The Six Seasons of the Woodland Cree: a Lesson to Support Science 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of FNCFS Agencies in Saskatchewan

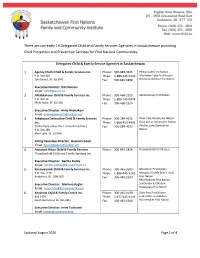

There are currently 19 Delegated Child and Family Services Agencies in Saskatchewan providing Child Protection and Prevention Services for First Nations Communities. Delegated Child & Family Service Agencies in Saskatchewan 1 Agency Chiefs Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-883-3345 Pelican Lake First Nation P.O. Box 329 TFree: 1-888-225-2244 Witchekan Lake First Nation Spiritwood, SK S0J 2M0 Fax: 306-883-3838 Whitecap Dakota First Nation Executive Director: Rick Dumais Email: [email protected] 2 Ahtahkakoop Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-468-2520 Ahtahkakoop First Nation P.O. Box 10 TFree: 1-888-745-0478 Mont Nebo, SK S0J 1X0 Fax: 306-468-2524 Executive Director: Anita Ahenakew Email: [email protected] 3 Athabasca Denesuline Child & Family Services Phone: 306-284-4915 Black Lake Denesuline Nation Inc. TFree: 1-888-439-4995 Fond du Lac Denesuline Nation (Yuthe Dene Sekwi Chu L A Koe Betsedi Inc.) Fax: 306-284-4933 Hatchet Lake Denesuline Nation P.O. Box 189 Black Lake, SK S0J 0H0 Acting Executive Director: Rosanna Good Email: Rgood@[email protected] 4 Awasisak Nikan Child & Family Services Phone: 306-845-1426 Thunderchild First Nation Thunderchild Child and Family Services Inc. Executive Director: Bertha Paddy Email: [email protected] 5 Kanaweyimik Child & Family Services Inc. Phone: 306-445-3500 Moosomin First Nation P.O. Box 1270 TFree: 1-888-445-5262 Mosquito Grizzly Bear’s Head Battleford, SK S0M 0E0 Fax: 306-445-2533 First Nation Red Pheasant First Nation Executive Director: Marlene Bugler Saulteaux First Nation Email: [email protected] Sweetgrass First Nation 6 Keyanow Child & Family Centre Inc. -

OTC October Newsletter Final Draft

The Office of the Treaty Commissioner (OTC) is mandated to advance the Treaty goal of establishing good relations among all people of Saskatchewan. The Office of the Treaty Commissioner continues to work with First Nation’s, provincial school systems, and other educational institutions to raise the awareness and understanding of Treaties and First Nations People Quarterly Newsletter Also available on our website at Volume 1 Issue 3 www.otc.ca October 2014 Annual Livelihood – Livelihood – OTC OTC All Nations Woodland Challenges in Saskatchewan First Education Speakers Traditional st Nations Economic Family & Youth Cree Gathering the 21 Century Development Bureau Network Gathering By: George E. Lafond By: Milton Tootoosis By: April Roberts By: Brenda Ahenekew By: Jennifer Heimbecker By: Robin Bendig This year’s theme for There is an urgency Participants also The community of “The people of The “Gathering” the Woodland Cree to defining what learned about Stanley Mission Saskatoon, you focused on Gathering was, “pimâcihisowin” ‘branding’ and hosts a spectacular walked with us when preserving and “Strengthening means as we move communicating their three day event the load was heavy, strengthening First Unity, Celebrating forward in the new communities; called the River and for that we will Nations culture, Culture, Promoting age business planning; Gathering. The always cherish you,” traditions and Community and and financial literacy Gathering is held identity by offering Recognizing next to the oldest various ceremonies History.” Church in and workshops. Saskatchewan 3-4 5 6 7 8 9 DID YOU KNOW? Reconciliation with our sister The OTC welcomes Rhett Sangster as Director of province - OTC commends the Reconciliation and Community Partnerships. -

Wollaston Road

WOLLASTON LAKE ROAD ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Biophysical Environment 4.0 Biophysical Environment 4.1 INTRODUCTION This section provides a description of the biophysical characteristics of the study region. Topics include climate, geology, terrestrial ecology, groundwater, surface water and aquatic ecology. These topics are discussed at a regional scale, with some topics being more focused on the road corridor area (i.e., the two route options). Information included in this section was obtained in full or part from direct field observations as well as from reports, files, publications, and/or personal communications from the following sources: Saskatchewan Research Council Canadian Wildlife Service Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board Reports Saskatchewan Museum of Natural History W.P. Fraser Herbarium Saskatchewan Environment Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre Environment Canada Private Sector (Consultants) Miscellaneous publications 4.2 PHYSIOGRAPHY Both proposed routes straddle two different ecozones. The southern portion is located in the Wollaston Lake Plain landscape area within the Churchill River Upland ecoregion of the Boreal Shield ecozone. The northern portion is located in the Nueltin Lake Plain landscape area within the Selwyn Lake Upland ecoregion of the Taiga Shield ecozone (Figure 4.1). (SKCDC, 2002a; Acton et al., 1998; Canadian Biodiversity, 2004; MDH, 2004). Wollaston Lake lies on the Precambrian Shield in northern Saskatchewan and drains through two outlets. The primary Wollaston Lake discharge is within the Hudson Bay Drainage Basin, which drains through the Cochrane River, Reindeer Lake and into the Churchill River system which ultimately drains into Hudson Bay. The other drainage discharge is via the Fond du Lac River to Lake Athabasca, and thence to the Arctic Ocean. -

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview

Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Faculty of Humanities, Department of Linguistics and Faculty of Education, Indigenous Education Art Napoleon, 2014 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Key Terms and Concepts for Exploring Nîhiyaw Tâpisinowin the Cree Worldview by Art Napoleon Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental Member iii ABstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Leslie Saxon, Department of Linguistics Supervisor Dr. Peter Jacob, Department of Linguistics Departmental MemBer Through a review of literature and a qualitative inquiry of Cree language practitioners and knowledge keepers, this study explores traditional concepts related to Cree worldview specifically through the lens of nîhiyawîwin, the Cree language. Avoiding standard dictionary approaches to translations, it provides inside views and perspectives to provide broader translations of key terms related to Cree values and principles, Cree philosophy, Cree cosmology, Cree spirituality, and Cree ceremonialism. It argues the importance of providing connotative, denotative, implied meanings and etymology of key terms to broaden the understanding of nîhiyaw tâpisinowin and the need -

Written Submission from the Lac La Ronge Indian Band Mémoire De

CMD 21-H2.12 File / dossier : 6.01.07 Date: 2021-03-17 Edocs: 6515664 Written submission from the Mémoire de Lac La Ronge Indian Band Lac La Ronge Indian Band In the Matter of the À l’égard de Cameco Corporation, Cameco Corporation, Cigar Lake Operation établissement de Cigar Lake Application for the renewal of Cameco’s Demande de renouvellement du permis de mine uranium mine licence for the Cigar Lake d’uranium de Cameco pour l’établissement de Operation Cigar Lake Commission Public Hearing Audience publique de la Commission April 28-29, 2021 28 et 29 avril 2021 This page was intentionally Cette page a été intentionnellement left blank laissée en blanc ADMINISTRATION BOX 480, LA RONGE SASK. S0J 1L0 Lac La Ronge PHONE: (306) 425-2183 FAX: (306) 425-5559 1-800-567-7736 Indian Band March 16, 2021 Senior Tribunal Officer, Secretariat Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission 280 Slater St. Ottawa ON Email: [email protected] Re: Intervention letter on renewal application for Cameco’s uranium mine license for the Cigar Lake Operation Thank you for the opportunity to submit this intervention letter on behalf of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band (LLRIB). The LLRIB is the largest First Nation in Saskatchewan, and one of the largest in Canada with over 11,408 band members. The LLRIB lands, 19 reserves in total, extend from farmlands in central Saskatchewan all the way north through the boreal forest to the Churchill River and beyond. We are a Woodland Cree First Nation, members of the Prince Albert Grand Council and we pride ourselves on a commitment to education opportunities, business successes, and improving the well-being of our band members. -

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-Making in the NWT

Understanding Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the Northwest Territories: Chapter 2: Early Treaty-making in the NWT he first chapter in this series, Understanding Aboriginal The Royal Proclamation Tand Treaty Rights in the NWT: An Introduction, touched After Great Britain defeated France for control of North briefly on Aboriginal and treaty rights in the NWT. This America, the British understood the importance of chapter looks at the first contact between Aboriginal maintaining peace and good relations with Aboriginal peoples and Europeans. The events relating to this initial peoples. That meant setting out rules about land use contact ultimately shaped early treaty-making in the NWT. and Aboriginal rights. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 Early Contact is the most important statement of British policy towards Aboriginal peoples in North America. The Royal When European explorers set foot in North America Proclamation called for friendly relations with Aboriginal they claimed the land for the European colonial powers peoples and noted that “great frauds and abuses” had they represented. This amounted to European countries occurred in land dealings. The Royal Proclamation also asserting sovereignty over North America. But, in practice, said that only the Crown could legally buy Aboriginal their power was built up over time by settlement, trade, land and any sale had to be made at a “public meeting or warfare, and diplomacy. Diplomacy in these days included assembly of the said Indians to be held for that purpose.” entering into treaties with the indigenous Aboriginal peoples of what would become Canada. Some of the early treaty documents aimed for “peace and friendship” and refer to Aboriginal peoples as “allies” rather than “subjects”, which suggests that these treaties could be interpreted as nation-to-nation agreements. -

The Rose Collection of Moccasins in the Canadian Museum of Civilization : Transitional Woodland/Grassl and Footwear

THE ROSE COLLECTION OF MOCCASINS IN THE CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION : TRANSITIONAL WOODLAND/GRASSL AND FOOTWEAR David Sager 3636 Denburn Place Mississauga, Ontario Canada, L4X 2R2 Abstract/Resume Many specialists assign the attribution of "Plains Cree" or "Plains Ojibway" to material culture from parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In fact, only a small part of this area was Grasslands. Several bands of Cree and Ojibway (Saulteaux) became permanent residents of the Grasslands bor- ders when Reserves were established in the 19th century. They rapidly absorbed aspects of Plains material culture, a process started earlier farther west. This paper examines one such case as revealed by footwear. Beaucoup de spécialistes attribuent aux Plains Cree ou aux Plains Ojibway des objets matériels de culture des régions du Manitoba ou de la Saskatch- ewan. En fait, il n'y a qu'une petite partie de cette région ait été prairie. Plusieurs bandes de Cree et d'Ojibway (Saulteaux) sont devenus habitants permanents des limites de la prairie quand les réserves ont été établies au XIXe siècle. Ils ont rapidement absorbé des aspects de la culture matérielle des prairies, un processus qu'on a commencé plus tôt plus loin à l'ouest. Cet article examine un tel cas comme il est révélé par des chaussures. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XIV, 2(1 994):273-304. 274 David Sager The Rose Moccasin Collection: Problems in Attribution This paper focuses on a unique group of eight pair of moccasins from southern Saskatchewan made in the mid 1880s. They were collected by Robert Jeans Rose between 1883 and 1887. -

Indigenous Languages

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES PRE-TEACH/PRE-ACTIVITY Have students look at the Indigenous languages and/or language groups that are displayed on the map. Discuss where this data came from (the 2016 census) and what biases or problems this data may have, such as the fear of self-identifying based on historical reasons or current gaps in data. Take some time to look at how censuses are performed, who participates in them, and what they can learn from the data that is and is not collected. Refer to the online and poster map of Indigenous Languages in Canada featured in the 2017 November/December issue of Canadian Geographic, and explore how students feel about the number of speakers each language has and what the current data means for the people who speak each language. Additionally, look at the language families listed and the names of each language used by the federal government in collecting this data. Discuss with students why these may not be the correct names and how they can help in the reconciliation process by using the correct language names. LEARNING OUTCOMES: • Students will learn about the number and • Students will learn about the importance of diversity of languages and language groups language and the ties it has to culture. spoken by Indigenous Peoples in Canada. • Students will become engaged in learning a • Students will learn that Indigenous Peoples local Indigenous language. in Canada speak many languages and that some languages are endangered. INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES Foundational knowledge and perspectives FIRST NATIONS “One of the first acts of colonization and settlement “Our languages are central to our ceremonies, our rela- is to name the newly ‘discovered’ land in the lan- tionships to our lands, the animals, to each other, our guage of the colonizers or the ‘discoverers.’ This is understandings, of our worlds, including the natural done despite the fact that there are already names world, our stories and our laws.” for these places that were given by the original in- habitants. -

Ridington-Dane-Zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project

Contract Position Description December 10, 2020 Position Title Archival Assistant – Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive Repatriation Project Project Background The Ridington-Dane-zaa Digital Archive (RDA) project is a collaborative digital repatriation initiative between: • The Ridington family ethnographers and their Dane-zaa heritage collection(s)i, • The Dane-zaa (Dene peoples indigenous to the Peace River region) communities whose culture is documented by the Ridington Collection: o Blueberry River First Nation o Doig River First Nation o Halfway River First Nation o Prophet River First Nation • University & industry partners including: o UBC CEDaR Lab as interim platform/portal host and steward o BC Hydro as community archive capacity development funder o Nation Governance Initiative, grant issued to Doig River First Nation by New Relationship Trust to help define Athabaskan / Dane-zaa specific protocols for stewardship including access, use, attribution and sharing (2020-2021) https://www.newrelationshiptrust.ca/funding/nation-governance/ o (potentially) UNBC as interim archival storage for physical master materials. Place for final storage to be determined. Options being explored at this time include: § Tse Kwą̂ Heritage Centre at Charlie Lake, BC § Dene Heritage Centre (in proposal/development stage for Indigenous communities of the Peace River Region) Goal The goal of this project is to digitally archive and catalog the entire Ridington collection so that it can be returned (repatriated) to communities for their use and stewardship. Ridington-Dane-zaa Collection History The Ridington Collection of Dane-zaa audio recordings, images, video recordings, and texts began in 1964 after Robin Ridington and Antonia Mills (Antonia Ridington at the time) had met at Harvard University in 1963 as students, married, and began their field work with the Dane-zaa. -

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background

La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Background Document La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan Management Plan La Ronge Integrated Land Use Management Plan, January 2003 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE# Lists of Tables and Figures................................................................................... ii Chapter 1 - The La Ronge Planning Area........................................................... 1 Chapter 2 - Ecological and Natural Resource Description............................... 4 2.1 Landscape Area Description..................................................... 4 2.1.1 Sisipuk Plain Landscape Area................................... 4 2.1.2 La Ronge Lowland Landscape Area.......................... 4 2.2 Forest Resources..................................................................... 4 2.3 Water Resources..................................................................... 5 2.4 Geology.................................................................................... 5 2.5 Wildlife Resources.................................................................... 6 2.6 Fish Resources......................................................................... 9 Chapter 3 - Existing Resource Uses and Values................................................11 3.1 Timber......................................................................................12 3.2 Non-Timber Forest Products......................................................13 -

The Archaeology of Brabant Lake

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF BRABANT LAKE A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Sandra Pearl Pentney Fall 2002 © Copyright Sandra Pearl Pentney All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, In their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5B 1) ABSTRACT Boreal forest archaeology is costly and difficult because of rugged terrain, the remote nature of much of the boreal areas, and the large expanses of muskeg. -

LANGUAGES of the LAND a RESOURCE MANUAL for ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS

LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS Prepared by: Crosscurrent Associates, Hay River Prepared for: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Remarks - NWT Literacy Council . 2 Definitions . 3 Using the Manual . 4 Statements by Aboriginal Language Activists . 5 Things You Need to Know . 9 The Importance of Language . 9 Language Shift. 10 Community Mobilization . 11 Language Assessment. 11 The Status of Aboriginal Languages in the NWT. 13 Chipewyan . 14 Cree . 15 Dogrib . 16 Gwich'in. 17 Inuvialuktun . 18 South Slavey . 19 North Slavey . 20 Aboriginal Language Rights . 21 Taking Action . 23 An Overview of Aboriginal Language Strategies . 23 A Four-Step Approach to Language Retention . 28 Forming a Core Group . 29 Strategic Planning. 30 Setting Realistic Language Goals . 30 Strategic Approaches . 31 Strategic Planning Steps and Questions. 34 Building Community Support and Alliances . 36 Overcoming Common Language Myths . 37 Managing and Coordinating Language Activities . 40 Aboriginal Language Resources . 41 Funding . 41 Language Resources / Agencies . 43 Bibliography . 48 NWT Literacy Council Languages of the Land 1 LANGUAGES of THE LAND A RESOURCE MANUAL FOR ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE ACTIVISTS We gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance received from the Government of the Northwest Territories, Department of Education, Culture and Employment Copyright: NWT Literacy Council, Yellowknife, 1999 Although this manual is copyrighted by the NWT Literacy Council, non-profit organizations have permission to use it for language retention and revitalization purposes. Office of the Languages Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Cover Photo: Ingrid Kritch, Gwich’in Social and Cultural Institute INTRODUCTORY REMARKS - NWT LITERACY COUNCIL The NWT Literacy Council is a territorial-wide organization that supports and promotes literacy in all official languages of the NWT.