A Foucaldian Reading of Harold Pinter's Old Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Certain Plays by Harold Pinter

COMEDY IN THE SEVENTIES: A STUDY OF CERTAIN PLAYS BY HAROLD PINTER Annette Louise Combrink A thesis submitted to the Facul ty of Arts, Potchefstroom University for Christian High er Education in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor Litterarum Promoter: Prof. J.A. Venter Potchefstroom November 1979 My grateful thanks to: My promoter for painstaking and valued guidance The staff of the Ferdinand Postma Library f o r their invaluable cheerful assistance My typist , Rina Kahl My colleagues Rita Ribbens and Rita Buitendag My l ong-suffering husband and children My parents and parents-in-law for their constant encouragement CONTENTS 1 A SURVEY OF PINTER CRITICISM 1 1.1 Pinter's critical reputation: 1 bewildering variety of critical responses to his work 1.1.1 Reviews: 1958 2 1.1. 2 Reviews: 1978 3 1.1.3 Continuing ambiguity of response 4 Large number of critical \;,arks: 5 indicative of the amount of interest shown Clich~s and commonplaces in 6 Pinter criticism 1.2 Categories of Pinter criticism 7 1. 2.1 Criticism dealing with his dramatic 7 language 1. 2. 2 Criticism dealing with the obscurity 14 and opacity of his work 1. 2. 3 Criticism based on myth and ritual 18 1. 2 . 4 Criticism based on. his Jewishness 20 1. 2. 5 Pinter's work evaluated as realism 22 1.2. 6 Pinter's work evaluated as Drama of 24 ~ the Absurd 1.2. 7 The defective morality of his work 28 1.2 .8 Pinter and comedy: a preliminary 29 exploration to indicate the incom= plete nature of criticism on this aspect of his work 1,3 Statement o f intention: outline of 45 the main fields of inquiry in this study 1.4 Justification of the choice of plays 46 for analysis 2 WHY COMEDY? 4 7 2.1 The validity of making generi c 47 distinctions 2.2 Comedy as a vision of Zife 48 2.3 The continuing usefulness of genre 50 distinctions in literary criticism 2.4 NeopoZoniaZism 52 2.4.1 Tragicomedy 52 2.4.2 Dark comedy and savage comedy 54 2.4 . -

TIMES, BETRAYAL and a KIND of ALASKA PEREIRA, Luís Alberto

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-93132002000100005 MEMORY AS DISCOURSE IN HAROLD PINTER’S OLD LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude. Tristes Trópicos. Lisboa: Edições 70. 2004. TIMES, BETRAYAL AND A KIND OF ALASKA PEREIRA, Luís Alberto. Drama biográfico – “Hans Staden”. Coprodução luso-brasileira. 1999. Carla Ferreira de Castro RIBEIRO, Darcy. O Povo Brasileiro – a formação e o sentido do Brasil. São Universidade de Évora Portugal Paulo: Companhia das Letras. 2.ª Edição. 1995. [email protected] ROUCH, Jean. “Les Maîtres Fous”. Documentário/filme. 1955. Consultado a 15 de Maio de 2012: Abstract http://www.veoh.com/watch/v14179347tanDtaPa?h1=Jean+Rouch+%3 A+Les+ma%C3%AEtres+fous+-+The+mad+masters This paper aims at developing the topic of identity and the narration of SANTIAGO, Silviano. “Mário, Oswald e Carlos, intérpretes do Brasil”. ALCEU – v.5 – n.10 – Jan./Jun. 2005. P.p. 5 – 17. Consultado a 15 de Maio de the self through the other in Harold Pinter’s plays Old Times, Betrayal and A Kind . In these plays Pinter deploys strategies to convey multiple implications 2012: of Alaska which are based on the power of memory in which the structure of the plays is http://revistaalceu.com.puc-rio.br/media/alceu_n10_santiago.pdf concocted. STADEN, Hans. 1520-ca 1565. Viagem ao Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Academia Brasileira, 1930. 186 P. Consultado a 15 de Maio de 2012: http://purl.pt/151 Pinter, Language, Silence, Memory, Time STOLLER, Paul. “Artaud, rouch, and The cinema of Cruelty”. 1992. Key words: Visual Anthropology Review. Volume 8, n. º 2. “Every genuinely important step forward is accompanied by a return to the beginning...more precisely to a renewal of the beginning. -

THE COLLECTION, the LOVER and OLD TIMES Dr

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.4, No.3, pp.29-38, February 2016 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) HOME AS A BATTLEFIELD: POWER AND GENDER IN HAROLD PINTER'S THE COLLECTION, THE LOVER AND OLD TIMES Dr. Abdulaziz H. Alabdullah Assistant Professor, Kuwait University - Faculty of Arts - Department of English Language and Literature ABSTRACT: Harold Pinter has been hailed as a dramatist among the half-dozen best dramatists, able to use his considerable wit in unusual, resonant and riveting ways. The central theme of his work is one of the dominant themes of twentieth-century art: the struggle for meaning in a fragmented world. His characters are uncertain of whom or what they understand, in whom or what they believe, and who or what they are. Pinter’s characters operate by a stark ‘territorial imperative,' a primal drive for possession. In his plays, the struggle for power is an atavistic one between male and female. Hence sexuality as a means of power and control is our priority in discussing a select set of Pinter's playscripts. We here examine the element of sexuality in these chosen texts analysing the relationship between male and female characters, as they snipe and sling potshots across the most intimate of all battlefields: our home and castle. The texts are studied individually, in sequence, in an attempt to lay bare the technique and leverage of sexual negotiations in Pinter's work. KEYWORDS: Gender, Power, Sexuality, Relationships, Harold Pinter Introduction: Three plays by Harold Pinter, not perhaps his best known, The Collection, The Lover and Old Times, show how the playwright cruelly, but critically, investigates how sensible men have to get their rocks off, no matter what the social cost. -

From Pleasure to Menace: Noel Coward, Harold Pinter, and Critical Narratives

Fall 2009 41 From Pleasure to Menace: Noel Coward, Harold Pinter, and Critical Narratives Jackson F. Ayres For many, if not most, scholars of twentieth century British drama, the playwrights Noel Coward and Harold Pinter belong in entirely separate categories: Coward, a traditional, “drawing room dramatist,” and Pinter, an angry revolutionary redefining British theatre. In short, Coward is often used to describe what Pinter is not. Yet, this strict differentiation is curious when one considers how the two playwrights viewed each other’s work. Coward frequently praised Pinter, going so far as to christen him as his successor in the use of language on the British stage. Likewise, Pinter has publicly stated his admiration of Coward, even directing a 1976 production of Coward’s Blithe Spirit (1941). Still, regardless of their mutual respect, the placement of Coward and Pinter within a shared theatrical lineage is, at the very least, uncommon in the current critical status quo. Resistance may reside in their lack of overt similarities, but likely also in the seemingly impenetrable dividing line created by the premiere of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger on May 8, 1956. In his book, 1956 and All That (1999), Dan Rebellato convincingly argues that Osborne’s play created such a critical sensation that eventually “1956 becomes year zero, and time seems to flow both forward and backward from it,” giving the impression that “modern British theatre divides into two eras.”1 Coward contributed to this partially generational divide by frequently railing against so-called New Movement authors, particularly Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco, for being self-important and tedious. -

The Battle for Power Between the Dominant and the Subservient in the Dumb Waiter by Harold Pinter

Int. J. Eng.INTERNATIONAL Lang. Lit & Trans. Studies JOURNAL (ISSN:2349 OF ENGLISH-9451/2395 LANGUAGE,-2628) Vol.3.Issue. LITERATURE4.2016 (Oct.-Dec.) AND TRANSLATION STUDIES (IJELR) A QUARTERLY, INDEXED, REFEREED AND PEER REVIEWED OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.ijelr.in KY PUBLICATIONS RESEARCH ARTICLE Vol. 3. Issue.4.,2016 (Oct.-Dec. ) THE BATTLE FOR POWER BETWEEN THE DOMINANT AND THE SUBSERVIENT IN THE DUMB WAITER BY HAROLD PINTER Dr. ZEBA SIDDIQUI Assistant Professor, Amity School of Languages Amity University ABSTRACT Harold Pinter, the Nobel Prize Laureate is famous for his portrayal of the helplessness of the modern man, fighting a losing battle with a cruel and incomprehensible life, feeling the inevitability of decay and dejection. His plays brilliantly portray the modern human condition in which the meaning is no longer clear and is lost in the haze of scientific ambiguities and lost certainties. This paper Dr. ZEBA makes an attempt to present the view that higher power destroys the individual’s SIDDIQUI identity. Keywords: Harold Pinter, political drama, one-act play, Pinteresque . ©KY PUBLICATIONS The Dumb Waiter was written in 1957 and was highly received by the critics. In the 21st century with religion losing more ground than ever before and familiar narratives of certainties lost, with science and its ‘doubt culture’ making serious inroads in the modern mind and techno-brimming life, the work of Pinter is even more important than before. The Dumb Waiter is a representative of this condition of modern man and in many senses is even more important than ‘Waiting for the Godot’ by Samuel Beckett. -

The Dumb Waiter

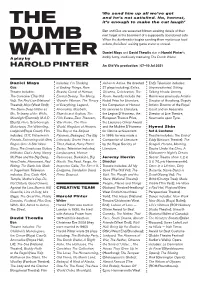

‘We send him up all we’ve got and he’s not satisfied. No, honest, THE it’s enough to make the cat laugh’ Ben and Gus are seasoned hitmen awaiting details of their next target in the basement of a supposedly abandoned cafe. DUMB When the dumbwaiter begins sending them mysterious food orders, the killers’ waiting game starts to unravel. Daniel Mays and David Thewlis star in Harold Pinter’s WAITER darkly funny, insidiously menacing The Dumb Waiter. A play by HAROLD PINTER An Old Vic production | 07–10 Jul 2021 Daniel Mays includes: I’m Thinking Ashes to Ashes. He directed End). Television includes: Gus of Ending Things, Rare 27 plays including: Exiles, Unprecedented, Sitting, Theatre includes: Beasts, Guest of Honour, Oleanna, Celebration, The Talking Heads. Jeremy The Caretaker (The Old Eternal Beauty, The Mercy, Room. Awards include the Herrin was previously Artistic Vic); The Red Lion (National Wonder Woman, The Theory Nobel Prize for Literature, Director of Headlong, Deputy Theatre); Mojo (West End); of Everything, Legend, the Companion of Honour Artistic Director of the Royal The Same Deep Water as Anomalisa, Macbeth, for services to Literature, Court and an Associate Me, Trelawny of the Wells, Stonehearst Asylum, The the Legion D’Honneur, the Director at Live Theatre, Moonlight (Donmar); M.A.D Fifth Estate, Zero Theorem, European Theatre Prize, Newcastle upon Tyne. (Bush); Hero, Scarborough, War Horse, The New the Laurence Olivier Award Motortown, The Winterling, World, Kingdom of Heaven, and the Molière D’Honneur Hyemi Shin Ladybird (Royal Court). Film The Boy in the Striped for lifetime achievement. -

Other Places and the Caretaker: an Exploration of the Inner Reality in Harold Pinter‘S Plays

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 581-588, April 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.4.581-588 Other Places and The Caretaker: An Exploration of the Inner Reality in Harold Pinter‘s Plays Hongwei Chen School of Foreign Studies, Beijing University of Science and Technology, Beijing, China Abstract—Exploring in his plays an overlapping area where social forces and human instincts interplay and superimpose upon each other, Harold Pinter dramatizes the inner reality of the characters who are trapped in various ambivalent forces, which collide and conflict, thereby producing the paradoxical tension in the subject’s instinct of escape and impulse to stay within. Index Terms—man in modern society, the realm of “the real”, other places, inner reality I. INTRODUCTION If we examine Harold Pinter‘s plays from The Room (1957) to Moonlight (1993), we may find that, however diversified the themes may appear (politics, family, or gender), two narrative models always can be found in them. In the first model, an individual escapes from various forms of ―rooms‖ (either a mysterious club, or family, or the Establishment) and is hounded, seized, interrogated and tortured for his attempt to be a non-conformist. Such characters as Stanley in The Birthday Party (1958), the son in Family Voices (1982), Victor in One for the Road (1984), as well as Fred and Jake in Moonlight, all belong to this category. In the second type of structure, characters are presented within various rooms, to which the characters cling as their territories. -

Lebanese American University Political Tension and Existentialist

Lebanese American University Political Tension and Existentialist Angst in the Drama of Harold Pinter and ‛Isām Mahfūz By Joelle Roumani Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Comparative Literature School of Arts and Sciences May 2012 ii iii iv v vi Political Tension and Existentialist Angst in the Drama of Harold Pinter and ‛Isām Mahfūz Joelle Roumani Abstract This research presents a detailed comparative analysis between Harold Pinter’s The Dumb Waiter and ‘Isām Mahfūz’s The Dictator. It transcends linguistic, cultural and historical boundaries to explore the cross-resonance between these two plays and the sharp dramatic, political, and existential affiliations between their two playwrights. In a significant manner, both plays distinctively reveal Pinter and Mahfūz’s conscientious political stand against manipulation and totalitarianism. They represent the defeated and crushed victims of modern democratic systems as they expose the underlying hypocrisy and dinginess of their practices. Through theories of existentialism, especially Jean Paul Sartre’s main philosophical precepts of human freedom as a condemnation rather than a blessing and of man’s free choice as burdening, and Albert Camus’s notion of the absurdity of life and existence, this thesis argues that Both Sa‛dūn and Gus are afflicted with angst being the quintessential representatives of existential heroes who are heavily caught in the absurdity of existence and who tremendously suffer from the consequences of their free choices. Different theater productions and adaptations of the two plays are also fully examined to dwell on their enduring influence on and reception by viewers at different times and places as they deliver an undying comment on man’s inescapable sense of ennui and on the duplicity of modern politics. -

Women Characters in Printer's Play's

© 2020 JETIR February 2020, Volume 7, Issue 2 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Women Characters in Printer's Play's 1Gowsia Fayaz, 2Dr Chaitanya 1Research Scholar, 2Assistant Professor 1Department of English, 1Bhagwant University, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India. Abstract : This paper examines five female characters from the British dramatist Harold Pinter’s five works, putting them in the sense of depicting “ The Femine. ‘’Pinter female characters must be seen not only in the tradition of stereotypical portraying women, but also in the light of the patriarchal structures they face-male domination, male gaze and male bonding.The second chapter background to discuss female characters- reasons for doing so are provided and the idea of a woman is introduced as the other . This concept led to women being stereotyped and subsequently misrepresented in the fiction. The traditional wife/whore dichotomy is explored. The chapter also discuss the aspects of on –stage representation with reference of drama.The third chapter involves close reading of the plays by Pinter – the Homecoming, the Birthday party , Betrayal and old times. The position of female characters are discussed in relation to the structure of power which they attempt to abolish. The chapter argues that although they achieve it, success as such does not challenge the patriarchal system.The fourth chapter focuses on Pinter’s understanding of the Czech stage. This describes the past of the staging’s, with a particular focus on two productions that took place long before the political change and were seen as threat to the official regime. It also analyzes two contemporary Betrayal stages in Divadlov celetne focusing on the female roles in these productions. -

Pinter's Comedy of Menace

PINTER'S COMEDY OF MENACE DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF IN ENGLISH BY MANJULA PIPLANI Under the Supervision ot PROF. ZAHIDA ZAIDI DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) June 1988 DS1360 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY AND ALIGARH-202001 MODERN EUROPEAN LANGL \GES June 4, 1988 Certified that Ms, Manjula Piplaal has cc»Rpleted her dissertation under m^ supervislcm. To t}» best of my lcno%d:edge this is her own work, a^ it is suitable for subnlssion in suppllc^ttion of M.Phil degree* N ^Vv^ u Prc^essor Zahlda Zaidl (Supervisor) ACKHOHLEDGMENT X feel privileged in expressing ny deep gratitude to my supervisor Prof. ZaMda Zaidl, Department of English, Allgarh Nuilim Ukiiversity* Aligarh for her invaftuable guidance and constant encouragementmin the completion of ray work • With her extensive Icnowledge and deep involvmnent in modem drama she helped me to overcome ny own shortcomings, and complete this project within a short time* Without her constant care and guidance my dissertation wouitd not have taken its present shape. Z am also deeply grateful to Dr. Munir Ahnad, Chairmflm, Department of English and Librarian,Maulana Azad Library, A.M.U., Aligarh for the departmental and library facilities that Z have injoyed for the compilation of my work. MARJULA PZPLANI CONTENTS CHAPTER - I Introduction j Dark Comedy and comeay ot Menace ... 1-28 CHAPTER - II The Room and The Dumb Walter ... 29-41 CHAPTER > ni The Birthday party and The Caretaker 42 - 57 The Homecoroinq and A Slight Ache ... 58-72 CCNCLUSICN ... ... 73-78 BIBLICX3RAPHY ... ... 79-85 ••»**• «*•*«* ffHAPT^Sgl INTRCDUCTICN t DARK CXDMEDY VWD COMEDY OF Mm ACE 1. -

The Development of Harold Pinter's Political Drama

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the pennission of the Author. FROM MENACE TO TORTURE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF HAROLD PINTER'S POLITICAL DRAMA A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English at Massey University Betty s. Livingston 1993 ii ABSTRACT There is a degree of continuity between Pinter's "comedies of menace" and his overtly political plays. The chief difference between the two types of plays is one of focus: in the "comedies of menace" Pinter emphasises social pressures exerted on the nonconforming indi victual, whereas in the overtly political plays he focusses explicitly on State oppression of the dissident. Pinter's passionate concern with politics has adversely affected his art, though there are signs of a return to form in his latest play, Party Time. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am extremely grateful to Professor Dick Corballis for his generous and invaluable guidance and assistance. CONTENTS Page Acknowledgement iii CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 CHAPTER TWO: Society versus the nonconforming 5 individual: the "comedies of menace" CHAPTER THREE: The State versus the dissident 48 individual: the overtly political plays CHAPTER FOUR: The effect of Pinter's political 82 commitment on his art NOTES 89 BIBLIOGRAPHY 97 CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Pinter's seemingly abrupt switch to explicitly political drama in One for the Road took many of his critics by surprise. -

Harold Pinter, Old Times

Harold Pinter, Old Times First produced by Royal Shakespeare Company at the Aldwych Theatre, London, 1 June 1971" ! Deeley - Colin Blakely" Anna - Vivien Merchant" Kate - Dorothy Tutin ! Directed by Peter Hall! ! “The desire for verification on the part of all of us, with regard to our own experience and the experience of others, is understandable but cannot always be satisfied. I suggest there can be no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false. A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false.”! ! (H. Pinter, “Introduction”, in Plays, 1996, p. xi).! Old Times, 1971! Dorothy Tutin, ! Colin Bateman ! and Vivien Merchant! 2013 - Harold Pinter Theatre, London! Directed by Ian Rickson, starring Rufus Sewell, Kristin Scott Thomas and Lia Williams! 1! 2! Old Times Shakespeare Theatre, Washington DC! May–July 2011! ! Deeley: Steven Culp! Kate: Tracy Lynn Middendorf! Anna: Holly Twyford" ! Directed by Michael Kahn!! ! The set of the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production of Old Times, directed by Michael Kahn. ! 1! 2! Michael Kahn, artistic director of the Shakespeare Theatre Company, Washington, DC, talks about Pinter’s Old Times.! [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJq2Nud1CL8]! ! ***! ! Old Times – PRESENTATION! [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tujShqEy5jY]! ! Harold PINTER, Old Times, New York, Grove, 1971, pp. 31–32.! [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nnNbKktTNSU]! ! Harold PINTER, Old Times, New York, Grove, 1971, pp. 34–35.! [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ymVtl2_Pa5E]! ! Harold PINTER, Old Times, New York, Grove, 1971, pp. 38–46.! [http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyXW3e-WI5Y]! ! Harold PINTER, Old Times, New York, Grove, 1971, pp.