Hong Kong's Border Regime and Its Role in National Sovereignty Aaron Mok [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong Final Report

Urban Displacement Project Hong Kong Final Report Meg Heisler, Colleen Monahan, Luke Zhang, and Yuquan Zhou Table of Contents Executive Summary 5 Research Questions 5 Outline 5 Key Findings 6 Final Thoughts 7 Introduction 8 Research Questions 8 Outline 8 Background 10 Figure 1: Map of Hong Kong 10 Figure 2: Birthplaces of Hong Kong residents, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 11 Land Governance and Taxation 11 Economic Conditions and Entrenched Inequality 12 Figure 3: Median monthly domestic household income at LSBG level, 2016 13 Figure 4: Median rent to income ratio at LSBG level, 2016 13 Planning Agencies 14 Housing Policy, Types, and Conditions 15 Figure 5: Occupied quarters by type, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Figure 6: Domestic households by housing tenure, 2001, 2006, 2011, 2016 16 Public Housing 17 Figure 7: Change in public rental housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 18 Private Housing 18 Figure 8: Change in private housing at TPU level, 2001-2016 19 Informal Housing 19 Figure 9: Rooftop housing, subdivided housing and cage housing in Hong Kong 20 The Gentrification Debate 20 Methodology 22 Urban Displacement Project: Hong Kong | 1 Quantitative Analysis 22 Data Sources 22 Table 1: List of Data Sources 22 Typologies 23 Table 2: Typologies, 2001-2016 24 Sensitivity Analysis 24 Figures 10 and 11: 75% and 25% Criteria Thresholds vs. 70% and 30% Thresholds 25 Interviews 25 Quantitative Findings 26 Figure 12: Population change at TPU level, 2001-2016 26 Figure 13: Change in low-income households at TPU Level, 2001-2016 27 Typologies 27 Figure 14: Map of Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Table 3: Table of Draft Typologies, 2001-2016 28 Typology Limitations 29 Interview Findings 30 The Gentrification Debate 30 Land Scarcity 31 Figures 15 and 16: Google Earth Images of Wan Chai, Dec. -

ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong 3. Conference

ctbuh.org/papers Title: ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong Author: Tony Tang, Architect and Project Director of ICC, Sun Hung Kai Properties Limited Subjects: Architectural/Design Building Case Study Keywords: Building Management Connectivity Construction Design Process Façade Fire Safety Mixed-Use Passive Design Urban Planning Vertical Transportation Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: Cities to Megacities: Shaping Dense Vertical Urbanism Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Tony Tang ICC – Rising High for the Future of Hong Kong 环球贸易广场——香港未来新高度 Abstract | 摘要 Tony Tang Architect and Project Director of ICC | ICC建筑师和项目总监 Standing at 484 meters, Sun Hung Kai’s ICC is the tallest building in Hong Kong and currently the Sun Hung Kai Properties Limited 7th tallest in the world. ICC does not only add to the stock of the tall buildings in Hong Kong, it 新鸿基地产发展有限公司 also helps to transform the once barren West Kowloon district into a new business, cultural and Bangkok, Thailand transportation hub of Hong Kong. The building and its associated amenities have been planned 曼谷,泰国 and developed over a decade-long period. This has shown a careful master planning and Tony Tang graduated from The University of Hong Kong and has since practiced architecture and project management for collaborative execution among the developer, architect, engineers and facility managers. This over 25 years. Mr. Tang has participated in a number of major paper details the history, the concept and design of ICC as well as how the continuous devoted commercial and composite development projects in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing. -

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: a Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO

Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Tso, Elizabeth Ann Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 12:25:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/623063 DISCOURSE, SOCIAL SCALES, AND EPIPHENOMENALITY OF LANGUAGE POLICY: A CASE STUDY OF A LOCAL, HONG KONG NGO by Elizabeth Ann Tso __________________________ Copyright © Elizabeth Ann Tso 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE INTERDISCIPLINARY PROGRAM IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION AND TEACHING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Elizabeth Tso, titled Discourse, Social Scales, and Epiphenomenality of Language Policy: A Case Study of a Local, Hong Kong NGO, and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Perry Gilmore _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Wenhao Diao _______________________________________________ Date: (January 13, 2017) Sheilah Nicholas Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

1. Introduction 2. UHI in Hong Kong 3. Trends in Extreme UHI 4. Conclusion

Urban heat islands in Hong Kong: Statistical modeling and trend detection 1,2 3 2, 4, 5 4 Weiwen Wang , Wen Zhou , Edward Yan Yung Ng , Yong Xu 1. Institute for Environmental and Climate Research, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China 2. School of Architecture, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 3. Guy Carpenter Asia-Pacific Climate Impact Centre, School of Energy and Environment, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 4. Institute of Future Cities, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 5. Institute of Environment, Energy and Sustainability, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 1. Introduction 3. Trends in extreme UHI Urban heat islands (UHIs), usually defined as temperature differences Extreme UHI events are defined as UHIs with intensity higher than a between urban areas and their surrounding rural areas, are one of the most specific threshold, 4.8°C for summer and 7.8°C for winter. Statistical modeling significant anthropogenic modifications to the Earth’s climate. This study applies based on extreme value theory is found to permit realistic modeling of these the extreme value theory to model and detect trends in extreme UHI events in extreme events. Trends of extreme UHI intensity, frequency, and duration are Hong Kong, which have rarely been documented. introduced through changes in parameters of generalized Pareto, Poisson. As illustrated in Fig. 1, large developments occurred in New Territories In summer, the trend is 0.042 and 0.011 for intensity and frequency per (northern Hong Kong) and in nearby Shenzhen. -

For Discussion on 28 October 2008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL

For discussion on 28 October 2008 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON DEVELOPMENT Development of Liantang/Heung Yuen Wai Boundary Control Point PURPOSE This paper briefs Members on the development of Liantang/Heung Yuen Wai boundary control point (LT/HYW BCP). BACKGROUND 2. On 27 May 2008, we briefed Members on the work of Hong Kong-Shenzhen (HK-SZ) Joint Task Force on Boundary District Development (港深邊界區發展聯合專責小組) (the JTF). Members were informed of the progress of two related planning studies on the proposed BCP at LT/HYW: the “SZ-HK Joint Preliminary Planning Study on Developing LT/HYW BCP” and the internal “Planning Study on LT/HYW BCP and Its Associated Connecting Roads in HK”. 3. Both studies were completed in June 2008. The HK Special Administrative Region Government (HKSARG) and the SZ Municipal People’s Government jointly announced the implementation of the new BCP after the second meeting of the JTF on 18 September 2008. Both sides will proceed with their detailed planning and design work with an aim to commence operation of the new BCP in 2018. A Working Group on Implementation of LT/HYW BCP (蓮塘/香園圍口岸工程實施工作小組) has been set up under the JTF to co-ordinate works of both sides. A LegCo brief summarizing the findings of the studies and scope of the new BCP development was issued on the announcement day (Appendix 1). 4. On the HK side, the development of LT/HYW BCP comprises the construction of a BCP with a footprint of about 18 hectares (including an integrated passenger clearance hall), a dual 2-lane trunk road of about 10 km in length, and improvement works to SZ River of about 4 km in length. -

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development

Preliminary Concepts for the New Territories North Development 02 OverviewOOvveveerrvieeww 04 ExistingEExExixisxixisssttitinng CConditionsonondddiittioonnsns 07 OpportunitiesOOppppppoortunnittiiieeses & CoCConstraintsoonnssstttrraaiainntnntss 08 OverallOOvveveerall PPlanninglananniiinnngg ApAApproachespppprrooaoacaachchchehhesess 16 OverallOOvveeraall PPlPlanninglalaannnnnniiinnngg & DesignDDeesessign FrameworkFrarammeeewwoworrkk 20 BroadBBrBroroooaadd LandLaLandnd UUsUseses CoCConceptsoonnccecepeptptss 28 NextNNeexexxt StepStStept p Overview Background 1.4 The Study adopts a comprehensive and integrated approach to formulate the optimal scale of development 1.1 According to the latest population projection, Hong in the NTN. It has explored the potential of building new Kong’s population would continue to grow, from 7.24 communities and vibrant employment and business million in 2014 to 8.22 million by 2043. There is a nodes in the area to contribute to the long-term social continuous demand for land for economic development and economic development of Hong Kong. to sustain our competitiveness. There are also increasing community aspirations for a better living environment. 1.5 The Study is a preliminary feasibility study which has examined the baseline conditions of the NTN covering 1.2 To maintain a steady land supply, the Government is about 5,300 hectares (ha) of land (Plan 1) to identify looking into various initiatives, including exploring further potential development areas (PDAs) and formulate an development opportunities in the -

Intermediates1#1 Gettingajobinhongkong

LESSON NOTES Intermediate S1 #1 Getting a Job in Hong Kong CONTENTS 2 Traditional Chinese 2 Jyutping 3 English 3 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 6 Vocabulary Phrase Usage 6 Grammar 7 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. TRADITIONAL CHINESE 1. A: 2. B: 3. A: 4. B: 5. A: 6. B: 7. A: "" 8. B: JYUTPING 1. A: ze3 man6 seng1, ni1 dou6 hai6 mai6 ceng2 jan4 aa3 ? 2. B: hai6, nei5 soeng2 gin3 bin1 fan6 gung1 ? 3. A: ngo5 hai6 lei4 jing3 ping3 coi4 mou3 ging1 lei5 ge3. 4. B: hai2 ni1 hong4 zou6 zo2 gei2 noi6 ? 5. A: ngo5 aam1 aam1 bat1 jip6, zung6 bin1 zou6 bin1 hok6. 6. B: gam2 nei5 gok3 dak1 zi6 gei2 jau5 me1 jau1 sai3 ? CONT'D OVER CANTONES ECLAS S 101.COM INTERMEDIATE S1 #1 - GETTING A JOB IN HONG KONG 2 7. A: ngo5 hai2 sei3 daai6 sat6 zaap6 zo2 bun3 nin4, jau5 wui6 gai3 si1 paai4. 8. B: hou2, min6 si5 git3 gwo2 ngo5 dei6 wui5 jau5 zyun1 jan4 tung1 zi1 nei5. ENGLISH 1. A: Excuse me, is the company looking for employees? 2. B: Yes, what kind of position are you looking for? 3. A: I'm here for the financial manager position. 4. B: How long have you been working in this field? 5. A: I've just graduated. I'm looking for work while I learn more. 6. B: So, why do you think you're a good hire? 7. A: I've been an intern with one of the Top Four accounting companies for half a year, and I've got an accounting certificate. -

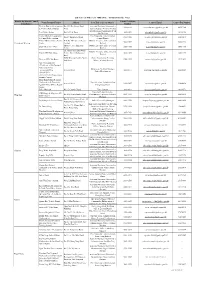

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

新成立/ 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單list of Newly Incorporated

This is the text version of a report with Reference Number "RNC063" and entitled "List of Newly Incorporated /Registered Companies and Companies which have changed Names". The report was created on 14-09-2020 and covers a total of 2773 related records from 07-09-2020 to 13-09-2020. 這是報告編號為「RNC063」,名稱為「新成立 / 註冊及已更改名稱的公司名單」的純文字版報告。這份報告在 2020 年 9 月 14 日建立,包含從 2020 年 9 月 7 日到 2020 年 9 月 13 日到共 2773 個相關紀錄。 Each record in this report is presented in a single row with 6 data fields. Each data field is separated by a "Tab". The order of the 6 data fields are "Sequence Number", "Current Company Name in English", "Current Company Name in Chinese", "C.R. Number", "Date of Incorporation / Registration (D-M-Y)" and "Date of Change of Name (D-M-Y)". 每個紀錄會在報告內被設置成一行,每行細分為 6 個資料。 每個資料會被一個「Tab 符號」分開,6 個資料的次序為「順序編號」、「現用英文公司名稱」、「現用中文公司名稱」、「公司註冊編號」、「成立/ 註冊日期(日-月-年)」、「更改名稱日期(日-月-年)」。 Below are the details of records in this report. 以下是這份報告的紀錄詳情。 1. 1 August 1996 Limited 0226988 08-09-2020 2. 123 Management Limited 123 管理有限公司 2975249 07-09-2020 3. 12F Studio Company Limited 12 樓工作室有限公司 2975397 07-09-2020 4. 1more Storm Limited 2975821 08-09-2020 5. 20 Two North Limited 2975101 07-09-2020 6. 22 CONSULTING SERVICES LIMITED 1464602 09-09-2020 7. 2pickss Limited 驛站自取點有限公司 2738276 08-09-2020 8. 2ZWEI SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT LIMITED 2976308 10-09-2020 9. 3A International Limited 2975426 07-09-2020 10. 6gNetworks Technology Co., Limited 2976682 10-09-2020 11. -

Legislative Council Panel on Transport Subcommittee on Matters Relating to Railways Retrofitting of Automatic Platform Gates On

LC Paper No. CB(1)1072/10-11(02) Legislative Council Panel on Transport Subcommittee on Matters Relating to Railways Retrofitting of Automatic Platform Gates on the East Rail Line Purpose This paper aims to present the results and conclusions of the technical studies regarding the retrofitting of automatic platform gates (APGs) on the East Rail Line (EAL). Background 2. All MTR train platforms have been designed and built to international standards. Supplemented with additional safety warning devices and measures as well as regular educational activities on platform safety, a safe travelling environment is provided for MTR passengers. 3. While international standards do not require APGs for safe railway operations and APGs are not installed in most of the world’s railways, voices in the Hong Kong community have, for a variety of reasons, requested APGs to be retrofitted in the MTR platforms that currently do not have them. 4. Work is now in progress to install APGs at eight at-grade and above-ground stations on the Kwun Tong, Tsuen Wan and Island Lines. 5. Regarding the retrofitting of APGs at EAL stations, technical studies have been conducted with a view to identifying feasible solutions. However, the studies reveal that retrofitting of APGs at EAL stations poses particularly difficult challenges. They include - (a) safety risk associated with wide platform gaps; (b) limitations of existing signalling system; (c) limitations of existing trains; and (d) limitations of platform structures. 1 Safety risk associated with wide platform gaps and the trial of mechanical gap fillers 6. Platform gaps are required in safe train operations to prevent trains in motion from hitting the platform when arriving and departing a station. -

General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921

Access Officer - Hongkong Post District Venue/Premise/Facility Address Post Title of Access Officer Telephone Number Email Address Fax Number General Post Office 2 Connaught Place, Central Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 G/F, Kennedy Town Community Complex, 12 Rock Kennedy Town Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Hill Street, Kennedy Town Shop P116, P1, the Peak Tower, 128 Peak Road, the Peak Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Peak Central and Western Sai Ying Pun Post Office 27 Pok Fu Lam Road Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 1/F, Hong Kong Telecom CSL Tower, 322-324 Des Sheung Wan Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Voeux Road Central Wyndham Street Post Office G/F, Hoseinee House, 69 Wyndham Street Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester Road Post Office 1/F, Revenue Tower, 5 Gloucester Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Happy Valley Post Office G/F, 14-16 Sing Woo Road, Happy Valley Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Morrison Hill Post Office G/F, 28 Oi Kwan Road, Wan Chai Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Wan Chai Wan Chai Post Office 2/F Wu Chung House, 197-213 Queen's Road East Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Perkins Road Post Office G/F, 5 Perkins Road, Jardine's Lookout Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Shops 1015-1018, 10/F, Windsor House, 311 Causeway Bay Post Office Postmaster 2921 2222 [email protected] 2868 0094 Gloucester -

Hansard (English)

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 20 October 2010 241 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 20 October 2010 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, S.B.S., J.P. 242 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 20 October 2010 THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW CHENG KAR-FOO THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LI FUNG-YING, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE AUDREY EU YUET-MEE, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, M.H.