Primo Levi's “Small Differences” and the Art of the Periodic Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surviving the Holocaust: Jean Améry and Primo Levi

Surviving the Holocaust: Jean Améry and Primo Levi by Livia Pavelescu A thesis submitted to the Department of German Language and Literature in confonnity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August 2000 Copyright OLivia Pavelescu, 2000 National Li'brary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada uisitions and Acquisitions et 9-&b iographi Senrices services bibliographiques 395 wtmlgm Street 395. Ne WeUington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON KfAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distri'buer ou copies of îhis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/fiIm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantîal extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This study is predicated on the assumption that there is a culture of the Holocaust in Austria and Itaiy and that its strongest manifestation is the literahire of the Holocaust. The purpose of this thesis is twofold. First it detemiines a representative spectnun of reaction to the Holocaust by using two texts Se questo è un uomo (Sumival in Auschwitz) and Jemeits von Schuld und Sühne (At the MNld'S Limits) of two prominent writen, Primo Levi and Jean Améry. -

Rethinking Primo Levi

Rethinking Primo Levi Primo Levi’s influence in the field of Holocaust studies cannot be underestimated, and the Ottawa conference provides an excellent opportunity to take stock of the effects. From Survival in Auschwitz (1947; 1958) to The Drowned and the Saved (1986), Levi’s writings have become authoritative canonical works of Holocaust literature, providing consistent reference points in our attempts to understand the Nazi camps. Levi’s acerbic account of the Dante-esque descent of the innocent to “the bottom”; his unflinching anatomy of that swift and brutal transformation he calls “the demolition of a man”; and his iteration of the first lesson of Auschwitz—“here there is no why”—have profoundly affected Holocaust scholarship. Indeed, terms and concepts in his work have provided scholars with a number of paradigms. These include the “gray zone,” Levi’s term for the range of compromised human behavior in the camp; Levi’s claim that “if the Lagers had lasted longer a new, harsh language would have been born, ”given that “free words” fail to account for the devastation of camp internment and torture; and his portrayal of “the Muselmänner” as the mute living dead—the “complete witnesses,” who cannot testify and in whose stead the survivors must therefore speak. Seeking to rethink such paradigmatic uses of Levi, this panel focuses on Levi as a writer and author of significant Holocaust texts, but also as a scientist; a writer of science fiction; a sexual being questioning his manhood; and a recorder and critic of the human condition broadly. Following Berel Lang’s 2013 biography of Levi, which proposes that we see Levi’s life as a series of tensions, we probe the“divided road” between his life as a pre-war scientist and a post-war writer; his personal and more global moral commitments; and his ambivalent feelings about his own Jewishness. -

Homage to Alberto Moravia: in Conversation with Dacia Maraini At

For immediate release Subject : Homage to Alberto Moravia: in conversation with Dacia Maraini At: the Italian Cultural Institute , 39 Belgrave Square, London SW1X 8NX Date: 26th October 2007 Time: 6.30 pm Entrance fee £5.00, booking essential More information : Press Officer: Stefania Bochicchio direct line 0207 396 4402 Email [email protected] The Italian Cultural Institute in London is proud to host an evening of celebration of the writings of Alberto Moravia with the celebrated Italian writer Dacia Maraini in conversation with Sharon Wood. David Morante will read extracts from Moravia’s works. Alberto Moravia , born Alberto Pincherle , (November 28, 1907 – September 26, 1990) was one of the leading Italian novelists of the twentieth century whose novels explore matters of modern sexuality, social alienation, and existentialism. or his anti-fascist novel Il Conformista ( The Conformist ), the basis for the film The Conformist (1970) by Bernardo Bertolucci; other novels of his translated to the cinema are Il Disprezzo ( A Ghost at Noon or Contempt ) filmed by Jean-Luc Godard as Le Mépris ( Contempt ) (1963), and La Ciociara filmed by Vittorio de Sica as Two Women (1960). In 1960, he published one of his most famous novels, La noia ( The Empty Canvas ), the story of the troubled sexual relationship between a young, rich painter striving to find sense in his life and an easygoing girl, in Rome. It won the Viareggio Prize and was filmed by Damiano Damiani in 1962. An adaptation of the book is the basis of Cedric Kahn's the film L'ennui ("The Ennui") (1998). In 1960, Vittorio De Sica cinematically adapted La ciociara with Sophia Loren; Jean- Luc Godard filmed Il disprezzo ( Contempt ) (1963); and Francesco Maselli filmed Gli indifferenti (1964). -

Production, Myth and Misprision in Early Holocaust Cinema “L’Ebreo Errante” (Goffredo Alessandrini, 1948)

Robert S. C. Gordon Production, Myth and Misprision in Early Holocaust Cinema “L’ebreo errante” (Goffredo Alessandrini, 1948) Abstract This essay examines the production, style and narrative mode of a highly significant, if until recently largely forgotten early Italian Holocaust film, Goffredo Alessandrini’s “L’ebreo errante” (“The Wandering Jew”, 1948), starring a young Vittorio Gassman and Valentina Cortese. The film is analysed as a hybrid work, through its production history in the disrupted setting of the post-war Roman film industry, through its aesthetics, and through its bold, although often incoherent attempts to address the emerging history of the concentration camps and the genocide of Europe’s Jews. Emphasis is placed on its very incoherence, its blindspots, clichés and contradictions, as well as on its occasionally sophisticated genre touches, and confident stylistic and formal tropes. These aspects are read together as powerfully emblematic of Italy’s confusions in the 1940s over its recent history and responsibilities for Fascism, the war and the Holocaust, and of the potential for cinema to address these profound historical questions. In the immediate months and years following liberation and the end of the war in 1945, the Italian film industry went through a period of instability, transition and reconstruc- tion just like the rest of the country, devastated and destabilized as it had been by the wars and civil wars since 1940, not to speak of more than two decades of dictatorship. 1 In parallel with the periodization of national politics, where the transition is conventionally seen as coming to an end with the bitterly fought parliamentary elections of April 1948, the post-war instability of the film industry can be given a terminus a quo at the emblem- atic re-opening of the Cinecittà film studios in Rome in 1948, following several years of 1 On the post-war film industry, cf. -

The Other in the Works of Giorgio Bassani

21. TRANSITIONAL IDENTITIES The Other in the Works of Giorgio Bassani Cristina M. Bettin The outcast is a central theme in Bassani’s narrative, which is set mainly in Ferrara, the small city in northern Italy where Bassani grew up. Fer- rara played a crucial role in Bassani’s work, as he explained in a 1979 interview: Io torno a Ferrara, sempre, nella mia narrativa, nello spazio e nel tempo: il ritorno a Ferrara, il recupero di Ferrara per un romanziere del mio tipo è necessario, ineliminabile, dovevo fare i conti con le mie radici, come fa sem- pre ogni autore, ogni poeta. Ma questo «ritorno», questo «recupero», ho dovuto cercare di meritarmelo davanti a chi legge, per questo motivo il recu- pero di Ferrara non avviene in modo irrazionale, proustiano, sull’onda dei ricordi, ma fornendo di questo ritorno tutte le giustificazioni, le coordinate, oltre che morali, spaziali e temporali, anche per dare poi, per restituire og- gettivamente il quadro linguistico e temporale entro il quale mi muovo. 1 Space and time are important elements in all his novels, which are some- what fictional, but somewhat realistic, especially in the use of historical events and geographical descriptions, such as those of Ferrara, with its streets, monuments, bars, and inhabitants, including the Ferrarese Jew- ish community. As a writer of the generation following the Fascist era, Bassani was greatly concerned with establishing a strong tie to a con- crete reality 2 and finding a proper language that would «establish a link with reality in order to express authentic values and reveal historical truth» 3. -

Le Testimonianze Di Primo Levi E Di Giorgio Bassani Enzo Neppi

Sguardi incrociati sulla condizione ebraica in Italia nel XX secolo: le testimonianze di Primo Levi e di Giorgio Bassani Enzo Neppi To cite this version: Enzo Neppi. Sguardi incrociati sulla condizione ebraica in Italia nel XX secolo: le testimonianze di Primo Levi e di Giorgio Bassani. Sarah Amrani, Maria Pia De Paulis-Dalembert (dir.). Bassani nel suo secolo, Giorgio Pozzi editore, pp.325-346, 2017. hal-02898125 HAL Id: hal-02898125 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02898125 Submitted on 27 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. enzo nePPI Université Grenoble Alpes Sguardi incrociati sulla condizione ebraica in Italia nel XX secolo: le testimonianze di Primo Levi e di Giorgio Bassani Nati a distanza di soli tre anni in famiglie ebraiche colte 1 dell’Italia del Nord, Primo Levi e Giorgio Bassani hanno subito tutti e due le conseguenze della legislazione razziale a partire dal 1938 2 , e hanno entrambi meditato sulla condizione ebraica nel loro tempo, ma con sensibilità molto diverse, che si riflettono nelle loro opere 3 . La somiglianza delle situazioni che hanno affrontato dà un rilievo speciale alle loro diverse reazioni e rende il loro confronto particolarmente istruttivo. -

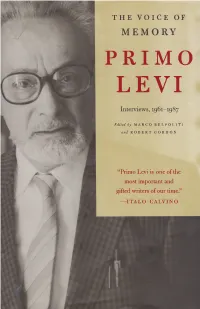

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Download (1541Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/77618 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Kate Elizabeth Willman PhD Thesis September 2015 NEW ITALIAN EPIC History, Journalism and the 21st Century ‘Novel’ Italian Studies School of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Warwick 1 ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………...... 4 Declaration …………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………….... 6 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………..... 7 - Wu Ming and the New Italian Epic …………………………………………………. 7 - Postmodern Impegno ……………………………………………………………….. 12 - History and Memory ……………………………………………………………….. 15 - Representing Reality in the Digital Age ………………………………………….... 20 - Structure and Organisation …………………………………………………………. 25 CHAPTER ONE ‘Nelle lettere italiane sta accadendo qualcosa’: The Memorandum on the New Italian Epic ……………………………………………………………………..... 32 - New ………………………………………………………………………………… 36 - Italian ……………………………………………………………………………….. 50 - Epic …………………………………………………………………………………. 60 CHAPTER TWO Periodisation ………………………………………………………….. 73 - 1993 ………………………………………………………………………………… 74 - 2001 ........................................................................................................................... -

Six Centuries of Italian Books from the Baillieu Library’S Special Collections Libri: Six Centuries of Italian Books from the Baillieu Library’S Special Collections

six centuries of Italian books from the Baillieu Library’s Special Collections Libri: six centuries of Italian books from the Baillieu Library’s Special Collections An exhibition held in the Leigh Scott Gallery, Baillieu Library University of Melbourne 17 June to 15 September 2013 curated by Susan Millard with assistance from Tom Hyde. Published 2013 by the Special Collections Level 3, Baillieu Library The University of Melbourne Victoria 3010 Australia 03 8344 5380 [email protected] www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/ special/ Copyright © the authors and the University of Melbourne 2013 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. All reasonable effort has been made to contact the copyright owners. If you are a copyright owner and have not been in correspondence with the university please contact us. Authors: Susan Millard and Tom Hyde Design: Janet Boschen Photography: Lee McRae ISBN 978 0 7340 4850 9 Cover: Owen Jones, The grammar of ornament, London: Day and son, 1856 (details). Leon Battista Alberti, Della Statua [Pittura] di Leon Battista Alberti, 1651 (details) Right: Marc Kopylov, Papiers dominotés italiens, 2012 Far right: Owen Jones, The grammar of ornament, 1856 FOREWORD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What could be better than an I would like to acknowledge the early input of Kylie King, who exhibition of Italian books to be threw some very interesting ideas included in Rare Book Week into the mix, but had to withdraw with the theme ‘A passion for from the project. A big thank you to books’? Our recent purchase of Tom Hyde, who has put time and the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, effort into the selection, installation an early printed book with and writing of text for the exhibition; it has been great working with exceptional woodcuts, printed him. -

David Ward Department of Italian Studies Wellesley College Wellesley, MA 02481 USA

David Ward Department of Italian Studies Wellesley College Wellesley, MA 02481 USA Office Phone: (781) 283 2617/Fax: (781) 283 2876 Email: [email protected] Education 1972-75, BA (Hons) in English and American Studies, awarded by the School of English and American Studies, University of East Anglia, Norwich, Great Britain 1984-88, MA and PhD in Italian Literature, awarded by the Department of Romance Studies, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Work Experience 1980-84, Lector, Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy 1988-89, Lecturer, Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 1989-95, Assistant Professor, Department of Italian, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA 1995-2002, Associate Professor, Department of Italian, Wellesley College 2002-present, Professor of Italian, Department of Italian Studies, Wellesley College Courses Taught at Wellesley College All levels of Italian language The Construction of Italy The Function of Narrative Narrative Practices (Comparative Literature Seminar) Fascism and Resistance Autobiography (Writing Seminar) Europe in the Aftermath of World War II Italy’s Other Half: The South in History and Culture Italy in the 1960s Italian Cinema The Cities of Italy Italian Mysteries Other Courses Introduction to Italian Medieval and Renaissance Culture Twentieth Century Italian Intellectual Thought David Ward/CV Publications 1984 "Translating Registers: Proletarian Language in 1984," in Quaderni di Filologia Germanica della Facoltà di Lettere e -

The Garden of Finzi-Continis, Compassion, and the Struggle to Affirm Identity

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, April 2018, Vol. 8, No. 4, 539-552 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.04.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Garden of Finzi-Continis, Compassion, and the Struggle to Affirm Identity Simonetta Milli Konewko University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, USA This work investigates De Sica’s depiction of compassion proposing new ways of examining the film. Remaining faithful to his neorealist responsibility to denounce the plight of others and the experience associated to World War Two, the director offers models of compassion associated with past circumstances and the subsequent recollection of them. In other instance, compassion becomes the result of imaginative and elaborated descriptions that contrast with the neorealist aesthetic. These creative depictions suggest compassion through technical elements. For instance, the usage of flashbacks, the long shots of the garden, the close-ups and tracking shots on specific components of the environment, the soft focus on certain characters are ways to reflect on past circumstances to outline a new awareness and perspective. Keywords: compassion, World War Two, The Holocaust, Italian film, neorealism, fascism Introduction The Garden of Finzi-Continis, winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1971, has been recognized as an international success of the early 1970s.1 It also received awards from the National Council of Churches, the Synagogue Council of America, the U.S. Catholic Conference, and the United Nations.2 The story opens in Ferrara and focuses on two Jewish families, the wealthy Finzi-Continis and the upper middle-class Bassanis, which are slowly being annihilated by the wave of anti-Semitism accompanying the Fascist movement after the racial laws were implemented. -

Volume 1, No. 1

Journal of Italian Translation Editor Luigi Bonaffini Associate Editors: Gaetano Cipolla Michael Palma Joseph Perricone Editorial Board Adria Bernardi Geoffrey Brock Franco Buffoni Peter Carravetta John Du Val Rina Ferrarelli Luigi Fontanella Irene Marchegiani Adeodato Piazza Nicolai Stephen Sartarelli Achille Serrao Cosma Siani Joseph Tusiani Lawrence Venuti Pasquale Verdicchio Journal of Italian Translation is an international journal devoted to the transla- tion of literary works from and into Italian-English-Italian dialects. All translations are published with the original text. It also publishes essays and reviews dealing with Italian translation. It is published twice a year: in April and in November. Submissions should be both printed and in electronic form and they will not be returned. Translations must be accompanied by the original texts, a brief profile of the translator, and a brief profile of the author. All submissions and inquiries should be addressed to Journal of Italian Translation, Department of Modern Lan- guages and Literatures, 2900 Bedford Ave. Brooklyn, NY 11210. [email protected] Book reviews should be sent to Joseph Perricone, Dept. of Modern Lan- guages and Literatures, Fordham University, Columbus Ave & 60th Street, New York, NY 10023. Subscription rates: U.S. and Canada. Individuals $25.00 a year, $40 for 2 years. Institutions: $30.00 a year. Single copies $12.00. For all mailing overseas, please add $8 per issue. Payments in U.S. dollars. Journal of Italian Translation is grateful to the Sonia Raizzis