Abdullah Cevdet and the Baha'i Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doktor Abdullah Cevdet'te Din Algısı

Demir / Doktor Abdullah Cevdet’te Din Algısı Doktor Abdullah Cevdet’te Din Algısı Osman Demir* Öz: Osmanlı coğrafyasında Batı kaynaklı akımların hızla yayılmaya başladığı bir dönemde yaşa- yan Abdullah Cevdet, savunduğu fikirler ve bunları ifade etme biçimiyle çokça tartışılan kişilerden biridir. Dindar bir ailede dünyaya gelmekle birlikte zamanla materyalizme kayan Abdullah Cevdet, fikirlerini yaymak için telif ve çeviri faaliyetine girişmiş ve bu süreç, onun din algısının şekillenme- sinde etkili olmuştur. Onun din hakkındaki görüşleri, iç dünyasındaki dalgalanmalara ve dönemin şartlarına bağlı olarak da değişmektedir. Abdullah Cevdet’in pratik dindarlığın sorunlarına yöne- lik görünen eleştirileri, dinin en temel kavramlarını sorgulayan ve bunlar üzerinde ciddi şüpheler uyandıran bir noktaya varmaktadır. Bu nedenle, hem yaşadığı dönemde hem de sonrasında din- sizlikle itham edilen Cevdet, materyalizmin ülkeye girmesine önayak olan isimlerin başında gös- terilmiştir. Cevdet’in, bilimsel maddeciliğe ulaşmak için dini bir araç olarak kullanıp İslam dininin içeriğinden yararlandığı, ayrıca dine değil, taassuba ve dinin yanlış uygulamalarına karşı oldu- ğuna dair birtakım görüşler de ileri sürülmüştür. Bu makalede, yaptığı çalışmalarla Cumhuriyet dönemi din politikalarını ve toplumun din anlayışını önemli ölçüde etkileyen Abdullah Cevdet’in din algısı, başlıklar halinde ele alınacak; onun, dinî konu ve kavramlar üzerinde ciddi tereddütlere ve yıkıcı etkilere sebebiyet veren bir sorgulama tarzını benimsediği gösterilecektir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Abdullah Cevdet, Materyalizm, Din, Batılılaşma. Abstract: Doctor Abdullah Cevdet, who lived in a period in which trends of western origin were spreading rapidly in the Ottoman territory, is among the individuals who have been frequently discussed because of the ideas he defended and the manner in which he expressed them. Even though he was born into a devout family, he turned towards materialism and translated many works to Turkish, aiming to spread his views. -

Osmanlı Devleti'nde Jön Türk Hareketinin Başlaması Ve Etkileri

OSMANLı DEVLETİ'NDE JÖN TÜRK HAREKETİNİN BAŞLAMASı VE ETKİLERİ Yrd. Doç. Dr. Durdu Mehmet BURAK* GİRİş Jön Türkler: Osmanlı Devleti içinde 19. yüzyılın ikinci yarı- sında Meşrut! bir temele dayalı bir sistem kurmak, Kanun-i Esasi ilanıyla da serbest seçimlere gitmek ve böylece oluşturulacak mec- lise, ülke geleceğini teslim etmek gibi fikirlerle yola çıkan, hedef olarak batı örnekliğini seçen Osmanlı aydınlarının ortak adıdır. Bu isim ilk olarak Mustafa Fazıl Paşa'nın yayınladığı bir arlzada kulla- nılmış ve sonradan Namık Kemal ve Ali Suavi tarafından Yeni Os- manlılar karşılığı olarak benimsenmiştir. Ayrıca, ı. ve II. Meşrutiyet dönemlerinde de bütün ihtilalciler için bu isim kullanılmıştır. Jön Türk hareketi, Osmanlı tarihinin son kesitinde en önemli sosyal ve siyasal harekettir. Belki de Osmanlı tarihinde böyle bir orijinallik ve tipiklik az rastlanan bir örnektir. Jön Türkler'den İtti- hat ve Terakki 'ye uzanan yolda Osmanlı temelinden sarsılmıştır. Kuruluş ve başlangıç noktaları ile sonuçları farklı neticeler doğuran hareket, hem bir felaket hem de geleceği etkileyen bir kaosa dönüş- müştür. Tarihimizde Jön Türkler konusu, aydınlanmamış, karanlık yön- leriyle hala önemini ve ilgi çekme özelliğini korumaktadır. Jön Türklerin Türk tarihine damgasını vurdukları 1890-1918 yılları ara- sı, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun çöküşünün hızlanıp tamamlandığı bir dönem olmuştur. Bir çöküşü n yanında, bir kuruluşun oluşumu- * Gazi Üniversitesi. Kırşehir Eğitim Fakültesi. Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Bölümü, Öğretim Üyesi. 292 DURDU MEHMET BURAK nun temel izahıarı, bu dönem içinde yatmaktadır. Bu bakımdan, adı geçen çöküş ve kuruluşu iyi anlamak için ı890- ı9 ı8 zaman dili- mindeki olayların gerçek anlamda bilinmesi ve izahı gerekmekte- dir. Jön Türkler üzerine yazılmış yüzlerce eser mevcuttur. Şu ana kadar altmışın üzerinde incelediğim kaynak eserlerde Jön Türk ha- reketlerini daha iyi anlayabilmek için dönemin gelişen hadiselerini de inceleme lüzumunu hissettim. -

History&Future Tarih&Gelecek

e-ISSN 2458-7672 Tarih ve Gelecek Dergisi, Aralık 2020, Cilt 6, Sayı 4 1487 https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/jhf Journal of History and Future, December 2020, Volume 6, Issue 4 Tarih&GelecekDergisi HistoryJournal of &Future Çankırı Karatekin Üniversitesi Öğr. Gör. Dr. Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Bölümü, Ebubekir KEKLİK E-mail: ebubekirkeklik@hotmail. com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7982-8980 JHF Başvuruda bulundu. Kabul edildi. Applied Accepted Eser Geçmişi / Article Past: 26/10/2020 08/11/2020 Araştırma Makalesi DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21551/jhf.816360 Research Paper Orjinal Makale / Orginal Paper İkinci Meşrutiyet Döneminde Eğitim Sorunu ve Osmanlı Aydınları* Education Problem and Ottoman Intellectuals in the Second Constitutional Era Öz İkinci Meşrutiyet’in ilanı Osmanlı düşünce hayatına büyük canlılık getirmiştir. Özellikle II. Abdülhamid döneminde üzerinde konuşulamayan, tartışılamayan konular, en azından İttihad ve Terakki’nin mutlak iktidar yıllarına kadar serbestlik içerisinde tartışılabilmiştir. II. Abdülhamid dönemi eğitim alanında önemli gelişmeler yaşanan bir devirdir; fakat eğitim meselesi de diğer pek çok mesele gibi yeterince tartışılamayan konulardandı. Ancak meşrutiyetin ilanıyla hem modern eğitim düzeninin gelişimi yeni bir ivme kazandı hem de eğitim sorunu yeniden ele alındı. Bu dönemde aynı zamanda modern eğitim-öğretim kurumlarındaki niceliksel büyüme de devam etti. XIX. yüzyılda başlayan, kitlesel eğitimin ülkeyi kurtaracak temel dayanaklardan biri olduğu düşüncesi İkinci Meşrutiyet döneminin eğitim anlayışına da damga vurmuştur. Batmakta olan imparatorluğu bir eğitim ordusunun kurtaracağı düşüncesi bu dönem aydınlarının çoğunun ortak düşüncesidir. Bu sebeple öğretmenlik mesleği ayrı bir önem kazanmıştır. İmparatorluğu kurtaracak eğitimli nesillerin, idealist bir öğretmen ordusu tarafından yetiştirileceği düşüncesi bir inanca dönüşmüştür. Özellikle Balkan Savaşları’nda alınan ağır mağlubiyet Osmanlı aydınlarının eğitim meselesine daha bir ciddiyetle eğilmelerine yol açmıştır. -

Science Versus Religion: the Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960

Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Serdar Poyraz, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway Alan Beyerchen Copyright By Serdar Poyraz 2010 i Abstract My dissertation, entitled “Science versus Religion: The Influence of European Materialism on Turkish Thought, 1860-1960,” is a radical re-evaluation of the history of secularization in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. I argue that European vulgar materialist ideas put forward by nineteenth-century intellectuals and scientists such as Ludwig Büchner (1824-1899), Karl Vogt (1817-1895) and Jacob Moleschott (1822-1893) affected how Ottoman and Turkish intellectuals thought about religion and society, ultimately paving the way for the radical reforms of Kemal Atatürk and the strict secularism of the early Turkish Republic in the 1930s. In my dissertation, I challenge traditional scholarly accounts of Turkish modernization, notably those of Bernard Lewis and Niyazi Berkes, which portray the process as a Manichean struggle between modernity and tradition resulting in a linear process of secularization. On the basis of extensive research in modern Turkish, Ottoman Turkish and Persian sources, I demonstrate that the ideas of such leading westernizing and secularizing thinkers as Münif Pasha (1830-1910), Beşir Fuad (1852-1887) and Baha Tevfik (1884-1914) who were inspired by European materialism provoked spirited religious, philosophical and literary responses from such conservative anti-materialist thinkers as Şehbenderzade ii Ahmed Hilmi (1865-1914), Said Nursi (1873-1960) and Ahmed Hamdi Tanpınar (1901- 1962). -

THE INFLUENCE of AL-MANAR on ISLAMISM in TURKEY the Case of Mehmed Âkif

4 THE INFLUENCE OF AL-MANAR ON ISLAMISM IN TURKEY The case of Mehmed Âkif Kasuya Gen In the years from 1908 to 1918, starting with the 1908 revolution that opened the floodgates for publication up till the Ottoman defeat in the First World War, intellectual circles in the Ottoman Empire eagerly took up the discussion of the place and role of Islam in Ottoman society. The so-called “Islamic modernism” or “Islamic reformism,” often used interchangeably with movements calling for ıslah (reform), ihya (revival), and tecdid (renewal), was one of the most influential current within the Empire. It is sometimes mentioned that the ideas of the three major modern Salafi thinkers in the Arab world, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838–1897), Muhammad 2Abduh (1849–1905), and Rashid Rida (1865–1935), were the ideological roots of Islamism (⁄slamcılık in Turkish) in the Ottoman Empire during this period. Their ideas of Islamic reform permeated the articles in al-2Urwa al-Wuöqa (“The Indissoluble Bond”) published by Afghani and 2Abduh in Paris in 1884, and Rida’s periodical al-Manar (“The Lighthouse,” 1898–1935), whose impact was felt on Islamic currents throughout the Muslim world. This article is meant to be a reexamination of the impact of al-Manar and the “Manarists” on the development of Islamism in Turkey from 1908 to 1918. Islamism (⁄slamcılık) in Ottoman thought after 1908 Before engaging in a discussion of the impact of al-Manar and of the Manarists on Islamism (⁄slamcılık) in Turkey, we will begin by categorizing Islamism as it appears within Ottoman intellectual currents after 1908. -

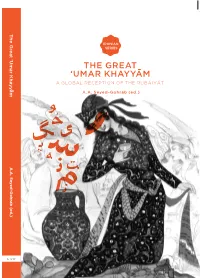

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Philosophical Movements in Ottoman Intellectual Life at the Beginning of the 20Th Century and Their Impact on Young Turk’S Thought

PHILOSOPHICAL MOVEMENTS IN OTTOMAN INTELLECTUAL LIFE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY AND THEIR IMPACT ON YOUNG TURK’S THOUGHT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FATİH TAŞTAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY SEPTEMBER 2013 i Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Yasin Ceylan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Yasin Ceylan (METU, PHIL) Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam (METU, PHIL) Prof. Dr. Erdal Cengiz (A. U., DTCF) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif Çırakman (METU, PHIL) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ertuğrul R. Turan (A. U., DTCF.) ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Fatih Taştan Signature : iii ABSTRACT PHILOSOPHICAL MOVEMENTS IN OTTOMAN INTELLECTUAL LIFE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY AND THEIR IMPACT ON YOUNG TURK’S THOUGHT Taştan, Fatih Ph. D., Department of Philosophy Supervisor: Prof. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. There is, of course, no consensus on the precise meaning of democracy, much less dem- ocratic values. 2. Also sometimes known as the Constitution of Medina. The original document has not survived, but a number of different versions can be found in early Muslim sources. 3. The word caliph is derived from the Arabic khalifa, which means both “successor” and “deputy.” 4. In Arabic, Shari’a literally means the “path leading to the watering place.” 5. The word “Shia” is derived from the Arabic Shiat Ali, meaning “party of Ali.” While “Sunni” means those who follow the Sunnah, the exemplary words and practices of the Prophet Muhammad. The names are misleading, as Ali is revered by the Sunni—albeit not to the same extent as by the Shia—and the Shia also attach great importance to the Sunnah. 6. Starting with Ali through to Muhammad al-Mahdi, who received the imamate in 874 at the age of five. Muhammad was taken into hiding to protect him from his Sunni enemies. However, in around 940 he is regarded as having left the world materially but to have retained a spiritual presence through which he guides Shia divines in their interpretations of law and doctrine. Twelvers believe that he will eventually return to the world as the Mahdi, or “Messiah,” and usher in a brief golden age before the end of time. There have also been divisions within the Shia community. In the eighth century, during a dispute over the rightful heir to the sixth imam, Jafar al-Sadiq, the Twelvers backed the candidacy of a younger son, Musa al-Kazim. -

Ataturk's Reforms: Realization of an Utopia by a Realist (*)

ATATURK'S REFORMS: REALIZATION OF AN UTOPIA BY A REALİST (*) By Artun ÜNSAL "The revolutionaries are thoso wlıo are capable of understanding the real aspirations in the mind and the conscience of the people whom they desire to orient towards the revolution of progress and renovation". Atatürk (1925). Abdullah Cevdet, a well-known Turkish writer of the beginning of the century, believed, as did many others, that "There is no second civilization; civilization means European civilization, and it must be imported with batlı its roses and thorns".1 According to him, the rulers of the Ottoman Empire had to abandon the policy of "half-way" borrowings and try to adopt so-called Western civilization. In other words, Turkey had no other way out, but to integrate herself thoroughly into European civilization. A series of articles (**) that appeared in his periodical İçtihad in 1912 under the title "A Very Wakeful Sleep" (Pek Uyanık Bir Uyku), described a visionary view of the future for the country that certainly must have appeared fantastic to his contemporaries. The reverie contained such re- volutionary novelties as : "The Sultan would have one wife and no concubins; tho princes would be removed from the care of eunuch and ha- rem servants, and given a thorough education, including sor- (*) Paper presented to the Semlnar on Nehru and Atatürk, New Delhi, 28 November 1981. (**) Unsigned, but most probably written by Kılıçzade Hakkı. 1 Quoted by Bernard Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey, London: Oxford University Press, 1965, p. 231. 28 THE TURKISH -

Changing Identities at the Fringes of the Late Ottoman Empire: the Muslims of Dobruca, 1839-1914

Changing Identities at the Fringes of the Late Ottoman Empire: The Muslims of Dobruca, 1839-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Catalina Hunt, Ph.D. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Carter V. Findley, Advisor Jane Hathaway Theodora Dragostinova Scott Levi Copyright by Catalina Hunt 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the Muslim community of Dobruca, an Ottoman territory granted to Romania in 1878, and its transformation from a majority under Ottoman rule into a minority under Romanian administration. It focuses in particular on the collective identity of this community and how it changed from the start of the Ottoman reform era (Tanzimat) in 1839 to the outbreak of World War I in 1914. This dissertation constitutes, in fact, the study of the transition from Ottoman subjecthood to Romanian citizenship as experienced by the Muslim community of Dobruca. It constitutes an assessment of long-term patterns of collective identity formation and development in both imperial and post-imperial settings. The main argument of the dissertation is that during this period three crucial factors altered the sense of collective belonging of Dobrucan Muslims: a) state policies; b) the reaction of the Muslims to these policies; and c) the influence of transnational networks from the wider Turkic world on the Muslim community as a whole. Taken together, all these factors contributed fully to the community’s intellectual development and overall modernization, especially since they brought about new patterns of identification and belonging among Muslims. -

Translating and Printing the Qurʾan in Late Ottoman and Modern

The Qurʾan After Babel: Translating and Printing the Qurʾan in Late Ottoman and Modern Turkey by M. Brett Wilson Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Dr. Bruce Lawrence, Supervisor ___________________________ Dr. Carl Ernst ___________________________ Dr. Erdağ Göknar ___________________________ Dr. Charles Kurzman ___________________________ Dr. Ebrahim Moosa Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. of Philosophy in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT The Qurʾan After Babel: Translating and Printing the Qurʾan in Late Ottoman and Modern Turkey by Michael Brett Wilson Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Dr. Bruce Lawrence, Supervisor ___________________________ Dr. Carl Ernst ___________________________ Dr. Erdağ Göknar ___________________________ Dr. Charles Kurzman ___________________________ Dr. Ebrahim Moosa An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Michael Brett Wilson 2009 Abstract This dissertation examines the translation and printing of the Qurʾan in the late Ottoman Empire and the early years of the Republic of Turkey (1820-1938). As most Islamic scholars deem the Qurʾan inimitable divine speech, the idea of translating the Qurʾan has been surrounded -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1 . Quoted from BBC News, “Iraq Prepares to Launch Bond Market,” Friday July 16, 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/3900627.stm accessed 11/06/2009. 2 . Public Record Office, FO 800/184A and 185A, 13 November 1908 (Grey Papers), quoted by Feroz Ahmed in Marian Kent (ed.), The Great Powers and the End of the Ottoman Empire (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1984), 13. 3 . Egyptian nationalist Mu ṣṭ af ā K ā mil’s well-known Arabic book on Japan, al-Shams al-Mushriqa (Cairo: al-Liw ā’ , 1904) is a direct translation of “The Rising Sun.” 4 . T. Sato, “al-Y ā b ā n ī ,” Encyclopaedia of Islam on CD-ROM (hereafter cited as EI ) [XI: 223a]; see also “W ā ḳ w ā ḳ ” [XI: 103b]. 5 . When Japanese naval officers came ashore from the Kongo and Hiei warships anchored on the Bosphorus in Istanbul in 1891, rumors abounded. They drew crowds when they used the local ham â ms, which made extra money for shopkeep- ers and bath-owners. Ziya Ş akir (Soku) Sultan Hamit ve Mikado . ( İ stanbul: Bo ğ azi ç i Yay ı nlar ı , 1994, 2nd edition), 86. 6 . There is substantial historiography of Orientalist views of Meiji Japan. See Akane Kawakami, Travellers’ Visions: French Literary Encounters with Japan, 1881–2004 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005); Sir Hugh Cortazzi and Gordon Daniels (eds.), Britain and Japan 1859–1991 (New York: Routledge, 1991); Olive Checkland, Britain’s Encounter with Meiji Japan, 1868–1912 (London: MacMillan Press, 1989); Toshio Yokohama, Japan in the Victorian Mind: A Study of Stereotyped Images of a Nation 1850–80 (London: The MacMillan Press, 1987); C.