Fish Sauces – the Food That Made Rome Great by Benedict Lowe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition-Tips-Low-Salt-Asian-Sauces

Nutrition Tips Alternatives to Salty Asian Sauces Asian cooking is often considered “healthy” because it Tips for reducing sodium in is usually lower in protein and higher in vegetables. But most Asian meals are typically made with sauces Asian sauces that can have large amounts of sodium. 1. Look for low sodium versions of Soy sauces, fish sauces, and sweet and sour sauces may your favorite brands at the local contain 900-1500 mg of sodium per tablespoon. This grocery store. These can often is 75-100% of what your daily intake should be; all in cut the sodium by half. one small spoon! 2. Try mixing the sauce with water When trying to follow a low sodium diet, it can be hard or other juices like pineapple to make your favorite Asian dishes without these salty juice to cut the sodium. sauces, but there are ways to reduce the salt and keep the flavor. 3. Use unseasoned rice vinegar to save even more sodium. Shop and compare a variety of brands. Traditional store bought sauces can be very high in sodium. 4. Instead of buying sauces, try making them at home so you Soy sauce: 920-1100mg per 1 tablespoon have control over how much salt Fish sauce: 1190-1500mg per 1 tablespoon is added. Sweet and Sour: 800 –1000 mg per 1 tablespoon 5. Look at hot chili sauce labels, many are low in sodium. Mixing your own sauces at home puts 6. Use sesame oil, chili oil and peanut oil to add Asian flavor to you in control of the meals without salty sauces. -

Michi's Ultimate Chicken Satay

Michi's Ultimate Chicken Satay Description The trick to this dish is to take your time. Make the marinade early so the flavors can develop. Don’t try to rush the sauce; it really needs to thicken slowly. Total time: 1 hr Yield: 4 Servings Ingredients 1 1/2 lb chicken tenderloin (substitute skinless chicken breast) 6 8" skewers fresh cilantro (for garnish) 2 Tbsp fish sauce 3 Tbsp light brown sugar 1 1/2 tsp Madras curry powder (or use what's in you pantry) 2 tsp garlic (minced) 1 pinch ground cumin 1 pinch salt 2 cup coconut milk 1 tsp green curry paste 1 tsp paprika 2 Tbsp creamy peanut butter 4 lime kafir leaves (substitute zest from one lime) 1/4 cup chopped roasted peanuts (unsalted, found in your Asian aisle as blanched peanuts) Prep Time: 1 hr Total Time: 1 hr Instructions Make the marinade ahead. Combine all marinade ingredients (1 teaspoon fish sauce,1 teaspoon light brown sugar, curry powder, 2 cloves minced garlic, ground cumin, salt, 3 tablespoons coconut milk) and let it sit for at least an hour. You can also soak your skewers at this time. Combine all the sauce ingredients (green curry paste, paprika, 2 teaspoons minced garlic, 2 tablespoons fish sauce, peanut butter, 3 tablespoons light brown sugar, 2 cups coconut milk, lime kafir leaves, chopped peanuts) in a medium pan and simmer gently until it reduces and becomes thick. Reserve ¼ cup of the sauce for brushing on the chicken during the cooking process. The chicken tenderloins need to be cut to half their original thickness. -

Summary of the Periodic Report on the State of Conservation, 2006

State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties in Europe SECTION II discovered, such as the Central Baths, the Suburban Baths, the College of the Priests of ITALY Augustus, the Palestra and the Theatre. The presence, in numerous houses, of furniture in carbonised wood due to the effects of the eruption Archaeological Areas of Pompei, is characteristic of Herculaneum. Hercolaneum and Torre The Villa of Poppea is preserved in exceptional way Annunziata and is one of the best examples of residential roman villa. The Villa of Cassius Tertius is one of Brief description the best examples of roman villa rustica. When Vesuvius erupted on 24 August A.D. 79, it As provided in ICOMOS evaluation engulfed the two flourishing Roman towns of Pompei and Herculaneum, as well as the many Qualities: Owing to their having been suddenly and wealthy villas in the area. These have been swiftly overwhelmed by debris from the eruption of progressively excavated and made accessible to Vesuvius in AD 79, the ruins of the two towns of the public since the mid-18th century. The vast Pompei and Herculaneum are unparalleled expanse of the commercial town of Pompei anywhere in the world for their completeness and contrasts with the smaller but better-preserved extent. They provide a vivid and comprehensive remains of the holiday resort of Herculaneum, while picture of Roman life at one precise moment in the superb wall paintings of the Villa Oplontis at time. Torre Annunziata give a vivid impression of the Recommendation: That this property be inscribed opulent lifestyle enjoyed by the wealthier citizens of on the World Heritage List on the basis of criteria the Early Roman Empire. -

1 Classics 270 Economic Life of Pompeii

CLASSICS 270 ECONOMIC LIFE OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM FALL, 2014 SOME USEFUL PUBLICATIONS Annuals: Cronache Pompeiane (1975-1979; volumes 1-5) (Gardner: volumes 1-5 DG70.P7 C7) Rivista di Studi Pompeiani (1987-present; volumes 1-23 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-3 DG70.P7 R585; CTP vols. 6-23 DG70.P7 R58) Cronache Ercolanesi: (1971-present; volumes 1-43 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1-19 PA3317 .C7) Vesuviana: An International Journal of Archaeological and Historical Studies on Pompeii and Herculaneum (2009 volume 1; others late) (Gardner: DG70.P7 V47 2009 V. 1) Notizie degli Scavi dell’Antichità (Gardner: beginning 1903, mostly in NRLF; viewable on line back to 1876 at: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000503523) Series: Quaderni di Studi Pompeiani (2007-present; volumes 1-6 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1, 5) Studi della Soprintendenza archeologica di Pompei (2001-present; volumes 1-32 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-32 (2012)] Bibliography: García y García, Laurentino. 1998. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei Monografie 14, 2 vol. (Rome). García y García, Laurentino. 2012. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Supplemento 1o (1999-2011) (Rome: Arbor Sapientiae). McIlwaine, I. 1988. Herculaneum: A guide to Printed Sources. (Naples: Bibliopolis). McIlwaine, I. 2009. Herculaneum: A guide to Sources, 1980-2007. (Naples: Bibliopolis). 1 Early documentation: Fiorelli, G. 1861-1865. Giornale degli scavi. 31 vols. Hathi Trust Digital Library: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009049482 Fiorelli, G. ed. 1860-1864. Pompeianarum antiquitatum historia. 3 vols. (Naples: Editore Prid. Non. Martias). Laidlaw, A. 2007. “Mining the early published sources: problems and pitfalls.” In Dobbins and Foss eds. pp. 620-636. Epigraphy: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 4 (instrumentum domesticum from Vesuvian sites), 10 (inscriptions from various regions, including Campania). -

Reasons to Stay a Little Bit Longer

CÆSAR AVGVSTVS ISOLA DI CAPRI REASONS TO STAY A LITTLE BIT LONGER ISLAND TOURS CAPRI AND Walking around the alleys, overlooking seaviews, appreciating the natural wonders of a island that has it all! ANACAPRI Accompanied by your own private guide, strolling around the historical city center of Anacapri and Capri visiting the pedestrian centers. TOUR ISLAND ROAD TOUR Since Roman times, the unparalleled natural beauty of Capri has captured the imagination of travelers. Sporty guests can enjoy exciting walks such as the Sentiero dei Fortini, explore the magnificent villas of Emperor Tiberius and visit the legendary Blue Grotto, made famous by Lord Byron. Our experienced guide will introduce clients to Capri’s hidden treasures on foot or by car. Duration: 4hrs PRIVATE Very close to the Vesuvius still remain ancient Roman ruins: Pompeii. In these archaeological sites you will have the unique occasion to walk through narrow streets once passed by old roman people, admire their houses EXCURSION beautifully decorated and understand the way they lived. The visit can be done with or without a guide (you can require a specific language for your TO POMPEI tour), we suggest to book a guided one to appreciate better this excursion. Duration: 8hrs Tour includes: • Hydrofoil roundtrip tickets to Sorrento • Private car from the port of Sorrento to Pompeii and back. • Tickets for the entrance of the ruins The prices do not include lunch PRIVATE Very close to the Vesuvius still remain ancient Roman ruins: Pompeii. In these archaeological sites you will have the unique occasion to walk through narrow streets once passed by old roman people, admire their houses EXCURSION beautifully decorated and understand the way they lived. -

Elenco Unificato Dei Giudici Popolari Di Primo Grado

Elenco unificato dei Giudici popolari di primo grado. ex Art.17 L.287/51. Comune di TORRE DEL GRECO N. COGNOME e NOME DATA NASCITA COMUNE NASCITA COMUNE RESIDENZA INDIRIZZO 1 ACAMPORA RAFFAELLA 21/04/1974 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA MONTEDORO, 97 2 ACCARDO CARLA 16/12/1962 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO CUPA OSPEDALE, 18/A 3 ACCARDO CAROLINA 20/07/1962 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO V.LE F. BALZANO, 16 4 ALLEGRETTO MARIA TERESA 24/03/1961 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA CIMAGLIA, 55 5 ARENIELLO IMMACOLATA 20/05/1959 NAPOLI TORRE DEL GRECO VIA PAGLIARELLE, 21/B 6 ASCIONE ANNA 08/04/1974 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA S.TERESA, 30 7 ASCIONE CARMEN 17/07/1974 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA NAZIONALE, 123/A 8 ASCIONE GIOVANNA 20/01/1976 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA A. DE GASPERI 79 9 ASCIONE GIUSEPPINA 07/05/1981 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA CIMAGLIA, 26 10 AVANO FRANCESCO 11/07/1964 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA S. GENNARIELLO, 21/B 11 BALZANO ROSA 02/01/1960 TORRE ANNUNZIATA TORRE DEL GRECO VIALE EUROPA, 56 12 BARLETTA ELISABETTA 09/04/1958 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA A. DE GASPERI, 62 13 BATTAGLIA GIOSUE' 06/03/1952 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA A. DE GASPERI, 15 14 BORRELLI FLORINDA 19/10/1974 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA MARTIRI D'AFRICA 10 15 BORRELLI MARIA TERESA 25/08/1952 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO VIA PROCIDA, 3 16 BORRIELLO MICHELE 10/03/1961 NAPOLI TORRE DEL GRECO VIA MARESCA, 28/A 17 BORRIELLO VINCENZO 04/05/1951 TORRE DEL GRECO TORRE DEL GRECO 2° VICO SAN -

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

The Thai Tabletop and Its Condiments Depending on the Dishes Offered

The Thai Tabletop and Its Condiments Depending on the dishes offered by a restaurant, there will be a specific selection of condiments available on the table. It's is a given that Thais customize their food before they eat it. Some of my Thai friends are heavy with the sugar shaker, some add a splash of Maggi or soy sauce, some prefer the sour heat of chiles and lime or vinegar, but it is with a dish of noodles that Thais really express themselves through their condiment selections. Every Thai has a personal ritual that they go through by adding these condiments in varying ratios to their noodles, and the noodle cook does not take offense in the slightest. In every noodle establishment, whether it is a full-blown restaurant, a shophouse café, a boat vendor, or a street vendor you will find khreuang puang : literally ‘circle of spices'. It's a reference to the standard condiments on the Thai table, especially where noodles are served: naam plaa (fish sauce), phrik pom (chile powder), phrik dong (chile slices in vinegar), and white sugar. The purpose of these condiments is to provide options for diners to modify their food as they wish, following the basic flavor profile of Thai cuisine: hot and sour, hot and salty, hot, and sweet (especially in the Central region). These four condiments are usually held in some sort of caddy, so that they can easily be passed around the table by diners. It's not unusual for them to be covered by a tightly-woven plastic mesh bowl turned upside-down, to exclude flying insects. -

Chicken Satay Satay Sauce

Chicken Satay Serves 4 1 cup unsweetened coconut milk 2 cloves garlic, minced 2 tablespoons finely chopped fresh cilantro 2 tablespoons fish sauce 2 teaspoons curry powder ¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper 12 ounces boneless, skinless chicken breasts Canola oil, for oiling grill Special Equipment: 10 to 12 6-inch bamboo skewers, soak the skewers in water for 30 minutes. 1. Make the marinade: Whisk the coconut milk, garlic, cilantro, fish sauce, curry powder, pepper in mixing bowl. 2. Pat the chicken breasts dry. Cut chicken into 3-inch long strips about 1 inch wide and ½ inch thick. 3. Combine the marinade and chicken, making sure the chicken is well coated. Allow the chicken to marinate for at least an hour or up to 8 hours inside the refrigerator. 4. Prepping before grilling: Thread the chicken strips onto the wooden skewers. Ensure that the chicken is positioned on the upper two thirds of the stick, from the tip to the middle. 5. Heat grill pan over high heat. Grill the skewers with the handles of the skewers sticking out of the sides - you can cover these with foil to prevent burning. (Alternatively, you can use the broiler). Grill until the chicken chars on some spots, turn, and grill on the other side until cooked through. Serve with the Satay Sauce. Satay Sauce Serves 4 1 cup unsweetened coconut milk 2 tablespoons light brown sugar 1 tablespoon tamarind concentrate 2 teaspoons Thai red curry paste 1 tablespoon fish sauce ¼ cup creamy peanut butter ¼ teaspoon paprika 3 cloves garlic, finely minced 3 tablespoons crushed roasted peanuts, for garnish 1. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

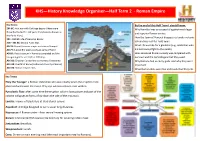

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Small-Scale Food Processing Enterprises in Malaysia

SMALL-SCALE FOOD PROCESSING ENTERPRISES IN MALAYSIA Ghani Senik Food Technology Research Station MARDI, 16800 Pasir Puteh Kelantan, Malaysia ABSTRACT Small-scale food enterprises have played a very important role in the Malaysian economy, particularly in terms of employment generation, better income distribution and as a training ground for entrepreneurs before they invest in larger enterprises. Small-scale food enterprises also have important linkages to related industries such as the manufacture of machinery, and food packaging materials, and suppliers of food ingredients. It is envisaged that small-scale food enterprises will continue to expand in line with policies and incentives introduced by the government. INTRODUCTION enterprise is one with net assets of US$200,001 - US$1.0 million. Food It is usual to discuss small- and processing companies are generally perceived medium-scale industries in Malaysia as a as agro-based industries which have a strong single group. There are an estimated 30,000 backward linkage. However this is not the such enterprises in Malaysia. A recent survey case in Malaysia, where it is estimated that conducted by the Ministry of International over 70% of the raw materials used in food Trade and Industry showed that they are of processing are imported (Ministry of four main types: processed foods (33%), wood International Trade and Industry 1993). This products, (24%), fabricated metal (15%) and is particularly true in the production of animal building materials (9%) (Malaysian Industrial feed and wheat-based products. Development Authority et al. 1985). These small and medium-sized industries play a very Profile of Small-Scale Food Processing important role in the Malaysian economy, especially in terms of generating employment.