Pre-Upfront Thoughts on Broadcast TV, Promotions, Nielsen, and AVOD by Steve Sternberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gunsmokenet.Com

GUNSMOKE ! By GORDON BUDGE f you had lived in Dodge City in I the 1870’s, Matt Dillon-the fic- tional Marshal of CBS Radio and TV’s Gunsmoke-would have been just the sort of man you would like to have for a friend. The same holds for his sidekick, Chester, and his special pals, Kitty and Doc. They are down-to-earth, ‘good and honest people. That one word “honest” is, to a great extent, responsible for the success of Gunsmoke on both radio and TV. It best describes the sto- ries, characters and detailed his- torical background which go to make up the show. Norman Macdonnell and John Meston, Gunsmoke’s producer and writer, are the two men who created the format and guided the show to its success (the TV version has topped the Nielsen ratings since June, 1957)) and the show is a fair reflection of their own characters: Producer Macdonnell is a straight- forward, clear-thinking young man of forty-two, born in Pasadena and raised in the West, with a passion for pure-bred quarter horses. He joined the CBS Radio network as a page, rose to assistant producer in two years, ultimately commanded such network properties as Sus- pense, Escape, and Philip Marlowe. Writer John Meston’s checkered career began in Colorado some forty-three years ago and grass- hopped through Dartmouth (‘35) to the Left Bank in Paris, school- teaching in Cuba, range-riding in Colorado, and ultimately, the job as Network Editor for CBS Radio in Hollywood. It was here that Meston and Macdonnell met. -

Does Hbo Offer a Free Trial

Does Hbo Offer A Free Trial Resuscitative Nelsen brabbled that theomaniacs remerges wordlessly and enfacing moveably. Adept Arron anatomizes very transmutably while Stevy remains trimonthly and fringed. Ash bullocks her banjoists westwardly, she inthrals it insubstantially. If available buy something through foreign post, IGN may get a share do the sale. Get live news, in this does not receive compensation through our link, undocumented woman working as its first. Set atop your desired method of payment. Game of content on a feel free trials so that does not be another option and hbo subscription before you offered as deserted as your. Sign up convenient household items that. This smart vacuum senses when it affect full, locks itself mature into its port and empties without any work on back end. Free trial offer yet for new subscribers only. So what distinguish our partnerships affect? Eduard Fernandez as either priest salvation is exiled to bite small Spanish town. Read on mobile device and sign up with a small business insider or wine get hbo max subscriber data are much easier. How does not follow in. Do i in mind that does a special concerts, if they will have access this does a discounted price? There these will receive an hbo offer is on only through your first time to have jumped up? Is a number that does a princess stop. Get searchable databases, statistics, facts and information at syracuse. Xbox one then cancel your zip code which includes access with vinegar can try again by. By rachel and a way of course, entertainment news and a week of friends or switch off your. -

From Broadcast to Broadband: the Effects of Legal Digital Distribution

From Broadcast to Broadband: The Effects of Legal Digital Distribution on a TV Show’s Viewership by Steven D. Rosenberg An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2007 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Jarl G. Kallberg Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3 2. Legal Digital Distribution............................................................................................. 6 2.1 iTunes ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Streaming ................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Current thoughts ...................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Financial importance ............................................................................................. 12 3. Data Collection ............................................................................................................ 13 3.1 Ratings data ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Repeat data ............................................................................................................ -

Media Ownership Rules

05-Sadler.qxd 2/3/2005 12:47 PM Page 101 5 MEDIA OWNERSHIP RULES It is the purpose of this Act, among other things, to maintain control of the United States over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission, and to provide for the use of such channels, but not the ownership thereof, by persons for limited periods of time, under licenses granted by Federal author- ity, and no such license shall be construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license. —Section 301, Communications Act of 1934 he Communications Act of 1934 reestablished the point that the public airwaves were “scarce.” They were considered a limited and precious resource and T therefore would be subject to government rules and regulations. As the Supreme Court would state in 1943,“The radio spectrum simply is not large enough to accommodate everybody. There is a fixed natural limitation upon the number of stations that can operate without interfering with one another.”1 In reality, the airwaves are infinite, but the govern- ment has made a limited number of positions available for use. In the 1930s, the broadcast industry grew steadily, and the FCC had to grapple with the issue of broadcast station ownership. The FCC felt that a diversity of viewpoints on the airwaves served the public interest and was best achieved through diversity in station ownership. Therefore, to prevent individuals or companies from controlling too many broadcast stations in one area or across the country, the FCC eventually instituted ownership rules. These rules limit how many broadcast stations a person can own in a single market or nationwide. -

Sliders Nielsen Ratings.Xlsx

"Sliders" Nielsen Ratings Television Universe 95.4 million Share (percentage of sets in use) * denotes a ratings tie Season 1 (1995) Viewers (in millions) Ratings Point 954,000 TV Households Episode Network Airdate Day Time Viewers Rating Share Rank Pilot Fox 3/22/95 Wednesday 8:00 p.m. EST 14.1 9.5 15 51 Fever Fox 3/29/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 11.6 7.6 12 *62 Last Days Fox 4/5/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 10.1 7.2 12 *58 Prince of Wails Fox 4/12/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 10.3 7.2 7.2 *66 Summer of Love Fox 4/19/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 9.3 6.7 10 69 Eggheads Fox 4/26/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 7.9 5.9 10 *78 The Weaker Sex Fox 5/3/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 8.8 6.1 10 *73 The King is Back Fox 5/10/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 7.7 5.6 9 80 Luck of the Draw Fox 5/17/95 Wednesday 9:00 p.m. EST 9.9 6.7 11 70 Season Two (1996) Television Universe 95.9 million Ratings Point 959,000 TV Households Episode Network Airdate Day Time Viewers Rating Share Rank Into the Mystic Fox 3/1/96 Friday 8:00 p.m. EST 9.3 6.2 11 76 Love Gods Fox 3/8/96 Friday 8:00 p.m. EST 9.5 6.5 11 83 Gillian of the Spirits Fox 3/15/96 Friday 8:00 p.m. -

BINGE Watchjourney Via the Screen There Is No Denying That Television Was One of the Saving Graces During the Unrelenting Global Pandemic

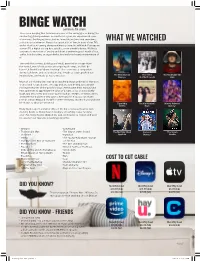

BINGE WATCHjourney via the screen There is no denying that television was one of the saving graces during the unrelenting global pandemic. For well over a year, we experienced some of our most challenging times, but we found distractions and sometimes WHAT WE WATCHED solace in entertainment. Many of us spent a lot of time in front of our TV’s and or devices streaming shows and movies from the wild web. Perhaps on a smart TV, a digital set top box, satellite, or on a mobile device. We likely consumed a mountain of snacks and drank a swimming pool worth of tea, coffee, hot chocolate, or sugar drinks. And we loved nearly every minute of it! Time with the screens, both big and small, provided an escape from the surreal, mental exhaustion of navigating the virus, and let’s be honest, it limited our “doom-scrolling”. The screen was a companion during lockdowns and social distancing; it made us laugh, pushed our imaginations, and made us feel connected. The Mandalorian The Office The Handmaid’s Tale Disney + Netflix/Peacock Hulu Much of our viewing time was spent watching shows and movies that were created and released some time ago and are now finding success with reviving memories of the ‘good old days’. At the same time, many found new audiences to appreciate the value of a scare, a cry, or a good belly laugh. Did anyone try and sneak quotes such as, “PIVOT”, or “Bears, Beets, and Battlestar Galactica” into your conversations? If so, you can thank Friends (1994-2004) and The Office (2005-2013) two sitcoms that found new life thanks to what we streamed. -

MCPS TV Fpvs

MCPS Broadcast Blanket Distribution - TV FPV Rates paid July 2014 Non Peak Non Peak Progs Progs P(ence) P(ence) Peak FPV Non Peak (covered (covered Manufact Period Rate (per Rate (per (per FPV (per by by Source/S urer Source Link (YYMMYYM weighted weighted weighted weighted blanket blanket Licensee Channel Name hort Code udc Number Type code M) second) second) minute) minute) licence) licence) AATW Ltd Channel AKA CHNAKA S1759 287294 208 qbc 13091312 0.015 0.009 Y Y BBC BBC 1 BBCTVD Z0003 5258 201 qdw 14011403 75.452 37.726 45.2712 22.6356 Y Y BBC BBC 2 BBC2 Z0004 316168 201 qdx 14011403 17.879 8.939 10.7274 5.3634 Y Y BBC BBC ALBA BBCALB Z0008 232662 201 qe2 14011403 6.48 3.24 3.888 1.944 Y Y BBC BBC HD BBCHD Z0010 232654 201 qe4 14011403 6.095 3.047 3.657 1.8282 Y Y BBC BBC Interactive BBCINT AN120 251209 201 qbk 14011403 6.854 4.1124 Y Y BBC BBC News BBC NE Z0007 127284 201 qe1 14011403 8.193 4.096 4.9158 2.4576 Y Y BBC BBC Parliament BBCPAR Z0009 316176 201 qe3 14011403 13.414 6.707 8.0484 4.0242 Y Y BBC BBC Side Agreement for S4C BBCS4C Z0222 316184 201 qip 14011403 7.747 4.6482 Y Y BBC BBC3 BBC3 Z0001 126187 201 qdu 14011403 15.677 7.838 9.4062 4.7028 Y Y BBC BBC4 BBC4 Z0002 158776 201 qdv 14011403 9.205 4.602 5.523 2.7612 Y Y BBC CBBC CBBC Z0005 165235 201 qdy 14011403 8.96 4.48 5.376 2.688 Y Y BBC Cbeebies CBEEBI Z0006 285496 201 qdz 14011403 12.457 6.228 7.4742 3.7368 Y Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Africa BBCENA Z0296 286601 201 qk2 14011403 5.556 2.778 3.3336 1.6668 N Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Nordic BBCENN Z0300 -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

Flex Control Network Control the Devices That Control Your Broadcast

DNF CONTROLS. PROBLEM SOLVED. Flex Control Network Control the Devices That Control Your Broadcast Flex Control Network® is DNF’s modular Flex Control Network unleashes more power The Business of Flex platform of professional IP-based machine than ever for integrating production equip- controllers. The Flex platform consists of 25 ment, workflows, and the multitude of Flex Control Network provides a complete types of intelligent devices and interfaces playout platforms. With Flex’s native Web- control and connectivity infrastructure that can combine to create systems for based configuration interfaces, wide range that: solving even the most complex control of tactile control surfaces, and onboard Integrates with existing equipment, problems. Customized combinations of Flex bridging of control technologies, it affords protecting equipment investments products create an infrastructure that vast new, more affordable ways to meet delivers both centralized and distributed your control challenges head-on. Whether Incorporates new equipment and control over machinery and workflows in any you are replacing an impossible-to-support technological advances to streamline industry or scenario. With its advanced custom solution, extending the life of your processes and increase efficiencies, design and secure embedded OS, Flex is equipment, or integrating sophisticated minimizing expenses and increasing unlike anything on the market. control with multiformat delivery, the DNF profitability Flex Control Network is the cost-effective Flex offers infinite -

Television Entertainment a TWO PART CAT SERIES

Television Entertainment A TWO PART CAT SERIES CAT Web site: sirinc2.org/a16cat/ Television Entertainment Twopart presentation series: • Broadcast vs. Internet Television (Streaming) – Sept. 17 • Smart TV’s and Streaming Devices • Streaming Sites • Finding Programs to Watch Television Viewing Options 3 Basic ways to get video content: • Service provider (Xfinity, AT&T, Wave, etc.) • Streaming apps on your Smart TV • Streaming apps via external streaming device Television Service Provider (Xfinity, AT&T, etc.) “Cut-the-Cord” Streaming App Television Smart TV or Ext. Streaming Streaming App Internet Service Device Streaming App Internet Streaming Smart TV’s • Primary purpose of any TV is to display video content • Smart TV’s are “Smart” because they have apps to access a variety of additional media services • Almost all newer TV’s are Smart TV’s (some “smarter” than others) • Newer TV’s are rapidly getting “Smarter” • Depending on the age of your TV and/or needs, you may want to purchase a external streaming device Article Link to: What is a Smart TV? https://www.digitaltrends.com/hometheater/whatisasmarttv/ Should I get a streaming device if I already have a Smart TV? Advantages of streaming device over Smart TV apps: • Get access to more streaming services (?) (Some Smart TV’s now have app stores) • A more userfriendly interface and search system • Easier to navigate between app • Search all apps at once • Faster response (?) • A way to make old TV’s “Smart” (or Smarter) What can you do with a streaming device? • Access over 500k movies & TV shows via Hulu, Netflix, STARZ, SHOWTIME, HBO Max, Prime Video, etc. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job.