The Cable Network in an Era of Digital Media: Bravo and the Constraints of Consumer Citizenship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Douglas Holloway Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Holloway, Douglas V., 1954- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Douglas Holloway, Dates: December 13, 2013 Bulk Dates: 2013 Physical 9 uncompressed MOV digital video files (4:10:46). Description: Abstract: Television executive Douglas Holloway (1954 - ) is the president of Ion Media Networks, Inc. and was an early pioneer of cable television. Holloway was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on December 13, 2013, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2013_322 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Television executive Douglas V. Holloway was born in 1954 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He grew up in the inner-city Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood. In 1964, Holloway was part of the early busing of black youth into white neighborhoods to integrate Pittsburgh schools. In 1972, he entered Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts as a journalism major. Then, in 1974, Holloway transferred to Emerson College, and graduated from there in 1975 with his B.S. degree in mass communications and television production. In 1978, he received his M.B.A. from Columbia University with an emphasis in marketing and finance. Holloway was first hired in a marketing position with General Foods (later Kraft Foods). He soon moved into the television and communications world, and joined the financial strategic planning team at CBS in 1980. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD by Steve Sternberg

April 2021 #105 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD By Steve Sternberg Last year’s upfront season was different from any I’ve been involved in during my 40 years in the business. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were no live network presentations to the industry, and for the first time since I’ve been evaluating television programming, I did not watch any of the fall pilots before the shows aired. Many new and returning series experienced production delays, resulting in staggered premieres, shortened seasons, and unexpected cancellations. The big San Diego and New York comic-cons were canceled. There was virtually no pre-season buzz for new broadcast or cable series. Stuck at home with fewer new episodes of scripted series than ever to watch on ad-supported TV, people turned to streaming services in large numbers. Netflix, which had plenty of shows in the pipeline, surged in terms of both viewers and new subscribers. Disney+, boosted by season 2 of The Mandalorian and new Marvel series, WandaVision and Falcon and the Winter Soldier, was able to experience tremendous growth. A Sternberg Report Sponsored Message The Sternberg Report ©2021 ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______ Amazon Prime Video, and Hulu also managed to substantially grow their subscriber bases. Warner Bros. announcing it would release all of its movies in 2021 simultaneously in theaters and on HBO Max (led by Wonder Woman 1984 and Godzilla vs. Kong), helped add subscribers to that streaming platform as well – as did its successful original series, The Flight Attendant. CBS All Access, rebranded as Paramount+, also enjoyed growth. -

Escuela Politécnica Nacional Facultad De Ingeniería Eléctrica Y Electrónica

ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Y ELECTRÓNICA DISEÑO DE LA CABECERA (HEAD END) DE UNA EMPRESA DE CATV PARA PROVEER TELEVISIÓN DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN (HDTV) EN LAS CIUDADES DE QUITO Y GUAYAQUIL UTILIZANDO UNA ARQUITECTURA REDUNDANTE PROYECTO PREVIO A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERO EN ELECTRÓNICA Y TELECOMUNICACIONES LOAIZA FREIRE ALBERTO GABINO [email protected] DIRECTOR: ING. FERNANDO FLORES [email protected] Quito, Noviembre 2011 DECLARACIÓN Yo Alberto Gabino Loaiza Freire, declaró bajo juramento que el trabajo aquí descrito es de mi autoría; que no ha sido previamente presentado para ningún grado o calificación profesional; y, que he consultado las referencias bibliográficas que se incluyen en este documento. A través de la presente declaración cedo mis derechos de propiedad intelectual correspondientes a este trabajo, a la Escuela Politécnica Nacional, según lo establecido por la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, por su Reglamento y por la normatividad institucional vigente. Alberto Gabino Loaiza Freire CERTIFICACIÓN Certifico que el presente trabajo fue desarrollado por ALBERTO GABINO LOAIZA FREIRE, bajo mi supervisión. Ing. Fernando Flores DIRECTOR DE PROYECTO AGRADECIMIENTO A mi Esposa Daisy Elena por su ayuda y apoyo incondicional. Al Ing. Pablo Vega por su colaboración desinteresada para el desarrollo de este proyecto. Al Ing. Fernando Flores por su acertada guía durante la elaboración de este proyecto. A Grupo TVCable por el auspicio y el apoyo brindado en la realización de este proyecto. DEDICATORIA Se lo dedico muy especialmente al amor de mi vida, a la compañera de mi vida, a mi esposa Daisy Elena. Se lo dedico también a mi familia: a mi Madre que ha sido un ejemplo de vida, a mis hermanas Alex y Carla por el apoyo incondicional en todo momento, y a mi Padre por creer y confiar siempre en mí. -

A Hermeneutic Historical Study of Kazimierz Dabrowski and His Theory of Positive Disintegration

A Hermeneutic Historical Study of Kazimierz Dabrowski and his Theory of Positive Disintegration Marjorie M. Kaminski Battaglia Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Development Dr. Marcie Boucouvalas, Chair Dr. M. Gerald Cline, Research Chair Dr. Clare Klunk Dr. Linda Morris Dr. Karen Rosen March 20, 2002 Falls Church, Virginia Keywords: Positive Disintegration, Human Development, Hermeneutic, transpersonal, TPD, Dabrowski Copyright 2002, Marjorie M. Kaminski Battaglia Abstract A Hermeneutic Historical Study of Kazimierz Dabrowski and his Theory of Positive Disintegration Marjorie M. Kaminski Battaglia The inquiry is a hermeneutic historical study of the historical factors in the life of Kazimierz Dabrowski which contributed to the shaping of his Theory of Positive Disintegration. Relatively little information has been written on the life and theory of Kazimierz Dabrowski. The researcher contends that knowledge of Dabrowski, the man, will aid in an understanding of his theory. The journey in which an individual “develops” to the level at which “the other” becomes a higher concern than the self, is the “stuff” of Kazimierz Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration. It is a paradoxical theory of human development, based on the premise that “good can follow from bad.” Crisis and suffering act as the propellents into an internal as well as external battle with self and environment to move out of the “what is” and travel to the “what ought to be.” Illuminated within this study, is how the life of Dabrowski demonstrates this moral and psychic struggle. -

From Broadcast to Broadband: the Effects of Legal Digital Distribution

From Broadcast to Broadband: The Effects of Legal Digital Distribution on a TV Show’s Viewership by Steven D. Rosenberg An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2007 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Jarl G. Kallberg Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Legal Digital Distribution............................................................................................. 6 2.1 iTunes ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Streaming ................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Current thoughts ...................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Financial importance ............................................................................................. 12 3. Data Collection ............................................................................................................ 13 3.1 Ratings data ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Repeat data ............................................................................................................ -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

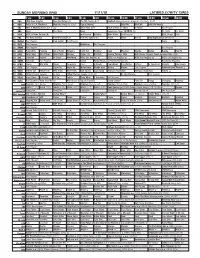

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

Female Journalists in Candace Bushnell Novels

From Carrie to Nico: Female Journalists in Candace Bushnell Novels By Stephanie Wenger From Carrie to Nico: Female Journalists in Candace Bushnell Novels 2 Abstract This work examines the image of the female journalist in five novels by Candace Bushnell. Each novel features a female journalist who struggles to balance her demanding job and private life. This paper explores how the female protagonists in these modern novels differ and the ways in which they fit into the major stereotypes of female journalists. This paper will look at the characters’ professional lives, relationships with the opposite sex, and moral compasses. This paper also examines how the protagonists in the novels Sex and the City and Lipstick Jungle differ from their television counterparts. Lastly, this work will look at how Candace Bushnell’s images of the journalist fit into larger social theories about women in the media. From Carrie to Nico: Female Journalists in Candace Bushnell Novels 3 Introduction “Chick lit,” a pop culture abbreviation for chick literature, is a growing sector of the $23-billion publishing industry.1 This genre of books is considered to a subsection of women’s fiction and features “everyday women in their 20s and 30s navigating their generation’s challenges of balancing demanding careers with personal relationships.”2 These books made publishers $71 million in 2002 according to ABC News.3 Sessalee Hensely, a fiction buyer for giant retailer Barnes & Noble, explains, “The mega authors John Grisham, Michael Crichton, Tom Clancy all have had a fall-off in sales, but the chick lit is growing and they’re growing exponentially.”4 The increase in sales of these novels has made Hollywood take notice. -

(“JCRA”) Decision M622/10 Acquisition of Virgin Media

Jersey Competition Regulatory Authority (“JCRA”) Decision M622/10 Acquisition of Virgin Media Television Rights Limited and Virgin Media Television Limited by British Sky Broadcasting Group plc The Notified Transaction 1. On 13 August 2010, the JCRA received an application (the “ Application ”) for approval under Articles 20 and 21 of the Competition (Jersey) Law 2005 (the “Law ”) concerning the acquisition of Virgin Media Television Rights Limited and Virgin Media Television Limited, together with the rights to all assets used exclusively in the Virgin Media television business acquisition (together: “VMTV ”) by British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (“ Sky ”), through the intermediary Kestrel Broadcasting Limited. 2. The JCRA published a notice of its receipt of the Application in the Jersey Gazette and on its website on 17 August 2010, inviting comments on the Acquisition by 31 August 2010. During this period, the JCRA received one written submission concerning the Acquisition. This submission is discussed in more detail in paragraph 29 below. In addition to public consultation, the JCRA conducted its own market enquiries concerning the Acquisition. 3. In addition to Jersey, the parties stated that the acquisition had been notified with the relevant authorities in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. On 29 June 2010 the Irish Competition Authority approved the Acquisition. The JCRA has had contact with the Office of Fair Trading (“ OFT ”), the UK authority, regarding the acquisition. The Parties (a) Sky 4. Sky is incorporated in England and Wales and its shares are listed on the London Stock Exchange. The worldwide turnover in the year ending June 2009 was approximately £5.4 billion. -

Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: the Image of the Journalist As a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’S Sex and the City

Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: The Image of the Journalist as a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’s Sex and the City By Bibi Wardak Abstract New York Star sex columnist Carrie Bradshaw lives the life of a celebrity in HBO’s Sex and the City. She mingles with the New York City elite at extravagant parties, dates the city’s most influential men and enjoys the adoration of fans. But Bradshaw echoes the image of many female journalists in popular culture when it comes to romance. Bradshaw is thirty-something, unmarried and unsure about having children. Despite having a successful career and loyal friends, she feels unfulfilled after each failed romantic relationship. I. Introduction “A wildly successful career and a relationship -- I was afraid…women only get one or the other.”1 That’s a fear Carrie Bradshaw just can’t shake. The sex columnist for the New York Star is unmarried, career-oriented and unsure if she will ever have a traditional family.2 Just like other modern sob sisters, she is romantically unfulfilled and has sacrificed aspects of her personal life for professional success.3 Bradshaw, played by Sarah Jessica Parker in HBO’s hit television show Sex and the City, portrays a stereotypical image of female journalists found in television and film.4 She and other female journalists in the series struggle to balance a successful Knowing Good Sex Pays Off: The Image of the Journalist as a Famous, Exciting and Chic Sex Columnist Named Carrie Bradshaw in HBO’s Sex and the City By Bibi Wardak 2 career and satisfying romantic life.