Generic Instability and Identity in the Contemporary Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

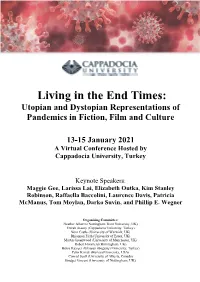

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

The Fever Dream of Documentary a Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(S): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol

The Fever Dream of Documentary A Conversation with Joshua Oppenheimer Author(s): Irene Lusztig Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Winter 2013), pp. 50-56 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/fq.2014.67.2.50 Accessed: 16-05-2017 19:55 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly This content downloaded from 143.117.16.36 on Tue, 16 May 2017 19:55:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE FEVER DREAM OF DOCUMENTARY: A CONVERSATION WITH JOSHUA OPPENHEIMER Irene Lusztig In the haunting final sequence of Joshua Oppenheimer’s with an elegiac blue light. The camera tracks as she passes early docufiction film, The Entire History of the Louisiana a mirage-like series of burning chairs engulfed in flames. Purchase (1997), his fictional protagonist Mary Anne Ward The scene has a kind of mysterious, poetic force: a woman walks alone at the edge of the ocean, holding her baby in wandering alone in the smoke, the unexplained (and un- a swaddled bundle. -

Download (1541Kb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/77618 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Kate Elizabeth Willman PhD Thesis September 2015 NEW ITALIAN EPIC History, Journalism and the 21st Century ‘Novel’ Italian Studies School of Modern Languages and Cultures University of Warwick 1 ~ TABLE OF CONTENTS ~ Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………...... 4 Declaration …………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………….... 6 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………..... 7 - Wu Ming and the New Italian Epic …………………………………………………. 7 - Postmodern Impegno ……………………………………………………………….. 12 - History and Memory ……………………………………………………………….. 15 - Representing Reality in the Digital Age ………………………………………….... 20 - Structure and Organisation …………………………………………………………. 25 CHAPTER ONE ‘Nelle lettere italiane sta accadendo qualcosa’: The Memorandum on the New Italian Epic ……………………………………………………………………..... 32 - New ………………………………………………………………………………… 36 - Italian ……………………………………………………………………………….. 50 - Epic …………………………………………………………………………………. 60 CHAPTER TWO Periodisation ………………………………………………………….. 73 - 1993 ………………………………………………………………………………… 74 - 2001 ........................................................................................................................... -

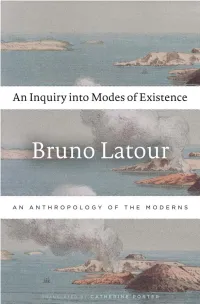

An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence

An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Anthropology of the Moderns · bruno latour · Translated by Catherine Porter Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence: Une anthropologie des Modernes, copyright © Éditions La Découverte, Paris, 2012. The research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (fp7/2007-2013) erc Grant ‘ideas’ 2010 n° 269567 Typesetting and layout: Donato Ricci This book was set in: Novel Mono Pro; Novel Sans Pro; Novel Pro (christoph dunst | büro dunst) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Latour, Bruno. [Enquête sur les modes d'existence. English] An inquiry into modes of existence : an anthropology of the moderns / Bruno Latour ; translated by Catherine Porter. pages cm “The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence : une anthropologie des Modernes.” isbn 978-0-674-72499-0 (alk. paper) 1. Civilization, Modern—Philosophy. 2. Philosophical anthropology. I. Title. cb358.l27813 2013 128—dc23 2012050894 “Si scires donum Dei.” ·Contents· • To the Reader: User’s Manual for the Ongoing Collective Inquiry . .xix Acknowledgments . xxiii Overview . xxv • ·Introduction· Trusting Institutions Again? . 1 A shocking question addressed to a climatologist (02) that obliges us to distinguish values from the ac- counts practitioners give of them (06). Between modernizing and ecologizing, we have to choose (08) by proposing a different system of coordinates (10). -

In Defense of Genre Blending

In Defense of Genre Blending. Author Affiliation Sarah E. Worth and Furman University, U.S. Sean McBratnie Abstract: Readers often only care about one distinction when it comes to things they read. Is it fiction or nonfiction? Did it happen or didn’t it? Presumably, we make sense of events we believe happened in a different way than we make sense of the ones that we don’t believe. Deconstructionists often warn us about the hazards that occur with the strict binary thinking we tend to orient ourselves with. When this binary is blurred, which it often is in many contemporary works of literature, readers become unsettled. It is our position that genre, and even the more broad categories of fiction and nonfiction, should not be found exclusively as properties internal to the text itself, but rather, the way we make sense of genre is an active process of narrative comprehension. We will question how the particular binary concerning fiction and nonfiction has sold us short concerning the ways in which we make sense of literary texts, and how much more fluid our notions of genre really could and should be. We also want to argue that the reduction of the binary of genre merely into fiction and nonfiction is a gross oversimplification of the ways in which we understand both genres themselves, as well as the ways in which we understand both truth and reference. Readers seem to care an awful lot about the apparent truth content of the books they choose. Is it fiction or non-fiction? Did it happen or did it not? Presumably, readers make sense of events they believe happened in a differ- ent way than they make sense of the ones that they don’t believe happened. -

Olmo and the Seagull

Nadica Denic Student nr: 10603557 [email protected] EMBODYING HYBRIDITY: Enactive-ecological approach to filmic self-perception and self- enactment in contemporary docufiction film Research Master Thesis Department of Media Studies University of Amsterdam Supervisor: Patricia Pisters Second reader: Abe Geil I express my gratitude to a number of people. I am thankful to Patricia Pisters for her guidance through my film-philosophical curiosities. To my family, for always being there. And to Adel, Mare and Matthias, who always made friendship a priority. Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Enactive-Ecological Theory of Perception ................................................................... 7 1.1 Embodied Cognition ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Ecological Affordances ....................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Cultural Modification of Affordances ................................................................................. 12 1.4 Mediation of Bodily Presence ............................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: Affordances of Filmic Self-Perception ....................................................................... 19 2.1 Mediating Spatiality ........................................................................................................... -

A Socio-Economic Study of the Camorra Through Journalism

A SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY OF THE CAMORRA THROUGH JOURNALISM, RELIGION AND FILM by ROBERT SHELTON BELLEW (under the direction of Thomas E. Peterson) ABSTRACT This dissertation is a socio-economic study of the Camorra as portrayed through Roberto Saviano‘s book Gomorra: Viaggio nell'impero economico e nel sogno di dominio della Camorra and Matteo Garrone‘s film, Gomorra. It is difficult to classify Saviano‘s book. Some scholars have labeled Gomorra a ―docufiction‖, suggesting that Saviano took poetic freedoms with his first-person triune accounts. He employs a prose and news reporting style to narrate the story of the Camorra exposing its territory and business connections. The crime organization is studied through Italian journalism, globalized economics, eschatology and neorealistic film. In addition to igniting a cultural debate, Saviano‘s book has fomented a scholarly consideration on the innovativeness of his narrative style. Wu Ming 1 and Alessandro Dal Lago epitomize the two opposing literary camps. Saviano was not yet a licensed reporter when he wrote the book. Unlike the tradition of news reporting in the United States, Italy does not have an established school for professional journalism instruction. In fact, the majority of Italy‘s leading journalists are writers or politicians by trade who have gravitated into the realm of news reporting. There is a heavy literary influence in Italian journalism that would be viewed as too biased for Anglo- American journalists. Yet, this style of writing has produced excellent material for a rich literary production that can be called engagé or political literature. A study of Gomorra will provide information about the impact of the book on current Italian journalism. -

IFFR Feature Film Contact List

Angola Air Conditioner World premiere Programme section: Bright Future Main Programme Director(s): Fradique Prod. Countries: Angola Prod. Year: 2020 Length: 72 Genre: Fiction 49th Company: Geração 80 INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Contact: Jorge Cohen ROTTERDAM Email: [email protected] Logline: Air conditioners mysteriously start January 22 – falling from buildings in the Angolan capital. February 02, 2020 The search for a working unit forms the starting point for an pleasantly free film representing the city's heartbeat. A great jazzy soundtrack, a rap FEATURE FILM CONTACT LIST and the chaotic hum of the city guide us through January 31, 2020 its streets and buildings. Sold territories: All available Argentina Los que vuelven International premiere Programme section: Voices Main Programme Director(s): Laura Casabé Prod. Countries: Argentina Prod. Year: 2019 Length: 93 Genre: Fiction Company: Reel Suspects Contact: Alejandro Israel Email: [email protected] Logline: In this drama dealing with fear and oppression in South America, supernatural powers are unleashed when, in desperation, the wife of a white landowner invokes the spirits of the indigenous people. Her stillborn child is Patagonia. The calm, unchanging nature of the brought back to life, but at a terrible price. Is this impressive landscape contrasts with her restless the feared retribution? inner life, and the people from her past elicit old Sold territories: Argentina emotions and new insights, some of which are not so uplifting. Las poetas visitan a Juana Bignozzi Trailer: International premiere https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hgAm8iev Programme section: Signatures Szw Director(s): Laura Citarella, Mercedes Halfon Sold territories: All available Prod. -

Film 185S Advanced Topics in Film Studies: Docu-Fiction

FILM 185S: Docu-Fiction UCSC Summer 18 A. Delgado Pereira Film 185S Advanced Topics in Film Studies: Docu-Fiction Summer 2018 (Session I) Tuesday + Thursday 01:00PM – 04:30PM Earth & Marine B210 Instructor: Arturo Delgado Pereira Dept. of Film and Digital Media [email protected] Office hours: Wednesday 2:30PM- 4:30PM (or By appointment) at McHenry LiBrary LoBBy. DESCRIPTION OF THE COURSE This course will explore documentary film approaches that call into question the traditional categories of “fiction” and “documentary”: hybrid films, documentary re-enactments, improvisational fictions, narrative provocations, performative documentaries, etc. Students will be able to identify the origins of film works that mix documentary and fictional film approaches, and some of their most remarkable examples, as well as evaluate how these techniques advance and/or hinder the documentary project. Students will be required to develop a short film proposal that uses "docufictional” approaches. Classes will be composed of lectures, critical viewing and discussion of screenings. LEARNING OUTCOMES After completing this course, you will be able to: Ø Explain the origins of film works that mix documentary and fictional film techniques. Ø Identify some of the most remarkable approaches used in so-called docu-fiction films. Ø Evaluate and describe how these techniques advance and/or hinder the documentary project. Ø Demonstrate knowledge of contemporary trends in form and content by creating meaningful, innovative and contemporary film projects ideas. REQUIRED MATERIAL Ø Articles and other assigned materials will be uploaded to the Canvas site of the course. https://its.ucsc.edu/canvas/canvas-student.html Ø Film material: Most required films are either held at the McHenry Library Digital Scholarship Commons (aka the “Media Center”) or can be streamed via Kanopy (the UCSC library streaming service): https://www.kanopy.com. -

Bronwen Pugsley

CHALLENGING PERSPECTIVES: DOCUMENTARY PRACTICES IN FILMS BY WOMEN FROM FRANCOPHONE AFRICA Bronwen Pugsley Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Nottingham, 2011 ABSTRACT This thesis is located at the intersection of three dynamic fields: African screen media, documentary studies, and women’s filmmaking. It analyses a corpus of fifteen films by Francophone sub-Saharan African women filmmakers, ranging from 1975 to 2009, within the framework of documentary theory. This study departs from the contextual approach to African women’s documentary, which has been predominant among scholarship and criticism thus far, in favour of a focus on the films as texts. The popular models developed for the study of documentary film by Western scholars are applied to African women’s documentaries in order to explore their innovative and stimulating practices; to determine the degree to which such models are fully adequate or, instead, are challenged, subverted, or exceeded by this new context of application; and to address the films’ wider implications regarding the documentary medium. Chapter One outlines the theoretical framework underpinning the thesis and engages with existing methodologies and conventions in documentary theory. Chapter Two considers women-centred committed documentary, analyses the ways in which these films uncover overlooked spaces and individuals, provide and promote new spaces for the enunciation of women’s subjectivity and ‘herstories’, and counter hegemonic stereotypical perceptions of African women. Chapter Three addresses recent works of autobiography, considers the filmmaking impulses and practices involved in filming the self, and points to the emergence of a filmmaking form situated on the boundary between ethnography and autobiography. -

Video Research: Documenting and Learning from Hiv and Aids Communication Strategies for Social Change in Ghana

VIDEO RESEARCH: DOCUMENTING AND LEARNING FROM HIV AND AIDS COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES FOR SOCIAL CHANGE IN GHANA by Heiko Decosas BA Communications, SFU 2006 PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF COMMUNICATION In the School of Communication © Heiko Decosas 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Declaration of Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the “Institutional Repository” link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Fictioning the Landscape

Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology ISSN: 2053-9320 (Print) 2053-9339 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfap20 Fictioning the Landscape Simon O’Sullivan To cite this article: Simon O’Sullivan (2018) Fictioning the Landscape, Journal of Aesthetics and Phenomenology, 5:1, 53-65, DOI: 10.1080/20539320.2018.1460114 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20539320.2018.1460114 Published online: 31 May 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfap20 JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS AND PHENOMENOLOGY, 2018 VOL. 5, NO. 1, 53–65 https://doi.org/10.1080/20539320.2018.1460114 Fictioning the Landscape Simon O’Sullivan Visual Cultures, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper develops a concept of fictioning when this names, in Film-essay; docufiction; part, the deliberate imbrication of an apparent reality with other fictioning; landscape narratives. It focuses on a particular audio-visual example of this kind of art practice, known as the film-essay or what Stewart Home has called called the “docufiction.” The latter operates on a porous border between fact and fiction, but also between fiction and theory and, at times, the personal and political. In particular the paper is concerned with how the docufiction can involve a presentation of landscape, broadly construed, alongside the instantiation of a complex and layered temporality which itself involves the foregrounding of other pasts and possible futures. “Fictioning the landscape” also refers to the way in which these different space-times need to be performed in some way, for example with a journey through or to some other place as in a pilgrimage.