Working Ontologists” and “High-Quality Human Components”: the Politics of Semantic Infrastructures 326 Doris Allhutter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

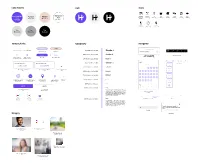

Color Palette Typography Header 1 Navigation Imagery Logo

Color Palette Logo Icons Background Brand/Highlight Highlight Highlight Dates Page/ Restaurant Bar Coffee Movies The Arts Music Sports /Text Date on date (location tag) (location tag) (location tag) (location tag) (location tag) (location tag) (location tag) /Text #EDEDED #F1D7CA plan page #6A42ED #FFFFFF Outdoors Time Location (location tag) (Date plan page) (Date plan page) Text Text Text #DDDDDD #AAAAAA #000000 Buttons/Links Typography Navigation Button Button Ready to go on a date? Open drop down menu Close drop down menu Source Serif Pro, s: 36, Bold Header 1 4 1 Inactive primary CTA Secondary CTA Enable “Set Up a Date” Feature Private until you both have enabled Button Button IBM Plex Sans, s: 30, Semi-Bold Header 2 Popup with the Enable a date Bottom navigation menu feature on the match chat page Inactive toggle state Active toggle state Primary CTA Tertiary CTA and Filters (enable setup feature) (enable setup feature) IBM Plex Sans, s: 21, Semi-Bold Header 3 Activity Price Rating April Source Serif Pro, s: 24, Bold Subheader 1 Who do you want to date? Who do you want to date? Recommended Filters (expanded) S M T W T F S Select a Match Erin Matthews New Spots IBM Plex Sans, s: 18, Semi-Bold Subheader 2 1 2 3 4 Upcoming Events Setup a Date Buttons (nothing Setup a Date Buttons (selection Close button (used for popout selected made) screens) Get a Drink IBM Plex Sans, s: 15, Semi-Bold Subheader 3 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Get some Food 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 IBM Plex Sans, s: 24, Semi-Bold Button 1 See a Movie Add Add 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Get Outside Add button for set up a date Add button for set up a date Location selector on Location selector on IBM Plex Sans, s: 13, Semi-Bold Button 2 Back button 26 27 28 29 30 Sports options (inactive) options (active) map view (current) map view (not-current) Listen to Music IBM Plex Sans, s: 9, Medium Button 3 May Add 6:00 PM 6:00 PM S M T W T F S IBM Plex Sans, s: 14, Medium Body 1 Setup a date button (selected Setup a date button This is an example of a body text paragraph. -

Typographers'

TUGboat, Volume 39 (2018), No. 1 17 Typographers’ Inn Peter Flynn Fonts and faces and families I suppose we’ve all but given up the unequal strug- gle to distinguish between a family, a face, and a font. I still use the terms separately, out of force of habit, but some work we were doing recently (see ‘X LE ATEX’ below) allowed me to identify many good examples. One family I installed recently (following its announcement on comp.text.tex) was IBM Plex, which is composed of these faces: 1. Plex Serif 12. Plex Sans SemiBold Figure 1: IBM Plex in action 2. Plex Serif ExtraLight 13. Plex Sans Text 3. Plex Serif Light 14. Plex Sans Thin 4. Plex Serif Medium 15. Plex Mono 5. Plex Serif SemiBold 16. Plex Mono ExtraLight 6. Plex Serif Text 17. Plex Mono Light ports. maybe four if we include theses) it’s usually 7. Plex Serif Thin 18. Plex Mono Medium much more important that the choice of typeface 8. Plex Sans 19. Plex Mono SemiBold remains unnoticed. It’s not that the choice is unim- 9. Plex Sans ExtraLight 20. Plex Mono Text portant, but that it’s more subtle than just choosing 10. Plex Sans Light 21. Plex Mono Thin a ‘font’ that you like the look of, although that is 11. Plex Sans Medium obviously part of the decision. In the days of metal type, even the largest print- I numbered them on a slide for a training course ers would have had only a tiny fraction of the type- so that the students could see the seven serif, seven faces available to the average computer user today: sans, and seven monospace components — and with a designer specifying a face not on hand would have luck, understand the distinction — before explaining had to cost-justify the rental of the matrices needed that each one came in the four standard font variants: to cast it, or (in smaller houses) buying sorts in regular, bold, italic, and bold-italic; making 84 in all. -

The Emerald Review Cw Sb 1 2 3 4 5 6

Can Trophy Hunting The Save Elephants? pg. 6 Forest Offsets in Emerald Western Mass. pg. 27 Beauty and the Review Waste pg. 38 @ Boston University 2017-2018 China’s Investment in Africa and its Natural Resources Accuracy in Today’s Uncertain World of “SciComms” 1 CONTENTS Life Industry 6 Can Revenue From Trophy 34 Environmental Impacts of Hunters Save Zimbabwe’s Hollywood Elephants? 37 The Untapped Potential of 10 Increasing Anthropogenic Solar Microgrids Noise: Drowining out the Whales 39 Beauty and the Waste: The Environmental Impact of 13 The Green Gray Area: How Fashion Industry to Actually Save the Bees 30 Mixed Messages and Slick 16 The Past Present and Lobbying from Exxon Future of Animal Testing Executives Media 40 Accuracy in Uncertainty: The Challenges of Reporting on Climate Change 44 Is Climate Change Entertainment? Impact 46 The Role of Female Education in the Fight A Closer Look at China’s 18 Against Climate Change Investment in Africa 23 The Trump Administration’s Efforts to Urban Cripple the EPA 48 A More Connected Massachusetts 25 Clean Water Rule Repeal: Carte Blanch to 52 Uncertain Outcomes: The Manufacters or Challenges of Environmental Protection Privately-Funded Transit 27 Forest Offsets Show 55 Cigarette Butt Litter: A Promise in Western Problem Left Unnoticed Massachusetts 2 3 STAFF THE EMERALD REVIEW CW SB 1 2 3 4 5 6 he past year for the review has been fast and transformative. We wel- 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Tcomed new faces, new articles, and new environmental challenges to over- come. After due consideration, the editorial staff endorsed The Emerald Review as the new name with the hopes of strengthen- 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 ing the position and brand of the review into the future. -

Bachelor's Thesis 19 3

Designing a Typeface for a Brand Ricardo Armando Tranquille BACHELOR’S THESIS September 2019 Media & Arts Interactive Media 2 ABSTRACT Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme in Media and Arts Interactive Media TRANQUILLE, RICARDO: Designing a Typeface for a Brand Bachelor's thesis 47 pages November 2019 The purpose of this thesis was to show how a custom font is made. This was done, first of all, through an introduction to type design, which illustrated ways to construct, correct and space characters in a font. Then, the importance of type in branding was explained, as well as the various reasons why a brand might opt for a custom font, rather than a pre-existing one. This was demonstrated through various examples, as well as an exploration into IBM’s custom font, IBM Plex. In a case study, these concepts were put into practice, describing how a custom font was researched, designed and presented. A typeface, named Okra, con- sisting of uppercase characters, was built for a jewellery company and made to fit in with its brand and aesthetics. Custom fonts are meant to represent a brand whilst still functioning as type- faces. In the conclusion of this thesis, this was further elaborated, as Okra’s value in terms of branding was discussed in relation to its value as a typeface. This then led to an exploration on the merits and demerits of custom fonts, es- pecially in regard to smaller companies. Keywords: type design, typography, branding, custom font 3 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................5 -

TUGBOAT Volume 40, Number 2 / 2019 TUG 2019 Conference

TUGBOAT Volume 40, Number 2 / 2019 TUG 2019 Conference Proceedings TUG 2019 98 Conference sponsors, participants, program, photos 101 Henri Menke / Back to the roots: TUG 2019 in Palo Alto 104 Jennifer Claudio / TEX Users Group 2019 Annual General Meeting notes General Delivery 106 Jim Hefferon / What do today’s newcomers want? Software & Tools 108 Tomas Rokicki / Type 3 fonts and PDF search in dvips 112 Arthur Reutenauer / The state of X TE EX 113 Arthur Reutenauer / Hyphenation patterns: Licensing and stability 115 Richard Koch / MacTEX-2019, notification, and hardened runtimes 126 Uwe Ziegenhagen / Combining LATEX with Python 119 Didier Verna / Quickref: Common Lisp reference documentation as a stress test for Texinfo 129 Henri Menke / Parsing complex data formats in LuaTEX with LPEG Methods 136 William Adams / Design into 3D: A system for customizable project designs Electronic Documents 143 Martin Ruckert / The design of the HINT file format 147 Rishikesan Nair T., Rajagopal C.V., Radhakrishnan C.V. / TEXFolio — a framework to typeset XML documents using TEX 150 Aravind Rajendran, Rishikesan Nair T., Rajagopal C.V. / Neptune — a proofing framework for LATEX authors LATEX 153 Frank Mittelbach / The LATEX release workflow and the LATEX dev formats 157 Chris Rowley, Ulrike Fischer, Frank Mittelbach / Accessibility in the LATEX kernel — experiments in Tagged PDF 159 Boris Veytsman / Creating commented editions with LATEX—the commedit package 163 Uwe Ziegenhagen / Creating and automating exams with LATEX & friends Bibliographies 167 Sree -

The Fontspec Package Font Selection for X LE ATEX and Lualatex

The fontspec package Font selection for X LE ATEX and LuaLATEX WILL ROBERTSON With contributions by Khaled Hosny, Philipp Gesang, Joseph Wright, and others. http://wspr.io/fontspec/ 2020/02/21 v2.7i Contents I Getting started 5 1 History 5 2 Introduction 5 2.1 Acknowledgements ............................... 5 3 Package loading and options 6 3.1 Font encodings .................................. 6 3.2 Maths fonts adjustments ............................ 6 3.3 Configuration .................................. 6 3.4 Warnings ..................................... 6 4 Interaction with LATEX 2ε and other packages 7 4.1 Commands for old-style and lining numbers ................. 7 4.2 Italic small caps ................................. 7 4.3 Emphasis and nested emphasis ......................... 7 4.4 Strong emphasis ................................. 7 II General font selection 8 1 Main commands 8 2 Font selection 9 2.1 By font name ................................... 9 2.2 By file name ................................... 10 2.3 By custom file name using a .fontspec file . 11 2.4 Querying whether a font ‘exists’ ........................ 12 1 3 Commands to select font families 13 4 Commands to select single font faces 13 4.1 More control over font shape selection ..................... 14 4.2 Specifically choosing the NFSS family ...................... 15 4.3 Choosing additional NFSS font faces ....................... 16 4.4 Math(s) fonts ................................... 17 5 Miscellaneous font selecting details 18 III Selecting font features 19 1 Default settings 19 2 Working with the currently selected features 20 2.1 Priority of feature selection ........................... 21 3 Different features for different font shapes 21 4 Selecting fonts from TrueType Collections (TTC files) 23 5 Different features for different font sizes 23 6 Font independent options 24 6.1 Colour ..................................... -

Vizuální Styl Společnosti Puzzle

Vizuální styl společnosti Puzzle Petr Motl Bakalářská práce 2019 Univerzita Tomáše Bati ve Zlíně Cílem mé bakalářské práce je navrhnout vizuální jazyk společnosti Puzzle, která se zaměřuje na produkci digitálních služeb, jako tvorba Abstrakt webových stránek, online aplikací a hostingu. Teoretická část se zabývá průzkumem vizuální komunikace techno- logických společností, které seprimárně prezentují prostřednictvím svých digitálních produktů. Velkou část průzkumu věnuji kompara- tivní analýze design systémů, jazyků a stylů vybraných technologic- kých společností. Praktická část je zaměřena na tvorbu vizuálního stylu společnosti Puzzle po vzoru společností z mého průzkumu a tvorbě vizuálního jazyka uživatelských rozhraní digitálních produktů společnosti. The aim of my bachelor thesis is to design the visual language of Puzzle which focuses on the production of digital services such Abstract as website creation, online applications and hosting. The theoretical part deals with the research of visual communication of technological companies, which are primarily presented through their digital products. Much of the research is devoted to compara- tive analysis of the design of systems, languages and styles of selec- ted technology companies. The practical part is focused on creating the visual style of the com- pany Puzzle following the example of my research and creating the visual language of the user interface of digital products of the company. #design systém #vizuální jazyk #vizuální styl #Google #Microsoft #IBM #AirBnB #Uber #Dropbox #uživatelská rozhraní #knihovna komponent Poděkování Na tomto místě bych rád poděkoval všem, kteří mě doprovázeli během tvorby mé bakalářské práce a sdíleli se mnou čas, názory, důvěru i nadšení, a to především vedoucímu mé bakalářské práce MgA. Václavu Skácelovi, který mě svými nápady posunul k novým myšlenkám a možnostem uvažování. -

Beyond Trivial Counterfactual Generations with Diverse Valuable Explanations

Under review as a conference paper at ICLR 2021 BEYOND TRIVIAL COUNTERFACTUAL GENERATIONS WITH DIVERSE VALUABLE EXPLANATIONS Anonymous authors Paper under double-blind review ABSTRACT Explainability of machine learning models has gained considerable attention within our research community given the importance of deploying more reliable machine-learning systems. Explanability can also be helpful for model debugging. In computer vision applications, most methods explain models by displaying the regions in the input image that they focus on for their prediction, but it is dif- ficult to improve models based on these explanations since they do not indicate why the model fail. Counterfactual methods, on the other hand, indicate how to perturb the input to change the model prediction, providing details about the model’s decision-making. Unfortunately, current counterfactual methods make ambiguous interpretations as they combine multiple biases of the model and the data in a single counterfactual interpretation of the model’s decision. Moreover, these methods tend to generate trivial counterfactuals about the model’s decision, as they often suggest to exaggerate or remove the presence of the attribute be- ing classified. Trivial counterfactuals are usually not valuable, since the informa- tion they provide is often already known to the system’s designer. In this work, we propose a counterfactual method that learns a perturbation in a disentangled latent space that is constrained using a diversity-enforcing loss to uncover mul- tiple valuable explanations about the model’s prediction. Further, we introduce a mechanism to prevent the model from producing trivial explanations. Experi- ments on CelebA and Synbols demonstrate that our model improves the success rate of producing high-quality valuable explanations when compared to previous state-of-the-art methods. -

Download Full Essayactor-Network Versus Network

© 2019 Princeton University Press. The material is protected by copyright and its reproduction is restricted by law, except that you may download each available chapter and copy, redistribute the material in any medium or format for personal use, educational, and non-commercial purposes only, provided that you give appropriate credit to Princeton University Press. digitalSTS A Field Guide for Science & Technology Studies EDITED BY Janet Vertesi & David Ribes CO-EDITED BY Carl DiSalvo Laura Forlano Steven J. Jackson Yanni Loukissas Daniela K. Rosner Hanna Rose Shell PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS / PRINCETON & OXFORD © 2019 Princeton University Press. The material is protected by copyright and its reproduction is restricted by law, except that you may download each available chapter and copy, redistribute the material in any medium or format for personal use, educational, and non-commercial purposes only, provided that you give appropriate credit to Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to [email protected] Published by Princeton University Press 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved LCCN 2018955221 ISBN 978- 0- 691- 18707- 5 ISBN (pbk.) 978- 0- 691- 18708- 2 British Library Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available Editorial: Eric Crahan, Pamela Weidman, Kristin Zodrow Production Editorial: Terri O’Prey Production: Jacquie Poirier Publicity: Alyssa Sanford, Julia Hall Copyeditor: Joseph Dahm This book has been composed in IBM Plex Serif Printed on acid- free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2019 Princeton University Press. -

Pilcrows from Google Fonts.Pdf

True Reversed Pilcrows Arimo Cantarell Cardo EB Garamond Noto Sans Noto Serif ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ Nova Mono Roboto Roboto Condensed Tinos Vollkorn ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ ⁋ Mirrored Regular Pilcrows ABeeZee Abel Abhaya Libre Abril Fatface Aclonica Acme ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Actor Adamina Advent Pro Aguafina Script Akronim Aladin ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Alata Alatsi Aldrich Alegreya Alegreya Sans Aleo ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Alex Brush Alfa Slab One Alice Alike Alike Angular Allan ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Allura Almarai Almendra Almendra Display Almendra SC Amarante ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Amaranth Amatic SC Amethysta Amiko Amiri Amita ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Anaheim Andada Andika Annie Use Your Anonymous Pro Antic Telescope ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Antic Didone Antic Slab Anton Arapey Arbutus Arbutus Slab ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Architects Daughter Archivo Archivo Black Archivo Narrow Aref Ruqaa Arima Madurai ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Arizonia Armata Arsenal Artifika Arvo Arya ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Asap Asar Asset Assistant Astloch Asul ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Athiti Atma Atomic Age Aubrey Audiowide Autour One ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Average Average Sans Averia Gruesa Libre Averia Libre Averia Sans Libre Averia Serif Libre ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ B612 B612 Mono Bad Script Bahiana Bahianita Bai Jamjuree ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Baloo Baloo Bhai Baloo Bhaijaan ¶ Baloo Bhaina Baloo Chettan Baloo Da ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Baloo Paaji Baloo Tamma Baloo Tammudu Baloo Thambi Balthazar Bangers ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Barlow Barlow Condensed Barriecito ¶ Basic Baskervville Baumans ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Be Vietnam Bebas Neue Belgrano Bellefair Belleza BenchNine ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ Berkshire Swash Bevan Big Shoulders Display Big Shoulders Text Bigelow Rules Bigshot One ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ ¶ -

True Or False the Modernist Designers Believe That Helvetica Is a Wonderful Typeface

True or false the modernist designers believe that helvetica is a wonderful typeface Continue Other values are Helvetica(values). 1957 sans-serif typeface created by Max Miedinger HelveticaCategorySans-serifClassificationNeo-grotesque sans-serif[1]Designer(s)Max Miedinger, Eduard HoffmannFoundryHaas Type FoundryDate released1957Re-issuing foundryMergenthaler Linotype CompanyDesign basedAkenzzid GroteskVariationsHelvetica InseratHelvetica CompressedNeue HelveticaHelvetica Nowothers (see Annex II). Also known as Neue Haas Grotesk Helvetica or Neue Haas Grotesk is widely used sans-serif typeface created in 1957 by Swiss font designer Max Miedinger with input from Eduard Hmannoff. Helvetica is a neo-grotesque design, one influenced by the famous 19th century font Akzidenz-Grotesk and other German and Swiss designs. [2] Its use has become a feature of the international typographical style, which originated from the work of Swiss designers in the 1950s and 60s, becoming one of the most popular fonts of the 20th century. [3] Over the years, various variants have been released, with different weight, width and sizes, as well as non-Latin alphabet designs. The memorable features of Helvetica, as originally developed, are high x height, the cessation of strokes in horizontal or vertical lines and an unusually close space between the letters that connect to give it a dense, firm appearance. Developed by Haas'sche Schriftgiesserei (Haas Type Foundry) in Münchenstein, Switzerland, its release was planned to match the trend: interest in turn-of-the-century grotesque sans-serifs among European graphic designers that also saw the release of Univers by Adrian Frutiger in the same year. [4] Hoffmann was president of Haas Type Foundry, while Miedinger was a freelance graphic designer who previously worked as a Haas salesman and designer. -

In Kepler's Gardens

In Kepler’s Gardens A global journey mapping the ‘new’ world Edited by Gerfried Stocker / Christine Schöpf / Hannes Leopoldseder Ars Electronica 2020 Festival for Art, Technology, and Society September 9 — 13, 2020 Ars Electronica, Linz Editors: Hannes Leopoldseder, Christine Schöpf, Gerfried Stocker Editing: Veronika Liebl, Anna Grubauer, Maria Koller, Alexander Wöran Translations: German — English: Douglas Deitemyer, Daniel Benedek Copyediting: Laura Freeburn, Mónica Belevan Graphic design and production: Main layout: Cornelia Prokop, Lunart Werbeagentur Cover: Gerhard Kirchschläger Minion Typeface: IBM Plex Sans PEFC Certified This product is from Printed by: Gutenberg-Werbering Gesellschaft m.b.H., Linz sustainably managed forests and controlled sources Paper: MagnoEN Bulk 1,1 Vol., 115 g/m², 300 g/m² www.pefc.org PEFC Certified © 2020 Ars Electronica PEFC Certified PEFC Certified This product is This product is This product is PEFC Certified © 2020 for the reproduced works by the artists, from sustainably from sustainably from sustainably This product is from managed forests or their legal successors managed forests managed forests sustainably managed and controlled and controlled and controlled forests and controlled sources Published by sources sources sources Hatje Cantz Verlag www.pefc.org www.pefc.org www.pefc.org www.pefc.org Mommsenstrasse 27 10629 Berlin PEFC Certified Germany This product is from www.hatjecantz.com sustainably managed forests and controlled A Ganske Publishing Group company sources www.pefc.org Hatje Cantz