Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Expressionism: the Second Generation (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988): 10-37

Stephanie Barron, “Introduction” to Barron (ed.), German Expressionism: The Second Generation (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1988): 10-37. The notion that all the significant achievements of German Expressionism occurred before 1914 is a familiar one. Until recently most scholars and almost all exhibitions of German Expressionist work have drawn the line with the 1913 dissolution of Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Berlin or the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Peter Selz’s pioneering study German Expressionist Painting, published in 1957, favored 1914 as a terminus as did Wolf-Dieter Dube’s Expressionism, which appeared in 1977. It is true that by 1914 personal differences had led the Brücke artists to dissolve their association, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) had disintegrated when Wassily Kandinsky returned from Munich to Russia and Franz Marc volunteered for war service. Other artists’ associations also broke up when their members were drafted. Thus, the outbreak of the war has provided a convenient endpoint for many historians, who see the postwar artistic activities of Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, Oskar Kokoschka, Kathe Kollwitz, and others as individual, not group responses and describe the 1920s as the period of developments at the Bauhaus in Weimar or of the growing popularity of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). The years 1915-25 have been lost, or certainly not adequately defined, as a coherent and potent, albeit brief, idealistic period in the evolution of German Expressionism. More recent scholarship, including Dube’s Expressionists and Expressionism (1983) and Donald E. Gordon’s Expressionism- Art and Idea (1987), sees the movement as surviving into the 1920s. -

Vorlesungsverzeichnis Wise 2012/13

Technische Universität Chemnitz Philosophische Fakultät & Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften __________________________________________________________ Kommentiertes Vorlesungsverzeichnis der interfakultären Studiengänge Europa-Studien Kulturwissenschaftliche Ausrichtung Sozialwissenschaftliche Ausrichtung Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Ausrichtung Wintersemester 2012/13 (Stand 19.09.2012) Zum Geleit Sehr geehrte Studentinnen und Studenten, dieses kommentierte Vorlesungsverzeichnis umfasst die Lehrveranstaltungen der Studienordnungen 2009 und 2012 für alle Semester. Die Lehrveranstaltungen sind gegliedert in Kern- und Vertiefungsstudium. Bei Fragen zum Vorlesungsverzeichnis oder zur Stundenplangestaltung können Sie sich an die Fachstudienberater wenden. Die Kontaktinformationen finden Sie auf der letzten Seite! Ein erfolgreiches Wintersemester 2012/13 wünscht Ihnen Ihr Fachbereich Europa-Studien KVV WiSe12/13 ES 2 Inhalt I. Termine zum Semesterablauf: Wintersemester 2012/13 .................................... 5 II. Hinweise - Übergang StOrd 2009 zu StOrd 2012................................................ 7 III. Lehrveranstaltungen – Kernstudium ................................................................. 8 Modul: B1 ................................................................................................................ 9 Modul: B2 (StOrd 2009), B2a/b (StOrd (2012) ...................................................... 11 Modul: B3 ............................................................................................................. -

Otto Dix (1891-1969) War Triptych, 1929-32

Otto Dix (1891-1969) War Triptych, 1929-32 Key facts: Date: 1929-32 Size: Middle panel: 204 x 204 cm; Left and right wing each 204 x 102 cm; Predella: 60 x 204 cm Materials: Mixed media (egg tempera and oil) on wood Location: Staatliche Kunstammlungen, Dresden 1. ART HISTORICAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS Subject Matter: The Great War is a history painting within a landscape set out over four panels, a triptych with a predella panel below. The narrative begins in the left panel, the soldiers in their steel helmets depart for war through a thick haze, already doomed in Dix’s view. In the right panel, a wounded soldier is carried from the battlefield, while the destructive results of battle are starkly depicted in the central panel. This is a bleak and desolate landscape, filled with death and ruin, presided over by a corpse. Trees are charred, bodies are battered and torn and lifeless. War has impacted every part of the landscape. (This panel was a reworking on an earlier painting Dix had done entitled The Trench, 1920-3. David Crocket wrote: “many, if not most, of those who saw this painting in Cologne and Berlin during 1923-24 knew nothing about this aspect of the war.” The predella scene shows several soldiers lying next to one another. Perhaps they are sleeping in the trenches, about to go back into the cycle of battle when they awake, or perhaps they have already fallen and will never wake again. Dix repeatedly depicted World War I and its consequences after having fought in it himself as a young man. -

E 13 George Grosz (1893-1959) 'My New Pictures'

272 Rationalization and Transformation this date (1920) have sat in a somewhat strained relationship with the more overtly left-vi elements of the post-war German avant-garde. Originally published in Edschmid, op. cit. ~~g present translation is taken from Miesel, op. cit., pp. 180-1. e Work! Ecstasy! Smash your brains! Chew, stuff your self, gulp it down, mix it around! Th bliss of giving birth! The crack of the brush, best of all as it stabs the canvas. Tubes ~ 0 color squeezed dry. And the body? It doesn't matter. Health? Make yourself healthy! Sickness doesn't exist! Only work and I'll say that again - only blessed work! Paint' Dive into colors, roll around in tones! in the slush of chaos! Chew the broken-off mouthpiece of your pipe, press your naked feet into the earth. Crayon and pen pierce sharply into the brain, they stab into every corner, furiously they press into the whiteness. Black laughs like the devil on paper, grins in bizarre lines, comforts in velvety planes, excites and caresses. The storm roars - sand blows about - the sun shatters to pieces - and nevertheless, the gentle curve of the horizon quietly embraces everything. Beaten down, exhausted, just a worm, collapse into your bed. A deep sleep will make you forget your defeat. A new day! A new struggle! Ecstasy again! One day after the other, a sparkling, constantly changing chain of days. One experience after the other. That damned brain! What is it that churns and twitches and jumps in there? Hah! Tear your head off, or grab it with both hands, turn it around, twist it off. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

![Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6290/kurt-schwitterss-merzbau-chaos-compulsion-and-creativity-author-s-clare-o-dowd-source-moveabletype-vol-696290.webp)

Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[s]: Clare O’Dowd Source: MoveableType, Vol. 5, ‘Mess’ (2009) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.046 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2009 Clare O’Dowd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Moveable Type Vol. 5 2009: CLARE O’DOWD 1 Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau : Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity For nearly thirty years until his death in 1948, the German artist Kurt Schwitters constructed environments for himself: self-contained worlds, places of safety, nests. Everywhere he went he stockpiled materials and built them into three-dimensional, sculptural edifices. By the time he left Hanover in 1937, heading for exile in England, Schwitters, his wife, his son, his parents, their lodgers, and a large number of guinea pigs had all been living in the midst of an enormous, detritus-filled sculpture that had slowly engulfed large parts of their home for almost twenty years. 1 Schwitters was by no means the only artist to have a cluttered studio, or to collect materials for his work. So the question must be asked, what was it about Schwitters’ activities that was so unusual? How can these and other aspects of his work and behaviour be considered to go beyond what might be regarded as normal for an artist working at that time? And more importantly, what were the reasons for this behaviour? In this paper, I will examine the beginnings of the Merzbau , the architectural sculpture that Schwitters created in his Hanover home. -

Hannah Höch 15 January – 23 March 2014 Galleries 1, 8 & Victor Petitgas Gallery (Gallery 9)

Hannah Höch 15 January – 23 March 2014 Galleries 1, 8 & Victor Petitgas Gallery (Gallery 9) The Whitechapel Gallery presents the first major UK exhibition of the influential German artist Hannah Höch (1889-1978). Hannah Höch was an important member of the Berlin Dada movement and a pioneer in collage. Splicing together images taken from popular magazines, illustrated journals and fashion publications, she created a humorous and moving commentary on society during a time of tremendous social change. Acerbic, astute and funny, Höch established collage as a key medium for satire whilst being a master of its poetic beauty. Höch created some of the most radical works of the time and was admired by contemporaries such as George Grosz, Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters, yet she was often overlooked by traditional art history. At a time when her work has never seemed more relevant, the exhibition puts this inspiring figure in the spotlight. Bringing together over 100 works from major international collections, the exhibition includes collages, photomontages, watercolours and woodcuts, spanning six decades from the 1910s to the 1970s. Highlights include major works such as Staatshäupter (Heads of State) (1918-20) and Flucht (Flight) (1931) as well as her innovative post-war collages. This exhibition charts Höch’s career beginning with early works influenced by her time working in the fashion industry to key photomontages from her Dada period, such as Hochfinanz (High Finance) (1923), which sees notable figures collaged together with emblems of industry in a critique of the relationship between financiers and the military at the height of an economic crisis in Europe. -

German and Austrian Art of the 1920S and 1930S the Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection

German and Austrian Art of the 1920s and 1930s The Marvin and Janet Fishman Collection The concept Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) was introduced in Germany in the 1920s to account for new developments in art after German and Austrian Impressionism and Expressionism. Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub mounted an exhibition at the Mannheim Museum in 1925 under the title Neue Art of the1920s and1930s Sachlichkeit giving the concept an official introduction into modern art in the Weimar era of Post-World War I Germany. In contrast to impressionist or abstract art, this new art was grounded in tangible reality, often rely- ing on a vocabulary previously established in nineteenth-century realism. The artists Otto Dix, George Grosz, Karl Hubbuch, Felix Nussbaum, and Christian Schad among others–all represented in the Haggerty exhibi- tion–did not flinch from showing the social ills of urban life. They cata- logued vividly war-inflicted disruptions of the social order including pover- Otto Dix (1891-1969), Sonntagsspaziergang (Sunday Outing), 1922 Will Grohmann (1887-1968), Frauen am Potsdamer Platz (Women at Postdamer ty, industrial vice, and seeds of ethnic discrimination. Portraits, bourgeois Oil and tempera on canvas, 29 1/2 x 23 5/8 in. Place), ca.1915, Oil on canvas, 23 1/2 x 19 3/4 in. café society, and prostitutes are also common themes. Neue Sachlichkeit artists lacked utopian ideals of the Expressionists. These artists did not hope to provoke revolutionary reform of social ailments. Rather, their task was to report veristically on the actuality of life including the ugly and the vulgar. Cynicism, irony, and wit judiciously temper their otherwise somber depictions. -

Ein Biogra Scher Garten Der Garten Der Familie Dix in Hemmenhofen

Ein biograscher Garten Der Garten der Familie Dix in Hemmenhofen s war ein wildes Gemisch aus kräigen Far- Frau Martha und den Kindern Nelly (13), Ursus (9) und «Eben », so erinnert sich Jan Dix an die Blumen- Jan (8) zog er 1936 auf die Halbinsel Höri nach Hemmen- sträusse, die seine Muer Martha und seine Schwester hofen, gegenüber von Steckborn am deutschen Ufer des Nelly aus dem Garten der Familie des Malers Oo Dix Bodensees. Die Höri war bereits anfangs des 20. Jahrhun- zusammenstellten. « Schwefelgelbe Schafgarbe neben derts als ländlicher Sehnsuchtsort von Lebensreformern nachtschwarzen Malven, vielerlei Formen und komple- und Künstlern entdeckt worden, unter ihnen auch Her- mentäre Farben, dicht gedrängte, starrköpge Zinnien mann Hesse, der sich 1907 im benachbarten Gaienhofen in ihren unwahrscheinlich reichen Farbnuancen waren für fünf Jahre niedergelassen hae. Die Dixens gehörten Motive für Blumenbilder. Kapuzinerkresse, Schwertlilie, zu einer zweiten Generation von Höri-Künstlern, die sich Nelke, alles o in Portraits als Aribut verwendet, wurde in in der Zeit der Nazi-Diktatur wohl oder übel aus dem Hemmenhofen im Garten angepanzt und gepegt. » Vom öentlichen Leben haen zurückziehen müssen. Oo Dix, Garten auf die Leinwand des Vaters waren es nur wenige der « Grossstadtmensch », pegte zeitlebens ein gespalte- Schrie. Und auch wenn Oo Dix weder Blumenmaler nes Verhältnis zu seinem neuen Lebensort, den er bis zu noch Gärtner genannt werden kann, so sind Panzenbeob- seinem Tod 1969 beibehielt. « Zum Kotzen schön », so achtungen aus dem Garten doch vielfach in seine Arbeiten Dix, sei diese Landscha, die er in den Zeiten der inne- eingeossen, wurde der Garten zum geliebten und gestalte- ren Emigration gleichwohl oder gerade deswegen immer ten Zuhause für ihn und seine Familie. -

Otto Dix, Letters, Vol.1

8 Letters vol. 1 1904–1927 Translated by Mark Kanak Translation © 2016 Mark Kanak. .—ıst Contra Mundum Press Edition Otto Dix, Briefe © 2014 by 290 pp., 6x 9 in. Wienand Verlag GmbH isbn 9781940625188 First Contra Mundum Press Edition 2016. I. Dix, Otto. II. Title. All Rights Reserved under III. Kanak, Mark. International & Pan-American IV. Translator. Copyright Conventions. V. Ulrike Lorenz, Gudrun No part of this book may be Schmidt. reproduced in any form or by VI. Introduction. any electronic means, including information storage and retrieval 2016943764 systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Dix, Otto, 1891–1969 [Briefe. English.] Letters, Vol. 1, 1904–1927 / Otto Dix; translated from the original German by Mark Kanak ToC Introduction 0–xxvii About This Edition xxviii–xlv Letters 0–215 Object Shapes Form 218–220 8 Introduction Ulrike Lorenz An Artist’s Life in Letters “I’ve never written confessions since, as closer inspection will reveal, my paintings are confessions of the sincerest kind you will find, quite a rare thing in these times.” — Otto Dix to Hans Kinkel (March 29, 1948) An Artist without Manifestœs A man of words, this letter writer never was. In re- sponse to art critic Hans Kinkel’s request to contribute to a collection of self-testimonials of German painters, Dix gruffly rebuked him, surly calling such pieces noth- ing but “vanity, subjective chatter.”1 And this in the precarious postwar situation, as the 57-year-old —. -

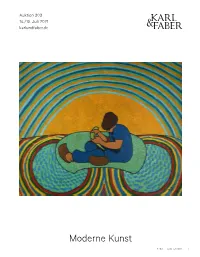

Moderne Kunst

Auktion 303 14./15. Juli 2021 karlundfaber.de Moderne Kunst 7.2021 KARL & FABER 1 2 KARL & FABER 7.2021 7.2021 KARL & FABER 3 Auktion 303 14./15. Juli 2021 KARL & FABER Kunstauktionen · Amiraplatz 3 · 80333 München Moderne Kunst Modern Art INHALT / INDEX Wassily Kandinsky, Titelholzschnitt für den Almanach Der Blaue Reiter, Los 500 LOS / LOT 500 – 553 Teil I – Ausgewählte Werke / Part I – Selected Works S. 17 Vorherige Seite: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paysage avec femme assise au milieu, Los 506 LOS / LOT 600 – 801 Teil II / Part II S. 139 Emil Nolde, „Meer“ (Welle), Los 522 Gabriele Münter, Bei Gärtnerei Mederer (?) Murnau, Los 529 Edvard Munch, Der Kuss IV, Los 501 Hans Hartung, T-1970-H37, Los 551 KONTAKT KARL & FABER MÜNCHEN / CONTACT KARL & FABER MUNICH TERMINE DATES Mittwoch, 14. Juli 2021 – Auktionen 303/304 Wednesday, 14 July 2021 – Auctions 303/304 Moderne & Zeitgenössische Kunst Modern & Contemporary Art KARL & FABER Kunstauktionen 14 Uhr Moderne Kunst Teil II Los 600–801 2 pm Modern Art Part II Lot 600–801 Amiraplatz 3 · Luitpoldblock 16.30 Uhr Zeitgenössische Kunst Teil II Los 1000–1247 4.30 pm Contemporary Art Part II Lot 1000–1247 80333 München · Germany T +49 89 22 18 65 Donnerstag, 15. Juli 2021 – Auktionen 303/304/305 Thursday, 15 July 2021 – Auctions 303/304/305 F +49 89 22 83 350 Sonderauktion „WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC“ Special auction „WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC“ [email protected] Moderne & Zeitgenössische Kunst – Ausgewählte Werke Modern & Contemporary Art – Selected Works 15.30 Uhr WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC Los 2100–2208 3.30 pm WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC Lot 2100–2208 ÖFFENTLICH BESTELLTE UND VEREIDIGTE AUKTIONATOREN / PUBLICLY APPOINTED AND SWORN AUCTIONEERS 18 Uhr Moderne Ausgewählte Werke Los 500–553 6 pm Modern Art – Selected Works Lot 500–553 19 Uhr Zeitgenössische Ausgewählte Werke Los 900–950 7 pm Contemporary Art – Selected Works Lot 900–950 Dr.