Post-Colonial Heraldry in Kwazulu-Natal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloth Bear Zoo Experiences 3000

SLOTH BEAR ZOO EXPERIENCES 3000 Behind the Scenes With the Tigers for Four (BEHIND THE SCENES) Head behind the scenes for a face-to-face visit with Woodland Park Zoo’s new Malayan tigers. This intimate encounter will give you exclusive access to these incredible animals. Meet our expert keepers and find out what it’s like to care for this critically endangered species. You’ll learn about Woodland Park Zoo and Panthera’s work with on-the-ground partners in Malaysia to conserve tigers and the forests which these iconic big cats call home, and what you can do to help before it’s too late. Restrictions: Expires July 10, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance. Participants must be 12 years of age and older. THANK YOU: WOODLAND PARK ZOO EAST TEAM VALUE: $760 3001 Behind the Scenes Giraffe Feeding for Five (BEHIND THE SCENES) You and four guests are invited to meet the tallest family in town with this rare, behind-the-scenes encounter. Explore where Woodland Park Zoo’s giraffe spend their time off exhibit and ask our knowledgeable keepers everything you’ve ever wanted to know about giraffe and their care. You’ll even have the opportunity to help the keepers feed the giraffe a snack! This is a tall experience you won’t forget, and to make sure you don’t, we’ll send you home with giraffe plushes! Restrictions: Expires April 30, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance from 9:30 a.m.–2:00 p.m. -

Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia Without Proper Restraint Device

J Vet Clin 26(1) : 113-116 (2009) Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled Out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia without Proper Restraint Device Hwan-Yul Yong1, Suk-Hyun Park, Myoung-Keun Choi, So-Young Jung, Dae-Chang Ku, Jong-Tae Yoo, Mi-Jin Yoo, Mi-Hyun Yoo, Kyung-Yeon Eo, Yong-Gu Yeo, Shin-Keun Kang and Heon-Youl Kim Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon 427-080, Korea (Accepted : January 28, 2009 ) Abstract : A 4-year-old female reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata), at Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon, Korea had a male calf with no help of proper restraint devices. The mother giraffe was in a danger of dystocia more than 7 hours in labor after showing the calf’s toe of the foreleg which protruded from her vulva. After tugging with a snare of rope on the metacarpal bone of the calf and pulling it, the other toe emerged. Finally, with two snares around each of metacarpal bones, the calf was completely pulled out by zoo staff. After parturition, the dam was in normal condition for taking care of the calf and her progesterone hormone had also dropped down to a normal pre-pregnancy. Key words : giraffe, dystocia, rope, parturition. Introduction giraffe. Because a giraffe is generally known as having such an uneventful gestation and not clearly showing appearances Approaching the megavertebrate species such as ele- of body with which zoo keepers notice impending parturi- phants, rhinoceroses and giraffes without anesthetic agents or tion until just several weeks before parturition. A few of zoo proper physical restraint devices is very hard, and it is even keepers were not suspicious of her being pregnant when they more difficult when it is necessary to stay near to the ani- saw the extension of the giraffe’s abdomen around 2 weeks mals for a long period (1,2,5). -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

Giraffe Are the World's Tallest Animal, They Can Reach 5.8 Metres Tall

Animal welfare refers to an animal’s state or it’s feelings. An animal’s welfare state can be positive, neutral or negative. An animal’s welfare has the potential to differ on a daily basis. When an animal’s needs - nutritional, behavioural, health and environmental - are met, they can have good welfare. A good life in captivity might be one where animals can consistently experience good welfare throughout their entire life. Understanding that animals are sentient and have cognitive abilities as well as pain perception, reinforces the need to provide appropriate husbandry for all captive animals, to ensure they have good welfare. In captivity, the welfare of an animal is dependent on the physical and behavioural environment provided for them and the daily care and veterinary treatment they receive. It is therefore very important we understand their behavioural and physiological needs, so we can meet those needs in captivity. Giraffe are the world's tallest animal, they can reach 5.8 metres tall. They are found across sub-Sahara Africa in dry forest, shrubland and savannah habitats. The current understanding is there are nine sub-species of giraffe although it is now thought they are separated into four distinct species. The giraffe is classified by the IUCN as vulnerable to extinction. It is estimated there are less than 70,000 giraffe left in the wild and the population is declining. This is due to habitat loss and hunting. Giraffes like to Eat Giraffes are herbivores, they can eat up to 45 kg of leaves, bark and twigs a day. -

Roetman Coat of Arms

Wartburg Castle The Most Distinguished Surname Roetman Certificate No.320685201638 Copyright 1998-2016 Swyrich Corporation. All Rights Reserved www.houseofnames.com 888-468-7686 Table of Contents Surname History Ancient History 3 Spelling Variations 3 Early History 3 Early Notables 4 The Great Migration 4 Current Notables 4 Surname Symbolism Introduction 6 Motto 6 Shield 7 Crest 8 Further Readings and Bibliography Bibliography 10 Certificate No.320685201638 Copyright 1998-2016 Swyrich Corporation. All Rights Reserved www.houseofnames.com 888-468-7686 Ancient History The history of the name Roetman brings us to Thuringia, a modern state located between Hessen and Lower Saxony in the west and Saxony in the east. Originally a Kingdom of the Germanic tribe of the Hermunderen, the land was conquered by the Franks and the Saxons in 531. A.D. In 634, King Dagobert appointed Radulf duke of the Thuringians, and the land became virtually independent under his rule. However, Charles Martel abolished the position of duke and brought Thuringia under the rule of Franconian counts, and divided up the territory. The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne founded the Thuringian Mark (border region) in 804 as a defensive bulwark against the power of the Slavic peoples. In the Middle Ages the name Roetman has been traced back to Thuringia, where the family was known for its contributions to the prosperity and culture of the emerging feudal society. The family branched into numerous houses, many of which acquired estates and manors throughout the surrounding regions. Spelling Variations Throughout the development and evolution of a name's history, variations in spelling and pronunciation frequently occur. -

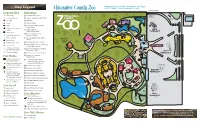

Map Legend 10001 W

Map Legend 10001 W. Bluemound Rd., Milwaukee, WI 53226 414-771-3040 www.milwaukeezoo.org Milwaukee County Zoo Bluemound Rd. Legend Key Buildings Auto teller 8 Animal Health Center Walk-In Entrance Zoofari Change Machine 9 Aquatic & Reptile Center (ARC) Drive-in Exit Animal Health Entrance Conference Center Center First Aid 0 Australia Sea Lion Birds Food - Dairy Complex Show g s Gifts = Dohmen Family Foundation Special Hippo Home Exhibit Handicap/Changing Macaque Island Zebra Station q Family Farm & Public Affairs Office Flamingo Parking Lot Information Swan w Florence Mila Borchert Lost Children’s Area Big Cat Country Fish, an Frogs & angut Mold-a-Rama e Herb & Nada Mahler Family Expedition Snakes Or Primates Apes Aviary Welcome Penny Press Dinosaur Center Summer Gorilla r Holz Family Impala Country 2015 Penguins j Private Picnic Areas ARC Bonobo t Idabel Wilmot Borchert Flamingo Theatre Rest Rooms Siamang Exhibit and Overlook Small Mammals Ropes Courses h Strollers sponsored & y Karen Peck Katz Conservation Zip Line by Wilderness Resort Education Center Giraffe Tornado Shelter u Kohl’s Cares for Kids Play Area Parking Lot i Northwestern Mutual Zoo Rides Family Farm Carousel sponsored African e Briggs o A. Otto Borchert Family Waterhol & Stratton by Penzeys Spices Special Exhibits Building a Zoo ebr Terrace Z Safari Train sponsored B. Jungle Birthday Room Lion by North Shore Bank Cheet Family p Peck Welcome Center Big African Kohl’s Farm Cats Savanna Wild ah Theater Sky Safari sponsored Sky JaguarT [ Primates of the World iger Safari South Live alks by PNC* Prairie America Grizzly Bear Snow Animal T Dairy Elephant ] Small Mammals Building Caribou Dogs Leopard Bongo Barn SkyTrail® Explorer Black Parking Lot Elk Bear Red Hippo Butterfly \ Stackner Animal Encounter Panda Garden Butterfly Ropes Courses & Zip Garden Camel W Line sponsored by a Stearns Family Apes of Africa arthog Bee Pachyderm Hive Exhibit Tri City National Bank* Tapir Pachyderm s Taylor Family Humboldt Penguins d Zoomobile sponsored Education d U.S. -

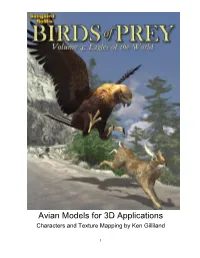

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Texture Mapping by Ken Gilliland

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Texture Mapping by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix BIRDS of PREY Volume IV: Eagles of the World Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview 3 Poser and DAZ Studio Use 3 Physical-based Renderers 4 Where to find your birds 4 Morphs and their Use 5 Field Guide List of Species 10 Sea or Fish Eagles Bald Eagle 11 African Fish-eagle 14 Pallas's Fish-eagle 16 Booted Eagles Golden Eagle 18 Greater Spotted Eagle 21 Martial Eagle 24 Steppe Eagle 27 Wedge-tailed Eagle 29 Snake Eagles Philippine Eagle 32 Short-toed Snake-eagle 35 Crested Serpent-eagle 37 Harpy or Giant Forest Eagles Harpy Eagle 40 Mountain Hawk-eagle 43 Ornate Hawk-eagle 46 African Crowned Hawk-eagle 48 Resources, Credits and Thanks 52 To my Mor and Morfar.... Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher. Copyrighted 2015-18 by Ken Gilliland (SongbirdReMix.com) 2 Songbird ReMix BIRDS of PREY Volume IV: Eagles of the World Introduction Eagles are large and powerfully built birds of prey. They have elongated heads, heavy beaks and long, broad wings. There are sixty species of eagles; most of which are found in Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just fourteen species can be found – two in the United States and Canada, nine in Central and South America, and three in Australia. Eagles are informally divided into four groups; Fish Eagles, Booted Eagles, Snake Eagles, and Harpy Eagles. Sea eagles or fish eagles take fish as a large part of their diets, either fresh or as carrion. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial Name: Loch Soilleir, Barony of Date Registered: 9/30/2006 Mantling 1: Argent Helm: Barred Helm argent, visor or Helm Facing: dexter Mantling 2: Sable: a semy of compass stars arg Crest verte a sea serpent in annulo volant of Motto Inspiration Endeavor Strength Translation Inspiration Endeavor Strength it's tail Corone baronial Dexter Supporter Sea Ram proper Sinister Supporter Otter rampant proper Notes inside of helm is gules, Sea Ram upper portion white ram, lower green fish. Sits on 3 waves Azure and Argent instead of the normal mound Name: Adelicia Tagliaferro Date Registered: 4/22/1988 Mantling 1: counter-ermine Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: argent Crest owl Or Motto Honor is Duty and Duty is Honor Translation Corone baronial wide fillet Dexter Supporter owl Or Sinister Supporter owl Or Notes Lozenge display with cloak; originally registered 4\22\1988 under previous name "Adelicia Alianora of Gilwell" Name: Aeruin ni Hearain O Chonemara Date Registered: 6/28/1988 Mantling 1: sable Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: vert Crest heron displayed argent crested orbed Motto Sola Petit Ardea Translation The Heron stands alone (Latin) and membered Or maintaining in its beak a sprig of pine and a sprig of mistletoe proper Corone Dexter Supporter Sinister Supporter Notes Display with cloak and bow Name: Aethelstan Aethelmearson Date Registered: 4/16/2002 Mantling 1: vert ermined Or Helm: Spangenhelm with brass harps on the Helm Facing: Afronty Mantling 2: Or cheek pieces and brass brow plate Crest phoenix -

Special Issue: 2012 Hans Christian Andersen Award Nominees Would You Like to Write for IBBY’S Journal?

VOL. 50, NO.2 APRIL 2012 Special Issue: 2012 Hans Christian Andersen Award Nominees Would you like to write for IBBY’s journal? Academic Articles ca. 4000 words The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Bookbird publishes articles on children’s literature with an international perspective four times a year Copyright © 2012 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editors. (in January, April, July and October). Articles that compare literatures of different countries are of interest, as are papers on translation studies and articles that discuss the reception of work from one country in Editors: Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta—Augustana Faculty (Canada) and Lydia Kokkola, University of Turku another. Articles concerned with a particular national literature or a particular book or writer may also be (Finland) suitable, but it is important that the article should be of interest to an international audience. Some issues Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] are devoted to special topics. Details and deadlines of these issues are available from Bookbird’s web pages. Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Augustana Faculty at the University of Alberta, Camrose, Alberta, Canada. Children and their Books ca. 2500 words Editorial Review Board: Peter E. Cumming, York University (Canada); Debra Dudek, University of Wollongong Bookbird also provides a forum where those working with children and their literature can write about (Australia); Libby Gruner, University of Richmond (USA); Helene Høyrup, Royal School of Library & Information their experiences. -

The Constitution of Zimbabwe

THE CONSTITUTION OF ZIMBABWE As amended to No.16 of 20 April 2000 (Amendments in terms of Act No.5 of 2000 (Amendment No.16) are at sections 16, 16A (Land Acquisition) and 108A (Anti-Corruption Commission)) CHAPTER 1- THE REPUBLIC AND THE CONSTITUTION Article 1 The Republic Zimbabwe is a sovereign republic and shall be known as “the Republic of Zimbabwe”. [Section as amended by section 2 of Act 30 of 1990 - Amendment No.11] Article 2 Public seal There shall be a public seal of Zimbabwe, showing the coat of arms of Zimbabwe with the inscription “Republic of Zimbabwe”, which shall be kept by the President. [Section as amended by section 3 of Act 30 of 1990 - Amendment No.11] Article 3 Supreme law This Constitution is the supreme law of Zimbabwe and if any other law is inconsistent with this Constitution that other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void. CHAPTER 2- CITIZENSHIP Article 4 Citizens of Zimbabwe on Independence A person who, immediately before the appointed day, was or was deemed to be a citizen by birth, descent or registration shall, on and after that day, be a citizen of Zimbabwe by birth, descent or registration, as the case may be. Article 5 Citizenship by birth (1) A person born in Zimbabwe on or after the appointed day but before the date of commencement of the Constitution of Zimbabwe Amendment (No.14) Act, 1996, shall be a citizen of Zimbabwe by birth, unless— (a) at the time of his birth, his father— (i) possesses such immunity from suit and legal process as is accorded to the envoy of a foreign sovereign