Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY LIBRARY. Special Collections

EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY LIBRARY. Special Collections Handlist of Manuscripts, H 29 JOHN WAIN ARCHIVE MSS 2851-2875; MSS 3124-3137 E97.67 Literary manuscripts of John Barrington Wain (1925-1994) were deposited in Edinburgh University Library in 1974, and subsequently added to by the author until 1986, when the whole deposit was purchased by the Library with the help of the Local Museums Purchase Fund. These manuscripts constitute MSS 2851-2874. Some items were deposited after 1985 and these, along with the manuscripts in the possession of the author at his death were purchased in 1996, with the aid of the National Fund for Acquisitions. These manuscripts constitute MSS 3124-3137. Further manuscripts were found by his family subsequently and were gifted in December 1997: these manuscripts constitute E97.67. This group is not sorted or listed and needs to integrated with MSS 3124-3137 as the material is closely linked with the material in this group, e.g. further mss and tss of his Oxford trilogy. Wain’s incoming correspondence and outgoing letters to Philip Larkin were purchased with the help of the National Fund for Acquisitions in 1999 (E99.01). These are included in MS 2875. The manuscript of his first novel, Hurry on Down (1953), has not survived, but notebooks, mss and typescripts of most of his later novels, short stories, poetry, plays and criticism are present. The list below was compiled at different times, and conventions regarding italicization, etc. are not consistent. (Note: See the 1985 Edinburgh University Library exhibition catalogue 'Hurry Back Down: John Wain at Sixty' for further information. -

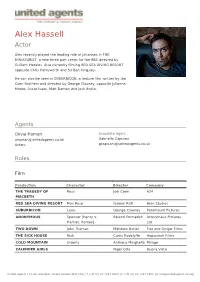

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

The Oxford Anthology of English Poetry: Volume 2: Blake to Heaney Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE OXFORD ANTHOLOGY OF ENGLISH POETRY: VOLUME 2: BLAKE TO HEANEY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Wain | 800 pages | 15 May 2003 | Oxford University Press | 9780192804228 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The Oxford Anthology of English Poetry: Volume 2: Blake to Heaney PDF Book Brand new Book. Return to Book Page. Encompassing a broad range of subjects, styles, and moods, English poetry of the late eighteenth We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Nick H rated it it was amazing Oct 12, Quantity Add to basket. The richness and variety of this tradition are represented in this collection by all the great and familiar names, but also some of the less well-known poets who have often provided startling exceptions to the poetry of their age. Ten Poems About Cats. Anthony Holden. Various Poets. How Han rated it it was ok Jul 08, Sign in to Purchase Instantly. John Wain. Carolyne Larrington. Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. Stephen Conlon. Ten Poems About London. Preferred contact method Email Text message. Reset password. The result is a rich and multi-coloured tapestry of the depth, diversity, and energy of poetry written in Britain and Ireland. Academic Skip to main content. Other Editions 1. Laura rated it liked it Jun 14, About John Wain. Call us on or send us an email at. Bobby rated it really liked it Feb 26, We are republishing these classic works in affordable, high quality, modern editions, using the original text and artwork. -

John Wain.Pdf

JOHN W AIN: EL REI'ORNO DE LA TRADICION PICARESCA A LA NOVELA INGLESA En la década de los cincuenta un nombre nuevo aparece en el panorama literario inglés: John Wain. Siendo profesor de literatura inglesa en la Universidad de Reading, a la edad de 28 años, publica su primera novela, Hurry On Down, (1953), que inmediatamente atrae la atención de gran parte de la crítica del momento. Por su protagonista rebelde y crítico del sistema, algunos enmarcan esta obra y a su autor entre los denominados "Angry young Men", 1 grupo de jóvenes escritores que protestan airadamente contra los defectos de su sociedad y cuyo principal representante es el dramaturgo John Osborne con su obra Look Rack in Anger (1956). Otros críticos, sin embargo, asocian aJobo Wain con un grupo de novelistas y poetas anterior conocido como "The Movement",2 y que reúne a nombres tan notables como los de Kingsley Amis, Philip Larkin, Donald Davie, Elizabeth Jennings o ThomGunn. Al margen de la conveniencia o no de adscribir la figura de John Wain a un movimiento literario concreto, 10 cierto es que es uno de los pioneros de las nuevas tendencias que surgen en la literatura inglesa de los años cincuenta. Hurry On Down es una de las primeras novelas de la posguerra que vuelve hacia los cánones realistas tradicionales, después de casi medio siglo de experimentación modernista. Y 10 que es más significativo, con su publicación en octubre de 1953 tiene lugar el retorno de la tradición picaresca a la literatura inglesa. Este camino, que en parte había sido ya iniciado por la obra de William Cooper, Scenes From Provincial Life (1950), 1,_ Cf. -

N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd”

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd” Neema Parvini (Royal Holloway, University of London) In 1958, in the Observer , Kenneth Tynan wrote of “a dazzling new playwright,” with his inimitable enthusiasm he declared: “I am ready to burn my boats and promise [that] N.F. Simpson [is] the most gifted comic writer the English stage has discovered since the war” (Tynan 210). Now, in 2008, despite a recent West End revival, 1 few critics would cite Simpson at all and debates regarding the “most gifted comic writer” of the English stage would invariably be centred on Tom Stoppard, Joe Orton, Samuel Beckett or, for those with a more morose sense of humour, Harold Pinter. Part of the reason for Simpson’s critical decline can be put down to protracted periods of silence; after his run of critically and commercially successful plays with The English Stage Company, 2 Simpson only produced two further full length plays: The Cresta Run (1965) and Was He Anyone? (1972). Of these, the former was poorly received and the latter only reached the fringe theatre. 3 As Stephen Pile recently put it, “in 1983, Simpson himself vanished” with no apparent fixed address. The other reason that may be cited is that, more than any other British writer of his time, Simpson was associated with “The Theatre of the Absurd.” As the vogue for the style died out in London, Simpson’s brand of Absurdism simply went out of fashion. John Russell Taylor offers perhaps the most scathing version of that argument: “whether one likes or dislikes N.F. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Harold Pinter: the Dramatist and His World

Harold Pinter: The Dramatist and His World Background Nobel winner, Harold Pinter (1930- 2008) was born in London, England in a Jewish family. Some of the most recognizable features in his plays are the use of understatement, small talk, distance, and silence. These devices are employed to convey the substance of a character’s thoughts. At the outbreak of World War II, Pinter was evacuated from the city to Cornwall; to be wrenched from his parents was a traumatic event for Pinter. He lived with 26 other boys in a castle on the coast. At the age of 14, he returned to London. "The condition of being bombed has never left me," Pinter later said. At school one of Pinter's main intellectual interests was English literature, particularly poetry. He also read works of Franz Kafka and Ernest Hemingway, and started writing poetry for little magazines in his teens. The seeds of rebellion in Pinter could be spotted early on when he refused to do the National Service. As a young man, he studied acting at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the Central School of Speech and Drama, but soon left to undertake an acting career under the stage name David Baron. He travelled around Ireland in a Shakespearean company and spent years working in provincial repertory before deciding to turn his attention to playwriting. Pinter was married from 1956 to the actress Vivien Merchant. For a time, they lived in Notting Hill Gate in a slum. Eventually Pinter managed to borrow some money and move away. Although Pinter said in an interview in 1966, that he never has written any part for any actor, his wife Vivien frequently appeared in his plays. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Desmond Pacey, ed. The Letters of Frederick Philip Grove, Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1976. pp. 584. $25.00. On January 15, 1941, a 23-year-old professor of English at Brandon College wrote to Frederick Philip Grove in Simcoe, Ontario, requesting information needed for a radio talk on the former Manitoba novelist. Just out from Cambridge, the young scholar had been asked to participate in "The University of the Air" series, to which the University of Manitoba was contributing a number of "Manitoba Sketches." "I was asked to cover the field of Manitoba literature," the professor recalls, "[and] as the only Manitoba literature I had then read was Grove's novels, I made [his] novels the SUbject of my talk." It is likely that Grove did not hear this talk, broadcast over local Manitoba stations, but this exchange of letters marked the beginning of Desmond Pacey's formal study of Grove, which culminated in his book-length study of the novelist in 1945. In the thirty-five years that have elapsed since that first letter, Pacey has been singularly dedicated to keeping Grove's name before the public, and though he has been upstaged recently by the sleuthing of Douglas Spettigue in regards to Grove's life, his body of critical assessments about his fiction still stands as a requisite for the Grove scholar. It is therefore fitting that Pacey should have capped his career with this monumental collection of Grove's letters, completed just before his untimely death on July 4, 1975, which to my knowledge is, aside from the Selected Letters of Malcolm Lowry, the only collection of letters ever published on a major Canadian literary figure. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

Reflection of Psychic Distemper in the Selected Plays of Osborne

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Reflection of Psychic Distemper in the Selected plays of Osborne Twishampati Research Scholar in Ranchi University. Abstract: John Osborne was well- known among the members of this ‘Angry’ tradition. Again, Critics blamed the all- too frequent use of the phrase “Angry Young Men”, one which was “employed to a group without so much as an attempt at understanding all those complacency, the idealistic bankruptcy of their environment”(Maschler,Declaration,P.7). Some other important members of the so- called “Angries” were novelists Kingsley Amis and John Wain. Osborne was the most significant figure of this ‘Angry’ movement, if not the outright innovator of the trend. Hayman mentioned “Beckett, Osborne, Pinter and Arden as the four most important talents to emerge in the theatre in the mid- nineteen fifties. Of the four, he ensured, Osborne had the most direct influence on the new movement, in that he did more than anyone to popularise the new type of the hero and the new type of actor” (Hayman, Evening News, quoted in Casebook Series, P.46). Though Osborne only discontentedly allowed to it, one could consider that his play Look Back in Anger first produced in 1956 initiated the “Angry “movement. Again, it is regarded that ‘Angry Young Men’ is new generation of writers appeared on the scene in 1950s Britain. The 1950s decade is remembered as the angry decade. The most famous of them were novelists like John Braine, John Wain and Kingsley Amis and the playwright John Osborne. All of them were the followers of Labour Government. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I witnessed the demonstrations against Terrence McNally’s play, Corpus Christi, in 1999 at Edinburgh’s Bedlam Theatre, the home of the University’s student theatre company. But these protests were not taken seriously by any- one I knew: acknowledged as a nuisance, certainly, but also judged to be very good for publicity in the competitive Festival fringe. 2. At ‘How Was it for You? British Theatre Under Blair’, a conference held in London on 9 December 2007, the presentations of directors Nicholas Hytner, Emma Rice and Katie Mitchell, writers Mark Lawson, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Tanika Gupta and Mark Ravenhill, and actor and Equity Rep Malcolm Sinclair all included reflection upon issues of censorship, the policing of per- formance or indirect forms of constraint upon content. Ex-Culture Minister Tessa Jowell’s opening presentation also discussed censorship and the closure of Behzti. 3. Andrew Anthony, ‘Amsterdammed’, The Observer, 5 December 2004; Alastair Smart, ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread’, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 December 2006. 4. Christian Voice went on to organise protests at the theatre pro- duction’s West End venue and then throughout the country on a national tour. ‘Springer protests pour in to BBC’, BBC News, 6 January 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/tv_and_radio/4152433.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]. 5. Angelique Chrisafis, ‘Loyalist Paramilitaries Drive Playwright from His Home’, The Guardian, 21 December 2005. 6. ‘Tate “Misunderstood” Banned Work’, BBC News, 26 September 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/entertainment/arts/4281958.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]; for discussion of the Bristol Old Vic’s decision, see Ian Shuttleworth, ‘Prompt Corner’, Theatre Record, 25.23, 6 December 2005, pp. -

In Spite of History? New Leftism in Britain 1956 - 1979

In Spite of History? New Leftism in Britain 1956 - 1979 Thomas Marriott Dowling Thesis Presented for the Degree of PhD Department of History University of Sheffield August 2015 ii iii Contents Title page p. i Contents p. iii Abstract p. vi Introduction p. 1 On the Trail of the New Left p. 5 Rethinking New Leftism p. 12 Methodology and Structure p. 18 Chapter One Left Over? The Lost World of British New Leftism p. 24 ‘A Mood rather than a Movement’ p. 30 A Permanent Aspiration p. 33 The Antinomies of British New Leftism p. 36 Between Aspiration and Actuality p. 39 The Aetiology of British New Leftism p. 41 Being Communist p. 44 Reasoning Rebellion p. 51 Universities and Left Review p. 55 Forging a Movement p. 58 CND p. 63 Conclusion p. 67 iv Chapter Two Sound and Fury? New Leftism and the British ‘Cultural Revolt’ of the 1950s p. 69 British New Leftism’s ‘Moment of Culture’? p. 76 Principles behind New Leftism’s Cultural Turn p. 78 A British Cultural Revolt? p. 87 A New Left Culture? p. 91 Signifying Nothing? p. 96 Conclusion p. 99 Chapter Three Laureate of New Leftism? Dennis Potter’s ‘Sense of Vocation’ p. 102 A New Left ‘Mood’ p. 108 The Glittering Coffin p. 113 A New Left Politician p. 116 The Uses of Television p. 119 History and Sovereignty p. 127 Common Culture and ‘Occupying Powers’ p. 129 Conclusion p. 133 Chapter Four Imagined Revolutionaries? The Politics and Postures of 1968 p. 135 A Break in the New Left? p.