Download (1541Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surviving the Holocaust: Jean Améry and Primo Levi

Surviving the Holocaust: Jean Améry and Primo Levi by Livia Pavelescu A thesis submitted to the Department of German Language and Literature in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August 2000 Copyright OLivia Pavelescu, 2000 National Li'brary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada uisitions and Acquisitions et 9-&b iographi Senrices services bibliographiques 395 wtmlgm Street 395. Ne WeUington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON KfAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distri'buer ou copies of îhis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/fiIm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantîal extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This study is predicated on the assumption that there is a culture of the Holocaust in Austria and Itaiy and that its strongest manifestation is the literahire of the Holocaust. The purpose of this thesis is twofold. First it detemiines a representative spectnun of reaction to the Holocaust by using two texts Se questo è un uomo (Sumival in Auschwitz) and Jemeits von Schuld und Sühne (At the MNld'S Limits) of two prominent writen, Primo Levi and Jean Améry. -

Bollettino Novità

Bollettino Novità Biblioteca del Centro Culturale Polifunzionale "Gino Baratta" di Mantova 4' trimestre 2019 Biblioteca del Centro Culturale Polifunzionale "Gino Baratta" Bollettino novità 4' trimestre 2019 1 Le *100 bandiere che raccontano il mondo / DVD 3 Tim Marshall ; traduzione di Roberto Merlini. - Milano : Garzanti, 2019. - 298 p., [8] carte 3 The *100. La seconda stagione completa / di tav. : ill. ; 23 cm [creato da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : inv. 178447 Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia, 2016. - 4 DVD-Video (ca. 674 min. compless.) -.929.9209.MAR.TIM color., sonoro ; in contenitore, 19 cm. 1 v ((Caratteristiche tecniche: regione 2; 16:9 FF, adatto a ogni tipo di televisore; audio 2 The *100. La prima stagione completa / Dolby digital 5.1. - Titolo del contenitore. [creato da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : - Produzione televisiva USA 2014-2015. - Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia, 2014. Interpreti: Eliza Taylor, Bob Morley, Marie - 3 DVD-Video (circa 522 min) : Avgeropoulos. - Lingue: italiano, inglese; color., sonoro ; in contenitore, 19 cm. sottotitoli: italiano, inglese per non udenti ((Caratteristiche tecniche: regione 2; video + 1: The *100. 2. : episodi 1-4 / [creato 16:9, 1.85:1 adatto a ogni tipo di tv; da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : Warner audio Dolby digital 5.1, 2.0. - Titolo Bros. entertainment Italia, 2016. - 1 DVD- del contenitore. - Prima stagione in Video (ca. 172 min.) ; in contenitore, 13 episodi del 2014 della serie TV, 19 cm. ((Contiene: I 48 ; Una scoperta produzione USA. - Interpreti: Eliza Taylor, agghiacciante ; Oltre lapaura ; Verso la città Isaiah Washington, Thomas McDonell. - della luce. Lingue: italiano, inglese, francese, tedesco; inv. 180041 sottotitoli: italiano, inglese, tedesco per non udenti, inglese per non udenti, tedesco, DVFIC.HUNDR.1 francese, olandese, greco DVD 1 + 1: The *100'. -

Secrets and Bombs: the Piazza Fontana Bombing and the Strategy of Tension - Luciano Lanza

Secrets and Bombs: The Piazza Fontana bombing and the Strategy of Tension - Luciano Lanza Secrets and Bombs 21: TIMETABLE – A Basic Chronology (with video links) January 29, 2012 // 1 2 Votes Gladio (Italian section of the Clandestine Planning Committee (CPC), founded in 1951 and overseen by SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers, Europe) 1969 25 April — Two bombs explode in Milan: one at the FIAT stand at the Trade Fair and another at the bureau de change in the Banca Nazionale delle Communicazione at Central Station. Dozens are injured but none seriously. AnarchistsEliane Vincileone, Giovanni Corradini, Paolo Braschi,Paolo Faccioli, Angelo Piero Della Savia and Tito Pulsinelliare arrested soon after. 2 July — Unified Socialist Party (PSU), created out of an amalgamation of the PSI and the PSDI on 30 October 1966, splits into the PSI and the PSU. 5 July — Crisis in the three-party coalition government (DC, PSU and PRI) led by Mariano Rumor. 5 August — Rumor takes the helm of a single party (DC — Christian Democrat) government. 9 August — Ten bombs planted on as many trains. Eight explode and 12 people are injured. 7 December — Corradini and Vincileone are released from jail for lack of evidence. Gladio 12 December — Four bombs explode. One planted in the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in the Piazza Fontana in Milan claims 16 lives and wounds a further hundred people. In Rome a bomb explodes in the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, wounding 14, and two devices go off at the cenotaph in the Piazza Venezia, wounding 4. Another bomb — unexploded — is discovered at the Banca Commerciale in the Piazza della Scala in Milan. -

IHF REPORT 2006 ITALY 213 Reduce the Number of Applications Against Judges and Prosecutors Among Magis- Italy in the Ecthr

ITALY* 211 IHF FOCUS: freedom of expression and free media; judicial system and the right to a fair trial; ill-treatment and police misconduct; prisons; freedom of religion and re- ligious tolerance; migrants and asylum seekers; ethnic minorities (Roma). Excessive length of court proceedings 90% of all television revenues and audi- and overcrowding in prisons remained ences in Italy were controlled by the pri- among the most serious human rights vately owned company “Mediaset” and by problems in Italy. the public broadcaster RAI. “Fininvest,” a Waves of illegal immigrants continued holding company owned by Prime Minister to arrive in the country, creating problems Silvio Berlusconi’s family, is a major share- in the provision of temporary assistance, holder in “Mediaset,” and Berlusconi indi- the fight against human trafficking, and so- rectly controls also many other media cial integration, and which were followed companies, including the “Mondadori” by mass expulsions. Asylum seekers, al- publishing group, two daily newspapers, though protected by the constitution, were and several weekly publications. The OSCE not covered by specific legislation to im- representative stated that in a democracy, plement the right to asylum. it is incompatible to be both in charge of Freedom of expression and media news media and to hold a public post, freedom, which were generally protected, pointing out that such a link results in con- were still affected by media concentration flicts between political and business inter- and by the fact that defamation through ests in the shaping of public opinion.2 the press remained a criminal offence. Under the 2004 “Gasparri Act,”3 a me- The serious problems faced by the dia group may now control more than Italian judicial system were reflected by the 20% of television or print media, provided fact that Italy had the fifth highest number that its share of the total market is less of applications to the European Court of than 20%. -

00A Inside Cover CC

Access Provided by University of Manchester at 08/14/11 9:17PM GMT 05 Thoburn_CC #78 7/15/2011 10:59 Page 119 TO CONQUER THE ANONYMOUS AUTHORSHIP AND MYTH IN THE WU MING FOUNDATION Nicholas Thoburn It is said that Mao never forgave Khrushchev for his 1956 “Secret Speech” on the crimes of the Stalin era (Li, 115–16). Of the aspects of the speech that were damaging to Mao, the most troubling was no doubt Khrushchev’s attack on the “cult of personality” (7), not only in Stalin’s example, but in principle, as a “perversion” of Marxism. As Alain Badiou has remarked, the cult of personality was something of an “invariant feature of communist states and parties,” one that was brought to a point of “paroxysm” in China’s Cultural Revolution (505). It should hence not surprise us that Mao responded in 1958 with a defense of the axiom as properly communist. In delineating “correct” and “incorrect” kinds of personality cult, Mao insisted: “The ques- tion at issue is not whether or not there should be a cult of the indi- vidual, but rather whether or not the individual concerned represents the truth. If he does, then he should be revered” (99–100). Not unex- pectedly, Marx, Engels, Lenin, and “the correct side of Stalin” are Mao’s given examples of leaders that should be “revere[d] for ever” (38). Marx himself, however, was somewhat hostile to such practice, a point Khrushchev sought to stress in quoting from Marx’s November 1877 letter to Wilhelm Blos: “From my antipathy to any cult of the individ - ual, I never made public during the existence of the International the numerous addresses from various countries which recognized my merits and which annoyed me. -

Society for Italian Studies Biennial Conference 2019

Society for Italian Studies Biennial Conference 2019 University of Edinburgh 26-28 June 2019 Programme Welcome Benvenute! Benvenuti! Italian Studies at the University of Edinburgh are truly delighted to welcome you all to the 2019 Biennial Conference of the Society for Italian Studies. We are celebrating the Centenary of Italian at the University of Edinburgh (1919-2019), and we are proud to be hosting this major conference with nearly 300 delegates, including some of the most distinguished keynote speakers, leading academics, and inspiring students from Europe, Australia, North America and beyond. Thank you for your participation. Enjoy the Conference! The Edinburgh Team Edinburgh Team The Edinburgh team consists of staf and students of the University of Edinburgh. Lead Organisers Davide Messina Federica G Pedriali Co-Organisers Nicolò Maldina Carlo Pirozzi Information Desk Marco Palone Daniela Sannino Marialaura Aghelu Helpers Simone Calabrò Daniele Falcioni Niamh Keenan Alessandra Pellegrini De Luca Marco Ruggieri University of Ediburgh School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures Department of European Languages & Cultures 50 George Square Edinburgh EH8 9LH www.llc.ed.ac.uk/delc/italian/sis-2019 For further information, please email the Lead Organisers Davide Messina ([email protected]) and Federica G. Pedriali ([email protected]) Keynote Lectures On Ulysses: in Praise The Changing Fortunes Speaking in Cultures of Literature of Translations Wednesday 26 June Wednesday 26 June Wednesday 26 June 11:00-12:00, Room G.03 1:00-2:00, Room G.03 6:15-6:50, Scottish Parliament Lino Pertile is Carl A. Susan Bassnett is Professor Jhumpa Lahiri is Professor Pescosolido Research of Comparative Literature at of Creative Writing at the Professor of Romance the University of Glasgow, Lewis Center for the Arts, Languages and Literatures, and Professor Emerita of Princeton. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

Dalle Pagine Al Quaderno

Dalle pagine al quaderno. Cinque anni di “Pagina che non c’era” a cura di Raffaella Bosso ISBN 978-88-96583-94-4 © 2016, Edizioni Arcoiris, Salerno Prima edizione marzo 2016 www.edizioniarcoiris.it Questo volume è pubblicato grazie al sostegno del Forum Internazionale delle Culture di Napoli 2013 Logo in copertina di Cyop&Kaf Riservati tutti i diritti. È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale e con qualsiasi mezzo, se non attraverso l’autorizzazione scritta da parte dell’autore e/o dell’editore. Dalle pagine al quaderno cinque anni di “Pagina che non c’era” a cura di Raffaella Bosso Il nonno di Sartre (o scrivere come leggere) Nel 1964 Jean-Paul Sartre pubblica Les mots, una narrazione auto- biografica della propria infanzia di lettore e di scrittore. Il libro, immediatamente tradotto in italiano da Luigi De Nardis con il titolo Le parole (Il Saggiatore 1964), è diviso in due parti: Leggere e Scrivere, le due distinte azioni – “imposture” le definisce lo stesso autore – attraverso le quali l’uomo tenta di prendere possesso del linguaggio, rimanendo allo stesso tempo, in qualche modo, suo prigioniero. “Ho cominciato la mia vita – scrive Jean-Paul all’età di cin- quantanove anni – come senza dubbio la terminerò: tra i libri”. E in mezzo ai libri, circondato dall’affetto di lettori e scrittori, co- mincia la passione per la letteratura di Sartre, fin da bambino intento a immergersi nelle storie, immedesimandosi nei perso- naggi e nei narratori fino al punto da avere terrore “dell’acqua, dei granchi e degli alberi” dopo la lettura dell’almanacco illustrato Hachette. -

Gianni Celati' S Le Avventure Di Guizzardi, La Banda De; Sospiri and Lunario Dei Paradiso

Developing a Poetics of Ordinariness: Language, Literature and Communication in Gianni Celati' s Le avventure di Guizzardi, La banda de; sospiri and Lunario dei paradiso Monica Powers Department of Italian Studies, McGill University, Montreal September 2005 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Monica Powers, 2005 Library and Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24912-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-24912-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell th es es le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Characterising the Anthropocene: Ecological Degradation in Italian Twenty-First Century Literary Writing

Characterising the Anthropocene: Ecological Degradation in Italian Twenty-First Century Literary Writing by Alessandro Macilenti A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Literature. Victoria University of Wellington 2015 Abstract The twenty-first century has witnessed the exacerbation of ecological issues that began to manifest themselves in the mid-twentieth century. It has become increasingly clear that the current environmental crisis poses an unprecedented existential threat to civilization as well as to Homo sapiens itself. Whereas the physical and social sciences have been defining the now inevitable transition to a different (and more inhospitable) Earth, the humanities have yet to assert their role as a transformative force within the context of global environmental change. Turning abstract issues into narrative form, literary writing can increase awareness of environmental issues as well as have a deep emotive influence on its readership. To showcase this type of writing as well as the methodological frameworks that best highlights the social and ethical relevance of such texts alongside their literary value, I have selected the following twenty-first century Italian literary works: Roberto Saviano’s Gomorra, Kai Zen’s Delta blues, Wu Ming’s Previsioni del tempo, Simona Vinci’s Rovina, Giancarlo di Cataldo’s Fuoco!, Laura Pugno’s Sirene, and Alessandra Montrucchio’s E poi la sete, all published between 2006 and 2011. The main goal of this study is to demonstrate how these works offer an invaluable opportunity to communicate meaningfully and accessibly the discomforting truths of global environmental change, including ecomafia, waste trafficking, illegal building, arson, ozone depletion, global warming and the dysfunctional relationship between humanity and the biosphere. -

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel

Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel, Edited by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Madelena Gonzalez and Marie-Odile Pittin-Hédon and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-1732-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-1732-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Madelena Gonzalez ................................................................................... vii Chapter One Generic Instability and the Limits of Postcolonial Identity Crossing Borders and Transforming Genres: Alain Robbe-Grillet, Edward Saïd, and Jamaica Kincaid Linda Lang-Peralta ...................................................................................... 2 Reading Nara’s Diary or the Deluding Strategies of the Implied Author in The Rift Marie-Anne Visoi...................................................................................... 11 Contaminated Copies: J.M.Coetzee’s -

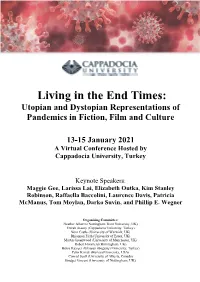

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries.