has something of a “curse”: Multiple generations of women have been single, working mothers. Therefore, the social pressures, expectations and norms of motherhood have always permeated my experiences of reproduction and labor. Everything I do has been built on the backs of the women in my family—so it is important that I thank them first and foremost. I would be remised if I did not also specifically thank my big sister, Tiffany, for sharing her experiences as a mother with me. Hearing her stories inspired me to look closer at rhetorics of maternity and this project would not exist if she were not brave enough to speak up about issues that produce shame and fear for many moms. Dana Cloud, my advisor, is a shining light at the end of the many dark tunnels that academic work can produce. -

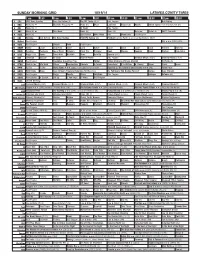

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland Asia Ray. Dancer who was introduced to reality TV audiences as a competitor on Lifetime's Dance Moms. She became the star of the Lifetime series Raising Asia. She played Sydney Simpson on American Crime Story in 2016. Before Fame. She started dancing at age 2. She trained in figure skating and dance while growing up. Trivia. She has placed first on the Dance Moms episodes "Rock That," "Ready for War," and "The Robot." She played Jasmine in two episodes of Grey's Anatomy in 2016. She sang the national anthem at a Los Angeles Clippers game at the Staples Center. She performed on tour with Mariah Carey. Family Life. She has a younger sister named Bella Blu. Her parents are named Kristie Ray and Shawn Ray. Green Print. Edited As digital technology became integral to the capitalist market dystopia of the first decades of the 21st century, it refashioned both our ways of working and our ways of consuming, as well as. Green Print. About. Merlin Press has been publishing books for over 30 years. We cover wide variety of subjects and categories with our main focus being on social & political titles covering key issues that concern all of us. For further information visit the representation page, or contact our team. Contact. Contact: Customer Services. Merlin Press, Central Books Building 50 Freshwater Rd Chadwell Heath London RM8 1RX. Jasmine's War by Daniel Hyland. Automatic capture for your stadium has arrived. Hudl Focus Outdoor records, uploads and livestreams American football and soccer games. -

Elberta Considers Sales Tax Hike

Serving the greater NORTH, CENTRAL AND SOUTH BALDWIN communities Foley man travels around the world PAGE 8 Pick an event for your family to try The Onlooker PAGE 5 AUGUST 16, 2017 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ Elberta considers sales tax hike By CLIFF MCCOLLUM increase is necessary to have “A one cent sales tax is not tax is something that would be [email protected] money to run this town,” former going to hurt me in Elberta,” predominantly charged to snow- Mayor Marvin Williams, owner Stanley said. “I really do think it birds. I suggest that before we Tensions flared during last of the Roadkill Cafe, said. “But I will hurt potential new businesses raise taxes across the board for all week’s Elberta Town Council don’t think we can live with it. I coming in, though.” the citizens.” work session, as the council dis- think it will drive people away. I Former Councilman John Conti Councilman Michael Hudson cussed a possible one percent think we ought to extinguish all urged the council to consider said his math on a possible rental sales tax increase to help raise avenues of approach before we other means of taxation as a way tax for the town would only raise money for needed road upgrades come to that.” to raise revenue. about $28,000 per year, which and a possible Elberta sports com- Steve Stanley, a longtime El- “I’d like to reiterate the point would not fully meet the infra- #Foley plex. berta resident, said he knew the made to this council and the previ- structure needs facing the town. -

Photo Gallery

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL NOW ANY SHOW) ANY GOOD TOWARD AVAILABLE! ($25 INCREMENTS, Gift Certificates — Friday, May 11 - I Write the Songs Friday, A tribute to singing legend John Denver A Wednesday, Wednesday, Greatest Manilow hits from the ’70s & ’80s Aug. 16, 2017 16, Aug. (715) 479-4421 AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS Sunday, Dec. 10 - A Rocky Mountain Christmas Sunday, Series Sponsor: Auditorium High School ALL SHOWS ALL 7:30 p.m. Northland Pines 2017-2018 For more information about tickets and shows A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A Weekdays 7 a.m.-4 p.m., Sat. 8 Sun. 9 a.m.-2 p.m. Weekdays or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, call Rick Roder at 920-676-3621. or to purchase GIFT CERTIFICATES, presents: Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. Pine St. • Eagle River 715-479-7995 Purchase tickets at Eagle River Roasters • 339 W. The world-famous “Big Band” returns Featuring the lead guitarist from “Glee” Saturday, Nov. 4 - Derik Nelson & Family Nov. Saturday, Saturday, April 21 - Glenn Miller Orchestra Saturday, (2 ADULT & 2 CHILD) ADULT (2 FAMILY PKG. FAMILY 240/ $ • (17 & UNDER) OFF single ticket prices! OFF single ticket prices! NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL CHILDREN 45/ $ 2017-2018 CONCERT SEASON • 40% 40% SEASON TICKETS ON SALE NOW! “Duck Dynasty goes to Carnegie Hall” ADULTS Broadway favorites with a touch of Gospel 90/ Save Save $ Saturday, March 3 - Redneck Tenors Saturday, Friday, Sept.Friday, 8 - The Inspiration of Broadway © Eagle River Publications, Inc. -

Gogebic Community College Holds 83Rd Commencement by IAN MINIELLY Tional Students Tend to Not Be Full Time [email protected] Or Between the Ages of 18-24

Partly cloudy High: 63 | Low: 40 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Saturday, May 13, 2017 75 cents ‘TONIGHT IS DEDICATED TO YOU’ Gogebic Community College holds 83rd commencement By IAN MINIELLY tional students tend to not be full time [email protected] or between the ages of 18-24. The stu- IRONWOOD — Gogebic Community dent has frequently already held a job College president Jim Lorenson, in his for an extended period of time, poten- welcoming remarks before introducing tially already raised a family or at least John Lupino, chairperson, for the 83rd is well on the way to raising a family. Or commencement in GCC history, said to is an adult just looking for a different the assembled students filling the career path and using an education to lindquist Center, “Tonight is dedicated achieve it. to you.” Seeing the wide variety of graduates The production required to get the Friday night before and during com- right people on stage, the faculty in two mencement, brought back the effort the lines for the graduates to navigate while school’s board and Ryon List, Dean of shuffling students through this same Instruction, are putting forth to make tunnel consisting of faculty, put the GCC available and worthwhile to people emphasis on the graduates and kept the seeking an education that transfers to a procession moving forward. follow on college or into an immediate One cannot say kids graduating when career. discussing college graduation, as many Marcia Long, the guest speaker, non-traditional students return to col- pointed out the rarified air the gradu- leges across the county every year for ates would be breathing at the conclu- additional job training, career advance- sion of the evening, when she pointed ment, or just plain old learning for the out less than 7 percent of the world has sake of learning. -

Fassio Egg Farms Starts to Cleanup After Fire

FRONT PAGE A1FRONT PAGE A1 J&J Jewelry still going strong after 27 years See A10 TOOELETRANSCRIPT SERVING TOOELE COUNTY BULLETIN SINCE 1894 THURSDAY September 7, 2017 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 124 No. 29 $1.00 Fassio Egg Farms starts to cleanup after fire STEVE HOWE ly 600,000 remaining chickens STAFF WRITER are unable to get to refrigera- A day after a fire destroyed tion quickly enough without two chicken coops and killed the conveyer system, Larsen as many as 300,000 chickens said. As a result, all of the eggs at Fassio Egg Farms in Erda, produced since the fire must employees were beginning to be disposed of, he said. clear debris. The conveyer system is “We’re cleaning up as best a priority for the farm and as we can,” said Corby Larsen, Larsen said they hope to have vice president of operations at some version of the system in Fassio Egg Farms. place within the next couple of FRANCIE AUFDEMORTE/TTB PHOTOS The two chicken coops days. The farm is also looking destroyed in the fire were con- to replace the chickens killed Ashlyn, KedRick and Melinda Hunsaker (left) listen while Adriana Padillo with The Brothers Restaurant explains about the eatery’s offerings at the Taste of Our County, Business and Career Showcase at the Benson Grist Mill on Wednesday. nected to the additional coops in the fire within the next few and processing plant by a weeks. conveyer system, which trans- Chickens in the adjacent ported the eggs, Larsen said. coops are being monitored Chamber draws big crowd to grist mill The fire used the conveyer sys- for effects from the fire and tem connection to spread from smoke, Larsen said. -

Friday Morning, Nov. 6

FRIDAY MORNING, NOV. 6 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) 78631 AM Northwest Be a Millionaire The View (N) (cc) (TV14) 64438 Live With Regis and Kelly (N) (cc) 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) 297235 (cc) 55693 86051 77902 KOIN Local 6 Early News 81631 The Early Show (N) (cc) (TVG) 65411 Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 at 6 58490 74438 99148 (TV14) 15952 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today “Sesame Street” anniversary; Jeff Corwin; Fran Drescher; makeovers. (N) (cc) (TVG) 894186 Rachael Ray (cc) (TVG) 97780 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 28761 Power Yoga Between the Lions Curious George Sid the Science Super Why! Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Big Bird & Snuffy Clifford the Big Dragon Tales WordWorld (TVY) Martha Speaks 10/KOPB 10 10 18896 (TVY) 18709 (TVY) 34235 Kid (TVY) 46070 (TVY) 59070 (TVY) 58341 Talent Show. (TVY) 27544 Red Dog 92761 (TVY) 45877 86525 (TVY) 87254 Good Day Oregon-6 (N) 79419 Good Day Oregon (N) 58815 The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) 12612 Paid 27457 Paid 63273 The Martha Stewart Show (N) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (TVG) 57186 Key of David Paid 17235 Paid 33761 Paid 52896 Through the Bible Life-Robison Paid 56525 Paid 87983 Paid 31815 Paid 52709 Paid 93457 Paid 94186 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVG) 62380 66902 65273 Praise-A-Thon (Left in Progress) Fundraising event. -

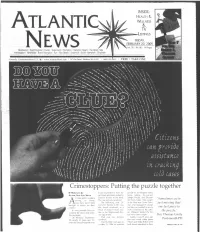

2009-02-20.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4711.9 MB

ISIE: EA & WEESS ATLANTIL\I TV SIGS IAY, EUAY 20, 200 l. . 06 I 24 rntdEWS I Et Kntn I Extr I Grnlnd I ptn I ptn h I ptn! ll Knntn I fld I rth ptn I I h I Sbr I Sth ptn I Strth Cnnll Cntn C I .Atlnt.M I 0 El Strt, Slbr, MA 02 . (60 26 I EE • AKE OE ! \ rr`r v t 4, 4 ,, k 4 .‘ 44.:"‘d !1'.'4Ajr2rvIr—4.".44..444%t:: ?r A 7 6...lp t6. • ...zn s Snn n r‘ltl l Crimestoppers: Putting the puzzle together Y MA CAG f. fnd rdrd n hr Ch t fr t n Ilntn Strt AAAMC EWS SA WIE pl Strt prtnt, lld b h lln 26rld r thr llr ln v tr t th hd. ph ln nd 2r 'Sometimes we're n td, h rn nlvd. ld rr Gl. Al ht Ah hv nvr bn h flln r, 20 n th blz nd l just missing that brht t jt fr thr rld ttl r, h nd t p r? l fnd rdrd, bt ltr bd t vr one last piece to It vr pbl. t rlt f v hd nj brn tnd n th nfr the puzzle.' ld b th n t hlp lv r, n hr Mpld Av n. Whvr trtd th fr th tr. n prtnt. h nvr bn ht. t h Grll On Mnd, Sptbr ht , t, rn tl, t 8 r rtth PD 28, nrl 0 r , 2 nlvd. th vr , hn rld r Krnptn ntthr r , n Mr nd Stll ltn r Otbr , 86, n rnt bth fnd rdrd n thr UE Ct n A• AGE 2A I AnAlsrnc EWS EUAY 20, 2009 I Vot_ 35, No 06 AtthrlCEWS.COM WEAE E WEEKE rd, brr 20 Strd, brr 2 Snd, brr 22 Mnd, brr 2 brr 24 h: ° :° h: 28° : 4° h:0° : ° h: 28° : 6° Mn 1 , . -

Voucher Program Growing Rapidly

1 TUESDAY, JULY 9, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Charter school may be cut Lack of progress Baptist Church and its proposed NE Kingston school has not corrected numer- Greater Truevine started the charter school. Lane, was set to ous deficiencies that constitute charter process three years ago. cited for proposal County School Superintendent open in August, noncompliance with the contract, They expected to open in August to cancel contract. Terry Huddleston has recom- but it has yet the letter said. 2012, but had to file an amend- mended that the School Board to meet numer- “To date, the school has failed ment to push the opening date By AMANDA WILLIAMSON terminate the charter contract ous require- to meet generally accepted stan- back by another year. [email protected] it currently has with the church ments needed dards of fiscal management, facil- “They have done very little, during the board meeting tonight Huddleston first, according ity readiness, personnel require- as of being prepared to open,” The Columbia County School at 7 p.m. in the School Board to a letter draft- ments and insurance require- in the year since, assistant District may cut ties with the Complex auditorium. ed by assistant superintendent ments, among other material Greater Truevine Missionary Vine Academy of the Arts, 217 Narragansett Smith. The charter issues,” the letter said. BOARD continued on 3A Voucher BLACK WATER CHURNS program growing rapidly Nearly 11,000 students added to non-public school rolls in past year. By BRANDON LARRABEE The News Service of Florida TALLAHASSEE — The state’s vouch- er-like system that allows students to attend private schools experienced record enrollment growth in 2012-13, according to a state report, and a spokesman said the program expects to add even more students in the upcoming year. -

37131054409156D.Pdf

YEZAD A Romance of the Unknown By GEORGE BABCOCK PUBLISHED BY CO-OPERATIVE PUBLISHING CO., INC. BRIDGEPORT, CONN. NEW YORK, N. Y. Copyright, November, 1922, by GEORGE BABCOCK All rights reserved To MY S1sTER, EVA STANTON (BABCOCK) BROWNING., this story 1s affectionately inscribed. GEORGE BABCOCK. Brooklyn, N. Y. November, 19ff. CHARACTERS l JOHN BACON, Aviator. 2 JuLIA BACON, His Wife. 3 PAUL BACON, Son. 4 ELLEN BACON, Daughter. 5 AnoLPH VON PosEN, Inventor, in love. 6 SALLY T1MPOLE, the Cook, also in love. 7 JASPER PERKINS } 8 SILAS CUMMINGS The old quaint cronies. 9 NANCY PRINDLE 10 DOCTOR PETER KLOUSE. 11 HESTER DOUGLASS} 12 F IN LEY D OU GLASS Grandchildren of the Doctor. 13 SAM WILLIS, the dreadful liar. 14 WILLIAM THADDEUS TITUS, Champion of several trades. 15 WILLIAM GRENNELL, the Village Blacksmith. 16 MINNA BACON } 17 B RENDA B ACON Children of Paul and Hester. 18 RoBERT DouGLAss, Son of Finley and Ellen. 19 CHARLOTTE Dun LEY, a Maiden of Mars. 20 CHRISTOPHER SPENCER, Astronomer of Mars. 21 FELIX CLAUDIO, the Devil's Son. 22 DocToR NATHAN ELIZABRAT of Mars. 23 MARCOMET, a Guard of the Great White \Vay. 24 JOHN BACON'S DUALITY. Note:-A Glossary of coined and unusual words and their mean ing, used by the author in Yezad, will be found on pages 449 to 463. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I THE PRICE OF PROGRESS 1 II THE GHOST • 20 III NEW NEIGHBORS 33 IV DOCTOR KLOUSE 45 V HEREDITY VS. KLOUSE PHILOSOPHY 52 VI A DREADFUL LIAR • 57 VII AMONG THE ABORIGINES 71 VIII AN ODD EXPERIMENT . -

GSN Edition 06-18-20

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, June 18, 2013 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 81, Number 49 8 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 event notice Weekend brings damaging storms By Kevin Bottrell he said. [email protected] Sherman County was mainly After a mostly dry week, a series bypassed by storms on Thursday, of evening storms dropped one and a but high winds that night damaged half inches of rain over the weekend, a half-finished fertilizer silo at bringing with them damaging wind, the Goodland Business Park. Bill hail and lighting. Schields with Crop Production Rainfall reports always vary Services said the structural strength throughout the county, The National of the silo comes from the top and Weather Service station on the bottom, and the roof hadn’t been put north end of Goodland, reported on yet. A strong gust of wind folded just .03 inches on Friday. Storms on the south side inward. Schields Saturday and Sunday dropped 1.45 said the company building the tank inches all together. for Crop Production Services has With this rain, Sherman County is experience with this sort of dam- up to 2.39 inches in June, 1.76 inch- age, and it would only set them back es above the average. The area is still This half-finished fertilizer silo at Crop Production Services was bent inward by a gust of wind on about a week. under the average for the year. The Thursday. Crews worked over the weekend to repair the damage. Speaking to the Star-News on Fri- Baseball weather service has recorded 6.75 Photo by Kevin Bottrell/The Goodland Star-News day, Floyd called Thursday a “mar- inches so far in 2013, compared to ginally severe event” and said there the average of 8.24.