In Spite of History? New Leftism in Britain 1956 - 1979

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Could There Be a Corbyn in Australia?

The emancipation of the working class must be the act of the working class itself ISSN 1446-0165 No.67. July 2017 http://australia.workersliberty.org How could there be a Corbyn in Australia? Could there be a political leader who could achieve Corbyn was mostly seen as not particularly leadership success at galvanising a mass movement for the working material. He was reluctant to stand, and thought he class, against capital, as Corbyn has done in Britain? We probably wouldn't get enough nominations. Having run as start by looking at how Corbyn became Labour leader. a flying the flag exercise, he had leadership thrust upon him. The 2008 slump hit Britain much harder than it hit Australia, so there has been more leftish agitation in Britain than Australia in the last 8 years, more sizeable left demonstrations, meetings, campaigns. This created a constituency in Labour Party politics in which the local party organisations swung a little to the left. So one of the preconditions for Corbyn, was the almost invisible revival of some Labour left, and some hope of Labour moving left under Ed Milliband. Ed Milliband as a very soft left leader was an electoral failure. This opened the way for a more serious left challenge to be welcomed by members, in the context of the impact of economic crisis in Britain. Milliband raised expectations, continuing to say leftish things from time to time, so he simultaneously raised hopes and yet disappointed them. After Ed Milliband resigned, all the contenders to replace him competed as to who could be most right wing because they thought that was the way to win. -

Peter Scott: Publications

Peter Scott: Publications 1. Books Peter Scott, Strategies for Postsecondary Education, London: Croom Helm,1975 Peter Scott, The Crisis of the University, London: Croom Helm, 1984 Peter Scott, Knowledge and Nation, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990 Michael Gibbons, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott and Martin Trow, The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies, London: Sage 1994 [Japanese translation, Maruzen, Tokyo 1997; Spanish translation, Ediciones Pomares-Corredor, Barcelona 1997] Peter Scott, The Meanings of Mass Higher Education, Buckingham: Open University Press,1995 Catherine Bargh, Peter Scott and David Smith, Governing Universities: Changing the Culture? Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996 Peter Scott (ed.), The Globalization of Higher Education, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1998 [Chinese translation, McGraw-Hill Education (Asia) / Peking University Press, 2012) Peter Scott (ed.) Higher Education Re-formed, London: Falmer Press, 2000 Catherine Bargh, Jean Bocock, Peter Scott and David Smith University Leadership: The Role of the Chief Executive, Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000 Helga Nowotny, Peter Scott and Michael Gibbons Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainity, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001 [Repenser la Science; savoir et société à l’ère de l’incertitude, Paris: Éditions Belin, 2003; Wissenschaft neu denken: Wissen und Öffentlichkeit in eineam Zeitalter Ungewißheit, Velbrück Wissenschaft 2004; Chinese translation, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press, 2012] Lars Engwall and Peter Scott (eds.) Trust in Universities, Wenner-Gren Volume 86, London: Portland Press, 2013 Claire Callender and Peter Scott (eds.) Browne and Beyond: Modernizing English Higher Education, London: Institute of Education Press (Bedford Way Papers), 2013 1 2. -

Radical Ambitions for Left-Wing Social Change and the Widespread Public Relevance of Sociology Remain Unfulfilled

Chapter 6 Worldly Ambitions The Emergence of a Global New Left For American left student activists of the early 1960s aiming to prac- tice their own politics of truth, Mills’s “Letter to the New Left” of 1960 provided inspiration. Attacking the liberal notion of an “end of ideology,” Mills suggested that radical ideals could once again affect the course of history by stirring the masses out of their apathy. Defending “utopian” thinking, he showed the necessity of a New Left that would break through the limits of the cold war consensus politics of the 1950s. Most important, Mills proclaimed to the emerging white student movement that “new generations of intellectuals” could be “real live agencies of social change.”1 To readers who already revered Mills for his trenchant social analysis, “Letter to the New Left” legiti- mated the notion that relatively privileged university students could be pivotal agents of social transformation. Shortly after its publication, Mills’s “Letter” was reprinted in the foremost intellectual journal of the American New Left, Studies on the Left. It was also published in pamphlet form by its most prominent organization, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), whose 1962 manifesto “The Port Huron Statement” heralded a New Left social movement of those “bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in the universities, looking uncom- fortably to the world we inherit.”2 Though “Letter to the New Left” is best known for its influence on the American student movement, Mills conceived of the New Left in international terms. In fact, his “Letter” was originally published in the 179 UC-Geary-1stpages.indd 179 10/8/2008 2:20:59 PM 180 Worldly Ambitions British journal New Left Review. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

Download (7Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/110901 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE COPYRIGHT Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. REPRODUCTION QUALITY NOTICE The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction, some pages which contain small or poor printing may not reproduce well. Previously copyrighted material (journal articles, published texts etc.) is not reproduced. THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED Between Identity and Practice: The Narratives of the Intellectual in the Twentieth-Century by Stephen Palmer BA, MSc A Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in the University of Warwick. Institute of Education -

OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor

University of Wollongong Research Online OZ magazine, London Historical & Cultural Collections 12-1968 OZ 17 Richard Neville Editor Follow this and additional works at: http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon Recommended Citation Neville, Richard, (1968), OZ 17, OZ Publications Ink Limited, London, 48p. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ozlondon/17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] OZ 17 Description Editor: Richard Neville. Design: Jon Goodchild. Writers: Andrew Fisher, Ray Durgnat, David Widgery, Angelo Quattrocchi, Ian Stocks. Artists: Martin Sharp, John Hurford, Phillipe von Mora. Photography: Keith Morris Advertising: Felix Dennis, REN 1330. Typesetting: Jacky Ephgrave, courtesy Thom Keyes. Pushers: Louise Ferrier, Felix Dennis, Anou. This issue produced by Andrew Fisher. Content: Louise Ferrier colour back issue/subscription page. Anti-war montage. ‘Counter-Authority’ by Peter Buckman. ‘The alH f Remarkable Question’ - Incredible String Band lyric and 2p illustration by Johnny Hurford. Martin Sharp graphics. Flypower. Poverty Cooking by Felix and Anson. ‘The eY ar of the Frog’ by Jule Sachon. ‘Guru to the World’ - John Wilcock in India. ‘We do everything for them…’ - Rupert Anderson on homelessness. Dr Hipocrates (including ‘inflation’ letter featured in Playpower). Homosexuality & the law. David Ramsay Steele on the abolition of Money. ‘Over and Under’ by David Widgery – meditations on cultural politics and Jeff uttN all’s Bomb Culture. A Black bill of rights – LONG LIVE THE EAGLES! ‘Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Mall’ - the ethos of the ICA. Graphic from Nottingham University. Greek Gaols. Ads for Time Out and John & Yoko’s Two Virgins. -

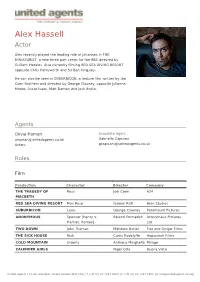

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

Debating Power and Revolution in Anarchism, Black Flame and Historical Marxism 1

Detailed reply to International Socialism: debating power and revolution in anarchism, Black Flame and 1 historical Marxism 7 April 2011 Source: http://lucienvanderwalt.blogspot.com/2011/02/anarchism-black-flame-marxism-and- ist.html Lucien van der Walt, Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, [email protected] **This paper substantially expands arguments I published as “Counterpower, Participatory Democracy, Revolutionary Defence: debating Black Flame, revolutionary anarchism and historical Marxism,” International Socialism: a quarterly journal of socialist theory, no. 130, pp. 193-207. http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=729&issue=130 The growth of a significant anarchist and syndicalist2 presence in unions, in the larger anti-capitalist milieu, and in semi-industrial countries, has increasingly drawn the attention of the Marxist press. International Socialism carried several interesting pieces on the subject in 2010: Paul Blackledge’s “Marxism and Anarchism” (issue 125), Ian Birchall’s “Another Side of Anarchism” (issue 127), and Leo Zeilig’s review of Michael Schmidt and my book Black Flame: the revolutionary class politics of anarchism and syndicalism (also issue 127).3 In Black Flame, besides 1 I would like to thank Shawn Hattingh, Ian Bekker, Iain McKay and Wayne Price for feedback on an earlier draft. 2 I use the term “syndicalist” in its correct (as opposed to its pejorative) sense to refer to the revolutionary trade unionism that seeks to combine daily struggles with a revolutionary project i.e., in which unions are to play a decisive role in the overthrow of capitalism and the state by organizing the seizure and self-management of the means of production. -

Catalogue 1949-1987

Penguin Specials 1949-1987 for his political activities and first became M.P. for West Fife in 1935. S156-S383 Penguin Specials. Before the war, when books could be produced quickly, we used to publish S156 1949 The case for Communism. volumes of topical interest as Penguin Specials. William Gallacher We are now able to resume this policy of Specially written for and first published in stimulating public interest in current problems Penguin Books February 1949 and controversies, and from time to time we pp. [vi], [7], 8-208. Inside front cover: About this shall issue books which, like this one, state the Book. Inside rear cover: note about Penguin case for some contemporary point of view. Other Specials [see below] volumes pleading a special cause or advocating a Printers: The Philips Park Press, C.Nicholls and particular solution of political, social and Co. Ltd, London, Manchester, Reading religious dilemmas will appear at intervals in this Price: 1/6d. new series of post-war Penguin Specials ... Front cover: New Series Number One. ... As publishers we have no politics. Some time ago S157 1949 I choose peace. K. Zilliacus we invited a Labour M.P. and a Conservative Specially written for and first published in M.P. to affirm the faith and policy of the two Penguin Books October 1949 principal parties and they did so in two books - pp. [x], [11], 12-509, [510] blank + [2]pp. ‘Labour Marches On’, by John Parker M.P., and adverts. for Penguin Books. Inside front cover ‘The Case for Conservatism’, by Quintin Hogg, [About this Book]. -

25 Years of Eastenders – but Who Is the Best Loved Character? Submitted By: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010

25 years of Eastenders – but who is the best loved character? Submitted by: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Wednesday, 17 February 2010 More than 2,300 members of the public were asked to vote for the Eastenders character they’d most like to share a takeaway with – with Alfie Moon, played by actor Shane Ritchie, topping the list of most loved characters. Janine Butcher is the most hated character from the last 25 years, with three quarters of the public admitting they disliked her. Friday marks the 25th anniversary of popular British soap Eastenders, with a half hour live special episode. To commemorate the occasion, the UK’s leading takeaway website www.Just-Eat.co.uk (http://www.just-eat.co.uk) asked 2,310 members of the public to list the character they’d most like to ‘have a takeaway with’, in the style of the age old ‘who would you invite to a dinner party’ question. When asked the multi-answer question, “Which Eastenders characters from the last 25 years would you most like to share a takeaway meal with?’, Shane Richie’s Alfie Moon, who first appeared in 2002 topped the poll with 42% of votes. The study was entirely hypothetical, and as such included characters which may no longer be alive. Wellard, primarily owned by Robbie Jackson and Gus Smith was introduced to the show in 1994, and ranked as the 5th most popular character to share a takeaway with. 1.Alfie Moon – 42% 2.Kat Slater – 36% 3.Nigel Bates – 34% 4.Grant Mitchell – 33% 5.Wellard the Dog – 30% 6.Peggy Mitchell – 29% 7.Arthur Fowler – 26% 8.Dot Cotton – 25% 9.Ethyl Skinner – 22% 10.Pat Butcher – 20% The poll also asked respondents to list the characters they loved to hate, with Janine Butcher, who has been portrayed by Rebecca Michael, Alexia Demetriou and most recently Charlie Brooks topping the list of the soaps most hated, with nearly three quarters of the public saying listing her as their least favourite character. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Blue Remembered Hills by Dennis Potter Directed by Jamesine Livingstone

Skipton Little Theatre Skipton Players’ Present Blue Remembered Hills By Dennis Potter Directed By Jamesine Livingstone Tuesday 20th to Saturday 24th April 2010 Director’s notes From the Chairman Dennis Potter was born in 1935 in Gloucestershire. After National Service he won a place at New College, Oxford where he read Philosophy, Politics and Economics. Hello and welcome to our penultimate play of He became one of Britain’s most accomplished and acclaimed dramatists. His plays for television include this our anniversary season, celebrating 50 Blue Remembered Hills (1979), Brimstone and Treacle years of dramatic art at the Little Theatre. (commissioned in 1975 but banned until 1987), the series Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), Blackeyes (1989) and Lipstick on Your Collar (1993). He also wrote novels, stage plays and screenplays. He died Next month on Saturday May 15th here We are always wanting to invite anyone Dennis Potter in June 1994. in the Little Theatre we are putting on who would like to help in any of our Some television drama ages badly: even the most revered classics creak a bit when watched again a fond remembrance in the form of an productions in any capacity whatever (no in the cold, contemporary, high-definition light of day. This does not apply to Dennis Potter’s 1979 television film Blue Remembered Hills. It was part of the ‘Play For Today’ strand, and it originally evening of “Nosh and Neuralgia”, sorry experience necessary!) from helping on lasted an hour and a quarter. Being Potter it looks without romanticism and with an analytical eye that should be “Nosh and Nostalgia” the door, selling refreshments, backstage at the long summer days of childhood during the war.