From Pleasure to Menace: Noel Coward, Harold Pinter, and Critical Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gregory Clarke Sound Designer

Gregory Clarke Sound Designer Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF SHADES Almeida By Beth Steel 2020 Dir. Blanche McIntyre ALL OF US National Theatre By Francesca Martinez 2020 Dir. Ian Rickson THE REALISTIC JONESES Theatre Royal Bath By Will Eno 2020 Dir. Simon Evans Theatre Production Company Notes THE BOY FRIEND Menier Chocolate Factory Book, Music and Lyrics by Sandy Wilson 2020 Dir. Matthew White THE WIZARD OF OZ Chichester Festival Adapted by John Kane from the motion 2019 Theatre picture screenplay A DOLL'S HOUSE Lyric Hammersmith By Henrik Ibsen in a new adaptation by 2019 Tanika Gupta Dir. Rachel O’Riordan. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE SECRET DIARY OF Ambassadors Theatre Based on the novel by Sue Townsend ADRIAN MOLE AGED 13 3/4 Dir. Luke Sheppard Book & Lyrics by 2019 Jake Brunger, Music & Lyrics by Pippa Cleary Transfer of Menier Chocolate Factory production THE BRIDGES OF MADISON Menier Chocolate Factory Book by Marsha Norman COUNTY Music & Lyrics by Jason Robert Brown 2019 Based on the novel by Robert James Waller Direction Trevor Nunn THE BEACON Druid By Nancy Harris 2019 Dir. Garry Hynes RICHARD III Druid / Lincoln Center NYC By William Shakespeare 2019 Dir. Garry Hynes ORPHEUS DESCENDING Theatr Clwyd / Menier By Tennessee Williams 2019 Chocolate Factory Dir. Tamara Harvey THE BAY AT NICE Menier Chocolate Factory By David Hare 2019 Dir. -

The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama in John Osborne's

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (September. 2018) 77-80 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama In John Osborne’s “ Look Back In Anger” Sadaf Zaman Lecturer University of Bisha Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Sadaf Zaman ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission:16-09-2018 Date of acceptance: 01-10-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- John Osborne was born in London, England in 1929 to Thomas Osborne, an advertisement writer, and Nellie Beatrice, a working class barmaid. His father died in 1941. Osborne used the proceeds from a life insurance settlement to send himself to Belmont College, a private boarding school. Osborne was expelled after only a few years for attacking the headmaster. He received a certificate of completion for his upper school work, but never attended a college or university. After returning home, Osborne worked several odd jobs before he found a niche in the theater. He began working with Anthony Creighton's provincial touring company where he was a stage hand, actor, and writer. Osborne co-wrote two plays -- The Devil Inside Him and Personal Enemy -- before writing and submittingLook Back in Anger for production. The play, written in a short period of only a few weeks, was summarily rejected by the agents and production companies to whom Osborne first submitted the play. It was eventually picked up by George Devine for production with his failing Royal Court Theater. Both Osborne and the Royal Court Theater were struggling to survive financially and both saw the production of Look Back in Anger as a risk. -

Psychological Insight in Look Back in Anger Dr

© 2020 IJRAR February 2020, Volume 7, Issue 1 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Psychological insight in Look Back in Anger Dr. Swati Tande Assist. Professor, Department of English, P.N. College, Nanded Abstract: This research paper intends to study Look Back in Anger as a problem play. The paper deals with the aspects of social conflicts consequent upon individual conflicts. Sense of loss in modern generation is the key concept of the play. The sense of loss leads to depression in modern people is reflected through the paper. The plot of Look Back in Anger moves from love, jealousy, misunderstanding, hatred, and reconciliation. Osborne had dramatized communal questions in order to arouse social conscience. The play presents the frustrated outbursts of Jimmy, the angry young man. He frenzied with resentment against conservative class system. Instead of facing the problems, the protagonist just grumbles for the people and situation in which he his living. Dealing with psyche of modern world, Osborne presented degeneration of generation. Key Words: psychological, rationale, reciprocal, obligation, alienation, reconciliation, compatibility. John Osborne was a born playwright. In his creative world dramatic expression comes with a perfect naturalness and ease. He remained defiantly a popular dramatist who was capable of speaking to a mass public. His play has a sense of social complexity. His major plays, particularly problem plays have never ceased to be the ‘lessons in feeling’. The depiction of the middle age group by Osborne is true to fact. Through his plays, Osborne had opened up a much wider subject than rebelliousness or youthful anger, that of social alienation. -

Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances

Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances Abstract Famous athletes are increasingly cultivating signature dances and celebratory moves, such as touchdown dances, as valuable and commercially viable elements of their personal brands. As these personal branding devices have become immediately recognizable and have begun being commercially exploited, athletes need to legally protect their signature dances. This paper argues that trademark law should protect the signature dances and moves of famous athletes, particularly the signature touchdown dances of NFL players. Because touchdown dances are devices capable of distinguishing one player from another, are non- functional, and are commercially used in NFL games, the dances should be registrable with the USPTO as trademarks for football services. Trademark Rights for Signature Touchdown Dances Joshua A. Crawford Table of Contents I. Introduction . 1 A. Aaron Rodgers and the “Discount Double Check” . 1 B. Signature Dances and Moves in Sports . 4 C. Trademark Protection for Signature Sports Dances . 8 II. Trademark Eligibility and Registration for Signature Touchdown Dances . 10 A. Background Principles of American Trademark Law . 11 B. Subject-Matter Eligibility. 12 C. Distinctiveness . 15 1. Distinctiveness Background . .. 15 2. Acquired Distinctiveness for Dances with Secondary Meaning . 18 3. The Possibility of Proving Inherent Distinctiveness under Seabrook . 19 4. The Possibility of Wal-Mart Barring Inherent Distinctiveness . 20 D. Functionality . 21 E. Use in Commerce . 24 1. Interstate Commerce . 24 2. Bona Fide Commercial Use . 25 a. Manner of Use . 26 b. Publicity of Use . 28 c. Frequency of Use . 31 III. Infringement . 33 A. Real-World Unauthorized Copying of Dances among Players—Permissible Parody . 34 B. -

Interpretation of the Subtext of Harold Pinter's the Room, a Thematic Study

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 3, Issue 3, March 2015, PP 51-58 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Interpretation of the Subtext of Harold Pinter’s the Room, A Thematic Study Mona F. Hashish Northern Border University, Saudi Arabia [email protected] Keywords: Harold Pinter, subtext, silence, fear and violence. Harold Pinter (1930- 2008) is a modern British Noble-prize winning dramatist. The research tackles his first play The Room (1957). That play represents Pinter’s early subtle plays where he hides meanings within their folds. In his early phase, Pinter chooses to be silent, discreet and indirect in both language and characterization. The research studies the unspoken in The Room because it tells important and crucial information about the characters, their thoughts and their past. Pinter makes his play so ambiguous that it is not understood without analyzing what is said and what is not said. Moreover, the study treats the main themes in the play: alienation, violence, menace and fear. Therefore, the research investigates the subtext in order to reveal the embedded meanings of the text. The Room primarily discusses Rose’s tragedy that is unsaid. The protagonist’s reaction reflects her suffering. The paper manages to discover the reasons of her tragedy through studying her attitude, and analyzing her actions, reactions, silence and gestures. The Room is one of Harold Pinter‘s early plays that are vague and highly suggestive. John Brown calls Pinter‘s early plays –such as The Room (1957), The Birthday Party (1958), The Dumb Waiter (1959), The Caretaker (1960) and The Homecoming (1965) –‗interior plays‘ because they are all subtle and implicit (12). -

Players Conjures up Blithe Spirit

Inside this Issue Hairspray Auditions ..........................2 Mystery Photo ..................................2 Lab Show Preview ............................3 Historian’s Corner .............................3 Lab Show Rehearsal Pictures ............4 Vol. 7.6 March, 2012 Players Conjures Up Blithe Spirit by Bob McLaughlin Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit is possibly the best and Coward wrote this certainly the funniest example of its genre: the drama very funny comedy of paranormal bigamy. It tells the story of writer Charles in the midst of tragic Condomine, who, in order to research the supernatural, circumstances. invites his friends Dr. and Mrs. Bradman along with a His apartment and local medium, Madame Arcati, to a dinner-party-cum- office having been séance. The proceedings appear to be a bust until, after destroyed in the the guests have left, Charles is confronted with the ghost German bombing of his late wife, Elvira. He is also confronted with the of London, he problem of how to explain this to his second and very took a holiday in much alive wife, Ruth. The play goes on to explore Portmeirion, Wales such questions as: Does love survive past the grave? (the eccentric town Do wedding vows lapse after the funeral? Can one be where the classic TV jealous of ectoplasm? Can Madame Arcati un-conjure series The Prisoner spirits? How will the maid clean up after all this? was filmed), and was inspired to write an escapist play that might entertain his countrymen in wartime. He claimed to have written the script in five days and to have changed barely a line before its premiere in London on July 21, 1941. -

Theatre of the Absurd : Its Themes and Form

THE THEATRE OF THE ABSURD: ITS THEMES AND FORM by LETITIA SKINNER DACE A. B., Sweet Briar College, 1963 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Speech KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1967 Approved by: c40teA***u7fQU(( rfi" Major Professor il PREFACE Contemporary dramatic literature is often discussed with the aid of descriptive terms ending in "ism." Anthologies frequently arrange plays under such categories as expressionism, surrealism, realism, and naturalism. Critics use these designations to praise and to condemn, to denote style and to suggest content, to describe a consistent tone in an author's entire ouvre and to dissect diverse tendencies within a single play. Such labels should never be pasted to a play or cemented even to a single scene, since they may thus stifle the creative imagi- nation of the director, actor, or designer, discourage thorough analysis by the thoughtful viewer or reader, and distort the complex impact of the work by suppressing whatever subtleties may seem in conflict with the label. At their worst, these terms confine further investigation of a work of art, or even tempt the critic into a ludicrous attempt to squeeze and squash a rounded play into a square pigeon-hole. But, at their best, such terms help to elucidate theme and illuminate style. Recently the theatre public's attention has been called to a group of avant - garde plays whose philosophical propensities and dramatic conventions have been subsumed under the title "theatre of the absurd." This label describes the profoundly pessimistic world view of play- wrights whose work is frequently hilarious theatre, but who appear to despair at the futility and irrationality of life and the inevitability of death. -

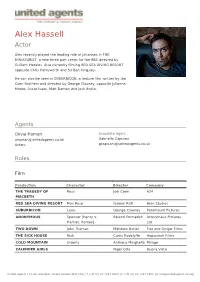

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

Hay Fever by Noel Coward

Central Washington University Theatre Arts Department presents Hay Fever By Noel Coward Prepared by Maureen Eller, assistant director and dramaturg 1 Central Washington University Theatre Arts Department Hay Fever Study Guide v Synopsis of Hay Fever v Noël Coward, playwright v The Taylor Family § Laurette Taylor v The Period § Timeline of Events v Glossary of Terms v Comments on Hay Fever v Sources Student matinee Nov. 22 at 11 a.m. TOWER THEATRE Produced by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. Synopsis A luminous and entertaining comedy, Hay Fever introduces you to the Bliss family: a retired actress mother, a novelist father, and two children for whom all the world, literally, is a stage. Their outrageous antics alternately infuriate and astound their hapless weekend guests, all of whom have been individually invited up for a weekend tete-a-tete. Rousing fights, surprise engagements, and fevered declarations of love drive the poor guests from the house, leaving the 2 family happily bickering and playing amongst themselves as this stylish comedy bounces to its inevitable and intoxicating end. Noel Coward Life of Noël Coward: Actor, Composer, Playwright, Director, Author, Celebrity *(Classic Magazine) 1899 Born in Teddington, Middlesex 16th December. 1907 First public stage appearances. 1922 Spends winter in New York on a subsistence income, and becomes frequent guest at the home of Laurette Taylor and Hartley Manners. 1923 Composes London Calling; writes The Vortex (produced 1924); writes Fallen Angels (produced 1925); Weatherwise (produced 1932). 1924 Appears in The Vortex; writes Hay Fever; produced Easy Virtue. 1925 Directs Hay Fever at the Ambassadors and Criterion Theatres. -

Home Chat 29/07/2010 12:13 Page 1

Aug2010_Home Chat 29/07/2010 12:13 Page 1 THE NEWSLETTER OF THE NOËL COWARD SOCIETY President: HRH The Duke of Kent Vice Presidents: Barry Day OBE • Stephen Fry • Tammy Grimes • Penelope Keith CBE AUGUST 2010 t was with surprise and sadness that the NCS committee Barbara Longford greeted Barbara Longford’s announcement that she wished Ito stand down as its chairman. For all of us Barbara’s name has become synonymous with Brief Encounter the Society and with the enormous programme of activity and events that has marked her hugely successful period as Design For Living Chairman. She has decided to move on to pursue her desire to support the work of the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Coward Celebrations Families Association (SSAFA). We wish her well with her new role and commitments and celebrate her contribution to the work of the Society in our centre pages recalling the highlights of her time with us. Warmest thanks from all of us for all the fun, the style and the passion of her contribution to our hero - to: ‘The Mistress’ from all of the lovers of ‘The Master.’ BRIEF ENCOUNTER RETURNS TO BROADWAY A NOËL COWARD SOCIETY EVENING he Roundabout Theatre Company in association with David Pugh & Dafydd Rogers and Cineworld presents T Kneehigh Theatre’s production of Noël Coward’s Brief Encounter adapted by Emma Rice. The production opens at Studio 54 in New York for previews on September 10, 2010. Stephen Greenman and Barbara Longford at Sardi’s in December Following opening on September 28th there will be a limited 2005. -

The Theme of Isolation in Harold Pinter's the Caretaker

www.the-criterion.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English ISSN (0976-8165) The Theme of Isolation in Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker Dr. H.B. Patil The human being in modern life has become victim of frustration, loneliness, loss of communication and isolation. Harold Pinter, the British playwright reflects exactly this state of human being in his play The Caretaker. His well known plays are The Room, The Homecoming , The Birthday Party, etc. But his real breakthrough came with the publication of The Caretaker. Harold Pinter’s works present directly or indirectly the influences of pre-war and post-war incidents. The sense of rootlessness, loneliness and isolation can be seen in his characters. The audiences are made to laugh but at the same time they are threatened by violent action that destroys the central character. The Caretaker discusses the critical condition of characters in the play. All the three characters Aston, Mick and Davies do represent their isolation with more or less intensity. This play of Pinter opens the life in general and life in 1950s England in particular. The isolation is either forced on them or it is selected by them on their own. His characters do not allow themselves to form good relationship with others. From the very beginning of the play, the realistic details occur. Aston lives in a room of an apartment that is owned by his brother Mick. Though they are brothers there is no proper communication between them. Aston lives the life of mentally retarded human being because of the electric shock treatment given to him. -

Hamlet West End Announcement

FOLLOWING A CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED & SELL-OUT RUN AT THE ALMEIDA THEATRE HAMLET STARRING THE BAFTA & OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING ANDREW SCOTT AND DIRECTED BY THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR ROBERT ICKE WILL TRANSFER TO THE HAROLD PINTER THEATRE FOR A STRICTLY LIMITED SEASON FROM 9 JUNE – 2 SEPTEMBER 2017 ‘ANDREW SCOTT DELIVERS A CAREER-DEFINING PERFORMANCE… HE MAKES THE MOST FAMOUS SPEECHES FEEL FRESH AND UNPREDICTABLE’ EVENING STANDARD ‘IT IS LIVEWIRE, EDGE-OF-THE-SEAT STUFF’ TIME OUT Olivier Award-winning director, Robert Icke’s (Mary Stuart, The Red Barn, Uncle Vanya, Oresteia, Mr Burns and 1984), ground-breaking and electrifying production of William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, starring BAFTA award-winner Andrew Scott (Moriarty in BBC’s Sherlock, Denial, Spectre, Design For Living and Cock) in the title role, will transfer to the Harold Pinter Theatre, following a critically acclaimed and sell out run at the Almeida Theatre. Hamlet will run for a limited season only from 9 June to 2 September 2017 with press night on Thursday 15 June. Hamlet is produced by Ambassador Theatre Group (Sunday In The Park With George, Buried Child, Oresteia), Sonia Friedman Productions and the Almeida Theatre (Chimerica, Ghosts, King Charles III, 1984, Oresteia), who are renowned for introducing groundbreaking, critically acclaimed transfers to the West End. Rupert Goold, Artistic Director, Almeida Theatre said "We’re delighted that with this transfer more people will be able to experience our production of Hamlet. Robert, Andrew, and the entire Hamlet company have created an unforgettable Shakespeare which we’re looking forward to sharing even more widely over the summer in partnership with Sonia Friedman Productions and ATG.” Robert Icke, Director (and Almeida Theatre Associate Director) said “It has been such a thrill to work with Andrew and the extraordinary company of Hamlet on this play so far, and I'm delighted we're going to continue our work on this play in the West End this summer.