Medical Readiness of the Reserve Component

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense Primer: Reserve Forces

Updated January 28, 2021 Defense Primer: Reserve Forces The term reserve component (RC) refers collectively to the passes from the governor of the affected units and seven individual reserve components of the Armed Forces. personnel to the President of the United States. Congress exercises authority over the reserve components under its constitutional authority “to raise and support Reserve Categories Armies,” “to provide and maintain a Navy,” and “to All reservists, whether they are in the Reserves or the provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the National Guard, are assigned to one of three major reserve Militia.... ” (Article I, Section 8) categories: the Ready Reserve, the Standby Reserve, or the Retired Reserve. There are seven reserve components: Ready Reserve Army National Guard The Ready Reserve is the primary manpower pool of the reserve components. Members of the Ready Reserve will Army Reserve usually be called to active duty before members of the Standby Reserve or the Retired Reserve. The Ready Navy Reserve Reserve is made up of three subcomponents: Marine Corps Reserve The Selected Reserve contains those units and individuals within the Ready Reserve designated as “so Air National Guard essential to initial wartime missions that they have priority over all other Reserves.” (DOD Instruction Air Force Reserve 1215.06.) Members of the Selected Reserve are generally required to perform one weekend of training Coast Guard Reserve each month and two weeks of training each year, although some may train more than this. When The purpose of these seven reserve components, as codified reservists are activated, they most frequently come from in law, is to “provide trained units and qualified persons this category. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

Officer Candidate Guide US Army National Guard

Officer Candidate Guide May 2011 Officer Candidate Guide US Army National Guard May 2011 Officer Candidate Guide May 2011 Officer Candidate School, Reserve Component Summary. This pamphlet provides a guide for US Army National Guard Officer Candidate School students and cadre. Proponent and exception authority. The proponent of this pamphlet is the Commanding General, US Army Infantry School. The CG, USAIS has the authority to approve exceptions to this pamphlet that are consistent with controlling laws and regulations. The CG, USAIS may delegate this authority, in writing, to a division chief within the proponent agency in the grade of Colonel or the civilian equivalent. Intent. The intent of this pamphlet is to ensure that National Guard OCS Candidates nationwide share one common standard. It facilitates the cross-state and cross-TASS region boundary training of US Army officer candidates. Use of the term “States”. Unless otherwise stated, whenever the term “States” is used, it is referring to the CONUS States, Alaska, Hawaii, the US Virgin Islands, Territory of Guam, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and District of Columbia. Supplementation. Local OCS programs may supplement this document in order to meet the needs of local SOPs and regulations, but they may not substantially modify any policy set forth in this document without written authorization from the proponent. Suggested improvements. Users are invited to send comments and suggested improvements on DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms) directly to the OCS SME, 200th Regiment, Fort McClellan, Alabama 36205. Distribution. This publication is available in electronic media only and is intended for all Reserve Component OCS cadre and students. -

Main Command Post-Operational Detachments

C O R P O R A T I O N Main Command Post- Operational Detachments (MCP-ODs) and Division Headquarters Readiness Stephen Dalzell, Christopher M. Schnaubelt, Michael E. Linick, Timothy R. Gulden, Lisa Pelled Colabella, Susan G. Straus, James Sladden, Rebecca Jensen, Matthew Olson, Amy Grace Donohue, Jaime L. Hastings, Hilary A. Reininger, Penelope Speed For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2615 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0225-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled Multi- Component Units and Division Headquarters Readiness sponsored by U.S. -

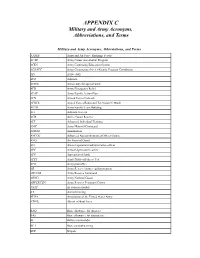

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Michigan Army National Guard Soldiers Continue Operations in Houghton County

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE News Release No. 16 – June 27, 2018 Michigan Army National Guard Soldiers Continue Operations in Houghton County LANSING, MICH. The Michigan National Guard remains in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula assisting with repair operations following severe rain that caused extensive washouts. The deployment has been extended to Tuesday, July 3, to help with projects to make the roads passable. Approximately 70 Soldiers from armories in Kingsford, Iron River, Calumet, Sault Ste. Marie and Montague were activated in response to the emergency declaration issued by Governor Snyder June 18. The Soldiers are members of 107th Engineer Battalion headquartered in Ishpeming and the 507th Engineer Battalion headquartered in Kalamazoo. The Soldiers have been moving gravel to repair affected areas. The temporary repairs allow stranded residents avenues of entry and exit that have been destroyed by the floodwaters; also improving the public health capabilities allowing for passage by emergency medical services. “Our Soldiers have made progress, but more work needs to be done. They stand ready to help and remain committed to completing their mission,” said Maj. Gen. Greg Vadnais, adjutant general of the Michigan National Guard and director of the Michigan Department of Military and Veterans Affairs. “The men and women I work with never fail to impress me. I hope we have been able to provide comfort to our Michigan residents who will be dealing with the aftermath of this destructive flooding for quite some time.” About the Michigan National Guard The Michigan National Guard’s 10,000 Soldiers and Airmen stand ready to serve both state and nation. -

1 January 2000 TARNRG 600-8-22

1 January 2000 TARNRG 600-8-22 DECORATIONS, AWARDS AND HONORS of the Tennessee Army National Guard CHAPTER 1 GENERAL 1-1. Purpose. This regulation is established to prescribe the decorations and awards for service which has been performed in the Tennessee Army National Guard. 1-2. Scope. This regulation applies only to decorations, awards, and honors presented by the Tennessee Army National Guard. Tennessee Air National Guard (TNANG) decorations and awards policy is published in a separate TNANG regulation 1-3. Federal Awards. Awards which may be awarded to National Guard members, if they meet the criteria, are shown with the applicable paragraph from AR 600-8-22. a. Medals. Award of federal medal may be made in peacetime by the Secretary of Defense or Secretary of the Army to members of the Reserve Components of the Army who are not in active federal military service. Service medals that require presence in a specific theater or war for award are not listed. These can be found in AR 600-8-22. (1) Active Component Approval. Award of these medals requires submission of DA Form 638 and accompanying justification for approval through HQ, Tennessee Army National Guard, STARC (-), ATTN: AGTN-DPER (with letter of transmittal), through HQ, Second Army to HQ, Forces Command (FORSCOM) or HQDA. AR 600-8-22 Para 3.8 DISTINGUISHED SERVICE MEDAL (DSM) For any member who has distinguished himself by exceptionally meritorious service to the Government in a duty of great responsibility. Not for exceptional performance of normal duty. AR 600-8-22 Para 2.4 DEFENSE SUPERIOR SERVICE MEDAL (DSSM) For assignment to joint staffs and other joint activities of the Department of Defense, while in a position of significant responsibility has rendered superior meritorious service. -

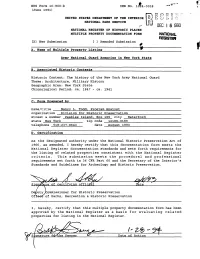

Z-Fe - 9F Date of Action ARMY NATIONAL GUARD ARMORIES in NEW YORK STATE

f" NFS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (June 1991) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE t.* * DEC I 6 1993 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES MULTIPLE PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION FORM NATIONAL REGISTER [X] New Submission [ ] Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Army National Guard Armories in New York State B. Associated Historic Contexts Historic Context: The history of the New York Army National Guard Theme: Architecture, Military History Geographic Area: New York State Chronological Period: ca. 1847 - ca. 1941 C. Form Prepared by name/title Nancy L. Todd, Program Analyst organization Division for Historic Preservation street & number Peebles Island, Box 189 city Waterford state New York____________ zip code 12188-0189 telephone 518-237-8643 date August 1993 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. &&s Si re of certifying office Date DeputyyCommissioner for Historic Preservation Oftiee of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. Z-fe - 9f Date of Action ARMY NATIONAL GUARD ARMORIES IN NEW YORK STATE Table of Contents for Written Narrative E. -

December 2007 Kansans Donate Thousands to Bring Troops Home for Christmas by Sharon Watson Home for Christmas in December 2003, Kansas Gov

35th ID Eight months “Care pack- assumes later, town is ages” warm control in on its way the hearts of PPllKosovoaaii . n.n . .2 ss GGbackuu . .a a. .11rrddiiSoldiersaann . .15 Volume 50 No. 6 Serving the Kansas Army and Air National Guard, Kansas Emergency Management, Kansas Homeland Security and Civil Air Patrol December 2007 Kansans donate thousands to bring troops home for Christmas By Sharon Watson home for Christmas in December 2003, Kansas Gov. Kathleen Sebelius and then died in May 2004. To her we say announced Friday, Dec. 7, that more than a special heartfelt ‘thank you,’ and to $135,000 in cash donations was raised since everyone, thank you so much for what you Dec. 3 to bring approximately 430 Kansas have done to bring our troops home,” National Guard troops home for Christmas. Sebelius said. “There is no doubt Kansans An additional $14,000 was raised from in- care deeply about our Soldiers and this is a kind contributions. The funds were donated small way to thank them and their families primarily to the Kansas National Guard for their service and sacrifice.” Foundation and also to the 161st Field The lead corporate givers, Wal-Mart Artillery Regimental Association. Stores and Koch Industries, Inc., donated The 1st Battalion, 161st Field Artillery more than $40,000. Wal-Mart presented a is training in Fort Bliss, Texas, for a late check to the Kansas National Guard winter deployment to Iraq, and many Foundation for $21,225 and Koch Guardsmen didn’t have the funds to get Industries, Inc. presented a $20,000 check. -

Kansas Army National Guard Officer Position Book

KANSAS ARMY NATIONAL GUARD OFFICER POSITION BOOK Fiscal Year 2021 Updated 01 November 2020 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………… 4 KSARNG Officer Position Roll-up ........................................................................ 5 Operations Division (OD) Air Defense Artillery (AD) (14A) ......................................................................... 7 Armor (19A) .................................................................................................... 11 Aviation Corps (15A, 15B, 15D, 67J Series) ................................................... 15 Chemical Corps (CM) (74A) ............................................................................ 19 Civil Affairs (CA) (38A) .................................................................................... 23 Corps of Engineers (EN) (12A) ....................................................................... 27 Field Artillery (FA) (13A) .................................................................................. 31 Infantry (IN) (11A) ........................................................................................... 37 Military Police (MP) (31A) ............................................................................... 41 Psychological Operations (PO) (37A) ............................................................. 45 Operations Support Division (OSD) Force Management (FD) (50A) ....................................................................... 49 Information Networks Engineering (SE) (26B) ................................................ -

Final Armory Historic Context

FINAL ARMORY HISTORIC CONTEXT ARMY NATIONAL GUARD NATIONAL GUARD BUREAU June 2008 FINAL HISTORIC CONTEXT STUDY Prepared for: Army National Guard Washington, DC Prepared by: Burns & McDonnell Engineering Company, Inc Engineers-Architects-Consultants Kansas City, Missouri And Architectural and Historical Research, LLC Kansas City, Missouri Below is the Disclaimer which accompanied the historic context when submitted to the NGB in draft form in 2005. Due to reorganization of the document prior to its finalization, the section in which Burns & McDonnell references below has been changed and is now Section II of the document, which is written in its entirety by Ms. Renee Hilton, Historical Services Division, Office of Public Affairs &Strategic Communications, National Guard Bureau. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND, AND METHODOLOGY ........................... 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 BACKGROUND............................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 SURVEY BOUNDARIES AND RESOURCES ............................................... 1-2 1.4 SURVEY OBJECTIVES................................................................................. 1-2 1.5 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 1-3 1.6 REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS.............................................................. 1-4 1.7 HISTORIC INTEGRITY ................................................................................ -

A History of the Bellingham National Guard Armory 525 N

A HISTORY OF THE BELLINGHAM NATIONAL GUARD ARMORY 525 N. State Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 By Taylor Russell All pictures courtesy of the Whatcom Museum’s Photo Archives For thousands of years, the area surrounding Bellingham Bay was inhabited by the Coast Salish people. Local tribes such as the Lummi Indians made use of the natural waterways and abundant resources, like trees and fish. In the early 19th century, Euro-American settlers were attracted to these same resources and the Bay’s convenient location between the burgeoning metropolises of Vancouver, Victoria, and Seattle. The first permanent settlers, Captains Henry Roeder and Russell Peabody, arrived in December 1852 and opened a mill at Whatcom Creek. The environment and demographics rapidly changed as more mills and lumberyards, mines, and fish canneries sprouted along the shore, serviced by well- connected trade and transportation networks. Four separate towns developed around the bay, fueled in part by the miners, settlers, and entrepreneurs en route to the Fraser Canyon goldfields in nearby British Columbia. As more and more settlers flooded the Puget Sound area, Coast Salish people, many travelling from distant Canadian and Russian territories, frequently attacked the new town sites, disrupting Euro-Americans’ industries. This motivated the United States government to build military strongholds in the Northwest to protect the many settlements, like those at Port Townsend, Whidbey Island, and Bellingham Bay, from Indian attacks. In 1856, the US Army sent Captain George Pickett to build Fort Bellingham to defend the resources and Fort Bellingham, built in 1856. developing towns on the bay. The fort would be the first instance of a national military presence in the Bellingham area.