The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plays and Pinot: Bedroom Farce

Plays and Pinot: Bedroom Farce Synopsis Trevor and Susannah, whose marriage is on the rocks, inflict their miseries on their nearest and dearest: three couples whose own relationships are tenuous at best. Taking place sequentially in the three beleaguered couples’ bedrooms during one endless Saturday night of co-dependence and dysfunction, beds, tempers, and domestic order are ruffled, leading all the players to a hilariously touching epiphany. About the Playwright Alan Ayckbourn, in full Sir Alan Ayckbourn, (born April 12, 1939, London, England), is a successful and prolific British playwright, whose works—mostly farces and comedies—deal with marital and class conflicts and point out the fears and weaknesses of the English lower-middle class. He wrote more than 80 plays and other entertainments, most of which were first staged at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough, Yorkshire, England. At age 15 Ayckbourn acted in school productions of William Shakespeare, and he began his professional acting career with the Stephen Joseph Company in Scarborough. When Ayckbourn wanted better roles to play, Joseph told him to write a part for himself in a play that the company would mount if it had merit. Ayckbourn produced his earliest plays in 1959–61 under the pseudonym Roland Allen. His plays—many of which were performed years before they were published—included Relatively Speaking (1968), Mixed Doubles: An Entertainment on Marriage (1970), How the Other Half Loves (1971), the trilogy The Norman Conquests (1973), Absurd Person Singular (1974), Intimate Exchanges (1985), Mr. A’s Amazing Maze Plays (1989), Body Language (1990), Invisible Friends (1991), Communicating Doors (1995), Comic Potential (1999), The Boy Who Fell into a Book (2000), and the trilogy Damsels in Distress (2002). -

Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art

Studies in 20th Century Literature Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 6 6-1-2001 (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Robert Neustadt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the American Literature Commons, Latin American Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Neustadt, Robert (2001) "(Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art ," Studies in 20th Century Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 2, Article 6. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.1510 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Ef)Facing the Face of Nationalism: Wrestling Masks in Chicano and Mexican Performance Art Abstract Masks serve as particularly effective props in contemporary Mexican and Chicano performance art because of a number of deeply rooted traditions in Mexican culture. This essay explores the mask as code of honor in Mexican culture, and foregrounds the manner in which a number of contemporary Mexican and Chicano artists and performers strategically employ wrestling masks to (ef)face the mask- like image of Mexican or U.S. nationalism. I apply the label "performance artist" broadly, to include musicians and political figures that integrate an exaggerated sense of theatricality into their performances. -

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

The Best According To

Books | The best according to... http://books.guardian.co.uk/print/0,,32972479299819,00.html The best according to... Interviews by Stephen Moss Friday February 23, 2007 Guardian Andrew Motion Poet laureate Choosing the greatest living writer is a harmless parlour game, but it might prove more than that if it provokes people into reading whoever gets the call. What makes a great writer? Philosophical depth, quality of writing, range, ability to move between registers, and the power to influence other writers and the age in which we live. Amis is a wonderful writer and incredibly influential. Whatever people feel about his work, they must surely be impressed by its ambition and concentration. But in terms of calling him a "great" writer, let's look again in 20 years. It would be invidious for me to choose one name, but Harold Pinter, VS Naipaul, Doris Lessing, Michael Longley, John Berger and Tom Stoppard would all be in the frame. AS Byatt Novelist Greatness lies in either (or both) saying something that nobody has said before, or saying it in a way that no one has said it. You need to be able to do something with the English language that no one else does. A great writer tells you something that appears to you to be new, but then you realise that you always knew it. Great writing should make you rethink the world, not reflect current reality. Amis writes wonderful sentences, but he writes too many wonderful sentences one after another. I met a taxi driver the other day who thought that. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Making Pictures the Pinter Screenplays

Joanne Klein Making Pictures The Pinter Screenplays MAKING PICTURES The Pinter Screenplays by Joanne Klein Making Pictures: The Pinter Screenplays Ohio State University Press: Columbus Extracts from F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Last Tycoon. Copyright 1941 Charles Scribner's Sons; copyright renewed. Reprinted with the permission of Charles Scribner's Sons. Extracts from John Fowles, The French Lieutenant's Woman. Copyright © 1969 by John Fowles. By permission of Little, Brown and Company. Extracts from Harold Pinter, The French Lieutenant's Woman: A Screenplay. Copyright © 1982 by United Artists Corporation and Copyright © 1982 by J. R. Fowles, Ltd. Extracts from L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between. Copyright © 1954 and 1981 by L. P. Hartley. Reprinted with permission of Stein and Day Publishers. Extracts from Penelope Mortimer, The Pumpkin Eater. © 1963 by Penelope Mortimer. Reprinted by permission of the Harold Matson Company, Inc. Extracts from Nicholas Mosley, Accident. Copyright © 1965 by Nicholas Mosley. Reprinted by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. Copyright © 1985 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Klein, Joanne, 1949 Making pictures. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Pinter, Harold, 1930- —Moving-picture plays. I. Title. PR6066.I53Z713 1985 822'.914 85-326 Cloth: ISBN 0-8142-0378-7 Paper: ISBN 0-8142-0400-7 for William I. Oliver Contents Acknowledgments ix Chronology of Pinter's Writing for Stage and Screen xi 1. Media 1 2. The Servant 9 3. The Pumpkin Eater 27 4. The Quiller Memorandum 42 5. Accident 50 6. The Go-Between 77 1. The Proust Screenplay 103 8. -

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

PROSCENIUM Waiting For Godot By Samuel Beckett Waiting For Godot For Waiting Wednesday 16th January to Saturday 19th January 2008 Compass Theatre, Ickenham PROSCENIUM Waiting For Godot By Samuel Beckett Waiting For Godot For Waiting Wednesday 16th January to Saturday 19th January 2008 Compass Theatre, Ickenham WAITING FOR GODOT The Author 1906 Born on Good Friday, April 13th, at Foxrock, near Dublin, son of a quantity surveyor. Both parents were Protestants. BY SAMUEL BECKETT 1920-3 Educated at Portora Royal School, Ulster. 1923-7 Trinity College, Dublin. In BA examinations placed first in first class in Modern Literature (French and Italian). Summer 1926: first contact with France, a bicycle tour of the chateaux of the Loire. 1927-8 Taught for two terms at Campbell College, Belfast. CAST: 1928-30 Exchange lecturer in Paris. Meets James Joyce. 1930 First separately published work, a poem Whoroscope. Four terms as assistant lecturer in French, Trinity College, Dublin. Estragon.....................................................................................................Duncan Sykes Helped translate Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabella into French. 1931 Performance of first dramatic work, Le Kid, a parody sketch Vladimir ................................................................................................ Mark Sutherland after Corneille. Proust, his only major piece of literary criticism, Pozzo .............................................................................................................. Robert Ewen published. -

Harold Pinter's Transmedial Histories

Introduction: Harold Pinter’s transmedial histories Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Bignell, J. and Davies, W. (2020) Introduction: Harold Pinter’s transmedial histories. Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, 40. pp. 481-498. ISSN 1465-3451 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1778314 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/89961/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1778314 Publisher: Taylor & Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television ISSN: 0143-9685 (Print) 1465-3451 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/chjf20 Introduction: Harold Pinter’s Transmedial Histories Jonathan Bignell & William Davies To cite this article: Jonathan Bignell & William Davies (2020): Introduction: Harold Pinter’s Transmedial Histories, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1778314 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 18 Jun 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=chjf20 Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1778314 INTRODUCTION: HAROLD PINTER’S TRANSMEDIAL HISTORIES Jonathan Bignell and William Davies This article introduces the special issue by exploring the transmediality of Harold Pinter's work. -

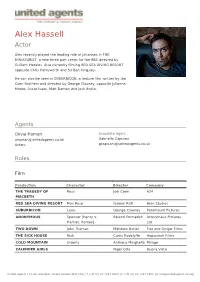

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A. -

The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter

Ben Ferber The Hothouse and Dynamic Equilibrium in the Works of Harold Pinter I have no doubt that history will recognize Harold Pinter as one of the most influential dramatists of all time, a perennial inspiration for the way we look at modern theater. If other playwrights use characters and plots to put life under a microscope for audiences, Pinter hands them a kaleidoscope and says, “Have at it.” He crafts multifaceted plays that speak to the depth of his reality and teases and threatens his audience with dangerous truths. In No Man’s Land, Pinter has Hirst attack Spooner, who may or may not be his old friend: “This is outrageous! Who are you? What are you doing in my house?”1 Hirst then launches into a monologue beginning: “I might even show you my photograph album. You might even see a face in it which might remind you of your own, of what you once were.”2 Pinter never fully resolves Spooner’s identity, but the mens’ actions towards each other are perfectly clear: with exacting language and wit, Pinter has constructed a magnificent struggle between the two for power and identity. In 1958, early in his career, Pinter wrote The Hothouse, an incredibly funny play based on a traumatic personal experience as a lab rat at London’s Maudsley Hospital, proudly founded as a modern psychiatric institution, rather than an asylum. The story of The Hothouse, set in a mental hospital of some sort, is centered around the death of one patient, “6457,” and the unexplained pregnancy of another, “6459.” Details around both incidents are very murky, but varying amounts of culpability for both seem to fall on the institution’s leader, Roote, and his second-in- command, Gibbs. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.