STATUS and MEAT CONSUMPTION in POMPEII: Diet and Its Social Implications Through the Analysis of Ancient Primary Sources and Zooarchaeological Remains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloth Bear Zoo Experiences 3000

SLOTH BEAR ZOO EXPERIENCES 3000 Behind the Scenes With the Tigers for Four (BEHIND THE SCENES) Head behind the scenes for a face-to-face visit with Woodland Park Zoo’s new Malayan tigers. This intimate encounter will give you exclusive access to these incredible animals. Meet our expert keepers and find out what it’s like to care for this critically endangered species. You’ll learn about Woodland Park Zoo and Panthera’s work with on-the-ground partners in Malaysia to conserve tigers and the forests which these iconic big cats call home, and what you can do to help before it’s too late. Restrictions: Expires July 10, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance. Participants must be 12 years of age and older. THANK YOU: WOODLAND PARK ZOO EAST TEAM VALUE: $760 3001 Behind the Scenes Giraffe Feeding for Five (BEHIND THE SCENES) You and four guests are invited to meet the tallest family in town with this rare, behind-the-scenes encounter. Explore where Woodland Park Zoo’s giraffe spend their time off exhibit and ask our knowledgeable keepers everything you’ve ever wanted to know about giraffe and their care. You’ll even have the opportunity to help the keepers feed the giraffe a snack! This is a tall experience you won’t forget, and to make sure you don’t, we’ll send you home with giraffe plushes! Restrictions: Expires April 30, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance from 9:30 a.m.–2:00 p.m. -

Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia Without Proper Restraint Device

J Vet Clin 26(1) : 113-116 (2009) Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled Out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia without Proper Restraint Device Hwan-Yul Yong1, Suk-Hyun Park, Myoung-Keun Choi, So-Young Jung, Dae-Chang Ku, Jong-Tae Yoo, Mi-Jin Yoo, Mi-Hyun Yoo, Kyung-Yeon Eo, Yong-Gu Yeo, Shin-Keun Kang and Heon-Youl Kim Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon 427-080, Korea (Accepted : January 28, 2009 ) Abstract : A 4-year-old female reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata), at Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon, Korea had a male calf with no help of proper restraint devices. The mother giraffe was in a danger of dystocia more than 7 hours in labor after showing the calf’s toe of the foreleg which protruded from her vulva. After tugging with a snare of rope on the metacarpal bone of the calf and pulling it, the other toe emerged. Finally, with two snares around each of metacarpal bones, the calf was completely pulled out by zoo staff. After parturition, the dam was in normal condition for taking care of the calf and her progesterone hormone had also dropped down to a normal pre-pregnancy. Key words : giraffe, dystocia, rope, parturition. Introduction giraffe. Because a giraffe is generally known as having such an uneventful gestation and not clearly showing appearances Approaching the megavertebrate species such as ele- of body with which zoo keepers notice impending parturi- phants, rhinoceroses and giraffes without anesthetic agents or tion until just several weeks before parturition. A few of zoo proper physical restraint devices is very hard, and it is even keepers were not suspicious of her being pregnant when they more difficult when it is necessary to stay near to the ani- saw the extension of the giraffe’s abdomen around 2 weeks mals for a long period (1,2,5). -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

University Manual This Manual Is Authored By: Palazzi Office of Communications, Grace Joh

PALAZZIFlorence Association For International Education FUA Florence University of the Arts 2012/ 2013 University Manual This manual is authored by: Palazzi Office of Communications, Grace Joh Revised and Edited by: Gabriella Ganugi, Palazzi Founder and President Copyright © 2012 Palazzi FAIE, All rights reserved. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS WhAT IS PALAzzI Vision, Mission, Values p. 4 Palazzi Campuses, Locations, Accreditation and Facilities p. 5 Palazzi Academic Institutions p. 7 Palazzi Affiliations p. 16 ACAdEMICS AT PALAzzI Schools and departments p. 17 Academic Policies p. 19 PALAzzI STudy ABrOAd PrOGrAMS p. 22 Semester/year - Fall and Spring, January Intersession, Summer Sessions Short and Quarter Programs - Fall and Spring PALAzzI uNdErGrAduATE PrOGrAMS p. 24 General Education requirements, Communication & Interactive digital Multimedia, Hospitality Management, Liberal Arts PALAzzI GrAduATE PrOGrAMS Customized, Service Learning, Master in Organizational Management with Endicott College, p. 27 Master in Sustainable urban design, Summer 9-Week Graduate hospitality Apprenticeship PALAzzI CArEEr PrOGrAMS p. 32 APICIuS International School of hospitality p. 33 Baking and Pastry - Culinary Arts - Master in Italian Cuisine Hospitality Management - Wine Studies and Enology DIVA digital Imaging and Visual Arts p. 58 Visual Communication Photography FAST - Fashion Accessory Studies and Technology p. 72 Accessory design and Technology Fashion design and Technology IdEAS - School of Interior design, Environmental Architecture and Sustainability p. 84 Eco-sustainable design Luxury design J SChOOL - 1 year Program in Publishing p. 96 Concentrations in Art, Fashion and Food Publishing ITALIAN LANGuAGE PrOGrAMS AT SQuOLA p. 104 SErVICE LEArNING at the School of Professional Studies p. 105 Internships, Community Service, Volunteer Work MINGLE department of Customized Programs p. -

Giraffe Are the World's Tallest Animal, They Can Reach 5.8 Metres Tall

Animal welfare refers to an animal’s state or it’s feelings. An animal’s welfare state can be positive, neutral or negative. An animal’s welfare has the potential to differ on a daily basis. When an animal’s needs - nutritional, behavioural, health and environmental - are met, they can have good welfare. A good life in captivity might be one where animals can consistently experience good welfare throughout their entire life. Understanding that animals are sentient and have cognitive abilities as well as pain perception, reinforces the need to provide appropriate husbandry for all captive animals, to ensure they have good welfare. In captivity, the welfare of an animal is dependent on the physical and behavioural environment provided for them and the daily care and veterinary treatment they receive. It is therefore very important we understand their behavioural and physiological needs, so we can meet those needs in captivity. Giraffe are the world's tallest animal, they can reach 5.8 metres tall. They are found across sub-Sahara Africa in dry forest, shrubland and savannah habitats. The current understanding is there are nine sub-species of giraffe although it is now thought they are separated into four distinct species. The giraffe is classified by the IUCN as vulnerable to extinction. It is estimated there are less than 70,000 giraffe left in the wild and the population is declining. This is due to habitat loss and hunting. Giraffes like to Eat Giraffes are herbivores, they can eat up to 45 kg of leaves, bark and twigs a day. -

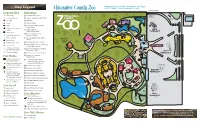

Map Legend 10001 W

Map Legend 10001 W. Bluemound Rd., Milwaukee, WI 53226 414-771-3040 www.milwaukeezoo.org Milwaukee County Zoo Bluemound Rd. Legend Key Buildings Auto teller 8 Animal Health Center Walk-In Entrance Zoofari Change Machine 9 Aquatic & Reptile Center (ARC) Drive-in Exit Animal Health Entrance Conference Center Center First Aid 0 Australia Sea Lion Birds Food - Dairy Complex Show g s Gifts = Dohmen Family Foundation Special Hippo Home Exhibit Handicap/Changing Macaque Island Zebra Station q Family Farm & Public Affairs Office Flamingo Parking Lot Information Swan w Florence Mila Borchert Lost Children’s Area Big Cat Country Fish, an Frogs & angut Mold-a-Rama e Herb & Nada Mahler Family Expedition Snakes Or Primates Apes Aviary Welcome Penny Press Dinosaur Center Summer Gorilla r Holz Family Impala Country 2015 Penguins j Private Picnic Areas ARC Bonobo t Idabel Wilmot Borchert Flamingo Theatre Rest Rooms Siamang Exhibit and Overlook Small Mammals Ropes Courses h Strollers sponsored & y Karen Peck Katz Conservation Zip Line by Wilderness Resort Education Center Giraffe Tornado Shelter u Kohl’s Cares for Kids Play Area Parking Lot i Northwestern Mutual Zoo Rides Family Farm Carousel sponsored African e Briggs o A. Otto Borchert Family Waterhol & Stratton by Penzeys Spices Special Exhibits Building a Zoo ebr Terrace Z Safari Train sponsored B. Jungle Birthday Room Lion by North Shore Bank Cheet Family p Peck Welcome Center Big African Kohl’s Farm Cats Savanna Wild ah Theater Sky Safari sponsored Sky JaguarT [ Primates of the World iger Safari South Live alks by PNC* Prairie America Grizzly Bear Snow Animal T Dairy Elephant ] Small Mammals Building Caribou Dogs Leopard Bongo Barn SkyTrail® Explorer Black Parking Lot Elk Bear Red Hippo Butterfly \ Stackner Animal Encounter Panda Garden Butterfly Ropes Courses & Zip Garden Camel W Line sponsored by a Stearns Family Apes of Africa arthog Bee Pachyderm Hive Exhibit Tri City National Bank* Tapir Pachyderm s Taylor Family Humboldt Penguins d Zoomobile sponsored Education d U.S. -

Taro Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae

Taro Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae) Ordnung: Froschlöffelartige (Alismatales) Familie: Aronstabgewächse (Araceae) Unterfamilie: Aroideae Gattung: Colocasia Art: Taro Wissenschaftlicher Name Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott Traditioneller Taroanbau auf Terrassen aus Lavagestein auf der Insel Kauaʻi Taro (Colocasia esculenta) ist eine Nutzpflanze aus der Familie der Aronstabgewächse (Araceae), die seit mehr als 2000 Jahren als Nahrungspflanze kultiviert wird. Ein anderer Name für Taro ist Wasserbrotwurzel. In alten Nachschlagewerken, wie z. B. Pierer's Universal-Lexikon findet sich für die Pflanze auch die Bezeichnung Tarro. Genutzt werden vorwiegend die stärkehaltigen Rhizome der Pflanze. Sie werden wie Kartoffeln gekocht. In den Anbauländern werden auch die Blätter und Blattstiele als Gemüse gegessen. Sie enthalten viel Mineralien, Vitamin A, B und C. Taro wird heute weltweit in feuchten, tropischen und subtropischen Klimazonen angebaut. Für den Export wird er in Ägypten, Costa Rica, der Karibik, Brasilien und Indien angepflanzt. In Hawaii ist die dort kalo[1] genannte Pflanze eine der wichtigsten traditionellen Nutzpflanzen. Aus den Rhizomen wird poi, eine Paste, hergestellt. Die Aborigines in Australien nutzen diese Pflanze um daraus Busch-Brot zu backen, indem sie aus dem Rhizom Mehl herstellten. Siehe auch [Bearbeiten] Sumpfpflanzen Wasserpflanzen Weblinks [Bearbeiten] Rhizome der Taro Commons: Taro – Album mit Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien Taro – eine Nahrungs- und eine Giftpflanze Beschreibung und Verwendungsmöglichkeit Einzelnachweise [Bearbeiten] 1. ↑ taro, kalo in Hawaiian Dictionaries Von „http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taro― Kategorien: Aronstabgewächse | Nutzpflanze | Blattgemüse | Wurzelgemüse Taro From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the plant. For other uses, see Taro (disambiguation). It has been suggested that this article or section be merged with Colocasia esculenta. -

Each of the 30 Printable Bingo Cards Below Contains the English

Each of the 30 printable bingo cards below contains the English translation for 24 words randomly drawn from the set of words in the award-winning Linguacious™ Animals vocabulary flashcard game, available in many different foreign languages. Suggestions for how to use this bingo game to help kids acquire vocabulary in the foreign language of your choice can be found on our website: www.linguacious.net crab whale fox walrus rabbit snake frog cat monkey bee rhinoceros sheep owl starfish polar bear hen giraffe bird cow snail buffalo duck tiger eagle To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. deer dog camel whale frog rhinoceros sheep walrus starfish turtle polar bear mouse ostrich dolphin zebra eagle bee bear fish snake penguin buffalo owl grasshopper To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. ladybug fox starfish monkey lion squirrel dog turtle crab camel snake dolphin duck ostrich penguin fish polar bear spider horse tiger elephant grasshopper goat owl To access the foreign language version of each of these words and hear their pronunciation by a native speaker of that language, visit www.linguacious.net or use the award-winning Linguacious™ vocabulary flashcards or posters, also available on our website. -

Some Account of the Cuisine Bourgeoise of Ancient Rome

283 XV.—Some Account of the Cuisine Bourgeoise of Ancient Rome. By H. C. COOTE, Esq. F.S.A. Bead December 13th, 1866. No one has yet written the history of the Roman palate, such as it became when the successes of that people had given occasion for its artificial cultivation. The Roman, consequently, has never been contemplated on this side of his character. This is not merely an omission in archaeology, it is a blank left in the annals of taste. And the omission is the more remarkable, as most other subjects of antiquity have been fathomed by the learned, down even to the shoe and the caliga. This subject alone caret vate sacro.a In saying this I do not of course mean that the subject has not been imperfectly touched upon, for all the world is familiar with the rhombus of Domitian, the mullus trilibris of Horace, the oysters of Rutupium, and the slave-fed murence of Yidius Pollio; while the dishes of nightingales' tongues served up to that inventive madman Helio- gabalus, and the culinary wonders of the Augustan writers, are known alike to learned and unlearned. But all these allusions have been fragmentary merely, meant to point a feeble moral,—not to expound principles of the cuisine. In a word, the writers have never thought of treating Roman cookery en cuisinier—the only way in which the subject can afford a rational interest to any one. Virtually, therefore, this subject has been left untouched by these authors. There is no excuse, however, for this neglect of Roman Cookery, for the amplest materials exist for its mastery and complete illustration. -

Critical Area Vocabulary Reader

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=C Critical Area Vocabulary Reader DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=A CorrectionKey=A CorrectionKey=A Vocabulary Critical Area Addition and Subtraction Critical Area Pacing Chart Reader Introduction Chapters Assessment Total Vocabulary Performance by John Hudson Reader Assessment 1 day 71 days 1 day 73 days 1 READ The giraffe is the tallest land animal in the All About Animals world. Adult giraffes are 13 to 17 feet tall. Objective Use literature to review addition concepts. Newborn giraffes are about 6 feet tall. A group of 5 giraffes drinks water at a Genre Nonfiction watering hole. A group of 5 giraffes eats leaves from trees. How many giraffes are there in all? 10 Domains: Operations and Algebraic Thinking CRITICAL AREA Building fl uency with addition and subtraction — giraffes © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company • Image ©DavidTipling/Getty Images Credits: © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company • Image © Credits: Eric Nathan/Alamy © Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company • Image ©Stan Credits: Osolinski/Photolibrary/Getty Images Number and Operations in Base Ten 151 152 How do giraffes care for their young? DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=A CorrectionKey=A CorrectionKey=A c Preparing to Read Refer children to the 2_MCAESE341999_U2O.indd 151 2/8/14 8:03 AM 2_MNLESE341999_U2O.indd 152 2/26/14 7:16 PM story cover and read the title. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Shamans and Symbols

SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS PREHISTORY OF SEMIOTICS IN ROCK ART Mihály Hoppál International Society for Shamanistic Research Budapest 2013 Cover picture: Shaman with helping spirits Mohsogollokh khaya, Yakutia (XV–XVIII. A.D. ex: Okladnikov, A. P. 1949. Page numbers in a sun symbol ex: Devlet 1998: 176. Aldan rock site ISBN 978-963-567-054-3 © Mihály Hoppál, 2013 Published by International Society for Shamanistic Research All rights reserved Printed by Robinco (Budapest) Hungary Director: Péter Kecskeméthy CONTENTS List of Figures IX Acknowledgments XIV Preface XV Part I From the Labyrinth of Studies 1. Studies on Rock Art and/or Petroglyphs 1 2. A Short Review of Growing Criticism 28 Part II Shamans, Symbols and Semantics 1. Introduction on the Beginning of Shamanism 39 2. Distinctive Features of Early Shamans (in Siberia) 44 3. Semiotic Method in the Analysis of Rock “Art” 51 4. More on Signs and Symbols of Ancient Time 63 5. How to Mean by Pictures? 68 6. Initiation Rituals in Hunting Communities 78 7. On Shamanic Origin of Healing and Music 82 8. Visual Representations of Cognitive Evolution and Community Rituals 92 Bibliography and Further Readings 99 V To my Dito, Bobo, Dodo and to my grandsons Ákos, Magor, Ábel, Benedek, Marcell VII LIST OF FIGURES Part I I.1.1. Ritual scenes. Sagan Zhaba (Baykal Region, Baykal Region – Okladnikov 1974: a = Tabl. 7; b = Tabl. 16; c = Tabl. 17; d = Tabl. 19. I.1.2. From the “Guide Map” of Petroglyhs and Sites in the Amur Basin. – ex: Okladnikov 1981. No. 12. = Sikachi – Alyan rock site.