200 Bc - Ad 400)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Death in Tyre: the Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria

University of Groningen Performing Death in Tyre de Jong, Lidewijde Published in: American Journal of Archaeology DOI: 10.3764/aja.114.4.597 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): de Jong, L. (2010). Performing Death in Tyre: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria. American Journal of Archaeology, 114(4), 597-630. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.4.597 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

The Rhetoric of Corruption in Late Antiquity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Rhetoric of Corruption in Late Antiquity A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics by Tim W. Watson June 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Michele R. Salzman, Chairperson Dr. Harold A. Drake Dr. Thomas N. Sizgorich Copyright by Tim W. Watson 2010 The Dissertation of Tim W. Watson is approved: ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In accordance with that filial piety so central to the epistolary persona of Q. Aurelius Symmachus, I would like to thank first and foremost my parents, Lee and Virginia Watson, without whom there would be quite literally nothing, followed closely by my grandmother, Virginia Galbraith, whose support both emotionally and financially has been invaluable. Within the academy, my greatest debt is naturally to my advisor, Michele Salzman, a doctissima patrona of infinite patience and firm guidance, to whom I came with the mind of a child and departed with the intellect of an adult. Hal Drake I owe for his kind words, his critical eye, and his welcome humor. In Tom Sizgorich I found a friend and colleague whose friendship did not diminish even after he assumed his additional role as mentor. Outside the field, I owe a special debt to Dale Kent, who ushered me through my beginning quarter of graduate school with great encouragement and first stirred my fascination with patronage. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude to the two organizations who have funded the years of my study, the Department of History at the University of California, Riverside and the Department of Classics at the University of California, Irvine. -

Persianism in Antiquity

Oriens et Occidens – Band 25 Franz Steiner Verlag Sonderdruck aus: Persianism in Antiquity Edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2017 CONTENTS Acknowledgments . 7 Rolf Strootman & Miguel John Versluys From Culture to Concept: The Reception and Appropriation of Persia in Antiquity . 9 Part I: Persianization, Persomania, Perserie . 33 Albert de Jong Being Iranian in Antiquity (at Home and Abroad) . 35 Margaret C. Miller Quoting ‘Persia’ in Athens . 49 Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones ‘Open Sesame!’ Orientalist Fantasy and the Persian Court in Greek Art 430–330 BCE . 69 Omar Coloru Once were Persians: The Perception of Pre-Islamic Monuments in Iran from the 16th to the 19th Century . 87 Judith A. Lerner Ancient Persianisms in Nineteenth-Century Iran: The Revival of Persepolitan Imagery under the Qajars . 107 David Engels Is there a “Persian High Culture”? Critical Reflections on the Place of Ancient Iran in Oswald Spengler’s Philosophy of History . 121 Part II: The Hellenistic World . 145 Damien Agut-Labordère Persianism through Persianization: The Case of Ptolemaic Egypt . 147 Sonja Plischke Persianism under the early Seleukid Kings? The Royal Title ‘Great King’ . 163 Rolf Strootman Imperial Persianism: Seleukids, Arsakids and Fratarakā . 177 6 Contents Matthew Canepa Rival Images of Iranian Kingship and Persian Identity in Post-Achaemenid Western Asia . 201 Charlotte Lerouge-Cohen Persianism in the Kingdom of Pontic Kappadokia . The Genealogical Claims of the Mithridatids . 223 Bruno Jacobs Tradition oder Fiktion? Die „persischen“ Elemente in den Ausstattungs- programmen Antiochos’ I . von Kommagene . 235 Benedikt Eckhardt Memories of Persian Rule: Constructing History and Ideology in Hasmonean Judea . -

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. -

A Study of the Levantine Agricultural Economy (1St-8Th C. AD)

Society and economy in marginal zones: a study of the Levantine agricultural economy (1st-8th c. AD) Andrea Zerbini Department of Classics and Philosophy Royal Holloway University of London PhD in Classics 1 2 Abstract This thesis analyses the social and economic structures that characterised settlement in ecologically marginal regions in the Roman to early-Arab Levant (1st-8th c. AD). Findings show that, far from being self-sufficient, the economy of marginal zones relied heavily on surplus production aimed at marketing. The connection of these regions to large-scale commercial networks is also confirmed by ceramic findings. The thesis is structured in four main parts. The first outlines the main debates and research trends in the study of ancient agrarian society and economy. Part II comprises a survey of the available evidence for settlement patterns in two marginal regions of the Roman Near East: the Golan Heights, the jebel al-cArab. It also includes a small- scale test study that concentrates on the long-term development of the hinterland of Sic, a hilltop village in the jebel al-cArab, which housed one of the most important regional sanctuaries in the pre-Roman and Roman period. Parts III and IV contain the core the thesis and concentrate on the Limestone Massif of northern Syria, a region located between the cities of Antioch, Aleppo (Beroia) and Apamea. Following settlement development from the 2nd c. BC to the 12 c. AD, these sections provide a comprehensive assessment of how a village society developed out of semi-nomadic groups (largely through endogenous transformations) and was able to attain great prosperity in Late Antiquity. -

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS the Ultimate Edition an Invaluable

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information CALENDRICAL CALCULATIONS The Ultimate Edition An invaluable resource for working programmers, as well as a fount of useful algorithmic tools for computer scientists, astronomers, and other calendar enthu- siasts, the Ultimate Edition updates and expands the previous edition to achieve more accurate results and present new calendar variants. The book now includes algorithmic descriptions of nearly forty calendars: the Gregorian, ISO, Icelandic, Egyptian, Armenian, Julian, Coptic, Ethiopic, Akan, Islamic (arithmetic and astro- nomical forms), Saudi Arabian, Persian (arithmetic and astronomical), Bahá’í (arithmetic and astronomical), French Revolutionary (arithmetic and astronomical), Babylonian, Hebrew (arithmetic and astronomical), Samaritan, Mayan (long count, haab, and tzolkin), Aztec (xihuitl and tonalpohualli), Balinese Pawukon, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Hindu (old arithmetic and medieval astronomical, both solar and lunisolar), and Tibetan Phug-lugs. It also includes information on major holidays and on different methods of keeping time. The necessary astronom- ical functions have been rewritten to produce more accurate results and to include calculations of moonrise and moonset. The authors frame the calendars of the world in a completely algorithmic form, allowing easy conversion among these calendars and the determination of secular and religious holidays. Lisp code for all the algorithms is available in machine- readable form. Edward M. Reingold is Professor of Computer Science at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Nachum Dershowitz is Professor of Computational Logic and Chair of Computer Science at Tel Aviv University. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05762-3 — Calendrical Calculations 4th Edition Frontmatter More Information About the Authors Edward M. -

Atlas of the Ornamental and Building Stones of Volubilis Ancient Site (Morocco) Final Report

Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco) Final report BRGM/RP-55539-FR July, 2008 Study carried out in the framework of MEDISTONE project (European Commission supported research program FP6-2003- INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n°15245) D. Dessandier With the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas Checked by: Approved by: Name: Jean FERAUD Name: Marc AUDIBERT Date: 03 September 2008 Date: 19 September 2008 If the present report has not been signed in its digital form, a signed original of this document will be available at the information and documentation Unit (STI). BRGM’s quality management system is certified ISO 9001:2000 by AFAQ. IM 003 ANG – April 05 Keywords: Morocco, Volubilis, ancient site, ornamental stones, building stones, identification, provenance, quarries. In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows: D. Dessandier with the collaboration (in alphabetical order) of F. Antonelli, R. Bouzidi, M. El Rhoddani, S. Kamel, L. Lazzarini, L. Leroux and M. Varti-Matarangas (2008) – Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis ancient site (Morocco). BRGM/RP-55539-FR, 166 p., 135 fig., 28 tab., 3 app. © BRGM, 2008. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM. Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis Synopsis The present study titled “Atlas of the ornamental and building stones of Volubilis” was performed in the framework of the project MEDISTONE (“Preservation of ancient MEDIterranean sites in terms of their ornamental and building STONE: from determining stone provenance to proposing conservation/restoration techniques”) supported by the European Commission (research program FP6-2003-INCO-MPC-2 / Contract n° 015245). -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Romans Had So Many Gods

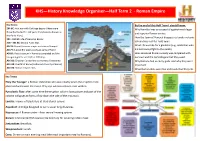

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

Roman Roads of Britain

Roman Roads of Britain A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 04 Jul 2013 02:32:02 UTC Contents Articles Roman roads in Britain 1 Ackling Dyke 9 Akeman Street 10 Cade's Road 11 Dere Street 13 Devil's Causeway 17 Ermin Street 20 Ermine Street 21 Fen Causeway 23 Fosse Way 24 Icknield Street 27 King Street (Roman road) 33 Military Way (Hadrian's Wall) 36 Peddars Way 37 Portway 39 Pye Road 40 Stane Street (Chichester) 41 Stane Street (Colchester) 46 Stanegate 48 Watling Street 51 Via Devana 56 Wade's Causeway 57 References Article Sources and Contributors 59 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 61 Article Licenses License 63 Roman roads in Britain 1 Roman roads in Britain Roman roads, together with Roman aqueducts and the vast standing Roman army, constituted the three most impressive features of the Roman Empire. In Britain, as in their other provinces, the Romans constructed a comprehensive network of paved trunk roads (i.e. surfaced highways) during their nearly four centuries of occupation (43 - 410 AD). This article focuses on the ca. 2,000 mi (3,200 km) of Roman roads in Britain shown on the Ordnance Survey's Map of Roman Britain.[1] This contains the most accurate and up-to-date layout of certain and probable routes that is readily available to the general public. The pre-Roman Britons used mostly unpaved trackways for their communications, including very ancient ones running along elevated ridges of hills, such as the South Downs Way, now a public long-distance footpath.