Words About Memories but Not Exactly: on Leung Chi Wo's Artistic Practice1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development 02 OverviewOOvveveerrvieeww 04 ExistingEExExixisxixisssttitinng CConditionsonondddiittioonnsns 07 OpportunitiesOOppppppoortunnittiiieeses & CoCConstraintsoonnssstttrraaiainntnntss 08 OverallOOvveveerall PPlanninglananniiinnngg ApAApproachespppprrooaoacaachchchehhesess 16 OverallOOvveeraall PPlPlanninglalaannnnnniiinnngg & DesignDDeesessign FrameworkFrarammeeewwoworrkk 20 BroadBBrBroroooaadd LandLaLandnd UUsUseses CoCConceptsoonnccecepeptptss 28 NextNNeexexxt StepStStept p Overview Background 1.4 The Study adopts a comprehensive and integrated approach to formulate the optimal scale of development 1.1 According to the latest population projection, Hong in the NTN. It has explored the potential of building new Kong’s population would continue to grow, from 7.24 communities and vibrant employment and business million in 2014 to 8.22 million by 2043. There is a nodes in the area to contribute to the long-term social continuous demand for land for economic development and economic development of Hong Kong. to sustain our competitiveness. There are also increasing community aspirations for a better living environment. 1.5 The Study is a preliminary feasibility study which has examined the baseline conditions of the NTN covering 1.2 To maintain a steady land supply, the Government is about 5,300 hectares (ha) of land (Plan 1) to identify looking into various initiatives, including exploring further potential development areas (PDAs) and formulate an development opportunities in the -

Intermediates1#1 Gettingajobinhongkong

LESSON NOTES Intermediate S1 #1 Getting a Job in Hong Kong CONTENTS 2 Traditional Chinese 2 Jyutping 3 English 3 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 6 Vocabulary Phrase Usage 6 Grammar 7 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TRADITIONAL CHINESE 1. A: 2. B: 3. A: 4. B: 5. A: 6. B: 7. A: "" 8. B: JYUTPING 1. A: ze3 man6 seng1, ni1 dou6 hai6 mai6 ceng2 jan4 aa3 ? 2. B: hai6, nei5 soeng2 gin3 bin1 fan6 gung1 ? 3. A: ngo5 hai6 lei4 jing3 ping3 coi4 mou3 ging1 lei5 ge3. 4. B: hai2 ni1 hong4 zou6 zo2 gei2 noi6 ? 5. A: ngo5 aam1 aam1 bat1 jip6, zung6 bin1 zou6 bin1 hok6. 6. B: gam2 nei5 gok3 dak1 zi6 gei2 jau5 me1 jau1 sai3 ? CONT'D OVER CANTONES ECLAS S 101.COM INTERMEDIATE S1 #1 - GETTING A JOB IN HONG KONG 2 7. A: ngo5 hai2 sei3 daai6 sat6 zaap6 zo2 bun3 nin4, jau5 wui6 gai3 si1 paai4. 8. B: hou2, min6 si5 git3 gwo2 ngo5 dei6 wui5 jau5 zyun1 jan4 tung1 zi1 nei5. ENGLISH 1. A: Excuse me, is the company looking for employees? 2. B: Yes, what kind of position are you looking for? 3. A: I'm here for the financial manager position. 4. B: How long have you been working in this field? 5. A: I've just graduated. I'm looking for work while I learn more. 6. B: So, why do you think you're a good hire? 7. A: I've been an intern with one of the Top Four accounting companies for half a year, and I've got an accounting certificate. -

Legislative Council Panel on Transport Subcommittee on Matters Relating to Railways Retrofitting of Automatic Platform Gates On

LC Paper No. CB(1)1072/10-11(02) Legislative Council Panel on Transport Subcommittee on Matters Relating to Railways Retrofitting of Automatic Platform Gates on the East Rail Line Purpose This paper aims to present the results and conclusions of the technical studies regarding the retrofitting of automatic platform gates (APGs) on the East Rail Line (EAL). Background 2. All MTR train platforms have been designed and built to international standards. Supplemented with additional safety warning devices and measures as well as regular educational activities on platform safety, a safe travelling environment is provided for MTR passengers. 3. While international standards do not require APGs for safe railway operations and APGs are not installed in most of the world’s railways, voices in the Hong Kong community have, for a variety of reasons, requested APGs to be retrofitted in the MTR platforms that currently do not have them. 4. Work is now in progress to install APGs at eight at-grade and above-ground stations on the Kwun Tong, Tsuen Wan and Island Lines. 5. Regarding the retrofitting of APGs at EAL stations, technical studies have been conducted with a view to identifying feasible solutions. However, the studies reveal that retrofitting of APGs at EAL stations poses particularly difficult challenges. They include - (a) safety risk associated with wide platform gaps; (b) limitations of existing signalling system; (c) limitations of existing trains; and (d) limitations of platform structures. 1 Safety risk associated with wide platform gaps and the trial of mechanical gap fillers 6. Platform gaps are required in safe train operations to prevent trains in motion from hitting the platform when arriving and departing a station. -

Fanling North New Development Areas

¦Ë Chuk Yuen WONG MAU HANG SHAN º¯Âo¦Ã¤ Leachate R ¬û E Treatment Works V KONG YIU I R N »ÉÆ E °ï¶ H TUNG LO Z Landfill N ĵ HANG E H Police Post S ªF ©ù ¸û¼ TUNG FUNG NGONG TONG Kaw Liu AU Village ¦ ¤ì´ò ² ` ĵ Às§ °t¤ ĵ Muk Wu Police Post LUNG MEI ©â¤ Ser Res PoliceNga Yiu Post LEGEND: Pumping ¥´¹ª ²À TENG ( NES P Station AG ¥ËŽ Ta Kwu LingKan Village Tau Wai G I ER) ¥Û¹ ¤ì N RIV R G Nga Yiu Ha Muk Wu VE YUEN SHEK TSAI HA RI ĵ ¦Ñ¹ Police ¤åÀ LO SHUE LING ¥ ¥´¹ Post MAN KAM TO TA KWU LING ¤ô¤ ¶í SHUI NGAU TSO Tong Fong »ñ° ¥Û ¥Ý® Fung Wong Wu SHEK O Wo Keng Shan ¶g¥ ĵ Police Post ©W Chow Tin Tsuen Ping Yeung «n §õ ¤ô NAM HANG ·s« T Lei Uk Ä®´ San Uk Ling ¸ Shui Hau HOO HOK WAI Ò ¶êÀ ¹ A ä ¤j¨ YUEN LENG R à BOUNDARY OF KWU TUNG NORTH CHAI À I ĵ TA SHA LOK V ª@¥ å E Police P R 183 Post ¤ I Sing Ping Village G N N A G G E S Sandy Ridge Cemetery H ¨FÀ• ( C P E E I G N D I G Cheung Shan Monastery F R Y Y O ¨ RA D U D ÂùÉÓ N D E ±o¤ ù N ®Æ A LECKY PASS A O R Tak Yuet LauL Lo Wu NEW DEVELOPMENT AREA à S R I Liu Pok ( SEUNG MA o ¥´¹ªÀ ®£À V LEI YUE ) ĵ ¹ ¬û¥ E Ta Kwu Ling Farm O KONG NGA PO HUNG LUNG R Police W T ) © Post u ĵ ± HANG ¤j® Police M W A ù ï Tai Po Tin ªø Post K à ¥ CHEUNG SHAN LO WU ® N ¤ô¬ A ¿ß M ¨F ª ©W Shui Lau Hang TENTATIVE SEWAGE STAG HILL e Sha Ling R Ping Che n ¥Û I ĵ i Police Post SHEK MA V l E e R p ©Wà| «H¸q l i Ping Che ¤j¥ ô ne P Lutheran ¤ un I New Village é T N CREST HILL ¿ É New Village r D( °t¤ ( TAI SHEK MO ) te UN ¾ ¤û¨ SG Ser Res °t¤ Wa ¤W¤s HORN HILL ĵ Ser Res Police Sheung Shan ( NGAU KOK SHAN ) T ¹v U Post ®à(ªø¨j Firing Range Kai Wat N ¤U¤s ¥ÕÅ ±Òª ÅÂÀ G TABLE HILL Kai Fong ¾î¤s¸ R PAK HOK ¸¨°¨¬wª ( CHEUNG PO TAU ) Ha Shan Tse Koo °¨¯óà I Garden Wang Shan Keuk µÚ V §ü Kai Wat SHAN LOK MA CHAU LOOP Hang Ma Tso Lung E San Tsuen Ngam Pin R CHAM SHAN ¤j¬ San Tsuen ) ù´ò¤À TAI HOM TUK PUMPING STATION Lo Wu Classification Range 183 °¨¯ ±ÆÀ ¬õ¾ô MA yTSO LUNG r e VERNON PASS Hung Kiu n ©W a i Âo¤ l d ( PAI TAU LO ) e ¥Õ¥Ð San Tsuen p PING HANG n Water Treatment i u a P Pak Tin Works ªê¦ PWP ITEM NO. -

Shenzhen-Hong Kong Borderland

FORUM Transformation of Shen Kong Borderlands Edited by Mary Ann O’DONNELL Jonathan BACH Denise Y. HO Hong Kong view from Ma Tso Lung. PC: Johnsl. Transformation of Shen Kong Borderlands Mary Ann O’DONNELL Jonathan BACH Denise Y. HO n August 1980, the Shenzhen Special and transform everyday life. In political Economic Zone (SEZ) was formally documents, newspaper articles, and the Iestablished, along with SEZs in Zhuhai, names of businesses, Shenzhen–Hong Kong is Shantou, and Xiamen. China’s fifth SEZ, Hainan shortened to ‘Shen Kong’ (深港), suturing the Island, was designated in 1988. Yet, in 2020, cities together as specific, yet diverse, socio- the only SEZ to receive national attention on technical formations built on complex legacies its fortieth anniversary was Shenzhen. Indeed, of colonial occupation and Cold War flare-ups, General Secretary Xi Jinping attended the checkpoints and boundaries, quasi-legal business celebration, reminding the city, the country, opportunities, and cross-border peregrinations. and the world not only of Shenzhen’s pioneering The following essays show how, set against its contributions to building Socialism with Chinese changing cultural meanings and sifting of social Characteristics, but also that the ‘construction orders, the border is continuously redeployed of the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater and exported as a mobile imaginary while it is Bay Area is a major national development experienced as an everyday materiality. Taken strategy, and Shenzhen is an important engine together, the articles compel us to consider how for the construction of the Greater Bay Area’ (Xi borders and border protocols have been critical 2020). Against this larger background, many to Shenzhen’s success over the past four decades. -

Cross-Border Education for Pupils of Kindergartens and Schools: the Case of Hong Kong

The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives Vol. 17, No. 3, 2018, pp. 93-107 https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ Cross-border education for pupils of kindergartens and schools: The case of Hong Kong Philip Wing Keung Chan Faculty of Education, Monash University, Australia: [email protected] Cross-border education is defined as the movement of people, knowledge, programs, providers, and curriculums across national or regional jurisdictional borders. Each year, millions of students access better education by crossing their national borders from less developed or newly-industrialized countries to Western, industrialised countries. Most are tertiary education students but the numbers engaged in secondary, primary, and pre-school education are also significant. Under the implementation of “one country two systems” in Hong Kong after the transition of sovereignty from Britain to China in 1997, and a decision of a case in The Court of Final Appeal of Hong Kong in 2011, babies born in Hong Kong to mainland Chinese parents are entitled to the right of abode in Hong Kong. Since then, tens of thousands of such births have occurred. More than 20,000 cross-border students travel from China to attend public schools in Hong Kong every day. This paper explores equality issues faced by these students. The paper evaluates the results of various stakeholders working together to solve important issues; for example, dedicated school zones, immigration clearance services, setting up Hong Kong classes in Chinese schools, and language, communication, and cultural support. The paper argues that inequality is prevalent. Keywords: Cross-border education; educational equality; school education INTRODUCTION International and cross-border student mobility is not a new phenomenon. -

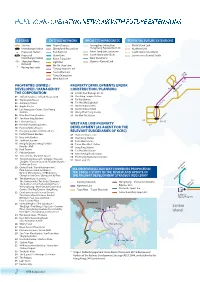

2 Hong Kong Operating Network with Future

Shenzhen Lo Wu HONG KONG OPERATING NETWORK WITH FUTURE EXTENSIONS Intercity Through Beijing Train Route Map Lok Ma Chau Sheung Shui LEGEND EXISTING NETWORK PROJECTS IN PROGRESS POTENTIAL FUTURE EXTENSIONS Shanghai Station Airport Express Guangzhou-Shenzhen- North Island Link Kwu Tung Hong Kong Express Rail Link Fanling Beijing Line Interchange Station Disneyland Resort Line Northern Link Zhaoqing Guangzhou Proposed Station East Rail Line Kwun Tong Line Extension South Island Line (West) Shanghai Line South Island Line (East) Proposed Island Line Extension to Central South Guangdong Line Foshan Interchange Station Kwun Tong Line West Island Line Dongguan HONG KONG SAR Shenzhen Metro Light Rail Shatin to Central Link Network Ma On Shan Line * Racing days only Tseung Kwan O Line Tai Wo Tsuen Wan Line Yuen Long Long Tung Chung Line Ping 44 West Rail Line 40 47 33 Kam Tai Po Market PROPERTIES OWNED / PROPERTY DEVELOPMENTS UNDER Sheung 48 Road DEVELOPED / MANAGED BY CONSTRUCTION / PLANNING 49 THE CORPORATION 34 LOHAS Park Package 2C-10 Tin Shui Wai Ma On Shan 36 50 01 Telford Gardens / Telford Plaza I and II 38 Che Kung Temple Station Wu Kai Sha 02 World-wide House 39 Tai Wai Station New Territories Heng On 03 Admiralty Centre 40 Tin Shui Wai Light Rail University 04 Argyle Centre 41 Austin Station Site C Siu Hong Tai Shui 05 Luk Yeung Sun Chuen / Luk Yeung 42 Austin Station Site D Hang Galleria 52 Wong Chuk Hang Station 06 New Kwai Fong Gardens 53 Ho Man Tin Station 27 07 Sun Kwai Hing Gardens 35 29 Tuen Mun Racecourse* 08 Fairmont House 30 -

Hong Kong's Border Regime and Its Role in National Sovereignty Aaron Mok [email protected]

Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity Volume 5 Article 12 Issue 1 Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal 4-11-2019 Hong Kong's Border Regime and its Role in National Sovereignty Aaron Mok [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Mok, A. (2019). Hong Kong's Border Regime and its Role in National Sovereignty. Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity, 5(1). Retrieved from https://orb.binghamton.edu/alpenglowjournal/vol5/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Alpenglow: Binghamton University Undergraduate Journal of Research and Creative Activity by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Hong Kong’s “One Country, Two Systems” government regime will end by 2047and it will promote the country’s integration into the People’s Republic of China (PRC). To ensure a smooth transition, by eliminating the border and other forms of geographic barriers that separate the two countries, the PRC has been issuing measures to promote integration. However, despite on-going practices of integration, Hong Kong continues to strengthen its border with China through infrastructural and bureaucratic means, reinforcing a British-colonial era border regime. Thus, my research focuses on this contradiction between the elimination and reinforcement of the Hong Kong-China border as an attempt to understand the socio-political forces that have produced this dynamic. -

A Bridge Between East and West: the Universities Service Centre of the Chinese University of Hong Kong

International Journal of Legal Information the Official Journal of the International Association of Law Libraries Volume 34 Article 10 Issue 3 Winter 2006 1-1-2006 A Bridge Between East and West: The niU versities Service Centre of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Duncan Alford Charlotte School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli The International Journal of Legal Information is produced by The nI ternational Association of Law Libraries. Recommended Citation Alford, Duncan (2006) "A Bridge Between East and West: The nivU ersities Service Centre of the Chinese University of Hong Kong," International Journal of Legal Information: Vol. 34: Iss. 3, Article 10. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol34/iss3/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Legal Information by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Bridge Between East and West: The Universities Service Centre of the Chinese University of Hong Kong DUNCAN ALFORD* Fragrant Harbor is the literal translation of the Chinese (pinyin Xiang Gang) for Hong Kong. Once a British colony and now a Special Administrative Region within the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong is also a global financial center. In June 2006 I had the privilege of conducting legal research as a visiting scholar at the Universities Service Centre of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.1 My research topic was the influence of Hong Kong banking law on banking reform in the People’s Republic of China. -

The Future of Frontier Closed Area By

THE FUTURE OF FRONTIER CLOSED AREA BY CHAN PAT FAN Student No.: 01014641 AN HONOURS PROJECT SUBMITTEDIN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (HONOURS) IN GEOGRAPHY HONG KONG BAPTIST UNIVERSITY 04/2004 HONG KONG BAPTIST UNIVERSITY April / 2004 We hereby recommend that the Honours Project by Mr. CHAN Pat Fan, entitled “The Future of Frontier Closed Area” be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Social Sciences (Honours) in Geography. _________________ _________________ Professor S. M. Li Dr. C. S. Chow Chief Adviser Second Examiner Continuous Assessment: _______________ Product Grade: _______________________ Overall Grade: _______________________ 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor S. M. LI for suggesting the research topic and guiding me through the entire study. In addition, also thank for staff of The Public Records Office of Hong Kong (PRO) provide me useful information and documentaries. _____________________ Student’s signature Department of Geography Hong Kong Baptist University Date: 5th April 2004 ___ 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF MAPS ---------------------------------------------------------------------I LIST OF TABLES ------------------------------------------------------------------II LIST OF PLATES ------------------------------------------------------------------III ABSTRACT--------------------------------------------------------------------------IV CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGORUND OF FRONTIER -

Memorandum of Understanding on Jointly Developing the Lok Ma

(English translation) Memorandum of Understanding on Jointly Developing the Lok Ma Chau Loop by Hong Kong and Shenzhen between the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government and the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Government Introduction In order to establish a “Hong Kong/Shenzhen Innovation and Technology Park” (“the Park”) in the Lok Ma Chau Loop (“the Loop”), the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“HKSAR”) Government and Shenzhen Municipal People’s Government (“both sides”) have agreed to jointly develop the Loop (actual location shown in the attached Plan 1). This Memorandum of Understanding (“the MOU”) is signed by both sides, following friendly negotiations. Background In accordance with Order No. 221 of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China promulgated on 1 July 1997 (the “State Council Order No. 221”), after the training of the Shenzhen River, the boundary will follow the new centre line of the river. The Loop, originally within the administrative boundary of Shenzhen, has since been included within the administrative boundary of the HKSAR. On 25 November 2011, both sides signed the Co-operation Agreement on Jointly Taking Forward the Development of the Lok Ma Chau Loop (“the Co-operation Agreement”). Out of respect for the above historical fact, both sides have agreed to co-operate in taking forward the Loop’s development under the “One Country, Two Systems” principle, and in accordance with the laws of the HKSAR, as well as following the principle of “co-development and mutual benefit”. Both sides subsequently conducted proactive negotiations in accordance with the Co-operation Agreement and reached a consensus to jointly develop the Loop into the Park, construct relevant higher education and complementary facilities in the Park and formulate this MOU. -

Essential-Guide-Shenzhen-Web.Pdf

The Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen Copyright © Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang 2016 Some Rights Reserved. First Edition, Web Export. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Publisher: Sutajio Ko-Usagi PTE LTD dba Kosagi, in Singapore. [email protected] Editor: Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang Design and Layout: Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang Translations: Celia Wang Translation errors: Andrew ‘bunnie’ Huang Illustrations: Miran Lipovača Printed in the People’s Republic of China. ISBN 978-981-09-7459-6 To Gavin Zhao For opening my eyes to the real China. You have been a great teacher and mentor; I can do now what I once thought was impossible. I hope you win your battle with cancer, so that you can continue to mentor and inspire more people like me. 5 Contents Introduction 7 Why Point to Translate instead of Phonetic? 9 Using the Guide 10 About Technical Chinese 11 What’s in the Market (And What’s Not) 12 Pricing the Market and Haggling 14 Is it Fake? 15 Hours & When to Go 18 Internet & Helpful Apps 19 Tipping 20 Weather & Dressing 20 Point-to-Translate Guide: Components 23 Point-to-Translate Guide: Tools & Tooling 45 Point-to-Translate Guide: Sealing the Deal 55 Point-to-Translate Guide: Getting Around 67 Getting To Shenzhen, and Back Again 83 Visas 84 Getting to the Border 85 Which Border Crossing to Use? 87 Time-Saving Tips for Crossing the Border 90 China Customs 91 Maps 95 Acknowledgments 123 6 The Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen bunnie 7 Introduction Introduction (shēn · zhèn) 8 The Essential Guide to Electronics in Shenzhen bunnie 9 Introduction Hello! This book is designed to help non-Mandarin speakers navigate the sprawling electronics markets of Shenzhen.