Title: Some Reflections Concerning the Usage of "Liquamen" in the Roman Cookery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

University Manual This Manual Is Authored By: Palazzi Office of Communications, Grace Joh

PALAZZIFlorence Association For International Education FUA Florence University of the Arts 2012/ 2013 University Manual This manual is authored by: Palazzi Office of Communications, Grace Joh Revised and Edited by: Gabriella Ganugi, Palazzi Founder and President Copyright © 2012 Palazzi FAIE, All rights reserved. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS WhAT IS PALAzzI Vision, Mission, Values p. 4 Palazzi Campuses, Locations, Accreditation and Facilities p. 5 Palazzi Academic Institutions p. 7 Palazzi Affiliations p. 16 ACAdEMICS AT PALAzzI Schools and departments p. 17 Academic Policies p. 19 PALAzzI STudy ABrOAd PrOGrAMS p. 22 Semester/year - Fall and Spring, January Intersession, Summer Sessions Short and Quarter Programs - Fall and Spring PALAzzI uNdErGrAduATE PrOGrAMS p. 24 General Education requirements, Communication & Interactive digital Multimedia, Hospitality Management, Liberal Arts PALAzzI GrAduATE PrOGrAMS Customized, Service Learning, Master in Organizational Management with Endicott College, p. 27 Master in Sustainable urban design, Summer 9-Week Graduate hospitality Apprenticeship PALAzzI CArEEr PrOGrAMS p. 32 APICIuS International School of hospitality p. 33 Baking and Pastry - Culinary Arts - Master in Italian Cuisine Hospitality Management - Wine Studies and Enology DIVA digital Imaging and Visual Arts p. 58 Visual Communication Photography FAST - Fashion Accessory Studies and Technology p. 72 Accessory design and Technology Fashion design and Technology IdEAS - School of Interior design, Environmental Architecture and Sustainability p. 84 Eco-sustainable design Luxury design J SChOOL - 1 year Program in Publishing p. 96 Concentrations in Art, Fashion and Food Publishing ITALIAN LANGuAGE PrOGrAMS AT SQuOLA p. 104 SErVICE LEArNING at the School of Professional Studies p. 105 Internships, Community Service, Volunteer Work MINGLE department of Customized Programs p. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Taro Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae

Taro Taro (Colocasia esculenta) Systematik Unterklasse: Froschlöffelähnliche (Alismatidae) Ordnung: Froschlöffelartige (Alismatales) Familie: Aronstabgewächse (Araceae) Unterfamilie: Aroideae Gattung: Colocasia Art: Taro Wissenschaftlicher Name Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott Traditioneller Taroanbau auf Terrassen aus Lavagestein auf der Insel Kauaʻi Taro (Colocasia esculenta) ist eine Nutzpflanze aus der Familie der Aronstabgewächse (Araceae), die seit mehr als 2000 Jahren als Nahrungspflanze kultiviert wird. Ein anderer Name für Taro ist Wasserbrotwurzel. In alten Nachschlagewerken, wie z. B. Pierer's Universal-Lexikon findet sich für die Pflanze auch die Bezeichnung Tarro. Genutzt werden vorwiegend die stärkehaltigen Rhizome der Pflanze. Sie werden wie Kartoffeln gekocht. In den Anbauländern werden auch die Blätter und Blattstiele als Gemüse gegessen. Sie enthalten viel Mineralien, Vitamin A, B und C. Taro wird heute weltweit in feuchten, tropischen und subtropischen Klimazonen angebaut. Für den Export wird er in Ägypten, Costa Rica, der Karibik, Brasilien und Indien angepflanzt. In Hawaii ist die dort kalo[1] genannte Pflanze eine der wichtigsten traditionellen Nutzpflanzen. Aus den Rhizomen wird poi, eine Paste, hergestellt. Die Aborigines in Australien nutzen diese Pflanze um daraus Busch-Brot zu backen, indem sie aus dem Rhizom Mehl herstellten. Siehe auch [Bearbeiten] Sumpfpflanzen Wasserpflanzen Weblinks [Bearbeiten] Rhizome der Taro Commons: Taro – Album mit Bildern, Videos und Audiodateien Taro – eine Nahrungs- und eine Giftpflanze Beschreibung und Verwendungsmöglichkeit Einzelnachweise [Bearbeiten] 1. ↑ taro, kalo in Hawaiian Dictionaries Von „http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taro― Kategorien: Aronstabgewächse | Nutzpflanze | Blattgemüse | Wurzelgemüse Taro From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the plant. For other uses, see Taro (disambiguation). It has been suggested that this article or section be merged with Colocasia esculenta. -

Some Account of the Cuisine Bourgeoise of Ancient Rome

283 XV.—Some Account of the Cuisine Bourgeoise of Ancient Rome. By H. C. COOTE, Esq. F.S.A. Bead December 13th, 1866. No one has yet written the history of the Roman palate, such as it became when the successes of that people had given occasion for its artificial cultivation. The Roman, consequently, has never been contemplated on this side of his character. This is not merely an omission in archaeology, it is a blank left in the annals of taste. And the omission is the more remarkable, as most other subjects of antiquity have been fathomed by the learned, down even to the shoe and the caliga. This subject alone caret vate sacro.a In saying this I do not of course mean that the subject has not been imperfectly touched upon, for all the world is familiar with the rhombus of Domitian, the mullus trilibris of Horace, the oysters of Rutupium, and the slave-fed murence of Yidius Pollio; while the dishes of nightingales' tongues served up to that inventive madman Helio- gabalus, and the culinary wonders of the Augustan writers, are known alike to learned and unlearned. But all these allusions have been fragmentary merely, meant to point a feeble moral,—not to expound principles of the cuisine. In a word, the writers have never thought of treating Roman cookery en cuisinier—the only way in which the subject can afford a rational interest to any one. Virtually, therefore, this subject has been left untouched by these authors. There is no excuse, however, for this neglect of Roman Cookery, for the amplest materials exist for its mastery and complete illustration. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

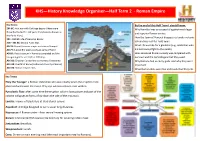

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Food Heritage and Nationalism in Europe

Chapter 4 Food and locality Heritagization and commercial use of the past Paolo Capuzzo Geographical roots of food? Identifying a food culture with a locality has always involved a trade-off between searching for roots and recognizing they are not planted in any one spot but entail exchanges and borrowings from remote origins. But even this tension between the local and the supralocal is a simplification: it rests on the assumption that food cultures can be identified by place alone. Actually, highly different food regimes may be at work in one and the same place, and have been so in the past. Class stratification may afford a first prism dividing up food culture domains, but it then interweaves with gender, religious observance, ethnic belonging and so on. Does this mean that any attempt to find a relationship between food and place is a waste of effort? No, indeed: such a relationship can definitely be established. But one does need a critical analysis of the various factors bearing on the link between food and place, since they are cultural and historical constructs rather than causal connections between milieus in nature/history and food cultures. A cuisine rich in victuals of different kinds, prepared from a wide range of ingredients at times exotic in provenance, was typical of the food culture found in the courts of Europe from the late Middle Ages to the early modern era; the diet of the people was more closely locally connected, perforce. For most of the population poverty dictated the choice of diet. A plentiful cosmopolitan cuisine reigned at court (Montanari 2014); it was garnished with rare and exotic ingredients indicating wealth, though also a background of culture deriving from greater familiarity with distant lands. -

The Traditions and Flavors of Roman Cuisine

Culinary Hosted Programs THE TRADITIONS AND FLAVORS OF ROMAN CUISINE 7 Days FROM $3,186 City life in Castel Gandolfo CULINARY HOSTED PROGRAM (6) Frascati PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS •Live like a local with a 6-night stay overlooking Rome in a town called Frascati, a summer stay favorite of the city’s nobility through the centuries •Savor the flavors of Rome with included meals in authentic Italian restaurants including the acclaimed, “Osteria di San Cesario” •Delve into the remains of ancient Tusculum, destroyed by the Roman Empire in 1191 LATIUM Ariccia Monte Porzio Catone •Learn the secrets of Roman cuisine by participating Rome Grottaferrata Frascati 6 in a cooking class lead by a renowned Frascati Nemi Castel Gandolfo culinary pro •Explore the two volcanic lake areas of Nemi and Albano – historic vacation spots of Caligula and Nero and home to the Pope’s summer residence •Visit the oldest historic winery in the region, learn ITALY how the wine is produced, and enjoy a tasting experience •Discover Slow Food Movement techniques visiting local farms that produce honey, herbs, and cheese, and sample these homegrown treats # - No. of overnight stays Arrangements by DAY 1 I ROME I FRASCATI Arrive in Rome and transfer to your hotel in Frascati. Just south of Rome, in the Alban Hills, lies a string of hill towns nestled among vineyards called “Castelli Romani” - “Roman Castles”. Frascati, a summer haunt for the Roman elite through the centuries, offers good food, fresh white wines and captivating views of Rome at a distance. This afternoon, get acquainted with this lovely town during a guided walking tour. -

Ebook Download the Story of Garum : Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted

THE STORY OF GARUM : FERMENTED FISH SAUCE AND SALTED FISH IN THE ANCIENT WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sally Grainger | 352 pages | 31 Dec 2020 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9781138284074 | English | London, United Kingdom The Story of Garum : Fermented Fish Sauce and Salted Fish in the Ancient World PDF Book Buying colatura this weekend. From published tituli picti in CIL, the majority of liquamen labels are on amphorae, while named and exclusive garum is largely found on the much smaller urceii. Strain through cheesecloth and cool. When a fish sauce substitute cannot be found, either salt or a mixture of salt and anchovy heated in olive oil, and then mashed up can suffice. Mix some dried aneth, anis, fennel seeds, laurel, black pepper and lovage and mix the resulting powder with nuoc mam. Older Stories. I actually prefer the taste of salt cod to fresh. Cite Share. Google or read the ingredients of a bottle and look for the word anchovy. In what follows I will offer a radically new way to approach the dilemma of how to differentiate between the various fish sauces which takes account of the opinions of those who made, traded and used these products. You can use either garum or nuoc mam in our recipe. Thanks for the suggestion. This poem and amphorae tituli picti suggest that mackerel actually served as the best fish to use both for muria and garum. Stir the pasta and sauce together until the spaghetti is evenly coated. And yes, the NOMA book is some serious fermenting homework. According to the agricultural book Geoponica , the garum referred to as Haimation was among the very best. -

The Ruin of the Roman Empire

7888888888889 u o u o u o u THE o u Ruin o u OF THE o u Roman o u o u EMPIRE o u o u o u o u jamesj . o’donnell o u o u o u o u o u o u o hjjjjjjjjjjjk This is Ann’s book contents Preface iv Overture 1 part i s theoderic’s world 1. Rome in 500: Looking Backward 47 2. The World That Might Have Been 107 part ii s justinian’s world 3. Being Justinian 177 4. Opportunities Lost 229 5. Wars Worse Than Civil 247 part iii s gregory’s world 6. Learning to Live Again 303 7. Constantinople Deflated: The Debris of Empire 342 8. The Last Consul 364 Epilogue 385 List of Roman Emperors 395 Notes 397 Further Reading 409 Credits and Permissions 411 Index 413 About the Author Other Books by James J. O’ Donnell Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher preface An American soldier posted in Anbar province during the twilight war over the remains of Saddam’s Mesopotamian kingdom might have been surprised to learn he was defending the westernmost frontiers of the an- cient Persian empire against raiders, smugglers, and worse coming from the eastern reaches of the ancient Roman empire. This painful recycling of history should make him—and us—want to know what unhealable wound, what recurrent pathology, what cause too deep for journalists and politicians to discern draws men and women to their deaths again and again in such a place. The history of Rome, as has often been true in the past, has much to teach us. -

Rome 2016 Program to SEND

A TASTE OF ANCIENT ROME 17–24 October 2016 Day-by-Day Program Elizabeth Bartman, archaeologist, and Maureen Fant, food writer, lead a unique, in-depth tour for sophisticated travelers who want to experience Rome through the eyes of two noted specialists with a passion for the city, its monuments, and its cuisine. Together they will introduce you to the fascinating archaeology of ancient foodways and to the fundamentals of modern Roman cuisine. Delicious meals, special tastings, and behind-the-scenes visits in Rome and its environs make this week-long land trip an exceptional experience. You’ll stay in the same hotel all week, in Rome’s historic center, with some out-of-town day trips. October is generally considered the absolutely best time to visit Rome. The sun is warm, the nights not yet cold, and the light worthy of a painting. The markets and restaurants are still offering the last of the summer vegetables—such as Rome’s particular variety of zucchini and fresh borlotti beans—as well as all the flavors of fall and winter in central Italy—chestnuts, artichokes, broccoli, broccoletti, chicory, wild mushrooms, stewed and roasted meats, freshwater fish, and so much more. Note: Logistics, pending permissions, and new discoveries may result in some changes to this itinerary, but rest assured, plan B will be no less interesting or delicious. B = Breakfast included L = Lunch included D = Dinner included S = Snack or tasting included MONDAY: WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION You’ll be met at Leonardo da Vinci Airport (FCO) or one of the Rome railroad stations and transferred to our hotel near the Pantheon, our base for the next seven nights.